MAG

Seven experts in pain management attended a round-table event on 29 May 2018 to discuss how cÂommunity pharmacy can better support patients to self-manage acute pain with over-the-counter (OTC) treatments. The event, hosted by The Pharmaceutical Journal, was held at the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) headquarters in London.

The expert panel included Emma Davies, pharmacist pain practitioner at Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Board in Wales; Roger Knaggs, associate professor in clinical pharmacy practice and specialist pharmacist in pain management at University of Nottingham; Sunil Kochhar, community pharmacist at Regent Pharmacies in Dartford, Kent; Terry Maguire, pharmacist and honorary senior lecturer at Queen’s University, Belfast; Fin McCaul, managing director and lead pharmacist at Prestwich Pharmacy in Manchester; Andrew Moore, honorary senior research fellow at the Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences at the University of Oxford; and Ash Soni, president of the RPS. They discussed pharmacists’ attitudes towards pain management, the evidence base and how to achieve best practice in pharmacy within the ever-changing landscape of the NHS.

In April 2018, The Pharmaceutical Journal

surveyed members of the RPS to find out how often they spoke to their patients about acute pain, how confident they felt in discussing pain management and what level of training they had completed. More than 1,000 members responded, although not all of these answered every question. The results were presented at the discussion for consideration by the panel.

The respondents consisted mainly of community pharmacists (58%), with some students (15%) and hospital pharmacists (10%), and a small number of preregistration trainees, pharmacy technicians, counter assistants and pharmaceutical scientists. Around a third of the respondents said they worked for a large pharmacy multiple.

Around 35% of respondents stated that, on average, they spoke to adult patients about acute pain around two to five times per day. Just over 8% said that they spoke about pain more than ten times per day, while 6% admitted that they never spoke to adult patients about acute pain.

Knaggs said there was a “very large role” for pharmacists in dealing with pain. “Pharmacists could be doing a lot more to help patients with OTC analgesics,” he added.

Training and confidence

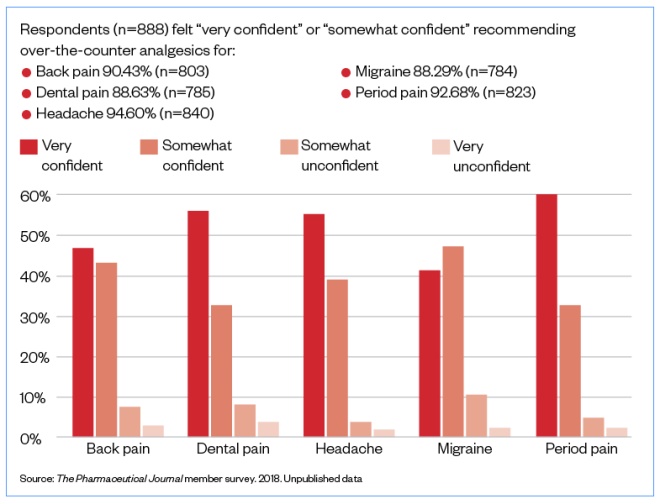

Confidence in recommending OTC analgesics for pain relief in adults appeared to be high among respondents (see Figure). However, when questioned on when they had last completed training on pain management, answers varied.

Less than a quarter of respondents said they had completed training in the past year; 17% stated they had received training three or more years ago; 33% claimed that they did not remember when they last received training; and 8% admitted they had never completed any training on pain management.

Davies said these results were reflected in a study on pharmacists and pharmacy technicians, conducted on behalf of the chief pharmaceutical officer in Wales.

How confident are you in recommending over-the-counter analgesics for pain relief in adults?

Source: The Pharmaceutical Journal member survey. 2018. Unpublished data

“Pharmacists, in particular, were very confident around questions on doses, but when you asked about training since qualification, very few had had formal educational training on pain,” she said.

“If people said they haven’t had training, their knowledge of analgesics will have come from undergraduate training — which could have been 20 years ago.”

Kochhar highlighted the variety of training available but noted that there needs to be more of an opportunity for pharmacy teams to develop further. Maguire added that because community pharmacists have “exceptional confidence” in this area, it is difficult to point out that their knowledge may be outdated and no longer considered best practice. “The challenge, first of all, is to try and address that straight on,” he said.

Moore agreed, saying it was easy for people to carry on with what they think they know instead of “going out and finding what the truth is”.

Soni noted that practice differed between different generations of pharmacist: “Older pharmacists are the most difficult to get to change their behaviours and habits — how do we behaviourally get them to recognise that their knowledge is inaccurate? Complacency is out there.”

McCaul said: “We need a shock to change ways of working — pharmacists don’t know as much [about pain] as they need to.”

Pharmacists’ perspective on pain

At the round-table event, McCaul presented the unpublished results of a survey involving 305 pharmacists, conducted by IMS Health on behalf of RB, which aimed to find out more about their attitudes towards different OTC analgesics, the barriers to recommendation and their perceptions of ibuprofen versus paracetamol.

