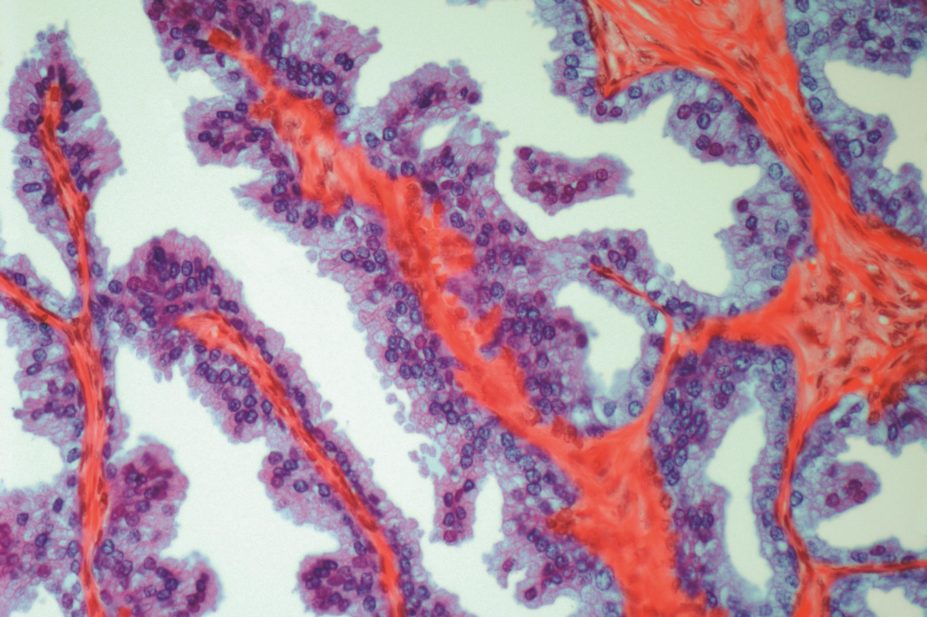

Steve Gschmeissner / Science Photo Library

A third of men with advanced prostate cancer could benefit from a drug currently licensed for women with ovarian cancer, according to the “remarkable” results of a study.

Men with mutations in DNA repair genes were found to have a high response rate to olaparib — marking a step towards tailoring prostate cancer treatment to individuals. This biomarker-positive group also had drastic improvements in survival compared with the biomarker-negative men who were also given the drug.

“These findings are truly remarkable given the extensive amount of therapy that these patients have already received,” says Ganesh Raj, associate professor of urology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, who was not involved in the research.

The phase II study, published in The

New England Journal of Medicine

[1]

on 28 October 2015, was carried out at the Royal Marsden Hospital and Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) in London. It involved 50 men with treatment-resistant metastatic prostate cancer who were given olaparib at a dose of 400mg twice a day. DNA samples from tumour cells and from healthy tissues were taken. Analysis of these samples using next generation sequencing revealed that 16 of the 49 men had mutations in DNA repair genes either in the germline DNA sequence or in tumour DNA.

Out of 49 men who completed the study, 16 responded to treatment with olaparib (33%). Of these, 14 were part of the group identified as having mutations in their DNA repair genes, a response rate of 88%. In comparison, only two men who were biomarker-negative responded to treatment (6%). Average survival was 13.8 months in the biomarker-positive group compared with 7.5 months in the biomarker-negative group (P=0.05).

Chief investigator Johann de Bono, head of drug development at the ICR and Royal Marsden, says the results show that olaparib is highly effective at treating men with DNA repair defects in their tumours. “I hope it won’t be long before we are using olaparib in the clinic to treat prostate cancer, or before genomic stratification of cancers becomes a standard in this and other cancers,” he adds.

Raj says that using biomarkers to plan treatment would be a “game changer”. The vast majority of prostate cancers have actionable mutations so the findings of the current study “offer new hope to patients with advanced prostate cancer”, says Raj.

Olaparib was recommended for approved by the European Medicines Agency in October 2014 and was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in December 2014 for the treatment of women with ovarian cancer and mutations in the BRCA2 DNA repair gene, which also increases the risk of breast cancer. When DNA repair genes like BRCA2 are faulty, cancer cells become reliant on the action of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) protein, which also repairs DNA. Olaparib blocks the action of PARP. By blocking the protein, the cancer loses the ability to repair DNA and so the cell dies.

Seven men in the Royal Marsden/ICR study were found to have mutations in BRCA2 and all of these men responded to treatment, with at least a 50% drop in the level of prostate specific antigen (PSA) in the blood. The other men had mutations in other genes also involved in DNA repair.

The researchers are now performing a second study with olaparib consisting solely of men who have tested positive for DNA repair mutations.

Prostate cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in men in the UK.

In August 2015, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence issued preliminary guidance rejecting olaparib for use in the NHS for adults with relapsed, platinum-sensitive ovarian, fallopian tube or peritoneal cancer who have BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. A final decision is expected in January 2016.

References

[1] Mateo J, Carreira S, Sandhu S et al. DNA-repair defects and olaparib in metastatic prostate cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2015. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1506859