MAG

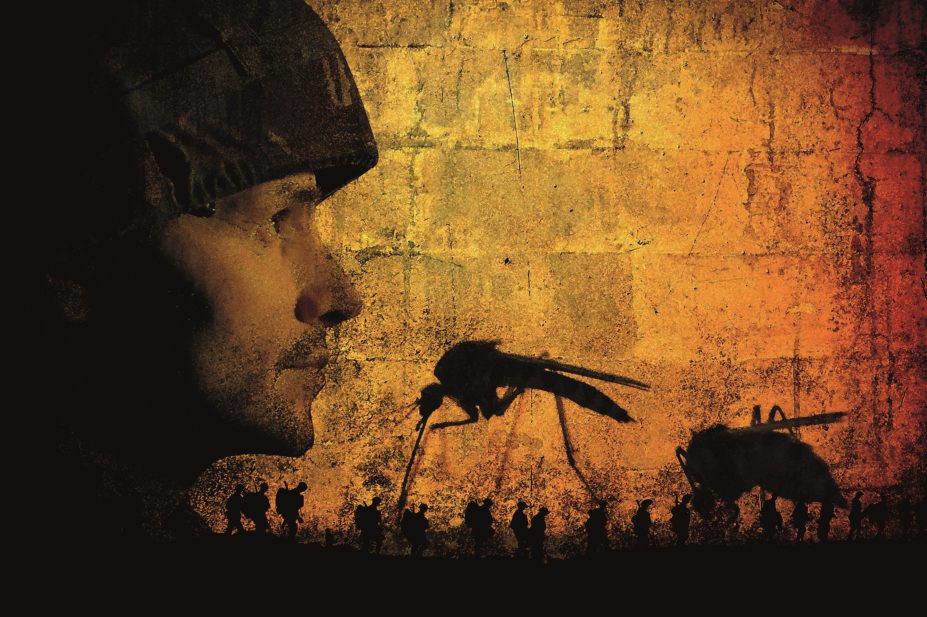

Mefloquine (Lariam, Larimef, Mefliam, Mephaquin) is in the news again. Since 1993, the mind- and mood-altering antimalaria drug has been routinely issued as first-line malaria prophylaxis for British soldiers[1]

. In the same year, mefloquine became associated with military atrocities when Canadian peacekeepers who were taking mefloquine beat, tortured and shot two local teenagers in Somalia[2]

. The pattern of mefloquine-associated military violence continued and, in 2002, four US soldiers based at Fort Bragg, North Carolina (three of whom had returned from Afghanistan, where troops were prescribed the drug) killed their wives[2]

. A more recent tragedy involved Staff Sergeant Robert Bales of the US special forces who, in March 2012, while apparently taking mefloquine, killed 16 Afghan civilians[2]

.

The French military have never prescribed mefloquine to its troops

[3]

. The US military, along with other national armies, have now stopped using the drug as first-line prophylaxis. If used at all, it is relegated to third line[4]

. In the UK, civilian GPs “steer clear” of mefloquine, states Clare Gerada, former chair of the Royal College of General Practitioners[5]

. However, the UK Ministry of Defence continues to issue it routinely (‘prescribing’ isn’t the correct word, since the drug is typically handed out on the parade ground by the medical sergeant, along with other tropical kit) to troops deploying on exercise or operations to sub-Saharan Africa[5]

.

Parliamentary concern

On 8 September 2015, the UK Parliament’s defence select committee wrote to the defence secretary, Michael Fallon, to ask if he planned to reassess mefloquine’s safety, in light of renewed military concerns[6]

. This followed an announcement by Johnny Mercer, Conservative MP for Plymouth Moor View, that he had received “dozens” of letters from military personnel who believed they had been harmed by mefloquine[7]

. Mercer further stated that, according to official records, of 1,892 UK military personnel who took mefloquine in 2014, 263 (14%) had sought treatment for its side effects. Since 2008, 994 service personnel had been admitted to psychiatric hospitals or had been treated at mental health clinics after taking the drug[7]

, he added. The true figures, however, may be even higher[8]

.

The news that mefloquine was still being administered wholesale to soldiers astonished parliamentarians and many doctors. Its potential to cause neuropsychiatric harm was highlighted as long ago as November 1995 in BBC television’s consumer programme Watchdog[9]

. After this early media exposure, mefloquine sales slumped[10]

. A Cochrane review in 1997 confirmed that it causes serious side effects[11]

, and a more recent Cochrane review in 2009 showed that it is the least safe malaria prevention drug in terms of its potential to cause neuropsychiatric injury and sudden death[12]

.

