Introduction

In recent years a number of Department of Health policy documents have outlined the areas where pharmacists contribute to public health.[1],[2]

Smoking cessation advice is an example of where community pharmacist involvement in public health and health promotion has been successful. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence has described the provision of nicotine replacement products over the counter as effective and cost-effective.[3]

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society has encouraged pharmacists to advise clients on the correct use of nicotine replacement therapy[4]

and the availability of non-prescription nicotine replacement products has created a unique opportunity for pharmacists to identify and help smokers who want to quit.

Islington Primary Care Trust has been running patient group directions for nicotine replacement therapy for local community pharmacists since 2000.[5]

The PCT has 35 registered PGD pharmacists who offer stop smoking advice and supply nicotine replacement therapy to smokers who want to quit. However, there is considerable variation among pharmacists in the quit rates.

Some pharmacists have high success rates in supporting clients who want to quit, but others have a high lost-to-follow-up rate and far fewer clients who stop smoking. Some pharmacists recruit a significant number of clients, while others recruit only a few.

This study examines the current practices of community pharmacists in providing smoking cessation advice and explores why they take different approaches to recruiting clients and how this affects outcomes. One aim is to improve pharmacy-based smoking cessation services by developing a clear understanding of current practice and outcomes. Another is to ascertain how pharmacists recruit smokers to smoking cessation programmes. Our literature review has indicated a gap: no studies look at how pharmacists identify and approach smokers or how they discuss smoking with clients. Most studies have used quantitative methods. This research uses qualitative and quantitative methods.

Method

Qualitative and quantitative methods were used in two stages. At the first stage a small-scale quantitative survey was distributed by way of a questionnaire to local pharmacists to gain a broader understanding of the current practices on providing smoking cessation advice. At the second stage the approach was qualitative, with focus group interviews conducted to explore how and why pharmacists engage clients on the topic of smoking and how they continue to provide advice on giving up.

Of 45 community pharmacists in Islington, 35 were working under the PGDs for nicotine replacement therapy. The sample for the questionnaire consisted of 27 pharmacists selected from the smoking cessation service database.

A purposive sampling method for the questionnaire was adopted to include those trained locally by the PCT and using the evidence-based protocol to provide smoking cessation advice for two years. The eight pharmacists who were not included have been providing the stop smoking service for less than two years.

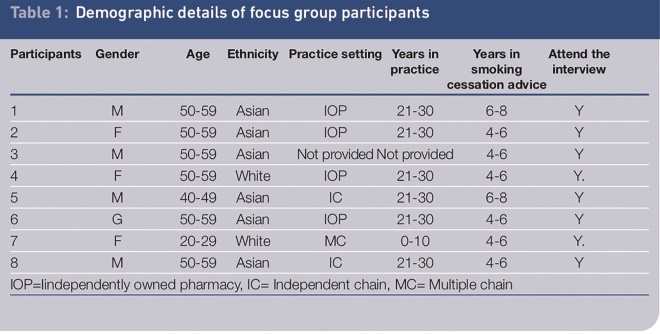

The focus group participants (Table 1) were selected by using a convenience sampling strategy with purposive underpinning. All 27 pharmacists received the questionnaire and were given the opportunity to take part in the focus groups. The 11 pharmacists who responded were invited to the focus group.

Table 1: Demographic details of focus group participants

The researcher was careful to draw participants from a range of different practice settings to ensure that the cases selected were information-rich and could yield an in-depth of the pharmacists’ interactions.[6]

Data collection methods

Questionnaire

A self-administered, structured questionnaire was used to collect demographic data on pharmacists and gain a snapshot view of current practice on smoking cessation advice. The results informed the planning of the focus group interviews. The questionnaire was piloted by three pharmacists who did not take part in the final study.

