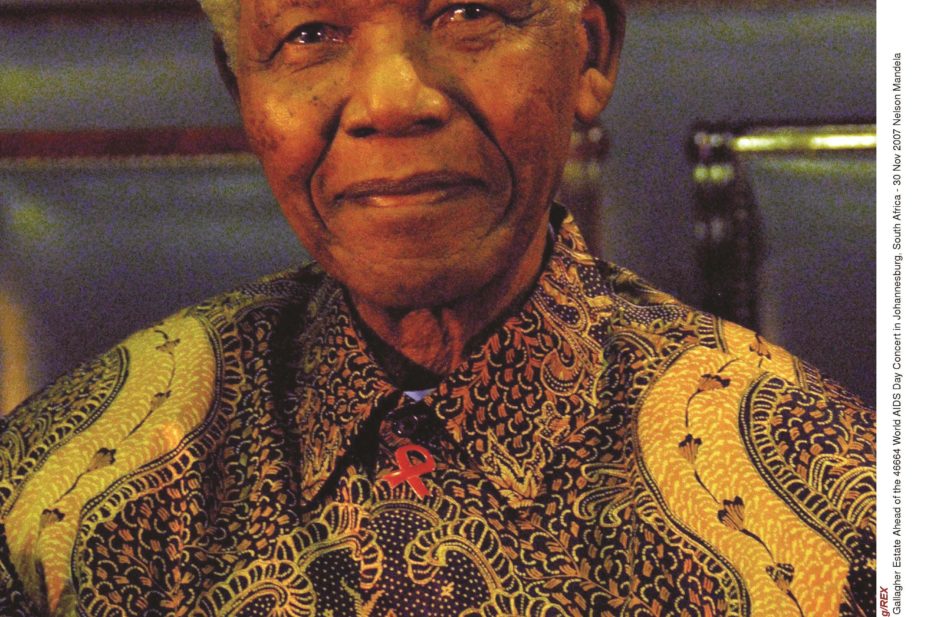

Rochard Young/Rex

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was born in 1918. From humble beginnings in a small Eastern Cape village, he became the father of the rainbow nation of post-apartheid South Africa.

The name given to him at birth, Rolihlahla, colloquially means “troublemaker”, which is how many white South Africans viewed him when he became an anti-apartheid revolutionary. After serving 27 hard years as a political prisoner, he emerged from prison to become the first president of a democratically elected government in an election that gave universal franchise to all citizens.

He became widely revered as a statesman and peacemaker, which earned him the fond nickname of “Tata”, an isiXhosa word that means father. He is also widely referred to as “Madiba”, which is his clan name, and refers to his ancestral descent.

Transition

The transition from a country in turmoil to a country striving to correct the inequities and iniquities of the past was not easy. As its president, Madiba was very aware of the abject poverty, lack of housing and hopelessly inadequate education of many of its citizens. He firmly believed that education was the key to progress: “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.”

Even before he became president of the country, he spoke about the fact that HIV/AIDS in South Africa is not merely a medical condition, but an indicator of the serious socio-economic challenges that people face. It is a grim reminder that apartheid’s legacy needs to be redressed.

In 1953 his presidential address to the African National Congress Transvaal congress contained a sombre health warning: “Because of lack of proper medical amenities our people are ravaged by such dreaded diseases as tuberculosis, venereal disease, leprosy [and] pellagra, and infantile mortality is very high.” Regrettably South Africa still battles with tuberculosis, sexually transmitted infections, malnutrition and high infant and child mortality. In 1988, Mandela contracted tuberculosis. In those days, before drug-resistant TB had emerged, it was successfully treated but it damaged his lungs and left him susceptible to recurrent infections. The incident made him well aware of the importance of following the complete treatment regimen.

Passion and compassion marked Tata’s relationship with children. In his private capacity, he became a philanthropist of note, starting the Nelson Mandela Children’s Foundation in 1995. This is a charitable organisation with the motto “Changing the way society treats its children and youth”.

It is therefore not surprising that one of the areas that he supported fully in the healthcare arena is that of immunisation. In launching the “Kick polio out of Africa” campaign in 1996, he said: “The legacy of our colonial past, lack of resources and the devastation of war have rendered our children especially vulnerable to disease.” He was highly aware of the fact that a campaign such as this could not be accomplished overnight, and he urged the country to continue multiplying the momentum of the campaign in order to reach every child in Africa.

Challenges

In August 1994, after 100 days in the presidential office, Mr Mandela opened the budget debate in Parliament by highlighting the challenges that needed to be faced by the new government. His speech included a reference to AIDS. “We have also allocated funds for an expanded AIDS awareness and prevention campaign. The obvious must be stated over and over again: this epidemic has major social and economic implications for our nation and must be addressed with urgency,” he said.Sadly, the AIDS denialism that characterised the Mbeki government left an impermeable stain on the AIDS pandemic in South Africa.

Mr Mandela’s attitude to HIV and AIDS was very different. Having seen the plight of AIDS orphans, he actively encouraged more extensive campaigns on prevention and treatment, as well as research into vaccines. In 2005, his son died. In announcing the cause of death, Madiba said: “Let us give publicity to HIV/AIDS and not hide it, because the only way to make it appear like a normal illness like tuberculosis, like cancer, is always to come out and say somebody has died because of HIV/AIDS, and people will stop regarding it as something extraordinary.”

During Mr Mandela’s tenure as president, the Patient’s Rights Charter (one of the first in Africa) and the National Drug Policy (1996), among others, were developed. However, the latter, like many good policies South Africa has, was not fully implemented. It has not been revised since then.

At the time of his death, South Africa went into mourning for the elder statesman. We were privileged to have the benefit of his wisdom for so long. No one can deny that, in our hour of deepest need, the saying “cometh the hour cometh the man” resonated with truth.

Hills to climb

Tata Madiba, you were our man, and we will endeavour to carry your legacy forward. Our beloved nation still has a long walk to freedom ahead. As you so rightly said: “After climbing a great hill, one only finds that there are many more hills to climb.” We will walk the road with pride and determination, as you did. (We can start by making his dream of a children’s hospital a reality by contributing to its funding.)

Although there will never be another Madiba, we now need a similar champion for non-communicable diseases which are increasingly becoming pandemics in our country and, indeed, in the world, especially in developing countries.

Rest in peace, Tata.