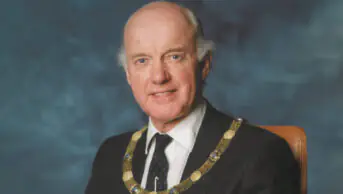

Courtesy of Theo Rayner

Thomas Geoffrey Booth, former president of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS), who has died aged 88, was an important figure in the development of the department of pharmacy at the University of Bradford, where he spent his whole career and set up the UK’s first department in pharmacy practice.

A committed and enthusiastic teacher, Geof, as he liked to be known, was active in pharmacy politics locally and nationally for much of his life and is remembered fondly by generations of students.

“He conducted serious council business with true Yorkshire grit and a sense of humour both at headquarters in Lambeth, London, and in Yorkshire,” recalls a former student Gill Hawksworth, visiting fellow at the University of Huddersfield and also a former RPS president. Hawksworth, who was Booth’s student in the 1970s, said: “He was my role model and I would not have been able to develop my career in pharmacy education and politics without his mentorship and support.”

Booth was born in Bradford where his father, Thomas, worked for the Post Office. He attended St Bede’s catholic grammar school in the city and spent three years in the Fleet Air Arm before going to Bradford Technical College, which, in 1966, became the University of Bradford.

In 1966 he established the pharmacy department’s pharmacy practice research unit, the first in the UK, and, in 1969, obtained his PhD in pharmacy practice. In 1988, he became the first professor of pharmacy practice in the UK and was awarded an OBE.

Marcus Rattray, head of Bradford School of Pharmacy, said: “Geof was a trailblazer establishing the discipline of pharmacy practice to ensure pharmacists have communication and clinical skills for patient benefit and safe and effective use of medicines. He identified a gap in education he could see was holding back patient care.”

Peter Taylor, honorary professor of pharmacy practice at the University of Bradford, was an undergraduate in Booth’s department from 1967 to 1970 and believes Booth was visionary in seeing the need to introduce new elements, such as business skills, law and people management, into the curriculum. Booth was a strong advocate for practice-based research. “Before that, the emphasis had been on the science but then the focus became the patient — how to reduce side effects and the tailoring of drugs to individual patients,” said Taylor, former director of pharmacy at Airedale NHS Foundation Trust. “On a personal level he inspired us to undertake research and to become the best pharmacists we could,” he added.

Alison Blenkinsopp, professor of the practice of pharmacy at the University of Bradford, says Booth was “an incredibly kind, thoughtful and wise man, with a mischievous sense of humour who put pharmacy practice research on the map”.

Theo Raynor, who became inaugural professor of pharmacy at the University of Leeds in 2000, remembers Booth for his extreme kindness when he was supervising Raynor’s PhD in the 1980s. “I was writing up the research part time alongside my day job and, to help me, my wife would go off at the weekends with our two small children. I mentioned this in a supervisory meeting and shortly afterwards a handwritten letter to my wife arrived, thanking her for the sacrifices she was making. He was a great man.”

Booth was elected to the Council of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society in 1978 and served as president from 1985 to 1987. In 1991, he was awarded the Society’s Charter gold medal for outstanding service to the profession. In response, Booth said he enjoyed every minute of his academic work and was always given a royal welcome on his many visits to branches and regions. Getting pharmacy practice to become an established academic discipline had been a 30-year obsession for him, he added. Booth also spoke of his satisfaction at seeing former students take up leading roles in the profession.

He spent several years on the Committee on Safety of Medicines and was a member of Bradford Family Practitioner Committee (later Bradford Family Health Services Authority). He also acted as external examiner for the postgraduate diploma in community pharmacy at King’s College, London.

Booth, who lived in Harrogate, retired in 1992. At the time of his death he had been ill for some time. A diabetic patient, he had lost both legs and lived with a pacemaker.

He is survived by his wife Mary, to whom he was married for 62 years.

You may also be interested in

Philip Leon Marshall Davies (1938–2026)

Bill Scott OBE (1949–2025)