Nic Bunce / Clinical Pharmacist

Clinical guidelines help healthcare professionals and patients make appropriate healthcare decisions[1]

. With the proliferation of guidelines and position statements for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), generalist front-line clinicians need more prescriptive advice on the most appropriate therapeutic options for individual patients.

The main clinical guidelines for T2DM used in the UK are:

- ‘Type 2 diabetes in adults: management’ (NG28) from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), last updated in 2017;

- ‘Pharmacological management of glycaemic control in people with type 2 diabetes’ from the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), published in 2017;

- ‘Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes’ — a consensus report from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), published in 2018.

When guidelines are used uniformly across the population, evidence-based medicine is translated into clinical practice: care is cost-effectively standardised across the healthcare system to facilitate consistent and effective practice, which improves health outcomes for patients. But quantitative and qualitative studies have shown wide variation in adherence to T2DM guidelines[2]

— so how clinically applicable are these guidelines in practice?

Guidance from England and Wales

The most commonly used guideline for T2DM in England and Wales is NG28[3]

. It recommends reinforcing advice on diet, lifestyle and adherence to drug treatment, and agreeing an individualised HbA1c target based on the person’s needs and circumstances (including preferences, comorbidities, risks from polypharmacy and tight blood glucose control, and the ability to achieve longer-term risk-reduction benefits).

However, the central theme of NG28 lies in the attainment of glycaemic targets for people with T2DM, with a preference for antidiabetic drugs with the lowest acquisition cost. The pharmacological recommendations of the algorithm — after failure of lifestyle interventions — begin with patients who can tolerate metformin. Recommendations are made for the addition of metformin if HbA1c rises above 48mmol/mol (6.5%). Further intensifications are advised with various oral agents if HbA1c rises above the set target of 58mmol/mol (7.5%). The sequential additions of various agents are recommended if patients do not achieve the HbA1c targets in a timely manner (six months). There is some merit in the focus on HbA1c control — there is evidence that patients who know their HbA1c levels are more likely to achieve control[4]

— but less than half of patients with diabetes are aware of their HbA1c levels. Therefore, starting a diabetes consultation with a patient using the central theme of glycaemic control, as proposed by NG28, is likely to be ineffective for these patients. NG28’s approach to diabetes control, with a focus on adding more and more medicines if HbA1c is not on target, is not individualised to the patient.

Guidance from Scotland

The guidance for managing glycaemic control in people with T2DM from SIGN (SIGN 154)[5]

was developed as a rapid update using evidence from five sources, including NG28. The SIGN guideline acts as a companion to the revised Scottish diabetes prescribing strategy ‘Quality prescribing for diabetes: A guide for improvement 2018–2021’[6]

.

In SIGN 154, several dimensions have been specified in addition to the achievement of glycaemic targets. The algorithm highlights the need to consider various characteristics of the drugs used in the management of patients with T2DM. Properties listed are efficacy, hypoglycaemia, weight, indication for use in chronic kidney disease and, most importantly, proven cardiovascular benefits. The guideline specifically mentions the use of sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP1) receptor agonists, which have proven cardiovascular benefits in people with diabetes and established cardiovascular disease.

SIGN 154’s focus on various properties of the drugs, together with the achievements of HbA1c targets and various patient characteristics, makes the guideline more functional.

American–European agreement

The publication of the ADA–EASD consensus report in 2018 finally brought comprehensive, patient-centred guidance on the management of T2DM[7]

