Peter Stone / Alamy Stock Photo

On 8 October 2015, British artist Damien Hirst’s Newport Street Gallery in south London opened its door to the public with an exhibition of John Hoyland’s Power Station paintings. Hirst is perhaps better known for his controversial artworks such as his diamond encrusted platinum skull, For the Love of God (2007), and Mother and Child (Divided) (1993) — a bisected cow and calf preserved in formaldehyde, which was the focal piece for the his winning 1995 Turner Prize competition entry.

But, to the pharmacy community, Damien Hirst is known for his unusual preoccupation with the profession. The artist has explored pharmacy through various types of artworks such as his spot and remedy paintings, the 13 print series ‘The Last Supper’ and the medicine cabinets.

Hirst’s first medicine cabinet artwork Sinner (1988) is an unusual and touching portrait of his grandmother who suffered from lung cancer, using the medicines that she left for the artist upon her death as a medium. A second cabinet quickly followed — Enemy (1988-89) was regularly updated with new medicine packaging to ensure it always looked contemporary. Hirst’s idea of using medicines packaging as a medium was eventually applied to a room-sized installation entitled Pharmacy (1992), which was first shown in the Cohen Gallery in New York. It was the first artwork that greeted visitors upon exiting the lift and Hirst recalls that visitors often mistook the installation for a real pharmacy and asked “Where is the Damien Hirst exhibition?” Hirst defined the confusion as art and enjoyed the illusion the artwork created.

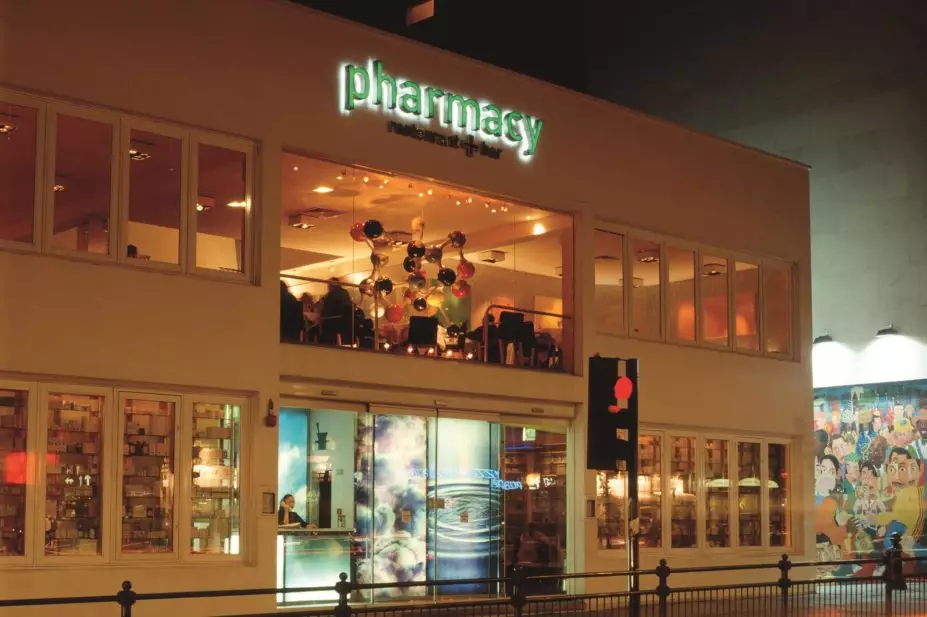

While the installation was on display at the Tate Modern in 1998, Hirst launched his collaborative restaurant venture in Notting Hill called Pharmacy. The artist designed the interior of the restaurant, which had aspirin tablet-styled bar stools, medicine cabinets and distinctive pharmacy-themed wallpaper. Its staff wore surgical gowns and the bar served cocktails with names such as Voltarol Retarding Agent.

The restaurant won the prize for best-designed restaurant from the Carlton London Restaurant Award. It did, however, court controversy with the then Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (RPSGB). The RPSGB took legal action because the naming of the restaurant went against section 78 of the Medicines Act 1968. Section 78 imposes restrictions on the use of titles, descriptions and emblems and it states “No person shall, in connection with a business carried on by him which consists of or includes the retail sale of any goods, or the supply of any goods in circumstances corresponding to retail sale, use the description “pharmacy” except in respect of a registered pharmacy or in respect of the pharmaceutical department of a hospital or a health centre.”

It also states that “For the purposes of the last preceding subsection the use of the description “pharmacy”, in connection with a business carried on at any premises, shall be taken to be likely to suggest that the person carrying on the business (where that person is not a body corporate) is a pharmacist”. The restaurant was clearly not a registered pharmacy and Hirst is not a pharmacist.

The Society also took legal action because the restaurant misled the public. Hirst even recalls a customer asking for aspirin to which he replied “I’m sorry, but we have a strictly no drugs policy here!” Hirst was amused and indulged in the confusion. Following these legal threats, the restaurant was then transiently named Army Chap (an anagram for Pharmacy) before settling on Pharmacy Restaurant and Bar. This was still an unsatisfactory change, but the Society was advised that it satisfied the law and the case was, therefore, subsequently dropped. The restaurant closed in 2003 due to financial and management issues.

It is, however, apparent that Hirst intends to revisit this controversy with the naming of the restaurant attached to his new gallery, “pharmacy2 ”, which is due to open next year. It has, according to Oliver Wainwright (The Guardian’s architecture and design critic), walls lined with pills and surgical tools and terrazzo floor inlaid with water-jet cut marble tablets. At first glance, pharmacy2 will once again breach the 1968 Medicine Act because ‘pharmacy’ remains a restricted title. The use of the superscript ‘2’ may place it in a grey area, because the law does not protect any derivations of ‘pharmacy’. It would be interesting to observe whether the General Pharmaceutical Council will take legal action when the restaurant opens next year. Perhaps it will be a legal proceeding that will prompt a revision and update of Section 78 of the Act.