Mclean/Shutterstock.com

In drug misuse, there are issues at both ends of the scale: there are people not taking substances when they should, and people using substances they shouldn’t.

It’s tight regulation and licensing that differentiate a medication (used to promote health) from a drug (a potentially dangerous unregulated substance), and this protects the public from harm. But some members of the public, whatever their demographic, may be unfamiliar with this way of looking at drugs.

Evidence suggests that beliefs about medication are constructed from information and experiences from a person’s environment[1]

. This social meaning can be shaped by many aspects of culture, including the internet, art, literature and music.

Music, particularly, has been shown to contribute to beliefs about identity in older adults, and pharmaceutical use is well evidenced in this medium[2],[3]

. In music, pharmaceutically active products are used to project musicians’ identities, express feelings and signal virtues.

Existing literature would suggest that illicit drug use tends to be the focus of pharmaceutical appearances in music; however, contrary to this thinking, legitimate medications are also often referred to[4]

.

Finding out more about how these medications and drugs are perceived, through music, could help us to understand more about our patients and improve their outcomes.

Music’s influence

Musical references to medication and drugs used illicitly in music may not directly influence listeners’ behaviour, but limited evidence from the United States (there are also limited UK data) suggests increased exposure to references to medication or drug use makes changes in behaviour more likely.

For instance, one study at a US university collected self-reported information about music preferences, substance use and demographic characteristics from 2,349 students[5]

. It showed that those who listen to rap, hip-hop or alternative rock — which contain more references to drugs than other musical genres — were more likely to report use[5]

. This may be concerning since, in 2008, top music sales data suggested that the average adolescent listener in the US was exposed to 84 references of illicit substance use per day[6]

.

Drug references through music streaming

But very little work has examined musical references that relate to both medication and drug use, particularly within the context of modern music consumption — which has changed considerably since 2008, with more and more listeners choosing to stream music, rather than purchase it. We, therefore, sought to explore how pharmaceutical products are referred to in contemporary music accessed through streaming services.

Like other researchers investigating this idea, we sought to collect a convenience sample of rap, hip-hop, R&B and pop. The sample means not to be strictly representative, but rather provides us insights into a new area of research, which will support further, and more representative, sampling. Music was streamed on Apple Music over an eight-week period, to mirror how users of this service would typically listen to music. No songs were excluded. Music was listened to for approximately 2 hours per day for 8 weeks, and around 2,240 songs were listened to over this period.

Among the songs that were listened to over the study period, 4.8% (n=107) made references to medication or drug use. These included songs that had both single and multiple references to medications or drugs. We found that most references were to illicit drug substances (4.3%, n=97), rather than medications (0.3%, n=7). You can listen some songs from our sample through Apple Music or Spotify below.

Legitimate medication or illegal substance?

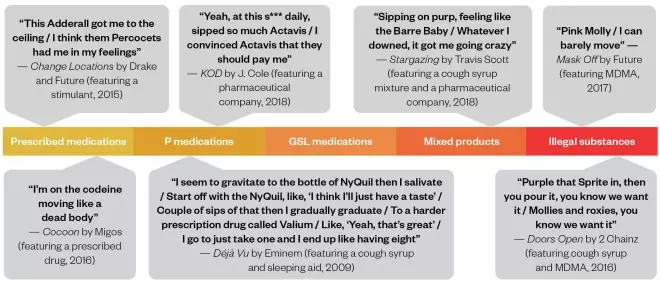

A key finding was a sliding scale of references to products, including prescribed medication at one end and illicit substances at the other; the use of nicknames meant it was not always clear if the references were to medications (prescription only, pharmacy-only or general sales list) and illicit drugs, or a mixture of both (see Figure). References were often to legitimate medications being used illegitimately or being mixed with other products to create new substances. For example, some musicians refer to a product called ‘lean’ or ‘purple drank’: a drink that requires users to mix codeine and promethazine cough syrup, both legitimate medications, with fizzy drinks, sweets or alcohol to create a new illicit drug substance[7]

.

Figure: Sliding scale of pharmaceutical references in contemporary music

Drug nicknames

Additionally, references used nicknames, street names or abbreviations for both medications and drugs. For example, terms such as ‘bean’ and ‘molly’ are slang for MDMA mixed with other legal and illegal products. But ‘roxies’ is an abbreviation for roxicodone, while ‘oxy’ is the abbreviated version of oxycodone.

Substances were also identified by references to the name of the pharmaceutical company, instead of the drug itself. For instance, ‘Act’ is the abbreviated name for Actavis — a pharmaceutical manufacturer. Both Actavis and Barre Pharmaceutics were used as references to promethazine codeine syrup, which is used to make lean or purple drank. The similar approaches to naming drugs and medications meant references blurred the boundary between medication and drugs for those referring to them, and perhaps, in turn, those listening.

Strong emotional connotations

References to both medications and drugs inferred extreme emotions. For example, using addictive substances (such as morphine, nicotine, cocaine, MDMA and heroin) were a metaphor for being in love.

Other references, such as those to codeine, Xanax (alprazolam) and Advil (ibuprofen), inferred negativity, weakness, sadness and death; while the use of illicit substances, such as cocaine powder, was associated with positive and strong emotions that prevented sadness.

These ideas reinforce the suggestion that pharmacologically active substances are also socially active substances; their very name can infer meaning, context and feelings between musicians and listeners.

There’s still work to do

Here, music is shown to be a rich source of information and misinformation about drugs and medications, which is easily accessible when listening to music as part of everyday life. It shows that our understanding of how medications and drugs are represented, as different and discrete entities, may be outdated and not align with the general public’s perspective of drug and medication use.

From opioids (such as codeine and ketamine) to cough syrups (such as promethazine), as well as analgesics, benzodiazepines and amphetamines, the range of medications referenced alongside illicit drugs (such as MDMA and heroin) is large. This is concerning, given that existing literature indicates that people who listen to music with references to drug use may be more likely to use these substances at least once in their life[5]

.

Yet there is very little work determining the impact that musical references to medications may have on the acceptability of medications, treatment adherence, and whether this contributes to a misunderstanding and poor use of medications.

Further research is needed to ensure pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals, understand how patients could be exposed to information (and misinformation) about medications and drugs through social and cultural platforms.

Radin Karimi, pharmacy student, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Newcastle University

Adam Pattison Rathbone, lecturer, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Newcastle University

Apple Music has been contacted for comment.

References

[1] Rathbone AP, Jamie K, Todd A et al. J Clin Pharm Ther 2020. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.13288

[2] Dabback WM. Action, Criticism and Theory for Music Education 2010;9(2)60−69. ISSN: ISSN-1545-4517

[3] Taylor S. Probation Journal 2008;55(4):369−387. doi: 10.1177/0264550508096493

[4] Lee JP, Battle RS, Soller B et al. Addict Res Theory 2011;19(6):528–541. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2010.545156

[5] Hart M, Agnich Chavez L, Stogner J et al. American Journal of Criminal Justice 2014;39(1). doi: 10.1007/s12103-013-9213-7

[6] Primack BA, Dalton MA, Carroll MV et al. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2008;162(2):169−175. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.27

[7] Peters R, Yacoubian GS, Rhodes W et al. J Psychoactive Drugs 2007;39(3):277−282. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2007.10400614