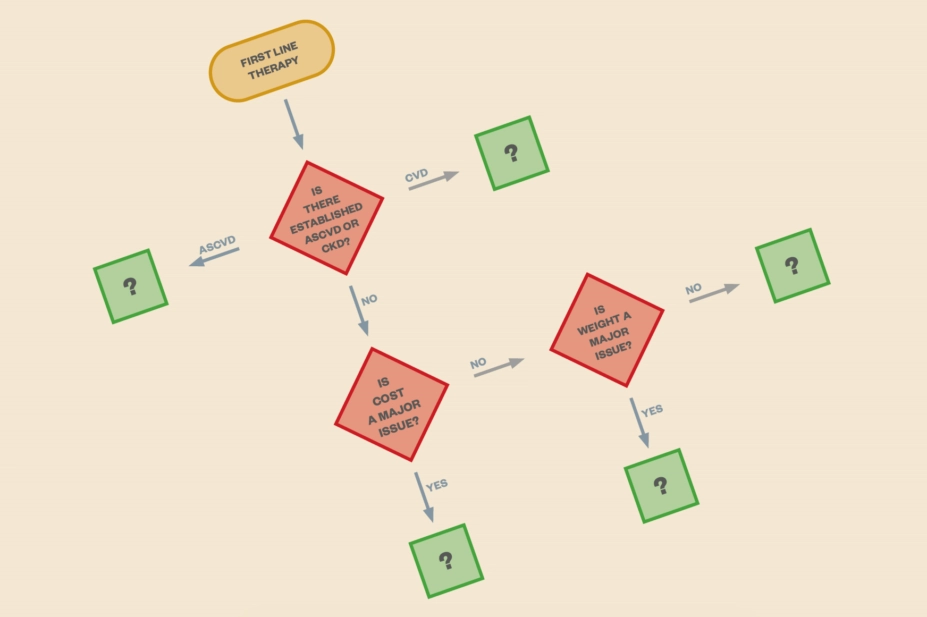

. The central theme of the report is the patient and their treatment goals, not just their HbA1c levels or the properties of the medicines they take. The goal of treatment could be reducing complications or maintaining quality of life in the context of comprehensive cardiovascular risk management and patient-centred care. The guideline advocates a shared decision-making approach to developing an achievable management plan that is frequently reviewed and modified. No arbitrary HbA1c target is set in the report — this will be dependent on individual patient preferences and characteristics. Treatment failure therefore equates to not achieving HbA1c targets that have been based on these individual patient characteristics. After failure to control HbA1c with metformin and lifestyle interventions, the next steps in the management algorithm are driven mainly by patient phenotypes. The choice of medicine added to metformin is based on patient preference and clinical characteristics. Important clinical characteristics include the presence of established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; other comorbidities, such as heart failure or chronic kidney disease; and risk of specific adverse medicine effects — particularly hypoglycaemia and weight gain. Safety, tolerability and cost are also considered.

As an example, consider a male taxi driver aged 60 years who: has had T2DM for 10 years; has a HbA1c of 73mmol/mol (8.8%); weighs 97kg; has a body mass index of 32; blood pressure of 150/90mmHg; an estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] of 44mL/min/1.73m2; an albumin-to-creatinine ratio of 19mg/mmol; and stage 3 chronic kidney disease. His current treatment options are metformin 1,000mg twice daily; sitagliptin 100mg once daily; and ramipril 2.5mg once daily.

Using the 2018 ADA–EASD glucose-lowering therapy guidance, the goals of care may be the avoidance of further complications and maintenance of a good quality of life. Kidney function, weight and the avoidance of hypoglycaemia are aspects of the patient’s medical history that will influence a decision on the next step of the glucose-lowering therapy. In this patient’s case, there is a compelling need to avoid hypoglycaemia and weight gain, so a GLP1-receptor agonist would appear to be the most reasonable option; of course, sitagliptin would have to be stopped in this instance. A SGLT2 inhibitor cannot be initiated as the patient’s eGFR is less than 60mL/min/1.73m2.

In this example, the ADA–EASD guideline questions whether an action may be appropriate for someone with certain characteristics, such as kidney impairment; the ADA–EASD guidance adds colour to NICE’s basic approach.

