From January 2016 , we will be gradually rolling out our new strategy for learning and CPD Integral to this strategy is the re-launch of Clinical Pharmacist as a peer-reviewed journal, as discussed in my previous blog post. We have been talking to our members and their employers to better understand the learning needs of pharmacy teams and based on the outcome of this research, we are adopting the concept of ‘learning objects’. We have created five article and our learning topics will be mapped broadly to the competency areas in the RPS’s Foundation programme (for early-year pharmacy professionals) and Faculty (for advanced practitioners in the discipline of Pharmacy), although not restricted to these resources.

Article types

The learning objects will be served in five article types. Learning and CPD articles may be accompanied by an online test, and the awarding of a certificate by The Pharmaceutical Journal for successful completion.

- Learning articles will be non-peer-reviewed and appear in The Pharmaceutical Journal. They focus on non-clinical skills pharmacy teams require. These areas include patient consultation, professionalism, organisation, teamwork, education and training, problem solving, research methods, service provision, management, medicines procurement, leadership, project management and similar soft skills that are essential to clinical practice. Learning articles may also provide quick updates or guidelines following recent news or regulations affecting pharmacy practice, drug approvals, clinical trials or management of a medical condition.

- Continuing Professional Development (CPD) articles will be peer-reviewed articles and appear in Clinical Pharmacist. CPD articles will be more clinically or scientifically focused, and enable pharmacists to develop their knowledge in specific therapeutic or scientific areas.

- Practice reports will appear in Clinical Pharmacist and be peer-reviewed reports that afford healthcare teams the opportunity to share innovations and initiatives that can improve pharmacy services. The reports may focus on any area of practice, including delivering clinical services, pharmacy administration, or new approaches to inform and engage with patients. As part of our criteria, it is essential that practice reports are accompanied by meticulous methodology to support reproducibility.

- Perspective articles present a viewpoint on an important area of investigation. They focus on a specific field or discipline and discuss current advances or future directions, and may include original data as well as personal insights and opinions. Perspective articles are peer-reviewed and will appear in Clinical Pharmacist.

- Review articles are peer-reviewed and cover topics that have seen significant development or progress in recent years with comprehensive depth, balanced perspective, intellectual insight, and broad general interest. Reviews do not merely summarise the literature, but should critique fundamental concepts, issues, and problems that define the field, and support advanced practitioners as well as aspiring early-year pharmacists.

The learning object

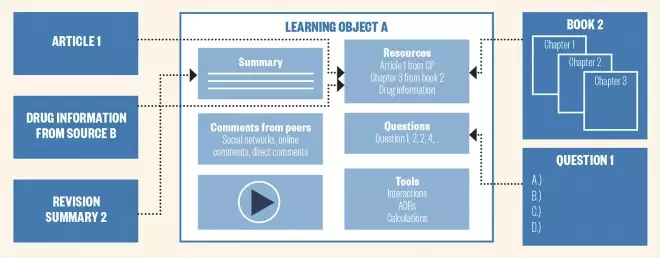

The concept of ‘learning objects is central to our strategy for CPD. A learning object is “a collection of content items, practice items, and assessment items that are combined based on a single learning objective”. The term is credited to Wayne Hodgins, a director of Worldwide Learning Strategies at Autodesk Inc. when he created a working group in 1994 bearing the name, but the concept was first described by Ralph W Gerard at the University of California in 1967. But to many the concept of learning objects is a new way of thinking about producing learning material or courses. Learning objects now go by many names, including content or knowledge objects, chunks, bits, nuggets, and units, amongst many other variations*.

A learning object is a digital self-contained and reusable entity, with a clear educational purpose, with at least three internal and editable components: content, learning activities and elements of context. The learning objects must have an external structure of information to facilitate their identification, storage and retrieval: the metadata.