Focus group interviews

The focus group was chosen to explore the reasons for differences in approaches to recruitment and outcome of smoking cessation advice, since using a focus group has been shown to be an effective technique for exploring the attitudes and needs of staff.[7]

Pharmacists were allocated to one of two focus groups according to the best spread of differences in terms of practice settings. Eight out of 11 pharmacists attended the groups, both of which were given the same instructions and considered the same scenarios.

The topic guide (Panel) was informed by the results from the questionnaire and a preliminary analysis of the literature and comments by PCT staff who work closely with community pharmacists. The topic guide started with a vignette and was loosely structured to stimulate discussion, since the researcher/moderator sought group interaction rather than answers to questions.[8]

The guide was used in a way that allowed a full range of views to be voiced within the group.

Panel: Focus group topic guide

Vignette

Scenario 1: A man aged 50 says that his cough has got worse and he wants to buy cough medicine.

Scenario 2: A women aged 20 comes to the counter to pay for some beauty products.

For each scenario (written on cards), please discuss,

- How is the client identified as being a smoker?

- How is smoking advice initiated?

- How is stop smoking advice concluded?

Group discussion

What strategies do you use to get agreement on a stop date?

What happens when they agree to a stop date? Stop smoking advice (behavioural support and medications)

Having been providing smoking cessation advice for some time, do you see yourself as successful in terms of quitter outcomes?

- If yes, why? If no, why not?

- What would help you to become more successful?

- Do you think it would be acceptable to clients for you not to initiate stop smoking advice?

Data analysis

An inductive method was employed to analyse the transcripts of focus group data and thematic analysis was used to summarise the main issues emerging from the data. Focus group interviews were transcribed verbatim.

Close attention was paid to producing detailed data, as representative as possible of the experiences of pharmacists, and to leaving a trail of data analysis that another researcher could easily follow and reanalyse.

The questionnaire data were studied and areas that appeared significant were highlighted. Data from the questionnaire and focus group interviews were triangulated to ensure the findings were comprehensive rather than to test their validity.[9]

Verbatim quotes from group interviews and data from the questionnaire were presented in an integrated fashion according to the emergent themes.

To avoid bias the transcripts of focus group 1 were read and themes compared by another researcher who identified similar codes and themes.

Results

A total of 320 codes were created by analysing the data from the two focus groups and were assigned to 24 categories, resulting in the identification of five themes:

- Identifying smokers

- Initial approaches to smokers

- Preparing to quit

- Pharmacists’ perceptions of success

- Pharmacists’ perceptions of clients’ views

The results from the questionnaire were placed under the relevant themes. Most results overlapped with results from the focus groups.

Identifying smokers

Identifying smokers is the most important step for pharmacists. In both sets of focus group interviews, pharmacists appeared to be confident in identifying a smoker when the person had a cough:

You know we’ve been doing this for years, we pick up, that’s how we approach, yes, we can alleviate the cough.

Pharmacists came up with a variety of identifiable signs that should encourage them to approach a customer:

You can see coloured fingers … even the smell sometimes … even the body language tells, the texture of the skin …

All pharmacists find it difficult to identify and approach smokers about quitting when there is no identifiable sign. When pharmacists were asked how they can identify a smoker in the case of a young woman buying beauty products all agreed that it would be difficult:

This one is tricky because you can’t just approach somebody who is buying beauty products, and say — hey, do you smoke?

Almost half of the pharmacists indicated on the questionnaire that not wanting to be seen as intrusive is one of the main difficulties in initiating smoking cessation advice. Two respondents answered the question “What do you think are the main difficulties in initiating smoking cessation advice?” by saying “bringing up the topic when it may not be related to a current discussion might be intrusive” and “telling people about the long-term benefits, especially when they tell you they enjoy smoking”.

Some pharmacists in focus groups have moved away from the feeling of being intrusive. They approach their customers confidently to offer help:

I have found with us being identified as healthcare professionals … people are more receptive … we don’t feel we are intruding … we’re not prying… . We’re asking this because there is a place where we can help.