NICE must catch up with evidence

The NG28 guideline offers comprehensive patient-centred guidance on the management of T2DM; however, the generalist front-line clinician may struggle to choose the most appropriate pharmacotherapy to suit an individual person’s needs and circumstances, including preferences and comorbidities. The ADA–EASD consensus report and SIGN’s guidance for pharmacologically managing glycaemic control in people with T2DM offer more functional and prescriptive advice to healthcare professionals. If clinical guidelines for T2DM were an edifice, NG28 would be a wall, SIGN 154 would be a room and the ADA–EASD consensus report would be a house. T2DM guidelines must be more prescriptive on patient characteristics, rather than just on HbA1c control; therefore, the ADA-EASD report is the most user-friendly and prescriptive guidance for T2DM yet.

NICE’s guidance — despite specifying an individualised HbA1c target based on the person’s needs and circumstances, including preferences and comorbidities — is not prescriptive enough on the patient comorbidities, even though there is now ample evidence to support a benefit for patients with established cardiovascular disease when using some antidiabetic drugs. The generalist healthcare professional, whose focus is not diabetes, will need guidance on the various comorbidities that NG28 refers to. GPs in particular, who now manage around 90% of people with diabetes, are known to be less likely to follow clinical practice guidelines[8]

,[9]

and may be less likely to use the NG28 in the wake of the publication of the ADA–EASD consensus report.

Most pharmacists now have extended roles, as well as a wealth of pharmaceutical knowledge. Pharmacists who manage diabetes alongside GPs in primary care must be aware of various patient characteristics that must be considered before glycaemic drugs are prescribed. Prescribing leads at clinical commissioning groups (CCGs), who usually have significant control of local formularies, must also be aware that, although cost is a major issue in all CCGs, a patient-centred goal of avoiding complications is more important. Prescribing clinicians who are allowed to focus on patient-level characteristics are more likely to achieve the goals of treatment and, ultimately, reduce cost.

National spending on guideline development is futile if the guidance is ineffective and not adhered to — NICE needs to quickly catch up with the available evidence.

Samuel Seidu is a GP and primary care research fellow in diabetes.

Kamlesh Khunti is head of department and professor of primary care diabetes and vascular medicine.

Both at Leicester Diabetes Centre, Leicester General Hospital; Diabetes Research Centre, University of Leicester.

Correspondence to:

sis11@le.ac.uk

Acknowledgements

Samuel Seidu and Kamlesh Khunti both acknowledge support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (East Midlands) and the NIHR Leicester Biomedical Research Centre.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence was contacted for comment but failed to respond in time for publication.

References

[1] Field M & Lohr K. Guidelines for Clinical Practice: From development to use. Washington DC: National Academies Press. 1992. doi: 10.17226/1863

[2] Nam S, Chesla C, Scots NA et al. Barriers to diabetes management: patient and provider factors. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2011;93(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.02.002

[3] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Type 2 diabetes in adults: management. NICE guideline [NG28]. 2017. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28 (accessed January 2019)

[4] Trivedi H, Gray LJ, Seidu S et al. Self-knowledge of HbA1c in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus and its association with glycaemic control. Prim Care Diabetes 2017;11(5):414–420. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2017.03.011

[5] Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Pharmacological management of glycaemic control in people with type 2 diabetes. SIGN 154. 2017. Available at: https://www.sign.ac.uk/assets/sign154.pdf (accessed January 2019)

[6] Scottish Government & NHS Scotland. Quality prescribing for diabetes: a guide for improvement 2018–2021. Available at: https://www.therapeutics.scot.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Strategy-Diabetes-Quality-Prescribing-for-Diabetes-2018.pdf (accessed January 2019)

[7] Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia 2018;61(12):2461–2498. doi: 10.1007/s00125-018-4729-5

[8] Donker GA, Fleming DM, Schellevis FG et al. Differences in treatment regimes, consultation frequency and referral patterns of diabetes mellitus in general practices in five European countries. Fam Pract 2004;21(4):364–369. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh404

[9] Khunti K & Ganguli S. Who looks after people with diabetes: primary or secondary care? J R Soc Med 2000;93(4):183–186. doi: 10.1177/014107680009300407