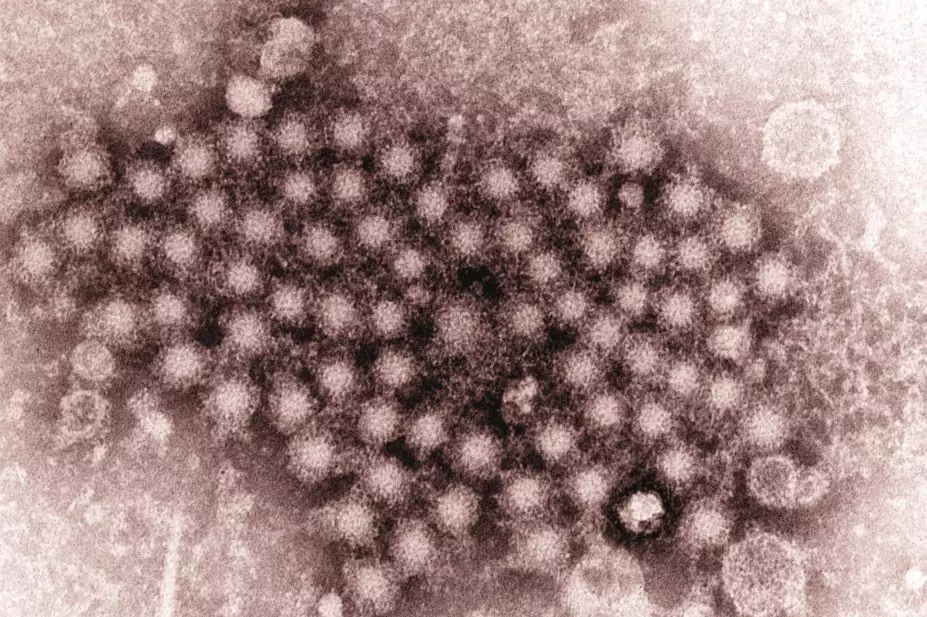

CDC / Joe Miller

Two new combination therapies that have the potential to cure patients with long-term hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and rule out the need for interferon are being recommended for approval across the EU.

The European Medicines Agency (EMA), which evaluates medicinal products for use in EU, is proposing that marketing authorisation is given to sofosbuvir/velpatasvir (Epclusa; Gilead Sciences) and grazoprevir/elbasvir (Zepatier; Merck Sharp & Dohme).

Both products are direct-acting antivirals, which block the action of proteins that are essential for viral replication. Treatment with them also means that patients do not need to take interferons, which are traditionally poorly tolerated and have serious side effects.

The sofosbuvir/velpatasvir combination targets the proteins NS5B and NS5A, as well as all six genotypes of HCV, while grazoprevir/elbasvir targets the proteins NS3/4A and NS5A and genotypes 1 and 4.

The recommendations follow the results of clinical trials involving patients whose hepatitis C status was tested 12 weeks after taking the combination therapies.

For patients taking sofosbuvir/velpatasvir, researchers found that HCV was no longer detected in the blood 12 weeks after the end of treatment, with or without ribavirin. More than 90% of patients across all genotypes had no detectable HCV in their blood at the end of the trial, and could be considered as ‘cured’ of the virus. The sustained virologic response rate for patients with genotype 3 was around 90%.

More than 90% of patients given grazoprevir/elbasvir had no detectable hepatitis C virus in their blood at 12 weeks. The therapy was particularly effective in patients with chronic kidney disease who usually have a poor prognosis.

The recommendations by the EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) will now go the European Commission for marketing authorisation to be approved.

Sofosbuvir is already available in the EU under the brand name Sovaldi, and as a combination therapy with ledipasvir (Harvoni).

“The major step forward is [sofosbuvir/velpatasvir], which means that there is now a good treatment for genotype 3 hepatitis C,” says Steve Ryder, a consultant physician in hepatology and gastroenterology at the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences at the University of Nottingham.

“Almost half of UK patients have this strain and it didn’t respond well to the previous generation of oral treatments… so this is very good news for a group of patients who currently still have to take interferon-based treatments.”

He says grazoprevir/elbasvir is a good combination for genotypes 1 and 4, but adds that there are already “very effective treatments for these genotypes so its main benefit is to potentially provide more choice and drive down the very high cost of these medicines”.

Ryder says the cost of the drugs will affect whether or not they will become available on the NHS.

“NHS England has placed great restrictions on access to Harvoni,” he says. “Many other nations have done much more intelligent deals with pharma that both protect the drug budget but give much better access to treatment than we have [in the UK] – Australia and Israel are good examples.”

The CHMP’s recommendations were welcomed by the charity Hepatitis C Trust. Its chief executive, Charles Gore, says: “More drugs mean more competition, which generally means lower prices. At the same time these drugs work for all genotypes so we should be able to consign the use of interferon to history, even for genotypes 2,3, 5 and 6, which will be a huge benefit and an enormous relief to people living with hepatitis C.”

In May 2016, the World Health Organization published the first ever global viral hepatitis strategy, which sets a worldwide target to eliminate viral hepatitis B and C by 2030. The strategy was unanimously supported by the 194 member states of the World Health Assembly at a meeting on 23–26 May 2016.

You may also be interested in

Antivirals have little effect on mortality in patients hospitalised with COVID-19, suggest WHO trial interim results

Government tightens availability of remdesivir treatment for COVID-19 patients as supplies shrink