American College of Neuropsychopharmacology

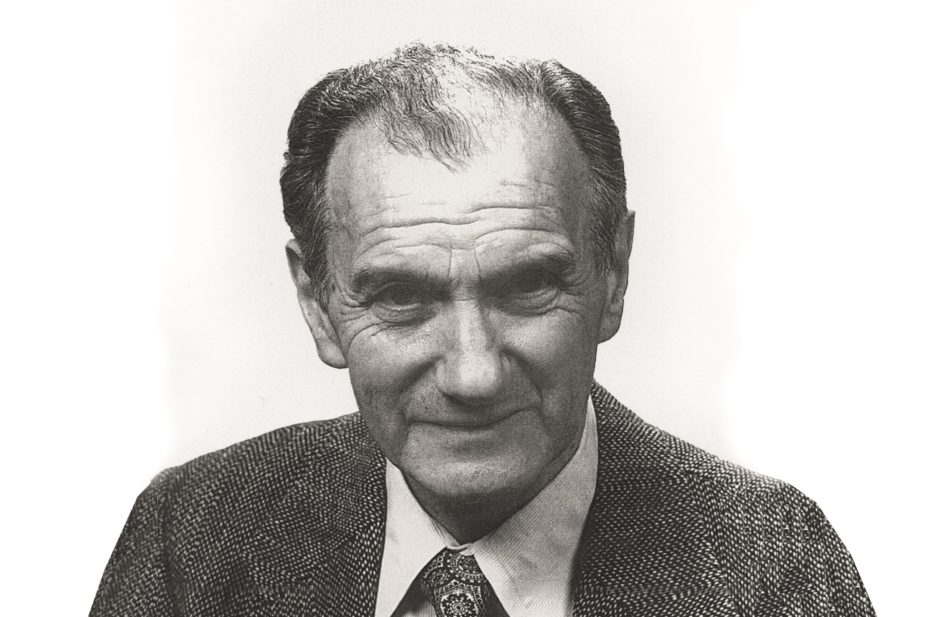

Joel Elkes, a pioneer of neuropsychopharmacology who has died aged 101 in Sarasota, Florida, carried out landmark research on the drug chlorpromazine.

In 1953, as professor of experimental psychiatry at the University of Birmingham, he conducted a small controlled trial of the drug, which had been discovered by the French company Rhone-Poulenc in 1950. Organised with his then wife, Charmian Elkes, clinical research fellow at the University of Birmingham, the study was designed to test the effect of chlorpromazine on chronically overactive psychotic patients. The drug and inert control tablets were given to the same patient in alternating periods[1]

. The study of 27 patients, 10 of whom had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, showed definite improvements in 7 patients and slight improvements in a further 11 patients.

“To the question whether the drug may be useful in the management of the chronically overactive psychotic would appear to be a qualified ‘yes’,” the authors concluded. In the group showing the greatest improvements “patients became less tense and less disturbed by their hallucinations and delusions during the weeks they were receiving chlorpromazine. Their eating, sleep and social habits changed for the better,” the authors noted.

An editorial in the issue of The BMJ carrying the study report said: “The well designed experiment by Elkes and Elkes in which every patient was made to serve as his own control provides definite evidence that the drug is of benefit.”

“This was a revolution in treatment without a shadow of doubt,” said Chitra Mohan, associate medical director of the Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health Foundation Trust. “Before this the only treatments for these patients had been insulin, shock therapy, electroconvulsive therapy and lobotomies.”

Thomas Ban, emeritus professor of psychiatry at Vanderbilt University, Tennessee, has said the success of the drug was instrumental in reintegrating psychiatry with other medical disciplines. “It turned psychiatrists from caregivers to fully fledged physicians who can help their patients and not only listen to their problems[2]

.”

Elkes was born into a Jewish family in Konigsberg, Prussia, on 12 November 1913. He spent his first five years in Russia where his father, Elkhanan Elkes, was a doctor in the Russian Army during the 1914–1918 war. In 1918, the family moved to Kovno, Lithuania, where Elkes attended secondary school and developed a particular interest in physics.

Before chlorpromazine the only treatments for these patients had been insulin, shock therapy, electroconvulsive therapy and lobotomies

In 1931, he left Kovno for London with a letter of recommendation from the British Ambassador to Lithuania, a friend of his father’s, to study medicine at St Mary’s Hospital in Paddington. There he found himself “extraordinarily fortunate”, taught bacteriology by Alexander Fleming, who discovered penicillin, and medicine by Charles Wilson — later Lord Moran, physician to Sir Winston Churchill. Attending a meeting of the British Physiological Society, demonstrating the firing of neurons “made me determined to get into the nervous system come what may[3]

”.

“As a medical student at St Mary’s Hospital, London, in the 1930s, I was deeply attracted to psychiatry. However, the excellent lectures and demonstrations in the local mental hospital left me bewildered, curious and hungry, and groping for a physiology and chemistry which, at the time, did not exist,” he said in an article in an e-book prepared for his 100th birthday[4]

.

While fascinated by his studies, this was a difficult period. With the outbreak of war Elkes was cut off from financial support from his father. Jewish people in Kovno were forced into a ghetto where Elkhanan was elected leader. In 1944 he and his wife were sent to concentration camps; he died in Dachau but his wife and Elkes’ mother, Miriam, survived and later went to Israel.

Elkes graduated in 1941 and was invited to the University of Birmingham to establish a department of pharmacology. “Vast questions beckoned everywhere. I felt like a naturalist advancing into a strange country,” he said.

He married Charmian Bourne, a GP, in 1944. Their only child, Anna, was born in 1946. In 1951, he was appointed head of the department of experimental psychiatry at the University of Birmingham. “What attracted me to research in psychiatry was an urge to leave the bench and get to people,” he said. In 1957, he was invited to the United States to create a clinical neuropharmacology centre at the National Institute of Mental Health, based at St Elizabeth’s Hospital, Washington DC.

Between 1963 and 1975, he was professor of psychiatry and behavioural sciences at John Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. He later helped establish a psychopharmacology programme at McMaster University in Ontario, Canada, and, with his second wife Josephine Rhodes, helped set up a centre for chronic illness in Louisville, Kentucky.

A keen painter in later life, “Gardens of the mind”, a retrospective exhibition of his works, was opened in Sarasota in September 2015. He died on 30 October 2015.

Elkes is survived by his daughter Anna from his first marriage and his third wife Sally Lucke-Elwes. His second wife Josephine Rhodes predeceased him.

References

[1] Elkes J, Elkes C. Effect of chlorpromazine on the behaviour of chronically overactive psychotic patients. BMJ 1954;2:560–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4887.560

[2] Ban TA. Fifty years chlorpromazine: a historical perspective. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2007;3:495–500. PMCID: PMC2655089

[3] Elkes J. Psychopharmacology: finding one’s way. Neuropsychopharmacology 1995;12:93–111. doi:10.1016/0893-133X(93)00017-G

[4] International Network for the History of Neuropsychopharmacology. Celebration of the 100 years birthday of Joel Elkes. 2013.

You may also be interested in

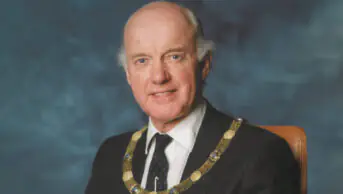

Philip Leon Marshall Davies (1938–2026)

Bill Scott OBE (1949–2025)