Abstract

Aim

To describe the number and types of patient safety incidents involving Controlled Drugs reported to the National Reporting and Learning System (NRLS) and the role of Accountable Officers for CDs (AOs) in incident reporting and learning.

Design and setting

All medication safety incidents concerning CDs reported from the NHS in England and Wales occurring in the seven years from 1 January 2005 to 31 December 2011 were extracted from the NRLS and subject to quantitative inspection. In addition incidents with reported outcomes of death and severe harm were also analysed qualitatively.

Results

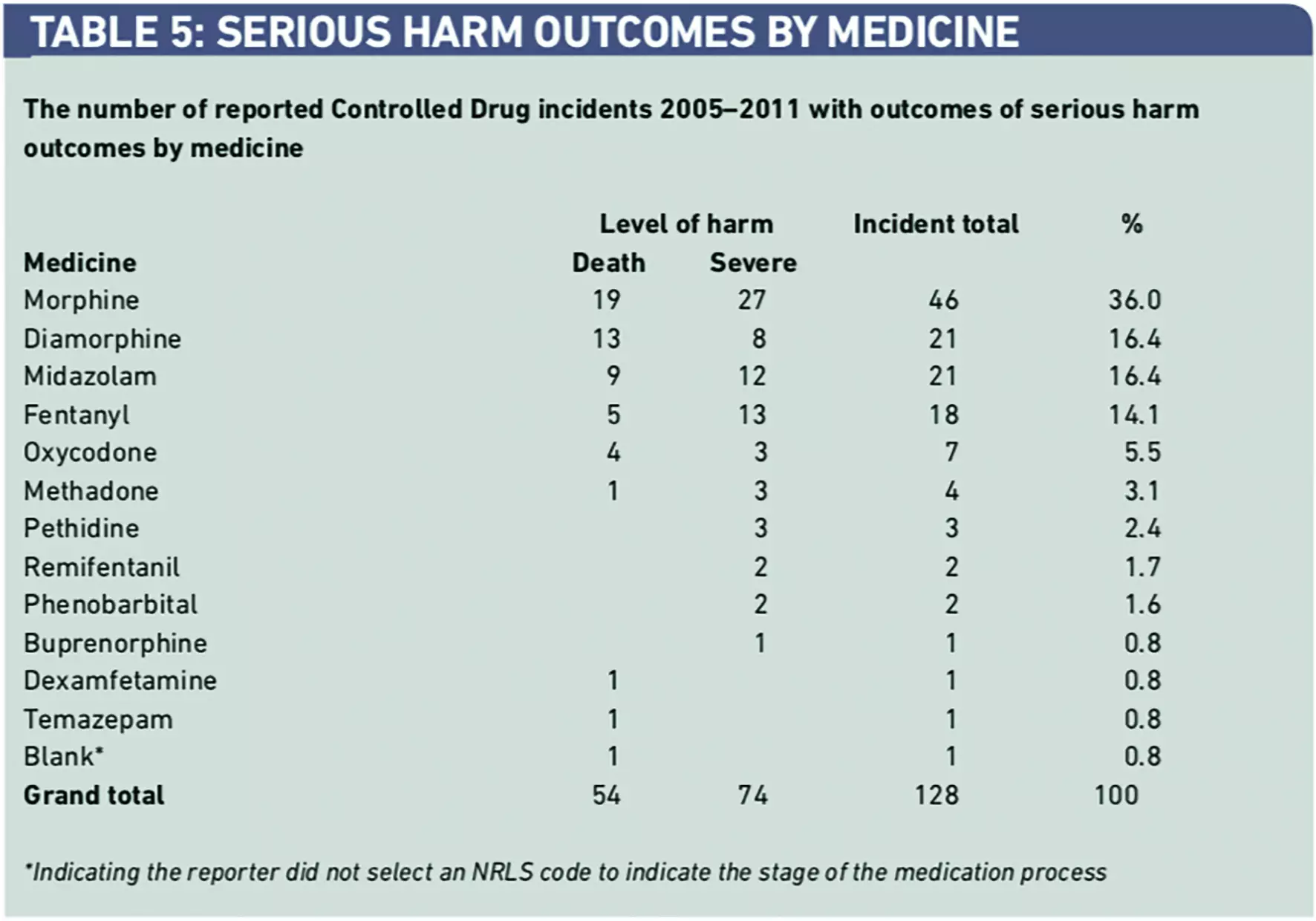

There were 72,028 in incidents reported to the NRLS over seven years. Of 10,678 incidents of reported harm, there were 54 deaths, 74 severe harms and 10,550 incidents of other harms. The risk of death with CD incidents was found to be significantly greater than with medication incidents generally (odds ratio 1.484, 95% CI 1.015–2.169). Incidents involving overdose of CDs accounted for 89 (69.5%) of the 128 incidents reporting of serious harm (death and severe harm). Five CDs (morphine, diamorphine, fentanyl, midazolam and oxycodone) were responsible for 113 incidents (88.4%) leading to serious harm. A detailed review of the 128 incident reports associated with serious harm found that only once incident had been referred to the AO.

