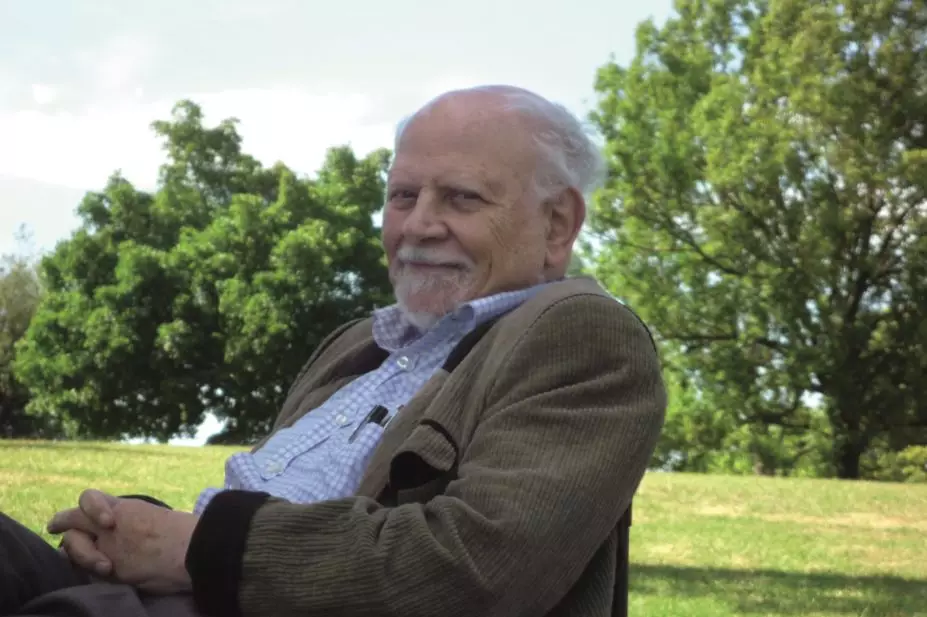

Christine Herxheimer

Andrew Herxheimer, the clinical pharmacologist who died following a stroke aged 90, was founder, in 1962, of the Drugs and Therapeutics Bulletin (DTB), which he edited for 30 years.

By the time he left in 1992, the DTB, published by the Consumers’ Association, had a circulation of 90,000 and was sent to all NHS doctors and pharmaceutical advisers in England, thanks to a bulk subscription funded by the Department of Health. When this arrangement ended in 2006, the DTB was bought by the BMJ Group.

“Years before evidence-based medicine really took off, Andrew saw the need for independent advice on drugs and treatments in the interests of patients,” says Joe Collier, brother of Herxheimer’s first wife Susan Collier and emeritus professor of medicines policy at St George’s, University of London, who worked on DTB in the early days and then went on to edit it from 1992 to 2004.

“He was an intellectual, obsessional visionary, and a very good writer. DTB was a think tank for medicines policy.”

Each article was commented on by 20 to 30 consultants, plus the manufacturers concerned. “The aim was an accurate, impartial and clearly expressed consensus view that prescribers could use,” says Collier, brother of Herxheimer’s first wife. “Andrew was resolute. Articles had to reflect the best knowledge available and if this ruffled feathers so be it.”

Patrick Vallance, president of pharmaceuticals research and development at GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), previously professor of clinical pharmacology at University College London, says: “DTB was way ahead of its time and had enormous impact on doctors’ way of thinking. It was extremely well written and provided succinct advice on what to prescribe.”

Vallance, a former member of the DTB advisory board, adds: “It set a path that led to other developments. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) came from what the DTB was trying to do.”

Sir Michael Rawlins, chair of the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency and former chair of NICE, knew Herxheimer well. “He had a major impact on clinical pharmacology quite apart from the DTB,” he says. “He was delightfully argumentative and always stirring things up in a positive sense. And in later years he had a major impact on the Cochrane Collaboration.”

Born into a Jewish family in Berlin in 1925, Herxheimer came to London in 1938, escaping Nazi Germany aged 12 with his mother Ilse (née Konig) and sister Eva.

They joined his father, Herbert Herxheimer, a physician specialising in sports physiology, who had been invited to England by the nobel prize winner Archibald Hill after they met at the 1936 Berlin Olympics. Hill was active in helping academic refugees through the Society for the Protection of Science and Learning, and found Herbert Herxheimer a job as a doctor to Highgate School in London.

Andrew, great nephew of the dermatologist Karl Herxheimer, who is credited with identifying an inflammatory reaction to antibiotics, was given a bursary and attended the school, where he was secretary of the chess club and member of the science society from January 1939 to July 1944.

He won a scholarship to St Thomas’ Hospital medical school, qualifying in 1949 and was lecturer and senior lecturer in pharmacology at London Hospital Medical College between 1959 and 1976, before spending 15 years as senior lecturer and consultant at Charing Cross Hospital and Westminster Medical School. He served on the British National Formulary Committee from 1966 to 1973 and was extraordinary professor of clinical pharmacology in Groningen, Holland, from 1968 to 1977.

After leaving the DTB in 1992, he became a founding member of the Cochrane Collaboration and remained involved with the organisation for the rest of his life. In December 2015 he was made a fellow of the British Pharmacological Society.

Herxheimer founded the Database of Individual Patients’ Experience of Illness (DIPEx) and healthtalk, which now covers 90 conditions.

Angela Coulter, senior research scientist at Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, says: “Andrew’s contribution to ensuring patients are fully informed about their medical care — benefits, harms and uncertainties — was second to none. We should all be grateful for this outstanding legacy.”

He remained a fierce advocate of medical decisions being evidence based and transparent all his life. In January 2014, when the chief medical officer Dame Sally Davies wrote an alert and letter endorsing the use of the antiviral drugs oseltamivir and zanamivir for patients with influenza symptoms, Herxheimer was one of three signatories to a response in The BMJ. “Withdraw the alert and letter; insist the pharmaceutical industry puts all the evidence in the public domain; review the evidence and publish it correctly to inform prescribers, pharmacists and the public about these drugs” (

The BMJ 2014;348:g13).

Herxheimer, who spoke English, French, German and Dutch, was an adviser to the World Health Organization on pharmaceuticals and drug dependence, and was active in many international networks until the time of his death.

He is survived by two daughters, Charlotte and Sophie, from his first marriage to the late Susan Collier, a textile designer, which ended in divorce, and by his second wife, Christine, a psychiatrist whom he married in 1983.

Christine Herxheimer says: “Andrew was so determined to lead a useful life that even when he was in the Royal Free hospital in February with a mild heart attack he was handing out leaflets on healthtalk. And he was editing up until the day before he died.”

You may also be interested in

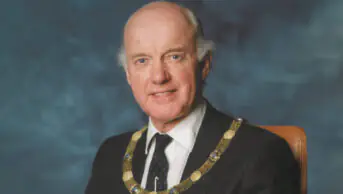

Philip Leon Marshall Davies (1938–2026)

Bill Scott OBE (1949–2025)