In the questionnaire, when they are asked about the main difficulties of initiating smoking advice most pharmacists disagree that lack of knowledge and skills is one of the barriers. More than half of the pharmacists indicated that they did not want more training. Most of the pharmacists did not see how training might have a positive effect on their approach to smokers.

Initial approaches to smokers

Purchase of over-the-counter nicotine replacement therapy was seen as an opportunity to inform smokers about the service:

Because we pick quite a lot of people up when they are buying them anyway, we mention that we have this service and ask if they would like some extra help.

However, the questionnaire data showed inconsistencies among pharmacists. A few pharmacists rarely discuss smoking with clients who buy nicotine replacement therapy over the counter: between a quarter and a third of pharmacists are failing to use the easiest of opportunities to initiate a discussion on smoking. One of the reasons for this might be that pharmacists are not always aware of when non-prescription nicotine replacement products are purchased.

In the questionnaire more than half of respondents agreed that lack of time was one of the main obstacles to initiating smoking cessation advice. Three respondents said trying to engage in a conversation when busy dispensing is one of the aspects of providing smoking cessation advice that they least enjoy.

Some pharmacists answered the question “What aspects of providing smoking cessation advice do you least enjoy?” by identifying the paperwork. Some respondents suggested that reducing paperwork and having electronic resources might improve pharmacy-based smoking cessation services.

Pharmacists highlighted the fact that pharmacy assistants are often the first point of contact for smokers. Therefore they have a key role in informing smokers about the service and recruiting interested smokers to the service. They could also be trained to provide one-to-one stop-smoking advice. Some said it is an advantage that the pharmacy assistants have good links with the local community:

It is the staff who are the first contact they will have, and if the staff have been there for a long period it is a social thing for them.

Preparing to quit

All pharmacists in the focus groups recommend that their clients set a target date to quit. They believe preparation is crucial if clients are to attend treatment sessions. They feel strongly that spontaneous decisions may result in clients never showing up:

“I’m going to give up tomorrow.” It doesn’t really work because they are desperate to give up. They do that for a short period and they are back on to it.

Most of the pharmacists seemed to respect differences between individuals by adjusting the level or amount of information provided. They take the lead from clients and tailor advice according to their different needs. Some found they learn more about clients by letting them talk and by listening:

What I have found is you have to react to each patient accordingly, give them a small amount of information, but let them do a lot of talking back. It is letting the client do a lot more talking and then trying to answer some of their questions.

Some pharmacists claimed that GPs often put pressure on smokers and this can go as far as doctors threatening to cease a patient’s treatment.

Actually, the doctor put a bottom line to him … so the doctor said:“We’re not going to treat you until you give up smoking.”

Pharmacists believe that a GP’s authoritative style may damage the patient–pharmacist relationship:

We did the carbon monoxide and everything, and I could see he’s not willing to give up. But I said: “Look, come back later.”“No, my doctor has said I have to stop today, so I’m going to stop today.” So I said:“I would still like you to go home, think about it.”“If you don’t give me anything, then, if something happens to me, it’s going to be your fault because the doctor has told me to stop smoking today.”

Pharmacists’ perceptions of success

Overall, participants feel successful in achieving four-week quitters as defined by the Department of Health.[10]

They evaluate their success by considering their relationship with their clients. For example when confidence improves and clients return to the pharmacy that is viewed as a successful outcome:

We had one who came in last week. She gave up and must have started smoking again. I didn’t realise that, but she walked in and she still had the confidence to come into the shop and that shows that it’s working.

The relationship between job satisfaction and quitting success was highlighted. One pharmacist claimed that the quality of service provided is important because it increases job satisfaction. Job satisfaction is also linked to a client’s satisfaction:

With experience, I have learnt that quantity is not what it is, and it is the kind of quality that we can put out now. Therefore, I am not going for quantity but quality, and that way I find satisfaction in my work. I am sure if that is happening, clients are finding it satisfying as well.

