Wellcome Images

Gathered in a small room in the East London offices of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS), members of the British Society for the History of Pharmacy and the RPS met for a lecture entitled: ‘The Forgotten Partner: Silas M Burroughs.’

Julia Sheppard, Burroughs’ biographer and former head of research and special collections at the Wellcome Library, painted an intriguing picture of a colourful personality whose untimely death left him hidden in the shadow of his partner, Henry Wellcome.

Sheppard began the story of Burroughs’ life with a personal account of her trip to visit his grave in Monte Carlo, Monaco. Despite all he achieved during his life, Burroughs received a meagre level of recognition after he died. The tombstone by his grave had fallen into disrepair and there were even plans to demolish it because it rarely attracted visitors. As a result, Sheppard and the Wellcome Trust organised for the tombstone to be cleaned and renovated in order to preserve his memory and its link with Henry Wellcome.

“History is unkind to forgotten personalities,” Sheppard told her audience and, as we were to find out, Burrough did not deserve to be forgotten.

Sheppard contends that the main reason for Burroughs’ diminished status was that he died at the relatively young age of 49 years, after which Henry Wellcome inherited his work. Their relationship was far from amicable towards the end and it can be assumed that Wellcome was not concerned with whether or not his former friend received the recognition he deserved.

Sheppard envisages Burroughs as a man of intense energy — a “steam engine” that helped to change the pharmaceutical industry forever

The rich orphan

Burroughs was born in 1846 in Medina, a small village in upstate New York. Burroughs idolised his father, a wealthy and influential politician. However, both his mother and father died before Burroughs reached the age of 12, leaving him hugely wealthy.

Burroughs started his career as a drug clerk and counter salesman for a pharmaceutical manufacturer and it was in this role that he started to develop key skills in sales and drug knowledge.

From her research, Sheppard envisages Burroughs as a man of “intense energy” – a “steam engine” that helped to change the pharmaceutical industry forever. Throughout his life he worked hard to keep ahead and was an expert in networking and promoting his new drugs internationally which, in the 19th century, was no mean feat, often involving uncomfortable and sometimes dangerous forms of transport.

During the American Civil War (1861–1865) demand for drugs was high, but many that were available were of poor quality and prepared by pestle and mortar. The introduction of compressed pills helped to drive up the standards and safety of medicines in America, although England remained behind the times.

In 1878, aged 32, Burroughs became the European agent for John Wyeth & Brother, a major pharmaceutical manufacturer in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, specialising in compressed medicine tablets. Burroughs realised that he might be able to make his fortune by importing the compressed pills and marketing them in England and Europe.

A unique business opportunity

During this time he had also started his own firm called S M Burroughs and Co. through which, unusually for that time, he sold medical supplies and nutritional supplements straight to doctors with no direct advertising to consumers. He was a generous man and was happy to give out free samples in order to promote his products. In this role, Burroughs visited Ireland, Paris and Germany and built up his status in the field. However, his growing business was too much to handle all alone and he need a partner to hold down the fort in London.

As a result, in September 1880, Burrough established Burroughs, Wellcome and Co. with his then best friend, Henry Wellcome. Burroughs funded the company, because Wellcome came from a poor background. But he did this happily, and sometimes funded his friend as well as the business.

As well as having a keen business mind, Sheppard also discovered that Burroughs was a strict Presbyterian, teetotaller and staunch liberalist. He frequently gave public speeches, fighting for free railway travel to lessen congestion, and free trade among other causes. Penny Bailey, a writer for the Wellcome Trust, said that if Burroughs had lived longer, he probably would have stood for parliament.

Shortly after Burroughs, Wellcome & Co. was formed, Burroughs set off on a worldwide tour, visiting India and Africa, among other places. Travelling internationally gave him valuable insight into the issues associated with storing drugs in hot climates and during this time he developed travel first aid kits and other related products. Burroughs’ warm personality and excellent networking ability meant that he was able to build up valuable contacts across the world.

Tabloid went on to become one of the most powerful brand names in business history

Developing the Tabloid brand

Because of the heavy stamp duty on pills imported from America, Burroughs and Wellcome decided to start manufacturing their own, which was a novel move for the time. At this point, Burroughs decided to make the break from his role at John Wyeth & Brother and spent £5,000 on a factory in Wandsworth. Their pills were an instant success and it wasn’t long before they needed to expand the factory. Subsequently, they purchased the Phoenix Paper Mills site at Dartford in Kent, where the company remained until the 1980s.

