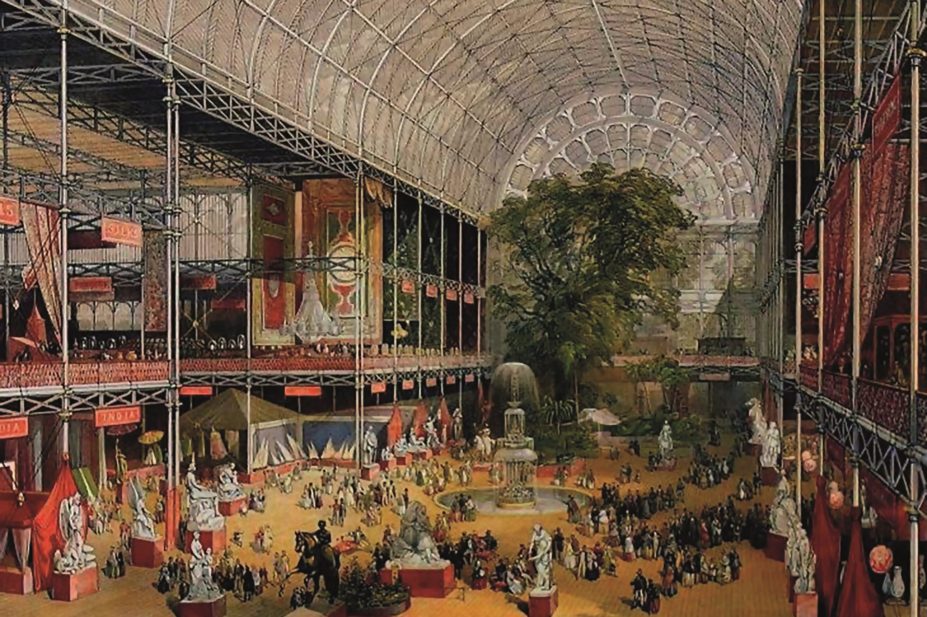

Wikimedia Commons

The Great Exhibition of 1851 was a once-in-a-generation opportunity for British pharmacy to showcase not only its products but also what it could offer to the public as well as the wider world. It took place just 10 years after the foundation of the Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain in 1841 and a year before passage of the first Pharmacy Act of 1852. Yet it was an event beset with disagreements and was judged by many to have been a missed opportunity.

Chief among its critics was Jacob Bell, the founder of the Society and the editor of The

Pharmaceutical Journal. Bell was heavily involved in the organisation and promotion of the exhibition. But he reflected afterwards that “the occasion afforded a favourable opportunity for showing to other nations what British commerce and manufacturing skill could produce in this department; but unfortunately it was not turned to the best account”.1

His concerns related to the limited presentation of pharmacy and the poor extent of the co-operation between pharmaceutical exhibitors. “The Great Exhibition is” he noted “something that many look back to with interest, and some with a mixture of satisfaction and regret, for it could not be said that British pharmacy was well represented there”.

The difficulty, not for the first time, was that of getting the pharmaceutical community to work together. Bell concluded that the poor representation was “principally caused by the difficulty experienced in getting those who were able to contribute articles for exhibition to act in concert, and to co-operate in carrying out a general plan for the display of such a collection of chemical and pharmaceutical products and drugs as might have been creditable to English pharmacy”.

According to the preface to the exhibition catalogue, written by Henry Cole, the purpose of the exhibition was “to present a true test and living picture of the point at which the whole of mankind had reached”. It was carried out by private means, was self-supporting and independent from taxpayer support. It opened on 1 May 1851, and 700,000 people lined the route of the procession of those involved in the opening ceremony2. By the time it closed, on 11 October 1851, some six million visitors had witnessed the displays of fifteen thousand exhibitors.

Strict rules existed as to what items would be accepted into the exhibition. The task of organising the classification of the exhibits fell to Lyon Playfair, himself a chemist. He divided them into four groups; raw materials; machinery; manufactures; and fine arts.

The organisers were persuaded that chemicals were part of commercial industry, and as a result pharmaceutical chemicals, especially alkaloids, were accepted, along with examples illustrating the state of the vegetable drug market. Together with innovative pharmaceutical machinery there was clearly no shortage of opportunity to promote the emerging pharmaceutical profession.

A suggestion was put forward that the Pharmaceutical Society itself should organise a collective exhibit, but the proposal was short-lived. Individual endeavour, it seems, trumped collective action. Well in advance of the opening, in September 1850, The

Pharmaceutical Journal reminded its readers that they should act quickly to apply for the space they needed.

One of the early tensions was between retailers and manufacturers. Some of the retailers threatened to withdraw if any manufacturer entered into competition with them. Specific regulations were then issued defining the principles on which the selection committees would act. They would attempt to “reward real merit, prevent quackery and avoid trade advertisement”.

The

Pharmaceutical Journal stressed that its readers should take part ‘in an honourable trial of skill with foreigners who are already in the field3. Foreign competition was formidable; alkaloids alone attracted entries from 18 firms, half of which were foreign.

Other initiatives aimed at collective action also failed. Discussion on the Drug Exchange led to the formation of a small committee tasked with organising specimens for a collective exhibit. But this made little progress, the result being “far less complete than originally contemplated”.

Pharmacy’s image was not helped by the fact that the organisers managed to let through a number of quack medicines, despite supposedly there being precautions in place to prevent this.

All the exhibits were judged by a panel, and those considered sufficiently worthy were awarded a Prize Medal. The chair of the Chemical Jury was a former French Minister of Agriculture and Commerce, and one of its eight members was Bell himself. The panel reviewed the entries of 270 exhibitors of which 132 were foreigners.

Bell was also one of the exhibitors, displaying both extract and tincture of Indian Hemp, an indication of the growing influence on British pharmacy of medicines of natural origin emanating from India.

1. Bell, J. and Redwood, T. (1880) Historical Sketch of the Progress of Pharmacy in Great Britain. London: Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 198-99.

2. Morson, A.F.P. (1997) The Great Exhibition of 1851, Pharmaceutical Historian, 27, 3, 27-30.

3. Editorial (1850-51) Pharmaceutical Journal, 10, 106.