shutterstock.com

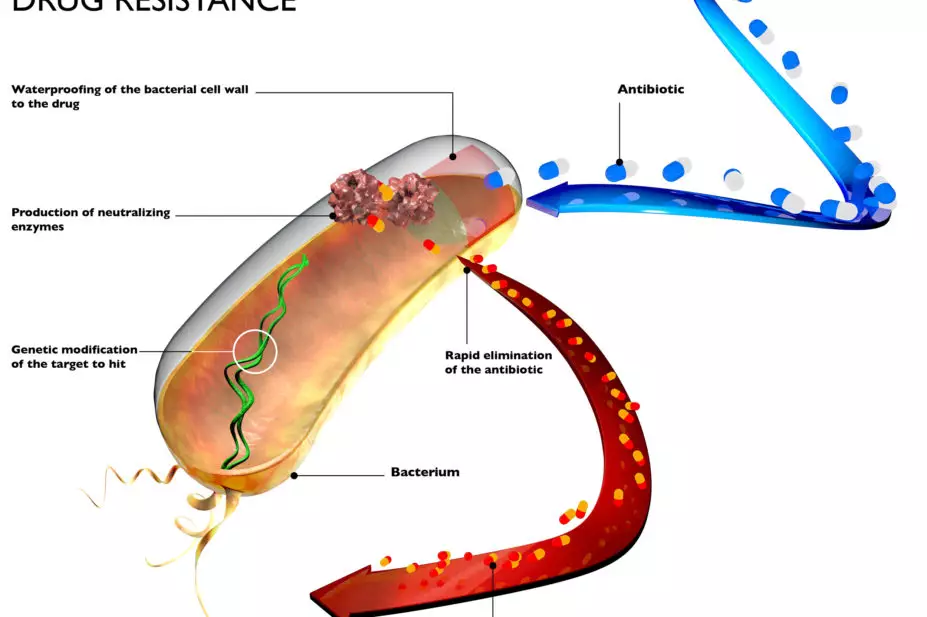

Antimicrobial medicines have revolutionised medical care. However, as pathogens develop resistance to these medicines, the treatment of infections once again can become difficult or even impossible.

While there are no exact figures that capture the true burden of antmicrobial resistance (AMR), estimates show that 700,000 deaths each year can be attributed to the issue[1]

. Antibiotic resistance is a worldwide threat, but is generally higher in many low- and middle-income countries where access to newer, more effective antibiotics is limited[2]

.

Access to effective antimicrobials is needed more urgently than ever by communities around the world. New medicines, especially antibiotics, must be developed to replace those that lose their effectiveness. However, to maintain effectiveness they must be used conservatively, to slow the rise of resistance in the future.

Tackling the problem of AMR demands the concerted efforts of multiple stakeholders, not least national governments, and the role for pharmaceutical companies is clear: to develop new medicines to replace ones that no longer work, make them available and accessible to those who need them, and find new ways to ensure antibiotics are produced and promoted responsibly.

Earlier this year, our team at the Access to Medicine Foundation published the 2020 ‘antimicrobial resistance benchmark’ report, which independently compared how a cross-section of the pharmaceutical industry is responding to the threat of AMR[3]

. The AMR benchmark evaluates company actions and strategies using an analytical framework and metrics designed to assess within three key research areas: research and development (R&D); responsible manufacturing; and appropriate access and stewardship.

We found that while a core group of pharmaceutical companies are making progress in tackling the spread of AMR, change is not happening at the scale needed to radically impact the threat from drug resistance.

Protecting new antibiotics

The AMR benchmark evaluates 30 companies with a major stake in the anti-infectives space, including those with the largest R&D divisions, the largest market presence, and leading expertise in developing critically needed antibiotics and antifungals. The main findings of the 2020 report shed light on how the most important players in the market address the risk of resistance and the global need for appropriate access to antibiotics.

With only a few antibiotics in development, and considering the scale of unmet need, each new antibiotic must be protected at launch by access and stewardship plans. These aim to enable swift access to new products, including in low- and middle-income countries, and to ensure stewardship measures are in place to safeguard appropriate use from day one. The 2020 AMR benchmark found a slight increase in the access and stewardship planning in 2020, albeit from a low base. It identified 32 late-stage candidate antibiotics in development targeting pathogens that pose the highest risk from AMR in the pipelines of the companies in scope. However, only eight of these candidates are equipped with plans to implement both appropriate access and stewardship once they are approved to go on the market.

