PA Images

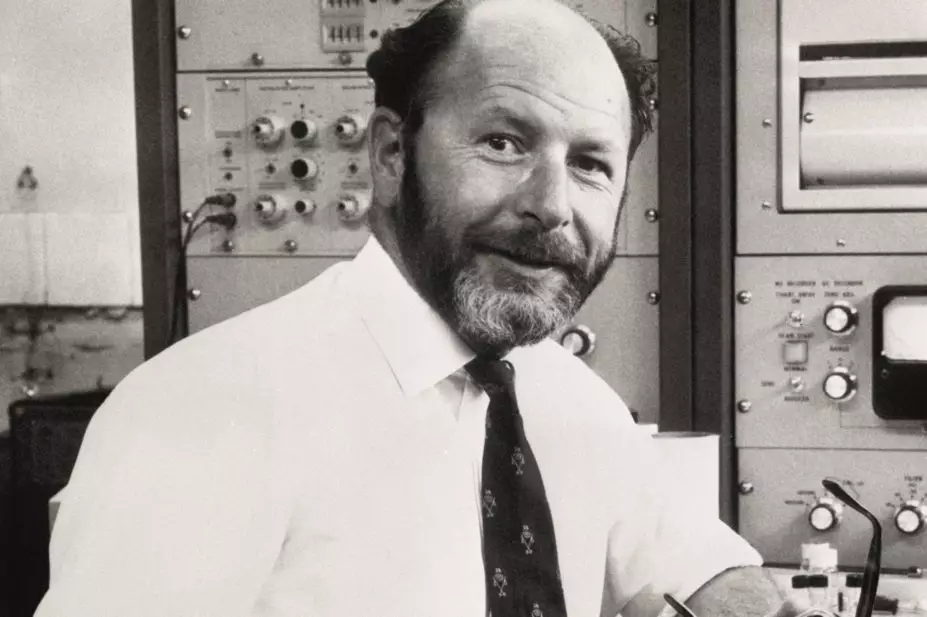

Merton Sandler, a pioneer in psychopharmacology, first proposed a link between depression and a deficiency in monoamines, and his research eventually led to the development of modern-day antidepressants.

He did not originally set out to become a researcher but early experiments left him with a lifelong passion. “In 1949, I qualified as a young medical doctor and was swept off my feet — figuratively speaking — by investigative medicine, which I found to be a sort of grown ups’ adventure playground,” he said.

He remained keen that others should share the enjoyment. “Merton always pursued a collaborative rather than competitive approach and made work fun,” said Vivette Glover, professor of perinatal psychobiology at Imperial College London, who worked with Sandler for 20 years. “There was almost nothing that did not interest him and he made a point of talking to everyone in the lab — 20 of us — every day. We used to call these his ward rounds,” she said. Glover also recalls being required to drink red wine early one morning, while other lab staff downed vodka, to test Sandler’s hypothesis that red wine was a trigger for migraine. His later work went on to prove his belief.

Interviewed at the 1998 conference of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, Sandler said: “My whole career has been shaped by expediency and opportunism and the jobs that were available.”

Sandler, who has died of cancer, aged 88, was born into an observant Jewish family in Manchester and won a scholarship to Manchester Grammar School, which he hated, before studying medicine at the University of Manchester. After qualification he joined the Royal Army Medical Corps where he was given a laboratory. In 1953, he and Michael Pare, another doctor soldier, had their results published in The Lancet.

After leaving the army, Sandler became a research fellow at the Brompton Hospital, then senior lecturer in pathology at the Royal Free Hospital medical school. Between 1973 and 1991, he was professor of clinical pathology at the University of London.

In 1956, he and Pare suggested that depression was caused by a deficiency of monoamines in the brain, and their research showed that depression and migraine were responsive to drug treatment. In the early days he had no hesitation about experimenting on himself. He took riserpine intravenously and described how it made him — a normally calm man — aggressive towards his wife, Lorna. “My nose became blocked and I became mildly psychotic for about a month,” he recalled. He also gave volunteers lysergic acid diethylamide to see if those pretreated with a 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor precursor might suppress the schizophrenia-like symptoms normally associated with LSD. “We couldn’t carry on because the sixth volunteer was a disaster; he had a bad trip on LSD and had to be held down by male nurses and tranquillised,” Sandler recalled. “He only came back to sanity after about six months, if he ever did. In those days there were no ethical committees to pronounce on our experimental design. It was not uncommon for experimentalists to test new drugs on themselves.”

He would later go on to work on migraine, which he suffered himself and, as an impoverished medical student, once had to lie down inside the Folies Bergère, a cabaret music hall located in Paris, because of an attack. He was convinced that the causes of migraine were chemical despite the view, prevalent at the time, that “migraine was something neurotic that a rather hysterical cousin called Dorothy had”.

Sandler published some 700 papers and wrote books on wine, sexual behaviour, aggression and psychiatric humour.

Working with the neurologist Gerald Stern, he did research suggesting that the monamine deprenyl could be helpful in the treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. Deprenyl was not legal in the UK at the time so Sandler went to Hungary and smuggled some in, past British customs: “I flew to Budapest in my flasher’s mac — a mackintosh with large pockets. I collected two large polythene bags of white powder and walked boldly through British customs. Nobody stopped me and fortunately the sniffer dogs were on holiday,” he said. “I hate to think what would have happened if I had been caught.”

“We told the Committee on Safety of Medicines and they were quite decent about it. They said we wouldn’t be prosecuted and could go ahead and publish,” said Sandler.

He also carried out research on prisoners at Wormwood Scrubs on the effects of amphetamine psychosis. Access was denied when the press got hold of the story but after Sandler met Norman Fowler, then transport secretary (and later health secretary), at a dinner party, the prison gates were opened once more. “It is nice to have influence,” Sandler remarked.

You may also be interested in

Bill Scott OBE (1949–2025)

David Taylor (1946–2025)