Museum of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society

By Szu Shen Wong, Thibaut Deviese, Jane Draycott, John Betts and Matthew Johnston

Marriage a-la-Mode No. 3 (The Inspection) belongs to a six part series of paintings by English painter, printmaker and society critic, William Hogarth. The print in the possession of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s (RPS) Museum depicts Viscount Squanderfield and his child mistress visiting a quack. Viscount Squanderfield, who is seated and holding up a pill box to the quack doctor, is depicted with a large black spot on his neck. This spot is often interpreted as a syphilis sore and the pills are likely to be mercury pills. His child mistress holds another pill box whilst dabbing the edge of her mouth, which may indicate she could be suffering from excessive salivation as a result of mercury poisoning or she could be dabbing an oozing sore.

Source: Museum of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society

Mercury pills were popular for treating syphilis from the 17th to 19th century.

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted disease caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum and has four stages. Three of the four has manifestations on the skin of the sufferer. In the primary stage, painless ulcers or chancres appear on the genitals and if allowed to progress into the secondary stage, blotchy red rashes appear, usually on the palms of hands and soles of the feet. Occasionally, hair loss also develops at this stage. This is then followed by a latent stage during which sufferers have neither sign nor symptom of the disease. This stage can last for years. During the tertiary stage of syphilis, the skin, bones, internal organs, nervous system and cardiovascular system begin to be irreversibly damaged. Patients are often ostracised from society and suffer from severe disfigurement.

Hogarth’s Marriage a-la-Mode can be interpreted as 18th Century syphilis awareness campaign posters. Viewers are made aware of the early symptoms of the disease and the side effects of its ineffective treatments. Hogarth also hints at the mode of transmission and that it is contagious. The necrosis of the bone on the skull of a previous patient with tertiary syphilis can also be seen on the table situated next to the quack doctor in the print.

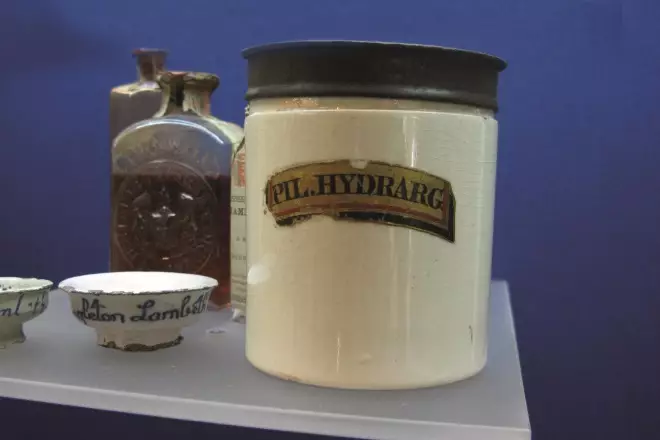

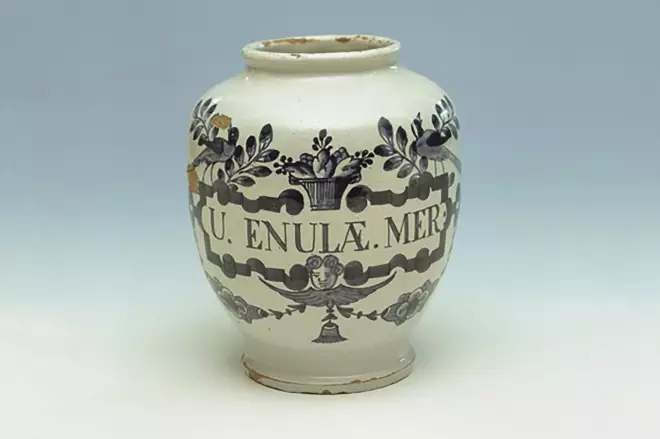

Mercury was the remedy of choice for syphilis in Protestant Europe. Paracelsus (1493-1541) formulated mercury as an ointment because he recognised the toxicity and risk of poisoning when administrating mercury as an elixir. Mercury was already being used in Western Europe to treat skin diseases. The Hogarth print depicts a shelf of apothecary ceramic jars — one or two may contain mercury ointment. The RPS museum has a tin-glazed earthenware jar with a label which reads ’Elecampane and mercury ointment’ dating from around 1700–30 and would have been available from apothecaries during Hogarth’s time. Mercury ointments continued to be used well into the 19th and early 20th century. One such ointment is the No-Name Ointment made by John Whitehouse from Deritend, Birmingham (also in the RPS collection).

Source: Museum of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society

A mercury ointment jar at the museum of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society.

The mercury, or ‘blue mass’, pills shown in the print were popular from the 17th to 19th century and used mercury in its elemental form or compound form, usually mercurous chloride (also known as calomel). The first effective treatment for syphilis, Salvarsan, was only found in 1910 — five years after the causative bacterium was identified by Fritz Schaudinn (a zoologist) and Erich Hoffmann (a dermatologist).

Salvarsan was developed by Nobel Prize winner Paul Ehrlich and his Japanese assistant Sahachiro Hata. Salvarsan and its more stable and soluble version, Neosalvarsan, were arsenic derivatives and treatment was affected by severe side effects. It would be the 1940s when penicillin would finally be proven to be effective against syphilis and it remains the antibiotic of choice to this day.

Source: Museum of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society

Salvarsan was the first effective treatment for syphilis.

Syphilis can now be cured with treatment but in Hogarth’s day, patients would eventually succumb to the disease if they had not already been fatally poisoned by the mercuric treatment. Hogarth cleverly foreshadows this in the print using a skeleton suggestively leaning against an embalmed body in the cabinet behind Viscount Squanderfield.

This work was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AH/N007174/1) and was carried out as part of a collaborative project between the Royal Pharmaceutical Society Museum and the University of Oxford, University of Nottingham and the University of Wales Trinity St David.