Shutterstock.com

One man was so certain the May 2015 general election would result in a hung parliament that he bet a record £200,000 on the outcome. Not a safe bet. Widely touted in the media as one of the most unpredictable elections, the Conservative Party exceeded expectations, opinion polls and even the exit polls to win a majority of seats and form a new government.

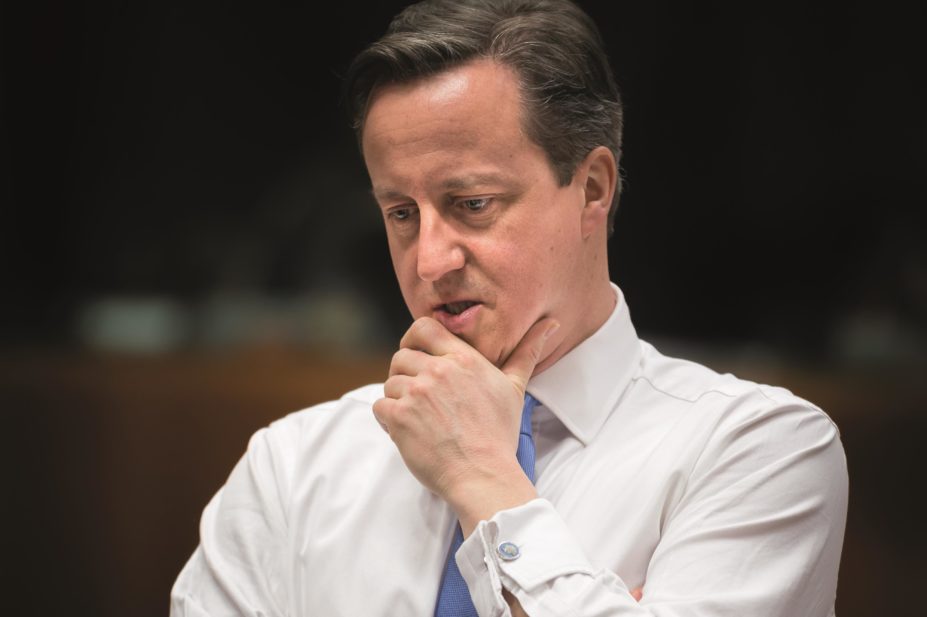

In England, the Conservative-only government inherits an NHS of its own design. And Jeremy Hunt, who continues in the position of health secretary, has his work cut out in keeping healthcare services afloat. In a major post-election speech, prime minister David Cameron reiterated his ambitions for “a truly seven-day NHS”, although this may only serve to exacerbate the known funding gaps within the service.

The Tories pledged in their election manifesto to find an additional £8bn required to deliver the NHS Five Year Forward View — a roadmap for change published by NHS England in October 2014. Yet this is the minimum additional money identified by the national commissioning board to keep the NHS running each year by 2020–2021, on the assumption that a whopping 2–3% in efficiency savings can be made annually. This may be unrealistic; it’s double the rate of savings achieved by the NHS in recent years, and much of that was delivered by freezing public sector pay. NHS England has projected the annual shortfall to be £30bn if no efficiency savings are realised.

The

new government should take a pragmatic view of how far the proffered £8bn will stretch. Moreover, it must be transparent about where the money will come from. In the countdown to the general election, the chancellor George Osbor

ne claime

d he had “a balanced plan”, but would not elaborate on which, if any, public services would need to be sacrificed to fund

the Tories’ NHS promise.

The government should be cautious because further cuts to public services, already under the cosh through five years of austerity politics, could have unintended consequences for the health and well-being of the population, especially vulnerable groups. This could add to the burden on NHS services in the years to come, although this would be tough to measure.

The NHS Five Year Forward View calls for greater integration between health and social care, and a “radical upgrade” in prevention and public health. Yet the Health and Social Care Act 2012, the brainchild of previous health secretary Andrew Lansley, has done little to enable a joined-up approach to services, despite what the law’s title might suggest. NHS organisations now sit within a labyrinthine structure that has caused confusion and blurred the lines of communication and accountability. Social care remains the responsibility of local authorities, which also took over public health budgets on 1 April 2013.

Annual budgets and each player’s responsibility to balance their own books remain barriers to collaboration. Social care budgets have not been promised the same protection as healthcare by the Conservatives. Real steps towards integrated services for patients and the public would require a pooling of resources and some form of central coordination. We look forward to seeing how the Manchester experiment — devolution of £6bn health and social care funding to Greater Manchester statutory organisations — plays out over the coming years.

For now, Cameron must make good on his funding promises, and leave health and care organisations room to manoeuvre, somehow, without political meddling.

You may also be interested in

Tackling the NHS drug budget: why we set up a regional collaboration for medicines value

Lack of joined-up working between pharmacy and general practice is ‘nonsensical’, says former BMA chair