Maurizio de Angelis/Science Photo Library

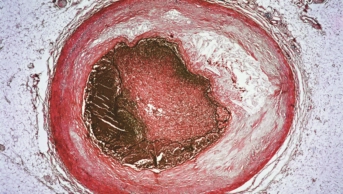

Evolocumab (Repatha; Amgen), a drug that lowers cholesterol by inhibiting the enzyme PCSK9, can significantly reduce the incidence of cardiovascular events when added to statin treatment in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, according to the results of a large multi-national trial.

It had previously been shown that the injectable monoclonal antibody can reduce low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels by around 60% but it was unclear whether this translated to improved cardiovascular outcomes.

“Ostensibly, what this trial has shown is that lowering cholesterol to super low levels, beyond what statins were ever able to do, is safe and lowers the amount of heart attack and stroke,” says Derek Connolly, consultant interventional cardiologist at Birmingham City Hospital, who led the UK arm of the trial.

Conducted between February 2013 and June 2015, the FOURIER trial, funded by Amgen, involved 27,564 high-risk patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease whose LDL-C levels were still at least 70mg/dL (1.8mmol/L) despite optimised statin therapy.

They were randomly assigned to receive evolocumab as a fortnightly (140mg) or monthly (420mg) subcutaneous injection or placebo injection, in addition to their statins.

The average age of patients was 63 years and many were taking secondary preventive drugs, such as antiplatelet drugs, beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors.

To assess the cardiovascular efficacy of evolocumab, the researchers looked at a composite primary endpoint of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, hospitalisation for unstable angina or coronary revascularisation.

After a median follow-up of 2.2 years, the risk of evolocumab-treated patients reaching the primary end point was 15% lower than in patients who received placebo (9.8% versus 11.3%). The risk of the secondary end point, which included just cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction or stroke, was also reduced by 20% (5.9% vs. 7.4%).

Consistent with previous trials, the reduction in LDL-C levels was 59% greater in evolocumab-treated patients than in those who received placebo, dropping from a median of 92mg/dL (2.4mmol/l) at baseline to 30mg/dL (0.78mmol/L) at the end of the study.

Connolly says that the findings are likely to change the way that clinicians view cholesterol levels, allowing them to discard any worries that there might be such thing as having cholesterol that is too low.

“We now know that it’s nothing special about statins, it’s about the LDL-C reduction. We have two other tools we use now [statins and ezetimibe] which we can already use in the war to get cholesterol down. And the big change in mantra is to get the cholesterol as low as we possibly can,” he says.

There was no difference in the cardiovascular or overall mortality rate between evolocumab and the placebo groups in the trial. However, Connolly says that this was expected and is probably because mortality from heart attacks is now relatively low, thanks to advances in treatment, and that people who have already experienced cardiovascular events, as was the case in this trial, are more likely to seek attention at the earliest sign. It could also be because of the relatively short duration of the study.

The research was presented at the American College of Cardiology Annual Scientific Sessions in Washington, DC and was published in the New England Journal of Medicine

[1]

(online, 17 March 2017). Data from the Ebbinghaus safety substudy presented elsewhere at the conference also showed that evolocumab treatment is not associated with worsening cognitive function, which had been suggested could be a consequence of super low LDL-C levels.

FOURIER also showed no difference in adverse events between the evolocumab and placebo groups, with the exception of injection-site reaction (2.1% vs 1.6%).

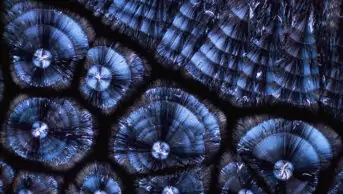

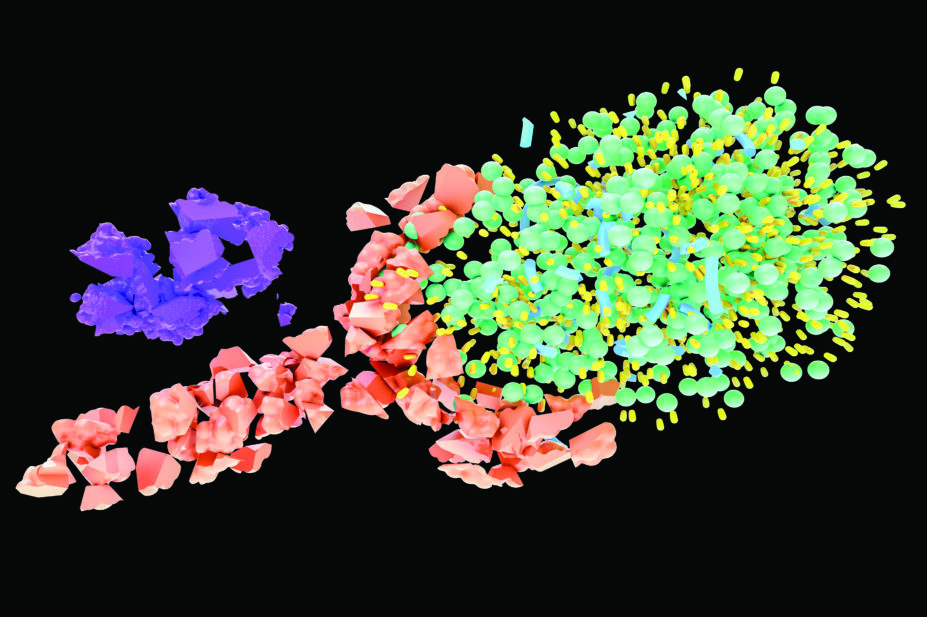

Evolocumab works by targeting PCSK9, an enzyme that breaks down the LDL receptor. Since the LDL receptor is the main mechanism by which cholesterol is cleared from the blood, reducing PCSK9 levels leads to increased LDL receptor levels and decreased LDL-C.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, England’s health technology assessment body, issued a positive opinion on evolocumab in 2016 after reaching a discount agreement with manufacturer Amgen.

The Scottish Medicines Consortium, which advises NHS bodies in Scotland about the status of new medicines, originally rejected the treatment on grounds of insufficient evidence. However, in February 2017, the consortium issued positive guidance for evolocumab after it was resubmitted.

Nilesh Samani, medical director at the charity the British Heart Foundation, said that the results are very important. “If you look at the development of drugs of this type, first of all you understand the mechanism, and then you develop a drug that affects what you think it might affect. But of course, in terms of clinical relevance, you then have to demonstrate that it not only lowers cholesterol but it also lowers the risk of getting cardiovascular events,” he says.

He says that evolocumab is unlikely to be used in patients whose cholesterol levels can be controlled using statins.

“The main benefit, initially for this group of drugs, would be patients who can’t tolerate a statin for some reason — we now have a powerful alternative which we know will drive the cholesterol down and also reduce risk of events — or in people in whom the cholesterol is not in control with the maximum tolerated dose of the statin.”

However, he adds that, as the trial only lasted two years, longer-term studies are needed to assess the long-term safety and to confirm whether evolocumab has any impact on cardiovascular mortality when patients are followed up over a longer time period.

- This story was amended on 30 March 2017. The story originally stated that the Scottish Medicines Consortium rejected evolocumab owing to insufficient evidence. However, the consortium later issued positive guidance for the drug after it was resubmitted.

References

[1] Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC et al. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. NEJM 2017; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1615664