In the questionnaire respondents gave similar answers to the question “What aspects of providing smoking cessation advice do you most enjoy?” Supporting, motivating, helping and counselling clients, customer interaction, job satisfaction, achieving positive outcomes and quitters were among the most common answers.

Helping smokers to reduce the number of cigarettes that they smoke is overwhelmingly seen as a measure of success. It was also highlighted that reducing smoking was a considerable achievement for some clients.

To even get people to reduce is probably quite an achievable aim, and one may be able to get more people on board.

Some pharmacists used cutting down cigarettes both as a strategy to get people to start thinking about stopping and as a measure of success:

“Even if you don’t want to stop altogether, at least start reducing.” I believe that idea of reducing makes them start thinking.

Pharmacists’ perceptions of clients’ views

The results suggest that some pharmacists believed high levels of client appreciation of pharmacists’ interventions were achieved:

They appreciate the service long after they have given up smoking. They remember and remind you of that.

Pharmacists feel that some clients use pharmacists for non-drug related counselling and support:

We have had people who have had prescriptions from GPs for products, but they still like to come to us, talk to us, for us to do their carbon monoxide, and they want to discuss it with us. They bring the prescription, so we do not dispense the product, but they want to talk.

The accessibility of pharmacists compared with GPs and other stop-smoking services were seen as a major strength by all pharmacists. They believed that clients were highly appreciative of the flexible hours, instant access and the drop-in service:

They can come to you and talk to you within a short space of time. If they go to a GP surgery, they have to make an appointment and they have to take a time off.

GPs are associated with sickness. Smokers do not necessarily see themselves as unhealthy, therefore attending a GP surgery to give up smoking might not appeal to them. One respondent said:

A lot of these are healthy people, so they don’t access GP services, they don’t really go there, so we are key people that they access, in healthcare. That is where I passionately believe that pharmacists have a very good role to play.

If pharmacists do not provide smoking cessation services, smokers will have to populate other services and, as a result, there might be longer waiting lists. Pharmacists think this will not be acceptable to smokers:s

If the pharmacy service were to be removed, it creates a gap and it puts an extra burden on the other people who were providing the service.

Discussion

Identifying smokers

This study suggests that pharmacists think that they can easily identify smokers when there are signs such as coughing or stained fingers. Without such signs pharmacists find it difficult to intervene.

Raising health promotion issues with most clients was seen as problematic, because the pharmacist had no way of knowing who might appreciate the advice and who might be offended.[11]

It was claimed that not routinely identifying patients who smoke was a significant barrier in providing effective smoking cessation services.[12]

Pharmacists in this study believe they have the knowledge and skills to provide smoking cessation advice and therefore they do not need more training. However, Maguire[13]

found that many pharmacists failed to appreciate that they need to develop new skills and that reluctance on the part of some pharmacists to open dialogues with pharmacy users about smoking can be improved by training. The evidence suggests that pharmacists feel more comfortable asking questions and providing information on sensitive issues after they have received training.[14]

There seems to be a dilemma for pharmacists: on the one hand they are anxious not to alienate customers and on the other they want to help smokers to quit. Pharmacists need to remember that some customers who are buying cosmetics, or other goods, may have little contact with their GP and may not be aware of smoking cessation services; pharmacists may be their only contact with a health professional and this could be their only chance of getting help to quit smoking.

Offering brief advice and information about new treatments, without necessarily entering into an in-depth debate about smoking, is more effective than saying nothing according to NICE.[15]

West and Sohal highlight the fact that a substantial proportion of quit attempts are unplanned[16]

and pharmacists are well placed to capitalise on this.

Initial approaches to smokers

Pharmacists might be the only healthcare providers with an opportunity to help smokers to stop smoking due to the increased availability of non-prescription nicotine replacement therapy products.[12],

[17]

In this study some pharmacists use every opportunity to broach the subject of smoking, while others do not use the purchase of nicotine replacement therapy as an opportunity to engage smokers in conversation. This should be taken seriously by the pharmacy profession, local pharmaceutical committees, smoking cessation service managers and facilitators. Opportunistic advice at the point of sale is one of the strengths of pharmacy, and pharmacists should not miss the opportunity to make a difference to people’s health.