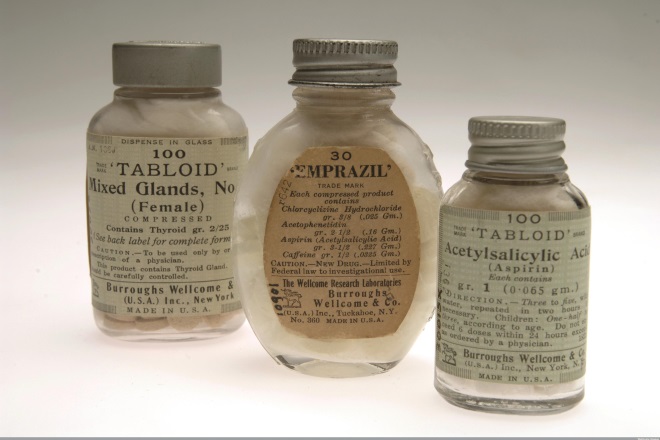

Because Burroughs, Wellcome & Co’s success led to a number of copycat products, the partners decided it was time for a brand name. By combining the words tablet and alkaloid, ‘Tabloid’ was born, which went on to become one of the most powerful brand names in business history. Sheppard also discovered that Burroughs and Wellcome had to instigate legal action several times to stop the brand being copied.

Source: Wellcome Images

By combining the words tablet and alkaloid, ‘Tabloid’ was born, which went on to become one of the most powerful brand names in business history. Pictured: Tabloid Mixed Glands No. 2 tablets, Emprazil tablets and Tabloid Acetylsalicylic Aid tablets (aspirin)

An unhappy partnership

The partners spent a lot of time and money to ensure that the company had a contented workforce, and introduced the eight-hour working day ahead of other companies. They also arranged extravagant annual outings and introduced staff bonuses. As a result, not a single strike occurred during the history of the company. The same contentment cannot be attributed to its owners, however.

Burroughs and Wellcome had hugely different personalities, which at first, were complementary to the business – Burroughs was charming and generous, while Wellcome was ambitious and much more cautious. However, Sheppard’s research led her to uncover small niggles between the partners eventually that became huge rows. These were often about money although some of the arguments were personal and involved Burroughs’ wife, Olive Chase. Wellcome thought that Burroughs didn’t take the business seriously, while Burroughs described Wellcome as a “snake”. Eventually the two partners only communicated through lawyers. As Sheppard described it, there was a “litany of discord”.

During this time, Burroughs contracted malaria on numerous occasions, as well as suffering from depression and exhaustion. Unable to keep up, he invited Wellcome to take charge of the company. But Wellcome declined; after all, he did not own a 50% share.

The men’s relationship was put under further pressure when Burroughs approached another friend to instigate a partnership without telling Wellcome. In 1884 Burroughs suggested a dissolution and looked to purchases in New York, but Wellcome refused. Despite the tensions, the firm remained successful.

The final conclusion

In 1894 Burroughs and Wellcome reached a complicated stalemate and renegotiations of their partnership were started. However, in February 1895 Burroughs developed pneumonia while in the South of France and died in a matter of days – much to the relief of Wellcome, Sheppard added — leaving behind Chase and their three young children. After a rigorous legal dispute between Wellcome and Chase, she came away with a large settlement and Wellcome gained full control of the company in 1898, which went on to expand globally.

After his sudden death, Burroughs’ role in the company was somewhat forgotten and Wellcome was credited with its success. Even the Royal Pharmaceutical Society scholarship in Burroughs’ name no longer exists.

Limited recognition of Burroughs’ achievements exist to this day – there is a plaque at Livingstone Cottage Hospital in Dartford and of course, his restored grave in Monte Carlo. However, as Sheppard’s biography will highlight in more detail, without his extraordinary gift as a salesman, financial backing, his encouragement of Wellcome to become a partner, his enthusiasm and willingness to take risks, there would have been no Burroughs, Wellcome and Co. and more than likely no Wellcome Trust.

- This article was amended on 22 March 2016 to correct an error. Instead of saying Dartford was in Essex, the article should have stated Dartford was in Kent.