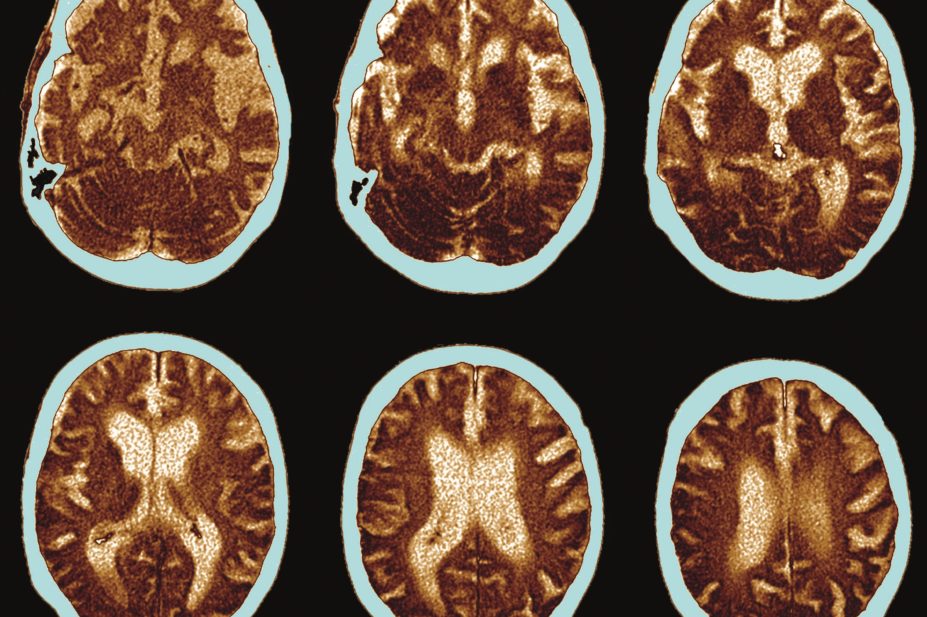

Science Photo Library / Alamy Stock Photo

An enzyme closely linked to brain changes in Alzheimer’s disease also seems to have a role in glucose control, according to a study published in the July 2016 edition of Diabetologia

[1]

.

The study shows for first time that dementia-related complications within the brain can also lead to changes in glucose handling and ultimately diabetes, the researchers say. Diabetes is otherwise thought to begin with a malfunction in the pancreas or a high fat, high sugar diet.

Previous research has linked diabetes with a risk of getting Alzheimer’s disease. Lead researcher Bettina Platt, based at the College of Life Sciences and Medicine at the University of Aberdeen, Scotland, says: “Many people are unaware of the relationship between diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease, but the fact is that around 80% of people with Alzheimer’s disease also have some form of diabetes or disturbed glucose metabolism. This is hugely relevant as Alzheimer’s is in the vast majority of cases not inherited, and lifestyle factors and comorbidities must therefore be to blame.”

Source: University of Aberdeen

Lead author Bettina Platt says the study has showed that dysregulation in the brain can equally lead to the development of very severe diabetes

Platt adds that her research teams are “particularly interested in the impact of lifestyle related factors in dementia and by collaborating with experts in diabetes and metabolism, we have been able to investigate the nature of the link in great detail”.

“Until now, we always assumed that obese people get type 2 diabetes and then are more likely to get dementia – we now show that actually it also works the other way around,” she says.

The research involved mice, genetically engineered to produce β-Secretase1 (BACE1), an enzyme involved in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. The enzyme catalyses the amyloidogenic cleavage of amyloid precursor protein (APP) and it may have a role in glucose homeostasis because its absence has been shown to protect against diet-induced obesity and diabetes. The researchers found that the mice bred to produce BACE1 showed signs of poor glucose control when compared with “normal” mice.

Physiological and molecular analyses showed that the mice engineered to produce BACE1 demonstrated diabetic signs, notably systemic glucose intolerance from the age of four months onward, alongside a fatty liver phenotype and impaired hepatic glycogen storage.

Platt says it had been believed that diabetes starts in the pancreas and liver, often caused by an unhealthy diet, but this study has showed that “dysregulation in the brain” can equally lead to the development of very severe diabetes.

She says the study provides a new therapeutic angle into Alzheimer’s disease and believes that some of the compounds used for obesity and diabetic deregulation could potentially be beneficial for Alzheimer’s patients as well.

“The good news is that there are a number of new drugs available right now that we are testing to see if they would reverse both Alzheimer’s and diabetes symptoms,” says Platt.

James Pickett, head of research at the Alzheimer’s Society, says there is already evidence of an association between type 2 diabetes and the risk of Alzheimer’s, but the underlying mechanisms that could link the two are so far unclear.

“The gene studied here, called BACE1, has long been known to contribute towards Alzheimer’s disease,” he says. “In this research, mice were used to identify what role this gene could play in the development of both Alzheimer’s and diabetes. However, more research is needed to understand whether this relationship is also true in people.”

Pickett points out that this research does not mean people with diabetes should be unduly worried about their risk of getting dementia.

Emily Burns, research communications manager at Diabetes UK, says it is known that having type 2 diabetes can increase a person’s risk of developing dementia. “But as it stands, we don’t know why that link exists, or which condition might come first,” she says. “This study is helping to unravel that complex question, suggesting that having Alzheimer’s disease may in fact increase a person’s risk of developing type 2 diabetes.”

But she adds: “While this area of research could potentially help to combat the progression of both conditions in the future, we are currently at a very early stage and need to see if the results apply in a human setting.”

References

[1] PluciÅ„ska K, Dekeryte R, Koss D et al. Neuronal human BACE1 knockin induces systemic diabetes in mice. Diabetologia July 2016; 59:1513–1523. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-3960-1