Conclusion

Unsafe use of CDs is the number one cause of serious harm from medication incidents reported to the NRLS; in our view, better implementation of NPSA guidance could have prevented most of these incidents from harming patients. The role of the AO should prioritise reporting and learning of incidents that have caused serious harm.

In a previous review of all medication incidents reported to the National Reporting and Learning Service (NRLS) opioid medicines were identified as causing the greatest number of incidents with fatal and severe outcomes.1 The National Patient Safety agency has issued guidance intended to help minimise dosing errors with opioid medicines.2–5

Controlled Drugs are an essential part of modern clinical care and are used to treat a wide variety of clinical conditions. They are however, subject to special legislative controls because there is potential for them to be abused, diverted or cause possible harm.6

In response to the Shipman Inquiry Fourth Report,7 the Government introduced a range of measures to strengthen the systems for managing CDs to minimise the risks to patient safety of inappropriate use. The arrangements were underpinned by the Health act 2006 and The Controlled Drugs (Supervision of Management and Use) Regulations 2006 made under the provision of the act. The governance arrangements embedded within the regulations are required to be implemented in a way that supports professionals, and encourages good practice in the use of these important medicines, when clinically required by patients.6

Accountable officers (AOs) were given specified responsibility to minimise the risk to patients from CDs. The regulations indicate that in discharging their responsibilities, an AO must have regard to best practice in relation to the management and use of CDs.

We have undertaken a quantitative review of all medication incidents involving CDs sent to the NRLS over a seven-year period. In addition, for those incidents with reported outcomes of death and severe harm we have undertaken a qualitative review. Our aims were to better understand the types of incidents and the role of AOs in reporting and learning.

Method

All medication safety incidents concerning CDs reported as occurring in the seven years from 1 January 2005 to 31 December 2011 were extracted from the NRLS database and subjected to quantitative inspection. In addition incidents with reported outcomes of death and severe harm were also analysed qualitatively. Where the clinical outcome of the incident description matched NRLS definitions,8 the clinical outcome code was confirmed. Where the incident description did not match the outcome code reported, a more appropriate clinical outcome code based on the NRLS reference definition was substituted (DG), to reflect more accurately the details of the reported incident. The quantitative inspection was based upon the amended clinical outcome scores.

The working definition of severe harm used for the review was “a patient safety incident that appears to have resulted in permanent harm and/or a near death experience”. Incidents were considered not applicable (NA) if they were adverse drug reactions where the harm was not avoidable, the incident was miscoded, there was insufficient information to make any judgement of clinical outcome or no assessment of level of harm was reported. In this text, reference to serious harm is reported death or severe harm.

Those incidents identified as causing serious harm were inspected for underlying themes. The full dataset was filtered for occurrence of the words “accountable officer” or “AO” and the resulting subset inspected and grouped under the themes identified for incidents associated with death or severe harm. The role of the AO was reviewed in all incidents where death or severe harm occurred.

The full dataset was inspected for incidents according to the stage of the medication process and reporting from community pharmacy and general (medical) practice.

