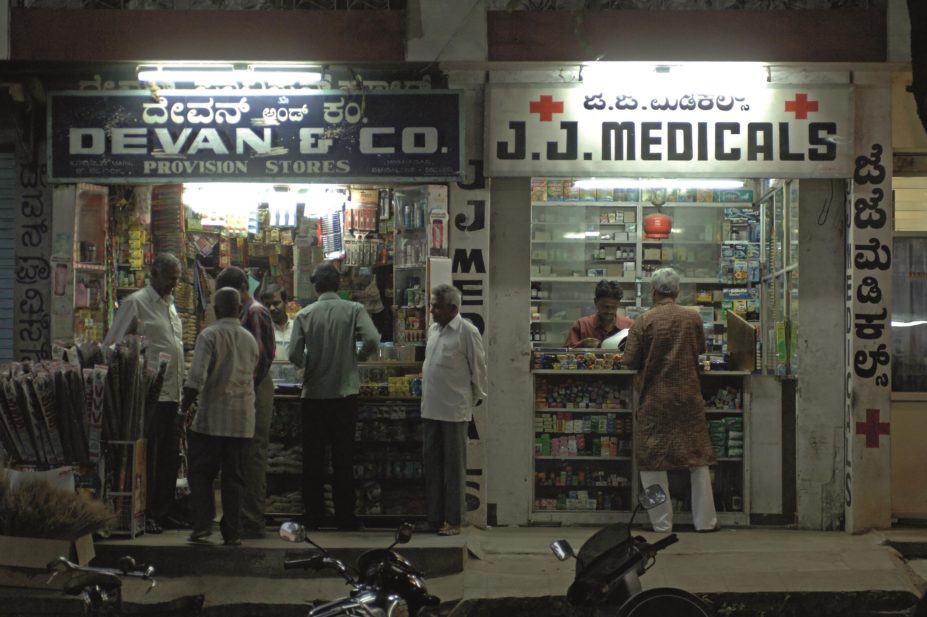

imageBROKER / Alamy Stock Photo

Medicines used to prevent cardiovascular disease are unavailable and unaffordable for the majority of patients living in low income countries, according to research published in The Lancet

[1]

on 21 October 2015.

However, in high income countries – where these drugs are available and affordable — around 35–50% of patients who have heart disease or history of a stroke do not receive them.

The findings boost the need for a radical rethink of the pricing of these medicines and how they are made available if the World Health Organization’s (WHO) 2025 global target for the prevention of recurrent cardiovascular disease (CVD) is to be met, the researchers say. The WHO wants these drugs to be available in 80% of communities worldwide and used by 50% of eligible patients in ten years’ time.

“In low income and middle income countries, patients with previous CVD were less likely to use all four medicines if fewer than four were available,” the researchers say. “In communities in which all four medicines were available, patients were less likely to use medicines if the household potentially could not afford them.”

Researchers considered whether four drug classes used in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease — namely, aspirin, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and statins — were available to patients in pharmacies in 18 high, middle and low income countries in rural and urban areas. Data were collected over ten years between 2003 and 2013.

They also set out to discover if the drugs were affordable, which was defined by whether the cost of all four was less than 20% of the household capacity to pay.

All four drug classes were available in 95% of urban communities and 90% of rural communities in high income countries, while in upper middle income countries the drugs were available in 80% of urban communities and 73% of rural communities.

Researchers found that in lower middle income countries the drugs’ availability was 62% in urban communities and 37% in rural communities. The lowest availability was found in low income countries – 25% in urban communities and 3% in rural communities.

India was analysed on its own, given its large generic pharmaceutical industry, and the researchers found that the four drug classes were available in 89% of urban communities and 81% of rural communities.

When researchers considered affordability, they found that the medicines were unaffordable for 60% of households in low income countries (excluding India); 33% of households in lower middle income countries; 25% of households in upper middle income countries; and under 1% of households in high income families. In India, the medicines were unaffordable in 59% of households.

When the four medicines are both available and affordable, only 18% of patients in high-income countries and 3% of patients in low income and middle income countries are using them. This suggests, they say, that factors beyond availability and affordability affect the use of these medicines, and should be explored.

“Both low availability and affordability are associated with low use of these medicines. Unless both availability and affordability of these medicines are improved, their use is likely to remain low in most of the world,” the researchers say.

Strong national CVD plans are essential to increase availability of CVD drugs, says Mario Ottiglio, director of public affairs, communications and global health policy at the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations.

“The real issue is whether countries are able to successfully implement universal healthcare systems that facilitate their populations being able to access these medicines,” he says.

“Countries could enhance capacity for generic substitution (many essential CVD medicines have been off-patent for years), improve their procurement practices, for example, by enhancing efficiency of procurement and preventing stock-outs, or addressing excessive mark-ups between procurement and patient prices, or exempting medicines from tariffs and taxes.”

“Sustainable access to quality pharmaceuticals goes beyond the pill,” he says.

Pharmaceutical companies already help improve access to CVD drugs through tiered pricing schemes and programmes addressing care delivery issues such as education, training and treatment guidelines, he adds.

In an accompanying comment piece, joint author Louis Niessen, a health economist at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, said the use of medicines is affected by many factors such as general awareness, health literacy, service quality, and the competence of health workers.

“Equating potential affordability of medicines with appropriate use at community level is too big a step. Appropriate and rational use of medicines is conditional to health improvements. However, increased availability of medicines might also lead to their misuse,” he said.

References

[1] Khatib R, McKee M, Shannon H et al. Availability and affordability of cardiovascular disease medicines and their effect on use in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries: an analysis of the PURE study data. The Lancet 2015. doi:10.1016/ S0140-6736(15)00469-9