Lamentable history

Mefloquine was developed by the US army for malaria treatment in the 1970s through controversial experiments involving the deliberate infection of participants with Plasmodium falciparum

[13],[14]

. The participants were, in fact, prisoners in state penitentiaries, although some of the study reports concealed this fact[15]

. On the strength of these early studies in prisoners, mefloquine was licensed and prescribed from 1984 onwards to tourists and travellers[16]

. Not only were the end-users of the drug different from the original study populations, but the principal indication for mefloquine’s use had also changed: it was prescribed, and continued to be prescribed, mainly for malaria prevention[17]

.

The evidence base for mefloquine’s use as prophylaxis was inadequate in 1984 and it is inadequate today. In the rush to license mefloquine, vital safety and pharmacokinetic studies were skipped[16]

. Even now, these have not been performed. Early in mefloquine’s history, experts came forward to declare, on the basis of almost no evidence, that the drug was “non-toxic” and “well tolerated”. This was disproved, however, by hundreds of peer-reviewed scientific case reports (there were 516 reports by March 2002) describing unwanted mefloquine effects such as headache, nervousness, fatigue, disorders of sleep, mood, memory and concentration, and occasionally frank psychosis[18]

. One such report was called ‘Curses, madness and mefloquine’[19]

.

Specious arguments

There is no organisation more entrenched than a government department whose senior members are anonymous and unaccountable to the general public. Safer alternatives to mefloquine (doxycycline and atovaquone/proguanil [Malarone], for example) have been available for decades. To date, the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD) has refused to budge from its 20-year position that mefloquine is “the drug of choice” for soldiers deploying to sub-Saharan Africa. Its arguments for maintaining the pharmacological status quo have been confused and, at times, contradictory, and have been aired by the MoD press office in government-controlled websites, rather than in scientific journals[20]

. To date, three broad themes, all of them flawed, have emerged.

Argument one: “We follow Public Health England”. Why? Public Health England exists to advise English civilian travellers on travel health matters. It is not constituted (and nor should it be) to advise the military. Military travellers differ from civilian travellers in at least ten fundamental respects

[4]

. The UK military needs to look at its own population to decide its own malaria policy, based on its unique exposure threat and its unique workforce demography[21]

. All other large national armies do this. The Defence Medical Services did this until around 1997, after which time they relied too heavily on civilian advisers.

Argument two: “Malaria is a life-threatening disease and strong drugs are needed to prevent it; inevitably, these have side effects”. Yes, but mefloquine causes neuropsychiatric illness, and doxycycline and Malarone, on the whole, do not[12]

. The British National Formulary lists 27 neuropsychiatric side effects linked with mefloquine, seven linked with Malarone, and two linked with doxycycline[22]

. The neurological side effects of mefloquine can be permanent, as the US Food and Drug Administration confirmed in 2013[23]

. Doxycycline and Malarone are as effective as mefloquine in preventing malaria[24]

. Malaria, in any event, is easily diagnosed and treated, and its risk to soldiers has been overstated by successive surgeon generals. No soldier has died of malaria recently. Even before mefloquine’s adoption, no British soldier had died from malaria for at least 20 years[1],[25]

.

Argument three: “There is no evidence to suggest that mefloquine interferes with weapon handling”. Wrong. Participants taking mefloquine in a small cross-over randomised controlled trial consistently made more errors on a flight simulator than when taking placebo[26]

. For precisely this reason, aircrew are not permitted to take mefloquine[27]

. A loaded weapon is a complex piece of machinery, analogous in many ways to a helicopter or a fixed wing aircraft. It is just as dangerous.

It’s time to stop

The MoD’s continued use of mefloquine as routine, first-line malaria prophylaxis for soldiers, based on disastrous advice over a 20-year period from successive surgeon generals, is scientifically and ethically indefensible. It must stop, immediately.

What should replace mefloquine as first-line prophylaxis in locations where chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria is known to exist? The answer is doxycycline – but in its monohydrate, not hyclate, form. Doxycycline protects against other tropical infections besides malaria. Doxycycline monohydrate, marketed in the UK as ‘Efracea’, has significantly fewer side effects than doxycycline hyclate

[24]

. Since doxycycline monohydrate is not currently licensed in the UK for malaria prophylaxis (although it is licensed in Europe), the onus is on the MoD to press for this doxycycline formulation to be licensed for this indication, and to make it available to our troops.