Results

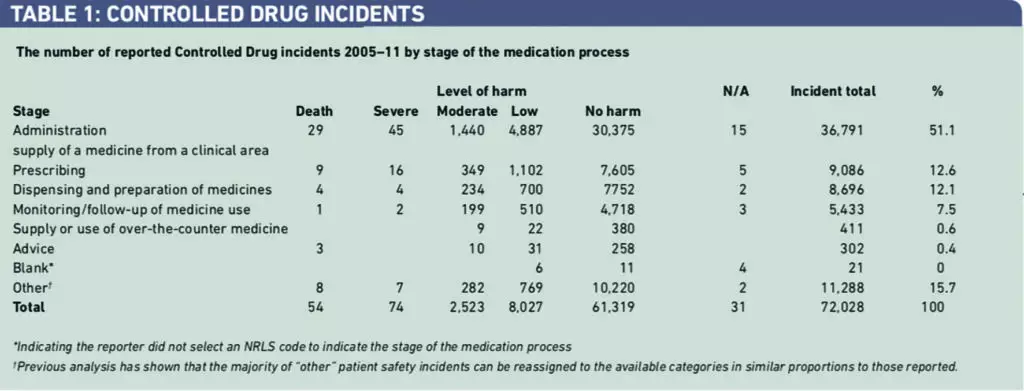

There were 72,028 in incidents reported to the NRLS over seven years (Table 1). Of 10,678 incidents of reported harm, there were 54 deaths, 74 severe harms and 10,550 incidents of other harms. Over 50 per cent of the CD incidents involved medicines administration. The category “other” was the second largest category. The level of reported serious harms involving CDs was compared with results of our previous review of all medication incidents (271 deaths, 551 severe harms) over the same time period.1 The risk of death as a serious harm with CD incidents was found to be significantly greater than with medication incidents generally [odds ratio 1.484, 95 per cent CI 1.015–2.169].