According to the IMS Health survey, McCaul said “the vast majority” of pharmacists believed that paracetamol was safer than OTC ibuprofen, but almost half were neutral about its efficacy compared with OTC ibuprofen. However, many respondents described paracetamol as “good enough”, probably owing to their perceptions of safety, he explained.

When asked about adverse events associated with OTC ibuprofen, it appeared that general levels of knowledge were low, as 30% of respondents answered “don’t know” to questions on this topic.

Respondents also said they would avoid recommending OTC ibuprofen to people with sensitive stomachs and minor gastrointestinal problems, and more than 75% of respondents said they believed that OTC ibuprofen should be taken with or after food. Paracetamol was perceived as gentler on the stomach and better tolerated.

McCaul highlighted that there was no evidence that food offers gastroprotective effects when taking OTC ibuprofen: instead, eating food can delay drug absorption and impair the time to optimum efficacy. The recommendation is to take OTC ibuprofen with water, he said.

When exposed to the current evidence around efficacy and safety, all participants surveyed admitted that at least some of the information was new to them. Some added that the evidence presented in the IMS Health survey contradicted personal experience — one respondent said that although the evidence sounded believable, it went “against everything I have been taught in my pharmacy career”.

The respondents to The Pharmaceutical Journal’s survey were asked to rank the OTC analgesics they sold in their pharmacy in order of those they would recommend most commonly for acute pain: 70% of respondents put paracetamol as the first choice, and 57% said ibuprofen would be their second choice.

This survey also used a case study to understand practice-based decisions: “A 30-year-old woman comes into the pharmacy complaining of acute pain. Assuming you know her history and there are no medications she cannot take, what are your first-line and second-line recommendations for each of the following types of pain?” The range of treatments suggested by the respondents are summarised in the Table. When asked for the rationale behind these choices, most respondents said it was because of the active ingredient in the drug and/or its efficacy. However, it should be noted that the

British Association for the Study of

Headache guidelines for treatment of migraines

state that the first step of the ‘treatment ladder’ should be OTC analgesics and anti-emetics, and that these should be used without codeine.

The Pharmaceutical Journal’s survey also aked whether respondents believed that paracetamol was better than ibuprofen for pain relief. The majority of respondents (87%) said it depended on the type of pain, as paracetamol and ibuprofen have different mechanisms of action.

Although 32% of respondents claimed there was some benefit of analgesics with added caffeine for headache, it was noted that around a third of respodents for each type of pain felt that more data were needed to confirm the benefits of those with added caffeine.

| Pain type | First-line treatment | Second-line treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analgesic | Number of respondents | Analgesic | Number of respondents | |

| Source: The Pharmaceutical Journal member survey. 2018. Unpublished data | ||||

| Back pain | Ibuprofen | 32.21% (n=229) | Co-codamol | 22.11% (n=134) |

| Dental pain | Ibuprofen | 24.47% (n=174) | Co-codamol | 18.81% (n=114) |

| Headache | Paracetamol | 72.96% (n=518) | Ibuprofen | 24.09% (n=146) |

| Migraine | Co-codamol | 22.43% (n=159) | Co-codamol | 17.00% (n=103) |

| Period pain | Naproxen | 32.44% (n=230) | Naproxen | 22.44% (n=136) |

Moore, who presented

Cochrane efficacy data on OTC oral pain relief

to the panel, highlighted that ibuprofen and caffeine had been proven to be a very good mix, and that caffeine can add a lot to pain relief.

“The best analgesic is 200mg fast-acting ibuprofen, 500mg paracetamol and a cup of coffee — many come back and say ‘it’s really good’ — when the evidence is solid, it works,” he said.

The round-table panel concurred that practice and training need to reflect the most up-to-date evidence. “There’s so much good evidence out there, and [pharmacists] are not taking it on board,” said McCaul.

Potential barriers

The respondents said that very few barriers existed to prevent them from recommending OTC analgesics to adults for acute pain, with more than 50% saying there were no barriers at all. However, just under 14% said they would only recommend OTC analgesics if their patient asked about them; around 12% said they felt they did not know enough about the contraindications for OTC analgesics; and more than 10% felt that they did not know enough about the different mechanisms of action for OTC analgesics.

Some respondents commented that a barrier might occur if they felt the analgesics were being purchased too often or if they thought the patient might be addicted. Others stated that their biggest concern when selling acute medicines was overuse, including requests for codeine-containing products for more than three days of use.

It was noted by one respondent that many patients have already decided which pain medicine they want before coming to the pharmacy. “Talking to them to find out if their chosen drug is appropriate just tends to annoy them,” they wrote.

