Science Photo Library

When I entered the treatment room, I was nervous. But curious.

I thought about the way electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been portrayed by the media over the years. And I wondered if the stigma still surrounding ECT is justified, or had I just blindly accepted it?

ECT isn’t something you’d usually get to observe as a pre-registration pharmacist, so when the opportunity came up during a mental health placement I jumped at the chance. I hoped the experience might challenge my assumptions of the controversial treatment.

In the past, ECT was used to treat multiple psychiatric disorders, but nowadays it is used for severe depressive illness, catatonia, mania and, more rarely, schizophrenia, in patients who do not respond to other treatments or are experiencing severe symptoms.

ECT involves applying electrodes to the side of the head, which deliver an electrical stimulus to create a short-lived seizure. It isn’t fully understood how the treatment works, but a common theory is that it results in an increase in dopamine release, which leads to changes in neurotransmission.

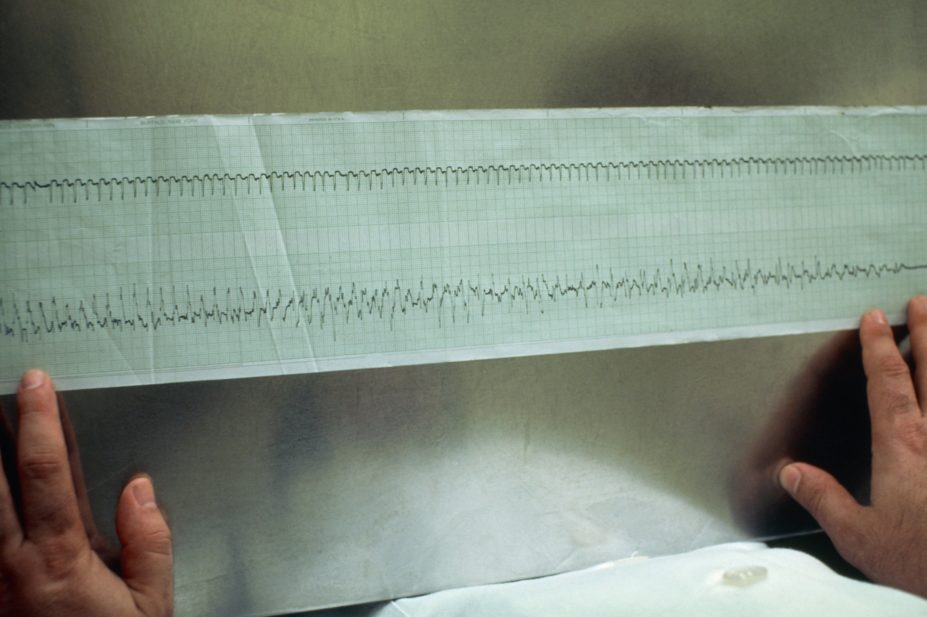

The first patient brought into the room was agitated and nervous, so the team tried to relax her as I was asked to take my place at the end of the bed. I assumed safety might be a concern, but I was surprised to be told the greatest risk to the patient is adverse effects from the anaesthesia. For this reason, the staff carry out continuous monitoring of heart rate, blood pressure and oxygen saturation. To monitor the seizure activity and determine the treatment strength for the next session, electrodes were placed on the patient’s head and body to record an electroencephalogram (EEG).

To ensure a painless and distress-free experience for the patient, the staff use anaesthesia and muscle relaxants. They aim to achieve rapid onset and offset of unconsciousness and muscle relaxation to prevent the patient from having severe and distressing muscle spasms. But as many anaesthetic drugs have anticonvulsant properties, it is important to ensure that there is a balance between ensuring adequate anaesthesia and not reducing the efficacy of the treatment.

Pharmacists have a role to play in ECT too, by advising on medicines management before and after the procedure — the regular medicines the patient takes can interact and affect the treatment’s efficacy. For example, benzodiazepines and drugs with anticonvulsant properties, such as gabapentin, should ideally be held the night before ECT, as these will increase seizure threshold and reduce efficacy. Critical anti-epileptic medications should not be held, but the anaesthetist should be made aware of their use. Like any procedure where anaesthesia is used and a fasting protocol is adopted, management of drugs used for comorbidities — such as diabetes and hypertension — is also important.

Electrode gel was applied and the doctor placed the treatment paddles bilaterally to the side of the patient’s head. The electrical stimulus was administered to the patient and a seizure was induced. This was the part I was most apprehensive to see. I had expected a distressing scene of jolting limbs and a painful grimace; however, much to my surprise, movement was limited to twitching feet and facial muscles as the anaesthesia and muscle relaxant had done their job. After around 30 seconds to 1 minute, the seizure was over and the patient was still once more. Once stable, the patient was moved to the recovery room, and the next ECT patient was brought in and the process repeated.

After the end of the next patient’s ECT session, we visited the first patient in the recovery room. Around an hour had passed since we had seen her and, as the curtain was pulled back, I was amazed to see her sitting up in bed, calmly chatting while eating toast.

The consultant explained that although ECT has been used for decades, it is still an effective therapy for many patients who don’t respond to other treatments. And, as we could see with this patient, the benefits were clearly visible. However, there are patient cases where side effects, such as memory loss, can limit the stimulus dose and reduce treatment efficacy, and, in severe cases, prevent its use.

This experience opened my eyes to the reality of ECT. Naively, I had expected to witness an unsafe and painful treatment. Where were the distressed, jolting or zombie-like patients? I saw only a safe and dignified treatment, and we must abolish the stigma surrounding it. Sometimes you need to seek out the reality for yourself.

Kaley Dickerson, pre-registration hospital pharmacist, North West Anglia NHS Foundation Trust