ROYAL PHARMACEUTICAL SOCIETY MUSEUM

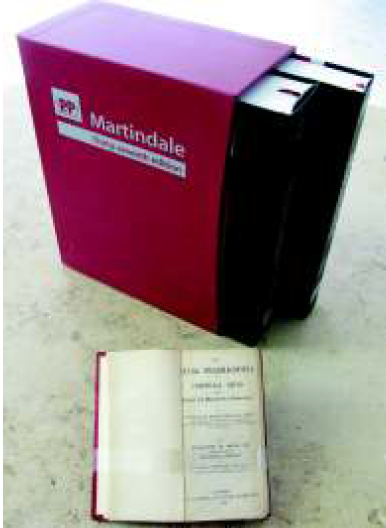

The publication now known worldwide as ‘Martindale: the complete drug reference’ was first published in July 1883. For 130 years it has constantly evolved, remaining an essential resource for pharmacists. Today, ‘Martindale’ provides healthcare professionals with unbiased evaluated information on drugs in clinical use worldwide, as well as herbal and complementary medicines, pharmaceutical excipients, toxic substances, disinfectants, and pesticides. At the last count, there are 49 chapters, approximately 6,000 drug monographs in the print version (over 7,000 online), nearly 700 drug treatment reviews, and over 240,000 preparations from nearly 25,000 drug manufacturers in 49 countries or regions.

The publication has the rare distinction of being known by the name of its original author, William Martindale. However, it was originally entitled ‘The extra pharmacopoeia’ and it was not until the 26th edition (1972) that it was published as ‘Martindale: the extra pharmacopoeia’ for the first time, having for years been increasingly known as ‘Martindale’. The 32nd edition (1999) saw another title change to ‘Martindale: the complete drug reference’ because the subtitle “The extra pharmacopoeia” was thought to have lost its relevance. Furthermore, comparisons to pharmacopoeias are misplaced.

The men and the book

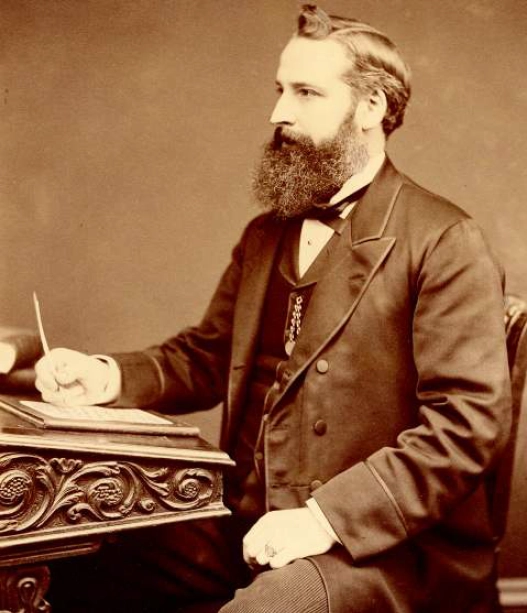

William Martindale (1840–1902) worked during a period of rapid scientific discovery. This had a direct impact on the development of pharmaceutical treatments. New medicinal substances and preparations were constantly being discovered and developed. Martindale himself was an inventor and developer of pharmaceutical formulations. From 1868 onwards he regularly published papers and also answered pharmacists’ questions in The Pharmaceutical Journal. Martindale saw the need for all this new information to be compiled in a book. ‘The extra pharmacopoeia’ was envisioned to fill this role. It enabled pharmacists to have access to up-to-date information about the latest pharmaceutical treatments. Martindale was assisted by W. Wynn Westcott, who compiled the medical references.

The first edition, entitled ‘The extra pharmacopoeia of unofficial drugs and chemical and pharmaceutical preparations’, was a slim pocket volume of 313 pages containing some 250 drug monographs. The “extra” in ‘The extra pharmacopoeia’ referred to the focus of early editions to describe drugs and substances not included in the British Pharmacopoeia (first published in 1864), which only listed well established, official preparations. Revised editions of the BP were only published every 12 to 18 years which, during a period of rapid pharmaceutical development, led some critics to claim that it was already outdated by the time of publication. In comparison, new editions of ‘The extra pharmacopoeia’ were published every one to three years during William Martindale’s lifetime. These were not complete revisions, unlike modern editions, but updates based on Martindale’s latest research. To make the book more comprehensive, the fourth edition in 1885 also included the official preparations of the BP.

In total, William Martindale produced 10 editions of ‘The extra pharmacopoeia’ from 1883 until his death in 1902. In addition to compiling new editions and owning a busy central London pharmacy, Martindale was actively involved in many other areas of pharmacy. In 1889, he was elected to the council of the Pharmaceutical Society, serving as its president from 1899 to 1900. he also worked on the BP in 1898. Martindale’s dedication to the profession of pharmacy led to overwork, which had a detrimental effect on his health. In February 1902, aged 61, he was found dead at home. In a note to his wife he complained that his exhausted brain did not allow him to grasp his work. While suffering from nervous depression, caused by serious overwork, he had taken prussic acid (hydrogen cyanide). A verdict of suicide was recorded at the inquest.