Soni concurred and said that sometimes patients come with set expectations when it comes to OTC analgesia, as is often the case when patients are seeking antibiotics. “There is evidence of patients wanting a pill and if you recommend something else they won’t want to accept that,” he said.

“It’s not just about the analgesic, but about all the other parts of it, including exercise — if that becomes part of the wrap-around package, we head towards holistic care.”

Patient-centred care

Maguire said pharmacists must take a step back and approach pain management from a self-care perspective, enabling patients to make decisions about their own health. However, he acknowledged that a self-care framework for pharmacists had not been properly articulated and pharmacists should be looking at pain management in a more holistic sense — for example, by using the ASMETHOD (age and appearance, self or someone else, medication, extra medicines, time persisting, history, other symptoms, danger symptoms) framework — in order to view the patient as an individual and to enable the identification of red flags.

“We need to combine public health messages with acute management — pharmacists are not there to diagnose, but to differentiate between self-limiting, acute conditions and something that’s potentially more sinister and needs referral,” he suggested.

Davies pointed out that the British Pain Society recommends healthcare professionals ask two questions about pain: “What is it stopping you from doing?” and “How is it making you feel?”

Kochhar added that there needs to be an empathetic conversation with patients; rather that simply “regurgitating information”, pharmacists should ask whether the analgesics are helping. “It’s about engagement with patients”, he explained. Kochhar also highlighted the importance of

motivational

interviewing

and encouraging patients to come back and tell their pharmacist how they are progressing with their treatment.

“Clinical pharmacists must not underestimate the ignorance among patients,” said Moore, adding that 5% of patients said they thought the maximum for paracetamol was 10,000mg per day.

“This opens up [the opportunity] for another conversation — pharmacists are ideally placed to get patients to think about that,” he noted.

Involving the whole pharmacy team

Respondents to The Pharmaceutical Journal’s survey were asked who in their pharmacy talks to patients about pain: more than 75% of respondents said the medicines counter assistants, almost 63% said the dispensing assistants, and over 55% said the pharmacy technicians.

The panel agreed that achieving best practice in this area requires the entire pharmacy team to be empowered to work to the top of its licence.

“What about pharmacy staff — do they have the confidence?” asked Soni. “Does their knowledge come from the pharmacist? Counter assistant training and staff development has not evolved much either.

“It requires judgement to decide how roles are allocated in the pharmacy team; it can’t just be a blanket ‘everyone could do this’ because skills vary,” added Soni, arguing that pharmacies have champions for issues such as smoking, so why not have the same for pain management.

One respondent said that it would be good to have a “more standard approach” to OTC treatment of both acute and chronic pain, as many patients report that their pain is acute when it is actually a flare-up of a chronic condition. They added that they felt co-codamol is used far too often and many pharmacies do not ask ‘WWHAM’ questions — who is the medicine for, what are the symptoms, how long have the symptoms lasted, what action has been taken already, and are they taking any other medication? Instead, the respondents claimed, pharmacists sell co-codamol for various ailments, even when they report that the patient buys it frequently.

However, Maguire suggested that the WWHAM method may no longer be sufficient — while it was introduced as a means of getting the necessary information from the patient quickly and efficiently, it has now turned into a tick-box exercise rather than a means to take action.

“My view is that pharmacists must now intervene, as only they have the knowledge to decide if the medicines are important in the context of the symptoms and the medicine that might be supplied,” he told The Pharmaceutical Journal

. “But this does not happen — too often the priority is to ensure the question is asked then the medicine is supplied.”

He added that WWHAM is also limited because it does not consider wider issues, such as ageing, and behaviours that impact on the system, including smoking.

Moving forward

The Pharmaceutical Journal will use insights taken from the survey and the meeting to commission learning and CPD content that aims to help pharmacy teams better support patients with short-term use of OTC analgesics.

McCaul said he felt there were two things that needed to change to improve pain management in pharmacy. The first was for guidance from the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency and for summaries of product characteristics to be aligned — something, he suggested, that the RPS could help put in motion. Secondly he said that other organisations must be involved, such as the Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education, to strengthen the message of promoting the role of pharmacists in this area and be “a driver to change”.

“Pharmacists could potentially treat patients better than GPs can — and they’re more accessible and have more tools in their armoury,” he said, adding that there were “a whole host of messages to get pharmacists to do something different”. The biggest problem was changing habits.

Soni agreed that it was “essential” for the RPS to provide standards and support to professionals, backed up by the best evidence, in order to increase confidence and maintain credibility.

“Pharmacists are being seen in a more critical role — people come in to seek advice quickly,” he said. “Having access to the right information gives confidence to pharmacists and their teams, and to the public.”

He suggested that pharmacists should be asked specific questions to get them to realise the limits of their knowledge in the area of pain, and consequently their ongoing need for training. “Five questions you know they’re going to get wrong, [but] their assumption is that they’ll get them all right. That’s what triggers the change,” he said.