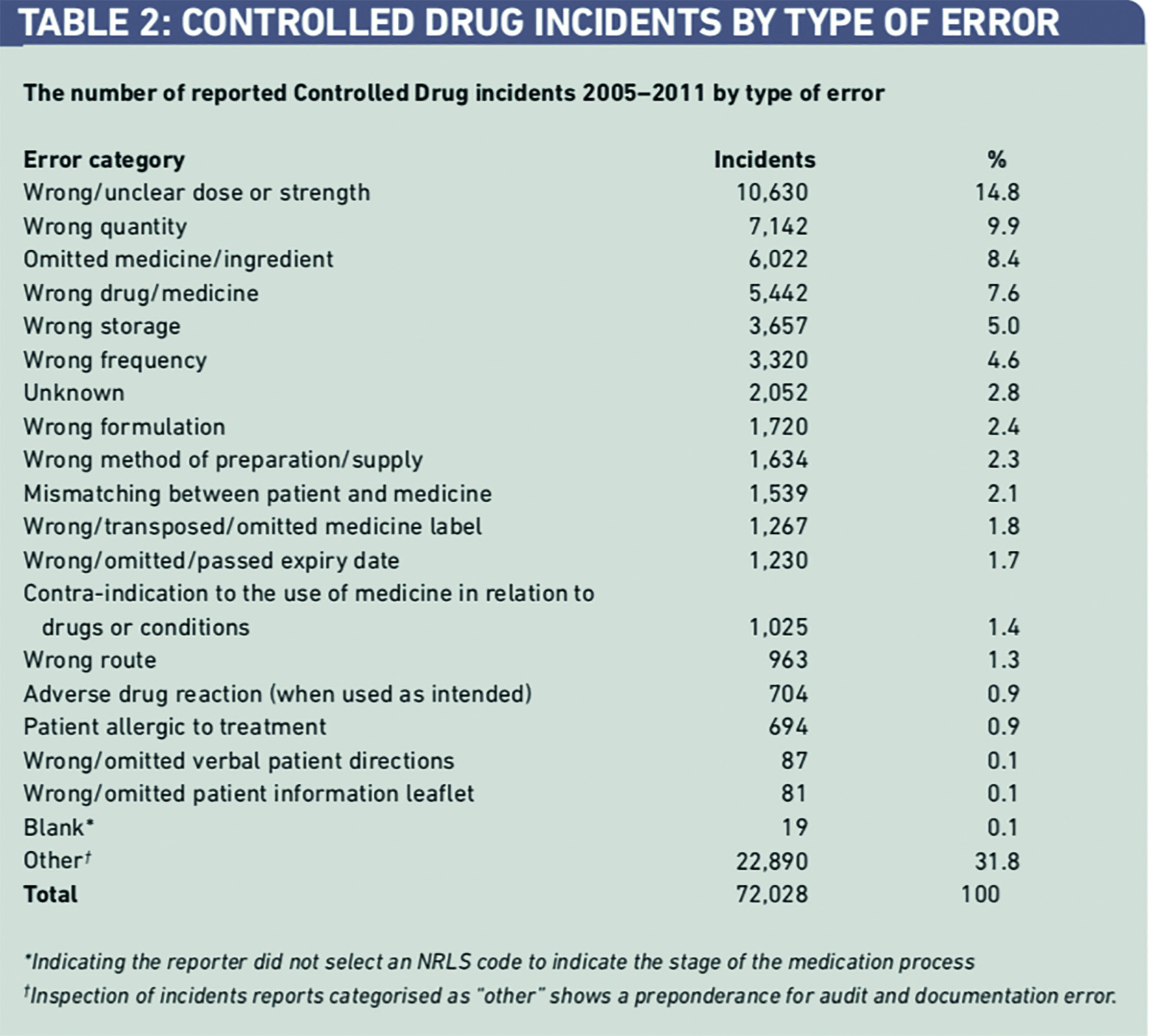

The largest type of error category was “other”. Some 22,890 incidents (31.8 per cent) were not allocated to common patient safety categories by the reporters (Table 2). Inspection of these reports indicated that errors in CD documentation and storage were the most frequently reported types of incident in this category. It was not always clear how these types of error had caused harm or had the potential to cause harm to patients. “Wrong or unclear dose” received the next largest number of incident reports 7,142 (14.8 per cent).

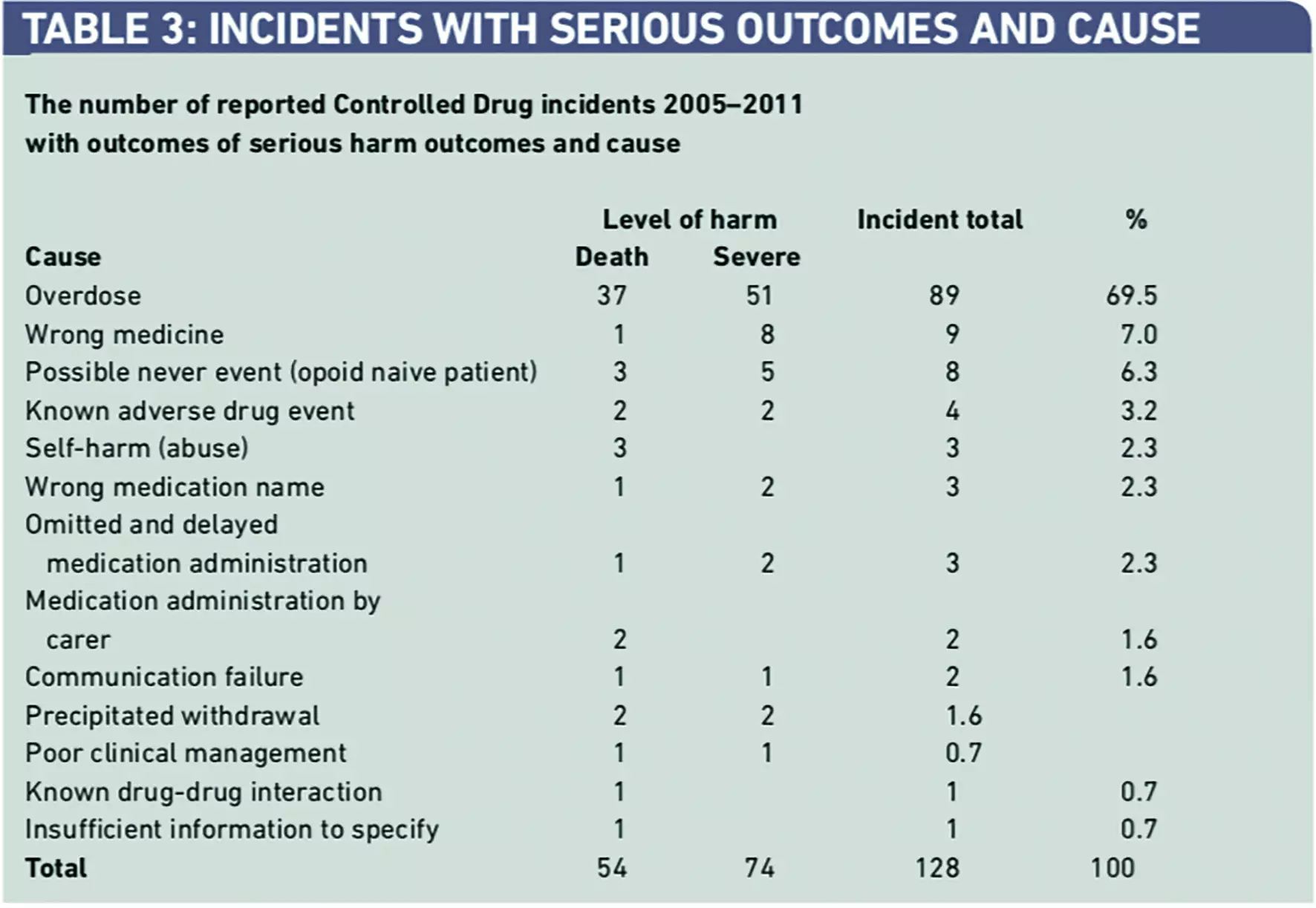

Incidents involving overdose of CDs accounted for 89 (69.5 per cent) of the 128 incidents of serious harm (death and severe harm) (Table 3).