After William Martindale’s death, the production of ‘The extra pharmacopoeia’ and the ownership of the W. Martindale pharmaceutical business passed to his son, William harrison Martindale (1874–1933). W. H. Martindale qualified as a pharmacist in 1898 and also experimented on new compounds and formulations. This work was compiled in ‘The extra pharmacopoeia’, and new editions were published every two to three years. W. H. Martindale developed the book’s chemical and analytical content. however, by the 1920s, he started to suffer from heart trouble, exacerbated by overwork. In April 1933, aged only 58, he died of heart failure after a severe illness. his obituary in The Pharmaceutical Journal stated that his dedication to the book “. . . shortened his life, and was in large measure responsible for the initial breakdown in health”.

In his final edition’s preface (20th edition, Vol I; 1932), W. H. Martindale wrote of his aims for ‘The extra pharmacopoeia’, hoping that the information contained within “. . . may prove helpful to suffering humanity in regaining and retaining . . . that priceless blessing, good health”. When W. H. Martindale died in 1933 there was no other family member to produce ‘The extra pharmacopoeia’. Concerned, therefore, that this prestigious book might be acquired by a commercial publisher and to protect its own British Pharmaceutical Codex, the Pharmaceutical Society purchased all rights to produce and sell ‘The extra pharmacopoeia’.

Did you know…

Abrus is the first drug monograph listed in the first edition of Martindale, and zotarolimus first appeared in the 35th edition published in 2007

Computerisation and the 21st century

For over a century, ‘Martindale’ in print has been produced by traditional methods, although not quite in the fashion of W. H. Martindale, who pasted foolscap pages endto- end, sometimes resulting in 12 feet of copy being sent for correcting and printing. These manual methods continued to be used until the early 1980s whereby the 28th edition (1982) was the first to be produced electronically by an external company. For the 29th edition (1989), the Martindale database was maintained in-house, thereby giving more control over the data and modernising editorial processes. A computer, the VAX 11/730 system with 470MB of storage, was installed and loaded with content comprising the 28th edition, which was then progressively updated in the course of an edition.

At the end of the revision cycle, computer tapes comprising the 29th edition were sent to an external text processing company to produce suitably coded data for typesetting and for producing online updates. These processes were then brought in-house for the production of the 30th and subsequent editions. The simple but elegant digital solution arrived at has fared extremely well over the decades. It has been adapted, modified, and refined along the way but the basic concept and structure have remained unchanged.

The editorial process to update content is still partly paper-based to this day: amendments and new text are written, checked and edited on computer printouts before being entered back into the database. Rigorous editorial processes are undertaken to ensure the integrity of content updates. however, plans are well under way to move to an entirely paperless editorial system. A digital repository of sources, that enables electronic collection, processing, and storage of data, has been developed, and a web-based editorial interface is under construction.

The information age has reinforced the necessity of a move from traditional print publishing to online delivery. The possibility of developing an online form of ‘Martindale’ was first discussed in 1978 because it was projected that, despite electronic information retrieval still being in its infancy, investing in a new searchable databank service would ensure ‘Martindale’ remained at the forefront of the generation and supply of drug information. Thus, the design and structure for its electronic storage and retrieval were commissioned, and Martindale Online, internationally distributed by commercial vendors, was launched in July 1984. Martindale Online was updated approximately every six months and proved to be a favoured resource. Nowadays, ‘Martindale’ is available electronically on MedicinesComplete (www.medicines complete.com), the searchable online platform of global drug information, hosting renowned resources produced by the Pharmaceutical Press and respected licensing partners. On this platform, ‘Martindale’ is updated quarterly and subscribers have access to content that is not available in the printed editions, including the archive of deleted monographs. Just as William Martindale in 1883 aimed to have the latest and most up-todate information available in ‘The extra pharmacopoeia’, the current online formats of ‘Martindale’ have further realised this.

The most recent development of the digital revolution is the ever accelerating shift from a web-based to a mobile-based method of accessing online information. Furthermore, there is a growing demand and need for continuous updates and flexible content that readily configures into the user’s preferred format. The myriad possibilities that digital content offers are endless and exciting, such as state-of-the-art applications involving interactive data that can be assimilated into the user’s daily workflow and intrinsically embedded into a wider information network. ‘Martindale’ has a long history of adapting to the developing needs of the market and of embracing technological advances. This adaptability will see it retain its position as the leading international reference in drug information well into the next century and beyond.

Conclusion

‘Martindale’ has constantly evolved throughout its long history to meet the changing needs of pharmacists but William Martindale’s original aim — that pharmacists should have access to the most up-to-date pharmaceutical information — has always remained at the heart of the publication. Still of particular pertinence are W. H. Martindale’s last words to his friend, C. E. Sage, just before he died in 1933: “Our work isn’t finished. Carry on. Carry on.” And so we are.

Acknowledgement

Alison Brayfield, lead editor of ‘Martindale: the complete drug reference’ at the Pharmaceutical Press, for her assistance with this article

Exhibition

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society museum has curated an exhibition exploring the 130-year evolution of ‘Martindale: the complete drug reference’. “Martindale: the men and the book — 130 years of pharmaceutical knowledge” is on display at the Royal Pharmaceutical Society Museum, 1 Lambeth High Street, London SE1 7JN until 31 December 2013. Admission is free.