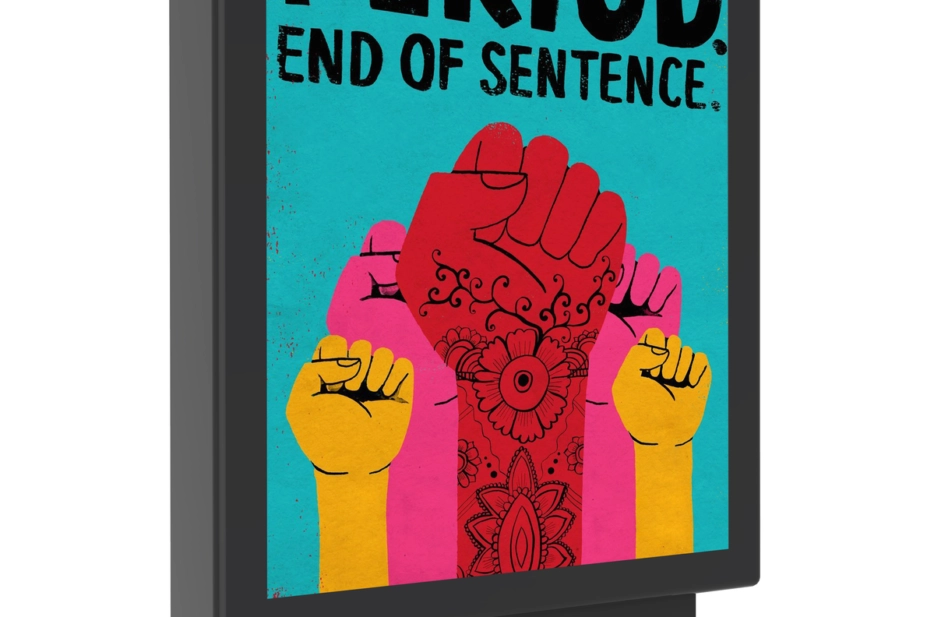

This year, 2019 is the year a short documentary about periods won an Oscar. And deservedly so.

Period. End of Sentence. was directed by Rayka Zehtabchi, an Iranian-American filmmaker. It follows the girls and women of Hapur, India, where discussing menstruation is strictly taboo.

At the very mention of the word ‘period’ in Hapur, girls stifle giggles in embarrassment. An older woman suggests that only God knows why a woman bleeds. Some of the boys are entirely ignorant, asking: “A class period? The kind you’d ring a bell for?”

One young woman, who dropped out of school after she found it increasingly difficult to change her sodden cloth around others, quickly shows how lacking basic hygiene products can preclude girls from education, and keep them locked in subordination.

When we hear how these women are scared to wash or dispose of the rags they use to staunch their bleeds, leaving them vulnerable to infection, it is difficult not to think of the sanitary bins and the sprawling shelves of the UK pharmacy, packed with seemingly endless choice that Western women take for granted. Extra long? Scented? With wings?

Fortunately, ‘Period. End of Sentence.’ never becomes the Coldplay-soundtracked guiltmonger you might expect. At just 26 minutes, it races along — its bouncy score always keeping the piece upbeat. And, importantly, the documentary never patronises or pities.

You are introduced to Sneha, who wants to encourage other women to take control of their periods and, in turn, their ability to work and earn for themselves. She wants to become a police officer; people in her village think she is crazy.

Next, cue Arunachalam, who has invented a machine that allows women to make their own low-cost sanitary pads to use and sell. As he gives a demonstration, it is warming to see the women feeling the simple fluffy white pads — the catalysts for their independence — for the first time.

The women go on to set up a sanitary pad-making unit, working from 9:00 until 17:00, and through electricity outages, if they can. A member of the unit pulls back a cover to reveal boxes containing more than 18,000 sanitary pads. But with the shame of menstruation still so deeply ingrained in society, the women still struggle to go out to shops to buy the products, in fear of the men — and even other women — around them.

So we follow Sneha and her team as they meet with the women of Hapur to directly spread their message and their products, which make big dents in the proverbial wall their society has built around menstruation.

The women’s labours also unexpectedly pique the interest of their husbands, some of whom also become involved: “I made a good pad!”, says a proud local.

While the film is straightforward in its shooting and structure, it packs a powerful punch. “Women are the base of any society”, says one member of the project, and boosting women boosts us all.

The film ends with Sneha sharing her dreams of finding sanitary pads in every store. In the meantime, her wages are funding another dream — her police training.

‘Period. End of Sentence.’ is available for streaming on Netflix, and you can find out more about the project at www.thepadproject.org.

Abigail James

References

Zehtabchi R. Period. End of Sentence. California: Netflix; 2019