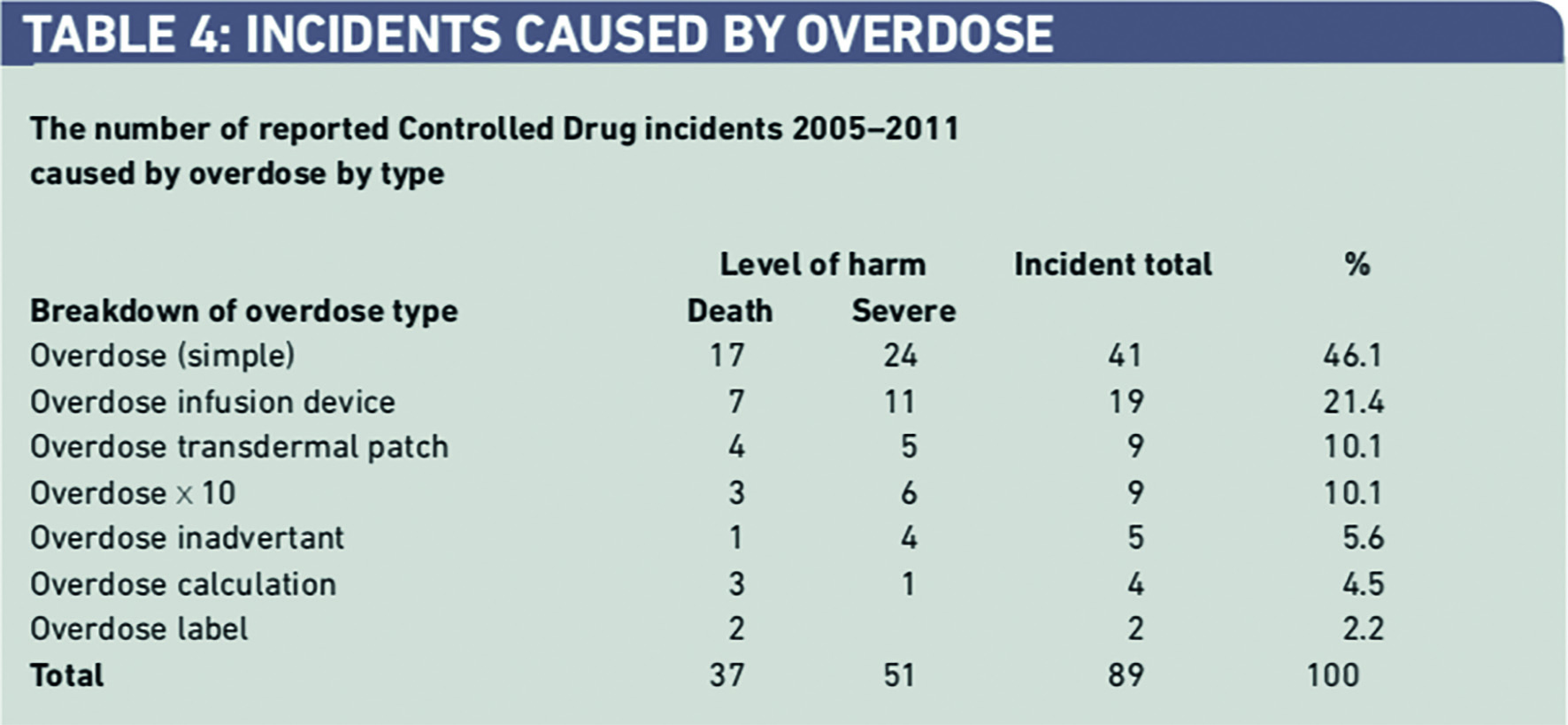

More detailed analysis of these reports indicates that simple overdose errors were responsible for 41 (46.1 per cent) of these incidents followed by over-infusion involving an infusion device, overdose from a transdermal patch, and “10x” errors (Table 4).

Five CDs (morphine, diamorphine, fentanyl, midazolam and oxycodone) were responsible for 113 incidents (88.4 per cent) leading to serious harm (Table 5).

