Courtesy of Shane Kailla

I have been interested in experiencing pharmacy practice abroad since I began studying pharmacy. During my third year of study I researched companies that help students find overseas placements. I was interested in China because of its growing pharmaceutical sector, and I applied to CRCC Asia because it offered internships in the healthcare sector. The application was a simple process which involved a telephone interview, and I highlighted my interest in hospital pharmacy. Shortly after, I was invited to the Shanghai Jiao Tong University Affiliated First People’s Hospital for a one-month internship, which was partly funded by the University of Birmingham, where I am studying. On the placement, I shadowed the hospital’s clinical pharmacists and doctors.

Throughout my time in China it was clear that an increasing number of people were choosing to use western medicine over traditional Chinese treatments, and I had the chance to experience an entirely different healthcare system.

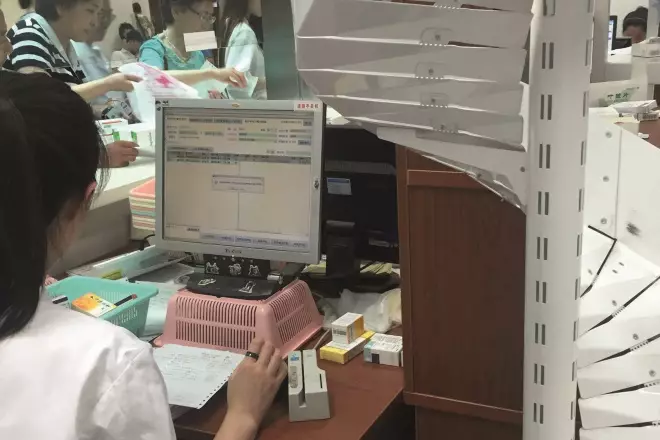

Clinical pharmacy, which is ward based, is seen as a different profession from dispensary-based pharmacy. On my first day I was given a tour of the outpatient pharmacy, which is separate from the inpatient and emergency pharmacy. There are 12 windows through which patients see a pharmacist, who processes prescriptions and uses robots to select the medicines. However, there is no counselling or proper checking procedure involved — it was just about processing prescriptions. This is highlighted by the vast number of prescriptions they handle, approximately 10,000 a day from outpatients alone.

Health services and policy

I came across many interesting policies while shadowing the medical professionals. There was no apparent smoking cessation policy in place. I was told that attempts were made to reduce the number of smokers. However, it proved to be ineffective and further attempts were subsequently abandoned. It appears that there are no programmes for treating drug addiction like we have in the UK. Instead, addicts are often imprisoned rather than given treatment. As well as this, HIV is heavily stigmatised and it is seen as a great shame to be HIV positive.

On a more positive note, the hospital runs a modern organ transplant service. Due to the large population, there are inevitably more deaths, meaning more potential organs are available for transplants. I met a 13-year-old patient with Wilson’s disease — a disorder in which you have a higher than normal amount of copper in your body — who was receiving a liver transplant. However, potential close matches, such as from siblings, are non-existent, owing to the one-child policy in parts of China, which complicates the service. Despite this, the average waiting time for an organ transplant is only around three months. Treatment, however, is not covered by insurance and a liver transplant can cost up to £60,000.

The hospital also had a policy relating to overprescribing of antibiotics. If a ward is found to be overusing antibiotics, doctors will face a fine, deducted directly from their monthly pay.

Source: Shane Kailla

Medication administration is also different. A QR code is assigned to each patient, and their prescription and dose of medicine also carries this QR code. Each dose is supplied from the inpatient pharmacy and labelled with the QR code. When nurses administer the medicine, the QR code of the patient and dose is scanned to ensure they match. Administration can only occur if the codes match. This technology is currently not available on the NHS but has the potential to make the way medicines are administered in hospital safer.

Culture

I had culture shock in China — for me, perhaps the biggest difference when working there is in social behaviour. Mian zi, the concept of face, which refers to social status, propriety, prestige or a combination of all three, is held closely to each individual in China. Gaining or giving face (gei mianzi) by giving or receiving compliments boosts your reputation and increases the positive perception your colleagues have of you. However, losing face, through disagreements and public displays of anger or aggression, is seen as highly negative and can jeopardise your relationships with both colleagues and patients. When addressing colleagues it is important to use their professional title as a sign of respect. These cultural elements of China should always be adhered to in order to build relationships with colleagues. The Chinese people believe in the idea of becoming friends before working together.

The difference in culture of China was stark, but I also found the Chinese to be very friendly. Colleagues frequently offered to take me out for lunch or dinner. Here, however, it is tradition that the highest ranking professional pays for your meal — offering to pay could be seen as disrespectful. Finishing everything on your plate is also seen as impolite because it gives the impression that you are not yet full! Even seating arrangements when attending meals are important. The highest ranking professional occupies the seat facing towards the restaurant door and the lowest ranking person sits with their back to the door.

Although the culture may be different, fully immersing yourself in an unfamiliar country is the only way to appreciate its true values. Living and working in China was the highlight of my year and offered me an unrivaled experience of working outside my comfort zone. I highly recommend such opportunities to fellow students.