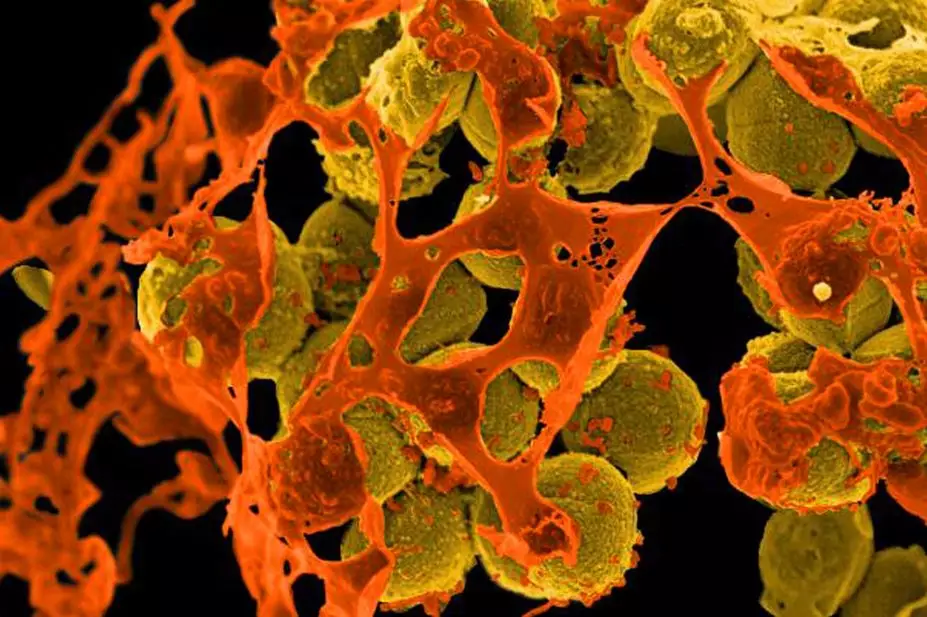

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases / CDC

A new antibiotic that can kill meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) has been discovered in the human nose by researchers at the University of Tübingen in Germany.

The novel molecule lugdunin, which is produced by the bacterial species Staphylococcus lugdunensis, was isolated from samples of human nasal bacteria. In laboratory tests, the researchers discovered it was able to kill a number of harmful bacteria that are resistant to other antibiotics, including vancomycin-resistant enterococci, glycopeptide intermediate-resistant S. aureus and MRSA.

Although usually harmless, S. aureus is present in the nasal passages of 30% of the population. It can become invasive and cause deadly blood infections, especially in people with weakened immune systems. Using antibiotics like mupirocin to remove S. aureus colonies can substantially reduce the chance of infection, but with antibiotic resistance a growing threat to human health, alternative strategies are needed.

To find out how 70% of the population resist colonisation with S. aureus, the research team collected nasal swabs from 187 hospitalised patients. Reporting in Nature

[1]

(online, 27 July 2016), they hoped that analysing human bacteria would lead them to more fruitful discoveries of antibiotics, which are usually isolated from soil bacteria.

Of the nasal swabs collected, the researchers found that 9.1% of those colonised with S lugdunensis had much lower levels of S. aureus. Only 5.9% of these swabs were colonised with S. aureus, compared with 34.7% of the swabs that were not colonised with S. lugdunensis.

This is the first time an antibiotic has been isolated from a human-associated bacteria. Andreas Peschel, from the department of infection biology at the University of Tübingen, says the discovery was “totally unexpected”.

The researchers also found that S. aureus bacteria did not develop resistance to lugdunin, even with exposure already having occurred in people and in repeated exposure in the laboratory. “It seems [lugdunin] can’t develop resistance,” says Bernhard Krismer, a postdoctoral researcher in the department of infection biology at the University of Tübingen.

In mice, lugdunin applied topically was able to either partially or totally eradicate skin infections caused by S. aureus. The team now hopes to partner with a pharmaceutical company to see if the antibiotic can be used to clear S. aureus colonies in people.

The researchers believe that the drug might be able to be taken systemically, because it did not exhibit any signs of toxicity on a sample of human serum. However, lugdunin is not very soluble in water, meaning it might be hard for the body to absorb it. The researchers say the chemical structure might need to be modified to make it suitable for systemic use.

The discovery may also help in the development of new probiotics, suggest the researchers. However, since S. lugdunensis can itself cause opportunistic infections, it is an unsuitable candidate for use as a probiotic. Therefore, the team suggests that the genes from this species could be introduced into a harmless bacterial strain instead.

Colin Garner, chief executive of Antibiotic Research UK, a charity established to tackle the threat of antibiotic resistance, says: “Altering the balance of bacteria in our bodies through the production of natural antibiotics could eventually be exploited to fight off bacterial infections. It is possible that this report will be the first of many demonstrating that bacteria in our bodies can produce novel antibiotics with new chemical structures.”

Garner adds that nose picking and eating snot may not be such a bad habit after all: “Lugdunin and possibly other natural antibiotics might be fighting infections in our bodies all the time.”

- This article was amended on 29 July 2016 to include a comment from Colin Garner.

References

[1] Zipperer A, Konnerth MC, Laux C et al. Human commensals producing a novel antibiotic impair pathogen colonization. Nature 2016. doi: 10.1038/nature18634