Lack of time was reported as the most important barrier to asking customers whether they smoke. This is no surprise, since the current dispensary-based remuneration framework takes a substantial amount of time. The NHS pharmacy contract[18]

is set to change this by rewarding the quality of work, including public health work as a core activity.[19]

The results are yet to be seen. However pharmacists need to realise that time will continue to be a pressure.

Pharmacists highlighted the large amount of paperwork they have to complete and suggested replacing paperwork with electronic resources. Some primary care trusts have invested in web-based information systems for collecting data. Such systems can be of great benefit to commissioners and can reduce the amount of paperwork that needs to be completed by community pharmacies. They can be a worthwhile investment, improving timeliness of reporting and data completeness, and reducing duplication.

The findings reveal that some pharmacists may not be aware when non-prescription nicotine replacement therapy is purchased. This ties in with the fact that 90 per cent of medicine sales were made by counter staff.[20]

Pharmacists participating in the focus group said that pharmacy assistants are often the first point of contact for smokers, therefore they could initiate smoking advice.

There is some evidence from a US study that where dispensing technicians record smoking status and are involved in interventions, the numbers of interventions are roughly double those in pharmacies that do not involve technicians.[21]

Further research is needed on the relationship between pharmacy assistants and customers and their role in smoking cessation; there is potential benefit to be gained from a whole-staff approach in community pharmacy.

Preparing to quit

The findings show that pharmacists encourage smokers to set a quit date, plan and then try to quit. Pharmacists believe that spontaneous decisions are not necessarily an indication of how serious smokers are in their quit attempts.

Some recent research suggests that quitting without planning is the norm,[16]

but in his book West[22]

suggests that the human mind is unstable and sensitive to small events and triggers. These small triggers might create substantial changes in behaviour patterns. This suggests a discrepancy between current practices and the latest evidence. Pharmacists need to be made aware that some smokers may not need a long preparation stage before the quit date.

The focus groups showed that pharmacists’ communication skills were moving towards patient-centredness. Counselling skills, such as active listening, help clients to identify aspects of their situation that are harmful to their health.[23]

Some pharmacists claimed that by allowing clients to talk they learn more about them.

Pharmacists claimed that GPs put pressure on patients who have smoking-related diseases to give up smoking. This can include threatening to stop treating them if they do not quit. This type of approach is not noted for its success and can irritate patients.[24],[25]

Such attitudes from GPs could have a negative impact on the pharmacist-patient relationship. The primary care trust must ensure that GPs are making appropriate referrals to pharmacy-based smoking cessation services and that smokers have a clear understanding of what to expect when they see a pharmacist.

Pharmacists’ perceptions of success

It seems that returning clients and job satisfaction represent success. This result can be linked with “reprofessionalisation”. The evidence shows that pharmacists feel dissatisfied with a straightforward dispensing role and believe closer involvement with patients make their work more interesting.[26]

Smoking cessation provides opportunities beyond handling medicines. Returning clients might be associated with pharmacists having their own clientele by registering smokers to the programme, building up a relationship and having continuity of care.

Edmund and Calnan showed that pharmacists are in favour of patients regularly using the same pharmacy, since this enhances patient care.[26] This finding could be useful for service managers and commissioners in their negotiations with the local pharmaceutical committee to get pharmacists involved in smoking cessation.

Pharmacists in this study use reducing smoking as a strategy to get their clients interested in stopping smoking and as a measure of success. Current NICE guidelines[3]

recommend that stop smoking treatments, such as nicotine replacement therapy are for stopping only. However, new research shows that smokers who use nicotine replacement therapy to cut down with a view to quit increase their chances of stopping smoking altogether.[27]

Evidence suggests that smokers from deprived communities are highly addicted to cigarettes. Although they are motivated they find it difficult to stop smoking and therefore need more intensive support for longer.[28]

Since community pharmacists serve local communities and have the potential to reach smokers from disadvantaged groups, reducing smoking with a view to quitting can be one way of improving pharmacy-based smoking cessation. Further research is needed.

