Shutterstock.com

Patients who take glitazone drugs to manage their diabetes may have some protection from developing Parkinson’s disease, suggests research published in PLOS Medicine

[1]

on 21 July 2015.

Currently, there are no drugs available that can reduce the chance of developing the disease. But in a retrospective cohort study, researchers found a 28% lower rate of Parkinson’s in diabetic patients taking glitazones, compared with patients given other drugs to manage their diabetes.

Arthur Roach, director of research and development at the charity Parkinson’s UK, says much is already known about glitazone drugs’ effects on brain cells that are damaged in Parkinson’s. However, he hopes the results of this study will “spark further research into developing new drugs that work in a similar way to glitazone drugs, and have the ability to reduce someone’s chance of developing Parkinson’s”.

Roach adds that the results do not suggest healthy people should take glitazones, which can have severe side effects, to reduce their chance of developing Parkinson’s disease.

Researchers used the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink to retrospectively track diabetic patients taking glitazones from 1999 to 2013, to see if they had any impact on the likelihood of developing Parkinson’s disease.

The health records of 44,597 diabetic patients given glitazones were each matched to five other diabetics with similar characteristics who did not receive the medicines (n=120,373).

The researchers found that among patients exposed to glitazones, the incidence of Parkinson’s disease was 6.4 per 10,000 patient years compared with 8.8 per 10,000 patient years for those prescribed other antidiabetic treatments (incidence rate ratio [IRR] 0.72, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.60–0.87, P<0.001). However, when the results are broken down, current use of glitazones was associated with a strong protective effect (IRR 0.59, 95% CI 0.46–0.77, P<0.0001). Past use was not (IRR 0.85, 95% CI 0.65–1.10, P=0.209).

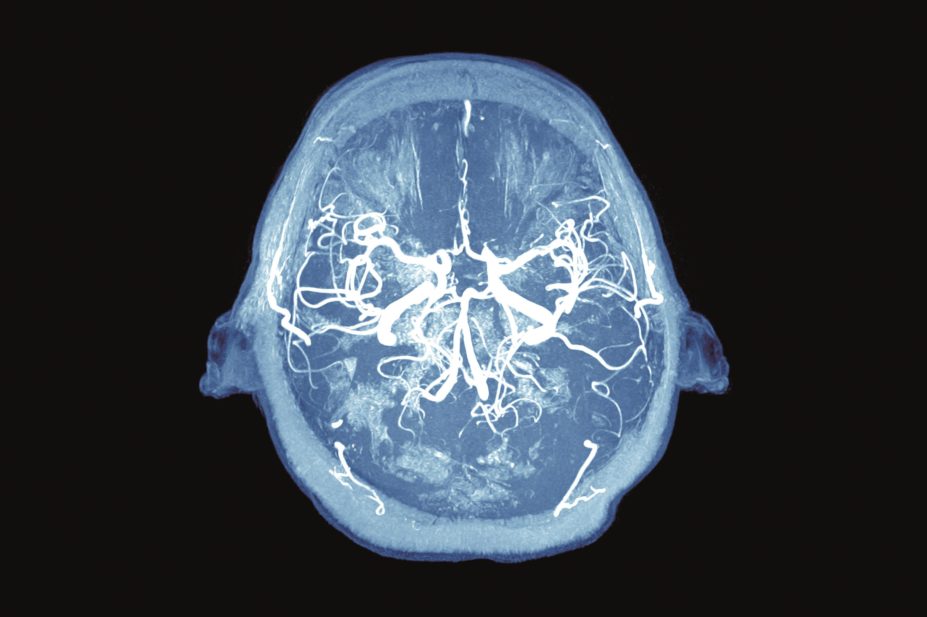

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive degenerative neurological condition, characterised by gradual loss of control of movement in the body. This is primarily caused by the death of dopamine-producing cells in the substantia nigra, a part of the brain involved in movement.

According to the results of in vitro and animal studies, peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor gamma (PPAR) agonist receptors, which include glitazones, may have neuroprotective effects. But Roach emphasises that this study only looked at people with diabetes, not healthy individuals.

Nonetheless, the researchers say they found “strong evidence” for a protective association between glitazone exposure and the incidence rate of Parkinson’s disease in humans — consistent with previous evidence from animal and in vitro studies. “Interventions based on the same mechanisms as PPARγ agonist activity may be fruitful targets for future research in Parkinson’s disease,” they conclude.