Courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery, UK / Features in Forensics: the Anatomy of Crime, Wellcome Collecti

Television programmes, films and books about detectives and forensics have a lingering hold over the British public. Shows such as ‘CSI: Crime scene investigation’ and ‘Silent witness’ capture the imagination with their cutting-edge science and sharp, intelligent characters. Those who are fascinated with death and the processes that help identify ‘whodunnit’ in real life may wish to pay a visit to the new exhibition at the Wellcome Collection in London, ‘Forensics: the anatomy of crime’.

The exhibition is laid out in five rooms, each of which relates to one part of the forensic process: the crime scene; the morgue; the laboratory; the search; and the courtroom. The layout of the exhibition leads you through the investigation from beginning to end, and each room allows the viewer glimpses into the next.

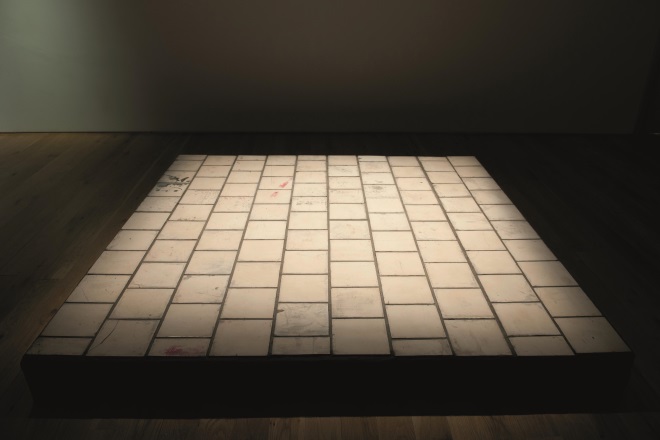

‘The crime scene’ is excellent. The artwork in this room is striking, and includes the reconstruction of an actual crime scene from Teresa Margolles, who lays out the floor tiles on which a friend was murdered. Additionally, a forensic photograph from Angela Strassheim, which uses luminol to show where blood remains at a crime scene in a familial home long after the incident, is strangely compelling.

Source: Artist and Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich / Forensics: the Anatomy of Crime, Wellcome Collection

Teresa Margolles lays out the tiles from the crime scene in which her friend was murdered.

The vital role of entomology is also highlighted in ‘the crime scene’. In September 1935, blowfly larvae were used to help convict a murderer for the first time — the presence of maggots and flies helps to pinpoint the time of death. Environmental factors, such as the temperature of the surroundings and if the body has been placed in a suitcase, can have an impact on the rate of their growth.

Throughout the exhibition, the history of different procedures and artefacts is juxtaposed with pioneering techniques, such as the virtual autopsy, which uses imaging software to reconstruct a corpse without having to cut it open. Where methods or equipment on display have since been updated, a full explanation accompanies the item. For example, a ceramic post mortem table in ‘the morgue’ dates back to 1925 — in modern laboratories, a stainless steel version is used.

Parts of the exhibition are not for the squeamish. In particular, I found the sound recording of a post-mortem examination to be uneasy listening — kudos to you if you can suffer the wet, squishing noise and gentle cracking for more than a minute. I also found the ‘KusÅzu’ sequence of 18th century Japanese watercolours — which, in nine panels, depicts a dead noble woman decomposing — to be quite gruesome.

Source: Wellcome Library, London

One of the panels from the Japanese KusÅzu sequence, which depicts a dead noble woman decomposing.

Videos in each room profile a professional in the relevant field, providing useful insight into the remit of different roles and helping inject emotion into what can seem like a cold, clinical subject. The testimony of Carla Valentine, technical curator at Barts pathology museum, is particularly moving when she describes spending five hours stitching a man together after a train accident so that his family could say goodbye.

The importance of the advent of DNA profiling in criminal investigations is not understated, with many of the experts interviewed in the videos emphasising its role in revolutionising the whole procedure. For me, watching a clip of a researcher sifting through files full of inky fingerprints in order to establish a match drove home how useful these modern systems are.

Scientific information and artefacts are seamlessly combined with artistic representations throughout the exhibition. This seems particularly apt given the role that art plays in real life proceedings, from compiling e-fits of suspects to sketching them in courtrooms. The merging of the two disciplines helps to provide a well rounded glimpse into the emotionally charged but ultimately clinical world of forensic medicine.

The free exhibition is open at the Wellcome Collection, London, until 21 June 2015.