The slowing in the rate of increase of life expectancy in the UK is “as urgent as our winter bed crisis and should be taken as seriously,” according to Michael Marmot, professor of epidemiology and director of the Institute for Health Equity at University College London (UCL)

Between 2011–2015, the average increase in UK life expectancy slowed dramatically to half of the rate seen in the 100 years prior. Europe-wide data from that five-year period put the UK at the bottom of the list for increase in female life expectancy, and second from bottom for male life expectancy.

This stark analysis was the opener for Marmot’s 2018 UCL School of Pharmacy/Royal Pharmaceutical Society New Year Lecture, ‘Reducing Health Inequalities’.

Delivering his lecture on 16 January 2017, Marmot said that while increases in life expectancy across Europe generally slowed over that same period, the situation in the UK was more marked than anywhere else.

In the 100 years leading up to 2010, life expectancy for women had increased, on average, by 1 year every 5 years. For men, the rate of increase had generally been 1 year every 3.5 years. But between 2011–2015 a “dramatic” flattening of that ‘slope’ took pace in the UK, to a rate of 1 year every 10 years for women, and 1 year every 6 years for men.

So, what has gone wrong, Marmot asked, and what can we do about it?

Marmot, who described himself as having a “social determinist” approach to public health, used his lecture to share six areas of where he could make recommendations, including creation of fair employment, sustainable communities and addressing child poverty. These recommendations were taken from The Marmot review, an independent review commissioned by the then Secretary of State for Health that aimed to propose the most effective evidence-based strategies for reducing health inequalities in England from 2010.

The recommendations make, as a starting point, a link between health inequalities and social inequalities. Action to reduce health inequalities must, Marmot said, focus on all the “social determinants of health”.

Currently, he said, our health is not improving as it should be. He hesitated to put the blame entirely on austerity measures, but he argues that it is a matter of urgency to investigate the relationship between the two. The average rise in health care expenditure from 2010 onwards has shown a “marked slowing”, sitting at around 1.1% per year “when historically it was more like 3.7%.”

He added that spending on the adult component of social care between 2009–2010, and the 5 years after, was reduced by more than 6%, even though our population continued to age. “That will impact on older people, and we must investigate whether it’s affecting length of life of older people,” he said.

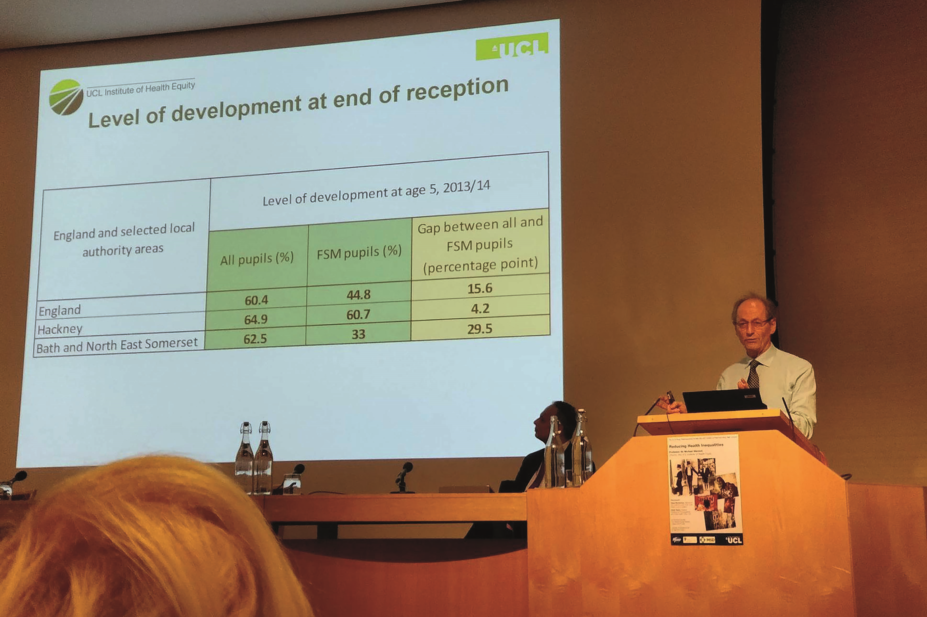

Marmot also stressed the importance, when analysing the health of a nation, of considering the gaps between a nation’s social groups rather than simply considering overall averages. After the Grenfell Tower fire, Marmot looked at life expectancy across the borough of Kensington and Chelsea and found a gap of 14 years between residents who lived in the area around Grenfell Tower, and residents of the nearby ambassadorial street. “We can’t possibly say ‘we’re just interested’ in the average [figures]”, he said. “That would be missing the major public health problem that’s staring us in the face.”

Expanding on this point, he referenced research from the University of Liverpool, published in 2017, which analysed whether New Labour’s 1997–2010 strategy to reduce health inequalities had been effective. The researchers looked at life expectancy around this period in the fifth most deprived local authority areas in England, and compared the figures to the rest of the country. The researchers reported that between 2002 –2011 the gap had narrowed, but since 2013 it gap began to widen once again. “Policies can make a difference”, Marmot said. “We can have narrower health inequalities, if we choose to have them.”

In the press conference prior to the lecture, Marmot discussed the potential impacts of Brexit. He referenced a Joseph Rowntree Foundation report that observed a link between the vote and measures of economic distress. “Most people with a university education voted to remain, as did leaders of the medical and legal profession, most scientists, most economists, even most MPs,” he said. “People with an education, by and large, voted to remain. There are one or two prominent figures who deny the benefits of their education and voted some other way.

“We see this link between social disadvantage, ill health and voting that affects the whole of society. I want to talk about what we can do to make a difference.”

Expanding on this point, Marmot pointed out that 92% of economists voted to remain. “They hold a strong view that we would be damaged economically. We will have less resources to spend,” he said. But he emphasised that while much time is spent discussing the disadvantages of leaving, he would like to focus on the positives of remaining. “Sharing is a good thing. The problems we face go beyond any one country. Do we deal with tax avoidance, safety in medicines, co-operation on Euratom as a one-country solution?

“We should see Europe as a positive thing. Brexit diminishes all of us — we lose these positives.”

Researchers have a vested interested, he added, saying that there was “no way in the world” that the European research budget was going to be made up domestically after Brexit. “Britain benefits enormously from the EU research budget, and from co-operation with EU partners, because we’re so good at this stuff.”