Advanced planning is shown to improve the speed at which new medicines are made accessible. For example, the biotech company Tetraphase Pharmaceuticals is working with Everest, a China-based biopharmaceutical company, to register its new antibacterial eravacycline in China, receiving the approval for China within one year of gaining market approval in the United States. Eravacycline targets several drug-resistant infections. Access plans need to be integrated with stewardship plans to ensure new products can be used appropriately and remain effective over time.

Sales agents

One of the main drivers for the emergence of AMR is the inappropriate use of antibacterial and antifungal medicines — for example, use when they are not needed, or by use at the wrong dose. When a company offers its sales agents financial incentives to sell a higher volume of products, it increases the risk that products will be promoted inappropriately.

When the AMR benchmark looked into this topic, it found that only a few companies avoid the use of sales agents and reduce the risk of overselling to healthcare professionals. Only one company, Teva Pharmaceuticals, mitigates against this risk by removing the use of sales agents to promote any of its antibacterial or antifungal medicines.

Other companies, namely Otsuka and Johnson & Johnson, apply this stewardship practice to their multidrug-resistant tuberculosis medicines. As another means of mitigating this risk, Cipla, Shionogi and Wockhardt have decoupled sales bonuses from sales volumes, to remove the incentive to oversell their antibacterial and/or antifungal medicines.

Missed opportunities

To reduce the threat of AMR, the right treatment must be used to treat the infection in question. When shortages occur, prescribers often resort to less optimal treatments, which poses an increased risk of AMR.

The AMR benchmark investigated how companies address access to new, on-patent products, as well as access to older antibiotics. It looked specifically at actions to improve access in 102 low- and middle-income countries with a greater burden of infectious disease and higher rates of AMR. Our team found that pharmaceutical companies are missing opportunities to make antibiotics available[3]

.

For new medicines, patent owners or their licensees must register them for sale in a country before they can be made widely available. Out of 13 on-patent antibiotics from the companies evaluated, only three are filed for registration in 10 or more high-burden countries, making it fair to assume that these medicines are not available in dozens of countries in need.

For older antibiotics, our report looked at a group of old but clinically useful medicines known as ‘forgotten antibiotics’[4]

. These medicines can still be used for a broad range of infections, but are either no longer produced or are not being supplied in all countries. This may be because older antibiotics, such as benzylpenicillin and fosfomycin, are not profitable, or because there is a lack of demand, as newer alternatives have become available. The companies assessed in the AMR benchmark are noted to have 24 forgotten antibiotics in their portfolios, but there is only evidence that they are supplying 14 of them to even one country in need of access.

New incentives needed

The need for strict stewardship measures means that high-volume, high-return markets are unlikely to emerge for antibiotics. Pharmaceutical companies therefore have little commercial incentive to commit to the antibiotic market. Our report shows that this is leaving the world precariously reliant on just a handful of pharmaceutical companies to develop and manufacture antibiotics.

Pharmaceutical companies need to stay in the game, invest, develop new medicines, make them accessible and ensure they are produced and promoted responsibly. To do this, these companies need commercial market incentives — also called ‘push’ and ‘pull’ incentives — to drive antimicrobial R&D that targets diseases predominantly affecting vulnerable populations in resource-limited countries. Push incentives subsidise new antibiotic development, while pull incentives financially support and reward companies (post-market) for successfully bringing in new antibiotics to market. Alongside pharmaceutical companies, there is a critical role for all to prevent and control the spread of resistance. While investing in R&D is key, it is also critical to ensure the appropriate use and disposal of medicines, contribute to surveillance, and to strengthen the policies, programmes and implementation of infection prevention and control measures.

Moska Hellamand, researcher; Fatema Rafiqi, research programme manager, Access to Medicine Foundation

References

[1] O’Neill J. Review on Antimicrobial Resistance. 2014. Available at: https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/AMR%20Review%20Paper%20-%20Tackling%20a%20crisis%20for%20the%20health%20and%20wealth%20of%20nations_1.pdf (accessed August 2020)

[2] Klein EY, Tseng KK, Pant S et al. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e001315. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001315

[3] Access to Medicine Foundation. 2020. Available at: https://accesstomedicinefoundation.org/amr-benchmark (accessed August 2020)

[4] Pulcini C, Mohrs S, Beovic B et al. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2017;49(1):98–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.09.029