Learning objects are a new way of thinking about learning content. They are:

- self-contained – each learning object can be taken independently;

- reusable – a single learning object may be used in multiple contexts for multiple purposes;

- collectable – learning objects can be aggregated into larger collections of content, including traditional course structures;

- tagged with metadata – every learning object has descriptive information allowing it to be easily identified.

By applying these concepts to various knowledge pieces we offer, we create a cohesive structure that can be used in myriads of ways. Out of several learning objects, we can create more complex modules around a learning subject that enable users to learn based on their own strengths and weaknesses and at their own pace.

The illustration below visualises the concept in the context of what we offer:

The concept of the learning object

Learning objects can be aggregated in many ways, if enriched with metadata.

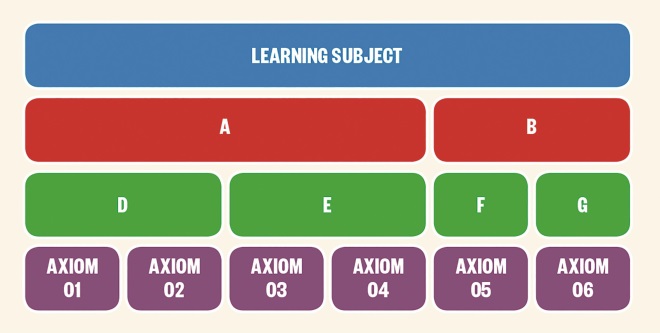

Another aspect of a learning object is self-containment. Each learning object should have one learning outcome and the learner will leave the object having learned about that single objective. This way, whenever devising an editorial plan for any learning resource, we will have a clear understanding of other existing learning resources in our own platform or and elsewhere, and will create a learning path, from the axiom (a statement or proposition which is regarded as being established, accepted, or self-evidently true) to the subject being taught.

Learning path, starting at the subject and moving down

Learning path for a learning topic area. The learner starts from the main topic and moves backwards, as far as the axiom.

For example, let’s say the learning object is ‘How thyroid dysfunction affects drug metabolism’. When designing the article, some assumptions are made that the learner already knows about the types of thyroid dysfunctions. If not, they can be directed to a resource where they can learn about various thyroid dysfunctions. In order to learn thyroid dysfunctions, the reader may need a reminder of the human endocrine system. They also may need information about the liver function, antidiabetic medicines, diabetes itself, cardiovascular agents, pharmacokinetics, adverse drug reactions and other pharmacologic phenomena.

By creating a reverse learning path, any learner at any level can start from that learning object and go as far back as they need, to the axiom itself.

In summary, the assumption is that the reader has already studied anatomy and physiology and pharmacology. This learning object needs to have a very specific learning objective and cannot become a resource for everything the reader needs to know, in order to understand the learning outcome of this object. The learning object (e.g. a CPD article), should be stripped of any background refresher, but provide access to resources that would enable the reader to become equipped with the knowledge to gain the learning objective of this CPD article. For example, a box on the CPD article listing the prerequisites for benefiting from this article, with links to resources on the platform (or another platform) to gain that knowledge, creates a self-containing learning object, with proper semantic relationship with lower level knowledge required (e.g. a chapter on drug metabolism in our textbook on pharmacokinetics).

In the classic model, if a learner does not have that background (or does not remember it) he or she cannot benefit from the specific learning objective of this learning object and learning will become a struggle. With the new model for learning, the reader can start learning from the top, and move back and forward between resources to collect all the knowledge necessary for gaining the learning outcome of the learning object.

The same principle should be applied from bottom to top. A learning object can inform the next steps in learning and provide a list of material for what the learner can read next, in order to advance her knowledge in that subject matter.

So, all in all, there are exciting times ahead. Join us on this journey.

*Variations include: content objects, chunks, educational objects, information objects, intelligent objects, knowledge bits, knowledge objects, learning components, media objects, reusable curriculum components, nuggets, reusable information objects, reusable learning objects, testable reusable units of cognition, training components, and units of learning.