References

[1] Miller SA, Bergman BP & Croft AM. Epidemiology of malaria in the British Army from 1982–1996. J R Army Med Corps 1999;145:20–22. PMID:10216843

[2] Owen J. Lariam: history of violence. The Independent. 27 September 2013, 4–5.

[3] Croft AM, Darbyshire AH, Jackson CJ et al. Malaria prevention measures in coalition troops in Afghanistan. JAMA 2007;297:2197–2200. doi:10.1001/jama.297.20.2197-c

[4] Magill AJ, Forgione MA, Maguire JD et al. Special considerations for US military deployments. In: Brunette GW, ed. CDC health information for international travel. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

[5] Owen J. MoD ‘ignored years of warnings about the dangers of suicide drug’. The Independent. 27 September 2013, 4–5.

[6] O’Dowd A. MPs may hold inquiry into safety of using antimalarial mefloquine in military. BMJ 2015;351:h4868. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4868

[7] Mercer J. How veterans’ pleas convinced me that ‘suicide drug’ should stop being prescribed to Armed Forces. The Independent. 17 August 2015, 1–2.

[8] Editorial. Alarm over Lariam. The Times. 25 September 2015, 35.

[9] Clift S & Grabowski P. Malaria prophylaxis and the media. Lancet 1996;348:344.

[10] Tansley R, Lotharius J, Priestley A et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to investigate the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of single enantiomer (+)-mefloquine compared with racemic mefloquine in healthy persons. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2010;83:1195–1201. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0228

[11] Croft AM & Garner P. Mefloquine to prevent malaria: a systematic review of trials. BMJ 1997;315:1412–1416. doi:10.1136/bmj.315.7120.1412

[12] Jacquerioz FA & Croft AM. Drugs for preventing malaria in travellers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(4):CD006491. doi:10.1002/14651858.

[13] Trenholme CM, Williams RL, Desjardins RE et al. Mefloquine (WR 142,490) in the treatment of human malaria. Science 1975;190:792–794. PMID:1105787

[14] Clyde DF, McCarthy VC, Miller RM et al. Suppressive activity of mefloquine in sporozoite-induced human malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1976;9:384–386. PMID:769678

[15] Rieckmann KH, Trenholme GM, Williams RL et al. Prophylactic activity of mefloquine hydrochloride (WR 142490) in drug-resistant malaria. Bull World Health Organ 1974;51:375–377. PMID:4619059

[16] Croft AM. Developing safe antimalaria drugs: key lessons from mefloquine and halofantrine. International Journal of Risk & Safety in Medicine 2007;19:153–161.

[17] Croft AM. A lesson learnt: the rise and fall of Lariam and Halfan. J R Soc Med 2007;100:170–174. doi:10.1258/jrsm.100.4.170

[18] Croft AM & Herxheimer A. Adverse effects of the antimalaria drug, mefloquine: due to primary liver damage with secondary thyroid involvement? BMC Public Health 2002;25:6. PMID: 11914150

[19] Kukoyi O & Carney CP. Curses, madness, and mefloquine. Psychosomatics 2003;44:339–341. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.44.4.339

[20] BBC News. Ministry of Defence defends use of malaria drug. 25 September 2015.

[21] Croft AM, Baker D & von Bertele MJ. Une politique de lutte antivectorielle adaptée aux déploiements militaires selon des résultats d’études: l’expérience de l’armée britannique. Med Trop (Marseille) 2001;61:91–98.

[22] Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. Antimalarials. In: British National Formulary No 69. London: Pharmaceutical Press, 2015.

[23] Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves label changes for antimalarial drug mefloquine hydrochloride due to risk of serious psychiatric and nerve side effects. FDA Safety Announcement, 29 July 2013.

[24] Croft AM, Jacquerioz FA & Jones KL. Drugs to prevent malaria in travelers: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Human Parasitic Diseases 2010;2:1–19.

[25] Croft AM & Geary KG. The malaria threat. Med Trop (Marseille) 2001;61:63–66. PMID:11584659

[26] Schlagenhauf P, Lobel H, Steffen R et al. Tolerance of mefloquine by SwissAir trainee pilots. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1997;56:235–240. PMID: 9080886

[27] Nosten F & van Vugt M: Neuropsychiatric adverse effects of mefloquine – what do we know and what should we do? CNS Drugs 1999;11:1–8.