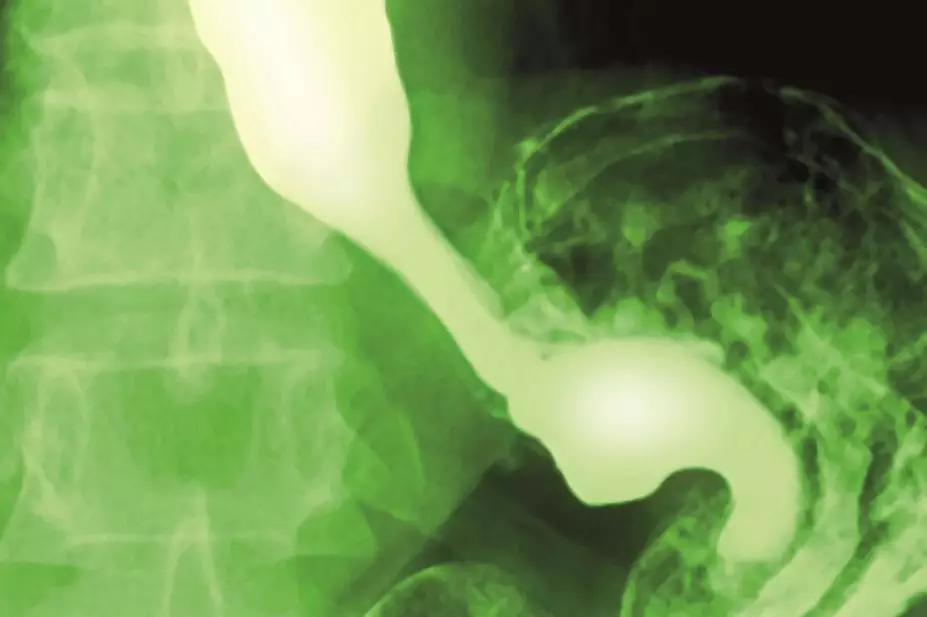

Miriam Maslo / Science Photo Library

People who take proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), commonly used drugs for heartburn, have a greater risk of suffering a heart attack whether or not they have any history of cardiovascular disease, suggests a data-mining study.

Researchers assessed data involving 16 million clinical documents on 2.9 million individuals for pharmacovigilance information.

Patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease who took PPIs, whose main action is to reduce the production of gastric acid, were more likely than the general population to suffer a heart attack (adjusted odds ratio 1.16; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.09–1.24), while alternative heartburn therapies, H2 blockers, were not associated with an increased risk.

Survival analysis in a prospective cohort found a two-fold (hazard ratio 2.00; 95% CI 1.07–3.78; P = 0.031) increase in association with cardiovascular death.

Had the data-mining approach used in this study been available earlier, a correlation between heart attack risk and two PPIs in particular, lansoprazole and omeprazole, would have been spotted as early as 2000, wrote the study’s lead researcher Nicholas Leeper, assistant professor of surgery and medicine at the Stanford University Medical Center, and colleagues, in the journal PLOS ONE

[1]

on 10 June 2015.

Previous studies have shown a link between PPIs and the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients who take the antiplatelet drug clopidogrel, which is used to treat blood clots in patients with cardiovascular disease. In this latest study, the increased risk of heart attack was not affected by clopidogrel use.

Some 113 million PPI prescriptions are dispensed globally each year. About 21 million people in the United States used one or more prescription PPIs in 2009, making it the third highest seller in the country. This is the first time that an increased risk of heart attack has been found in patients who take PPIs but have no prior history of cardiovascular disease.

“Although other research has not shown such an association, the study throws up some interesting findings and certainly merits further investigation,” said Anton Emmanuel, consultant gastroenterologist at University College London Hospitals (UCLH), a spokesperson for the British Society of Gastroenterology. “There is certainly correlation; however this does not necessarily imply a causal link and therefore we must be careful about jumping to conclusions too quickly.”

“Our observation that PPI usage is associated with harm in the general population — including the young and those taking no antiplatelet agent — suggests that PPIs may promote risk via an unknown mechanism that does not directly involve platelet aggregation,” Leeper and his team write, and suggest that the mechanism may involve dysregulation of vascular nitric oxide synthase.

The study was based on patient data from two sources: Stanford’s hospital system (Stanford Translational Research Integrated Database Environment or STRIDE); and a company called Practice Fusion, which provides a free, web-based electronic health record (EHR) system for clinicians.

“Most long-term side effects aren’t caught during clinical trials, but we can now run virtual post-market clinical trials simply by analyzing a ton of real-world data (ie, millions of de-identified patient records) that physicians are collecting and entering about their patients in the secure Practice Fusion cloud,” said Justin Jones at Practice Fusion, the company that provided data on 1.1 million anonymous outpatients in the study.

There is now an enormous amount of data that could help determine if one medication is more efficacious than another. Or, as in this case, unexpectedly deleterious.

“The long-term power and value of electronic health records is largely in the massive de-identified clinical datasets like we have built and are growing rapidly,” said Jones.

| Table: Proton pump inhibitor use is associated with an increased risk for heart attack | |

|---|---|

| Proton pump inhibitor | Odds ratio (95% CI) (derived from STRIDE data) |

| Source: PLoS ONE | |

Pantoprazole | 1.34 (1.16-1.55) |

Omeprazole | 1.26 (1.12-1.42) |

Lansoprazole | 1.24 (1.06-1.45) |

Rabeprazole | 1.12 (0.88-1.41) |

Esomeprazole | 1.08 (0.88-1.31) |

References

[1] Shah NH, LePendu P, Bauer-Mehren A et al. Proton pump inhibitor usage and the risk of myocardial infarction in the general population. PLoS ONE 2015;10(6): e0124653. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0124653.