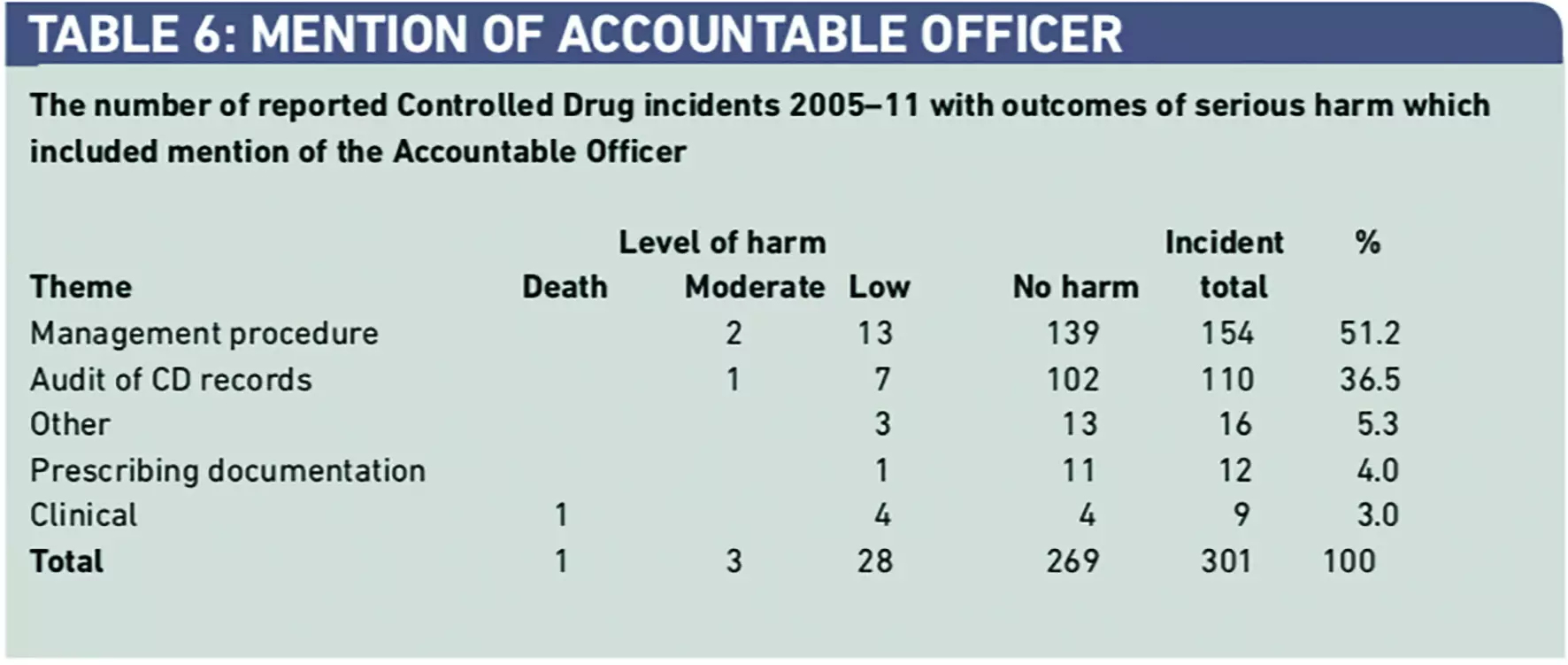

A detailed review of the 128 incidents associated with serious harm revealed that in 112 reports (87.6 per cent) better compliance with previously issued NPSA guidance2–5 would have helped prevent these incidents. The review of these same incidents found that 125 (97.7 per cent) of them should have been referred to the AO. A surprising finding was that referral to the AO was only mentioned in one report (0.8 per cent).

Of the full dataset, 301 reports (0.4 per cent) included reference to the “Accountable Officer” or “AO” (Table 6). Only 32 incidents (10.6 per cent) that had been referred to AOs, had caused harm. This indicated that evidence that AOs had been informed that a patient had been harmed from use of a CD in 32 (0.3 per cent) out of a total of 10,678 incidents reported to the NRLS. Most incidents that were referred to AOs concerned breaches of safe custody and documentation procedures, with only 3.0 per cent of incidents involving the safe clinical use of CDs.

Qualitative analysis of the incidents that did include mention of the “AO” is shown in Panel 1. Results from qualitative analysis supports the findings in both Table 1 concerning incidents categorised as “Other” and in Table 6, which indicate the focus of the current role of an AO is on safe custody and documentation, rather than on reports and learning arising from the clinical use of a CD where a patient has died or been harmed.

Panel 1: Qualitative analysis

Qualitative analysis of Controlled Drug incidents 2005–11 with outcomes of serious harm which included mention of the accountable Officer

Management procedure

Cases where written procedures were not followed including storage, transfer between different locations, identification of faulty or leaking stock, identification of out-of-date stock, incorrect dispensing, supply to the wrong patient and, dominantly, supply of the wrong strength.

Audit of Controlled Drugs records

Cases where the audit process revealed discrepancies in stock levels, which often resulted in retrospective identification of incorrect administration of medication. In some cases audit of drug charts and reconciliation with the Controlled Drugs register identified medication safety incidents.

Prescribing documentation

Cases where failure to provide an accurately completed prescription form or CD requisition resulted in delays in treatment.

Clinical

Rare cases where the Accountable Officer was involved in a patient safety incident where clinical decisions involving CDs had put patients at risk of harm.

Other

Cases of deliberate abuse of CDs, excessive quantities of CDs prescribed and dispensed. Lack of available storage facilities, deliberate theft of CDs and trafficking.

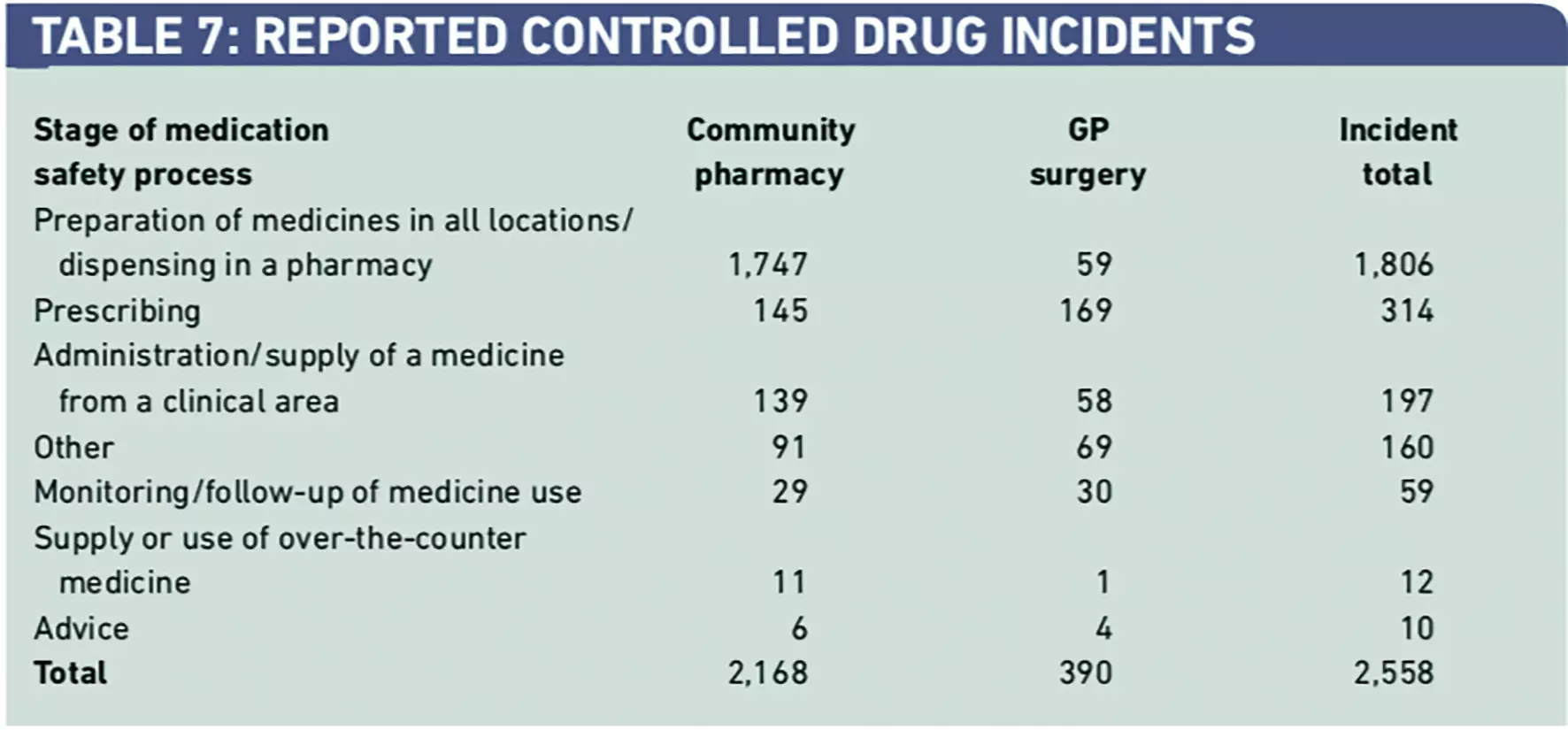

From the total of 72,028, only 2,558 reports (3.5 per cent) were from community pharmacy and general medical practice (Table 7). As expected, there was a dominance of dispensing incident reports. This relatively low incident reporting rates from primary care is consistent with our previous review of all medication incidents, indicating a poor safety reporting culture in this healthcare sector.1

Discussion

There is an important limitation to this study and that concerns our assumption that if the AO was not mentioned in the NRLS reports of serious harm arising from the use of CDs, then they were not informed of the incident and did not have the opportunity to review it and take the necessary actions to make local systems safer or suggest national action.

Similarly, we cannot confirm the validity of reports stating AOs were informed because there are no national data available to use for this purpose. In support of these assumptions there have been very few occasions when an AO has contacted the NPSA over the time frame of the study to raise concerns over risks or share learning concerning the safe use of CDs.

This review has several implications for practice:

- Unsafe use of CDs is the main cause of serious harm from medication incidents reported to the NRLS.

- In our view, better implementation of NPSA guidance could have prevented most of these incidents from harming patients. In particular all practitioners who prescribe, dispense or administer CDs should routinely confirm the intended dose is safe for the patient; for example, any new dose of diamorphine or morphine more than 50 per cent higher than the previous dose should be queried.

- Unsafe use of CDs is the main cause of serious harm from medication incidents reported to the NRLS.

- In our view, better implementation of NPSA guidance could have prevented most of these incidents from harming patients. In particular all practitioners who prescribe, dispense or administer CDs should routinely confirm the intended dose is safe for the patient; for example, any new dose of diamorphine or morphine more than 50 per cent higher than the previous dose should be queried.

- In our opinion prioritising efforts on safe custody and documentation of CDs may distract from ensuring the safe use of these potent medicines.

- Improvements are required to ensure more reporting of and learning from CD incidents in primary care.

- The role of the AO for CDs should prioritise reporting and learning of incidents that have caused serious harm.

- For reasons of improving the focus on the safe clinical use of CDs, transparency and quality improvement, we recommend an annual report is produced by individual AOs that summarises serious harms that have arisen from the use of CDs and the actions that have been taken to make the systems of use safer, to minimise these risks in the future. The report should also include a review of the use of antidotes naloxone, and flumazenil.9 These reports can be shared with the NRLS for national learning.

- A clinical subgroup to promote safer clinical use of CDs has been established to report to the National Care Quality Commission Accountable Officers for Controlled Drugs Group.

About the authors

David Cousins, PhD, FRPharmS, is senior head, safe medication practice and medical devices, David Gerrett, PhD. MRPharmS, is senior pharmacist, safe medication practice and medical devices, NHS England, and Bruce Warner, DPharm, MRPharmS, is deputy director of patient safety, all at NHS England.

Correspondence to: David Cousins (email: dcousins@nhs.net)

References

- Cousins D, Gerrett D, Warner B.Reporting and Learning System in England and Wales over six years (2005–2010). British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2012;74:597–604.

- National Patient Safety Agency. Safer Practice Notice. High dose morphine and diamorphine injections. 2006. Available at: www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk (accessed 22 August 2013).

- National Patient Safety Agency. Rapid Response Report. Reducing dosing errors with opioid medicines. 2008. Available at: www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk (accessed 22 August 2013).

- National Patient Safety Agency. Rapid Response Report. Reducing the risk of overdose of midazolam injections in adults. 2008. Available at: www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk (accessed 22 August 2013)

- National Patient Safety Agency. Rapid Response Report. Safer ambulatory syringe drivers. 2010. Available at: www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk (accessed 22 August 2013).

- National Prescribing Centre. Handbook for Controlled Drugs Accountable officers in England. Manchester: NPC, 2011.

- The Shipman Inquiry Fourth Report — The Regulation of Controlled Drugs in the Community. Available at: www.shipman- inquiry. org.uk/fourthreport.asp (accessed 22 August 2013).

- National Patient Safety Agency. The seven steps to patient safety. London: NPSA, 2004. Available at: www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk (accessed 22 August 2013).

- Classen DC, Lloyd RC, Provost L, et al. Development and evaluation of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Global Trigger Tool. Journal of Patient Safety 2008;4:245–9.

You may also be interested in

‘It just wasn’t viable’: the safety crisis facing patients with sensory impairments

Pharmacists cut medication errors and costs on diabetes and endocrinology wards, study results show