Pharmacists’ perceptions of clients’ views

The findings show that, overall, pharmacists believe that clients value the stop-smoking services offered by pharmacists. These findings are in line with evidence that pharmacy users value advice and services from community pharmacists and demonstrate a high level of user satisfaction.[19]

Evidence suggests that the use of pharmacy for general advice is still low.[29]

However, the experience of service users appears to be more positive.[30]

Our results confirm this, as pharmacists have sensed that clients are beginning to use pharmacists for non-drug related services.

People living in areas of deprivation, high unemployment or inner cities are more frequent users of community pharmacies.[30]

In the light of these findings it is evident that clients view pharmacy as a convenient place to receive smoking cessation advice. If the gap in health inequalities caused by smoking is to be reduced then commissioners should invest in pharmacy-based smoking cessation.

The findings from the focus group show that pharmacists believe their services are more accessible than GP services. Other evidence supports these findings.[31],[32]

Moreover, pharmacists are aware that they have access to healthy people as well as ill people.

Smokers might not see themselves as unhealthy and might not seek help to give up smoking unless they see a sign of ill-health. This strengthens the role of pharmacists, as the only health professionals who have a potential to access these smokers.

Pharmacists have been providing smoking cessation services for almost 10 years, along with services, such as emergency hormonal contraception, drug misuse and sexual health. While the advice-giving role of the pharmacist still needs to be promoted, more studies are needed to determine whether there has been any shift in the views of pharmacy users.

Pharmacists believed that if they did not provide smoking cessation services this would be unacceptable to smokers as their access to help would be limited; it would also be unacceptable to other providers because it would increase their workload.

Limitations of the study

This study was a small-scale research project related to a specific context and did not aim to produce findings that are generally transferable. But there is no reason to suppose that the pharmacists in the study group differed in any major way from other pharmacists running smoking cessation services in similar areas. In terms of the characteristics of pharmacists running cessation services those on the Islington smoking cessation service database are fairly typical of pharmacists in similar boroughs.

The participants who volunteered for the focus group interview may not be representative as they may be interested in developing pharmacy-based smoking cessation and therefore keen to contribute to the study.

The focus groups were structured and conducted in a way that ensured that important questions, which had emerged from the questionnaire data and literature review, were covered. The structure was flexible enough to allow pharmacists in the groups to raise issues that were important to them.

The researcher has been managing stop smoking services in Islington, therefore respondent bias could have taken the form of being obstructive, as the researcher might be seen as a threat. However, since the researcher has been involved in the service over a long period of time, a trusting relationship between the pharmacists and the researcher has been built and consequently reactivity and respondent bias reduced.[33]

On the other hand some pharmacists might have tried to give the answers they think the researcher wanted to hear. Focus groups, rather than individual interviews, were chosen to reduce respondent bias.

Conclusion

Community pharmacy is seeking to enhance its professional status through reprofessionalisation — by moving beyond dispensing and towards more clinical activities. Smoking cessation is one of the strategies for reprofessionalisation and could represent a bridge to future public health practice.

The findings from this small-scale study are not generalisable. However they do have important implications for current pharmacy-based smoking cessation services. The in-depth exploration provided a greater understanding of pharmacists’ approaches to recruitment of smokers, including some direction on ways to overcome barriers to initiating smoking advice. The findings can also be used to improve pharmacy-based public health interventions other than smoking cessation.

Recommendations:

Based on these findings the following recommendations will be made to Islington PCT:

Training

Training, especially in behaviour change methods, was found to be essential to the success of pharmacy stop-smoking services. The principles of any training for pharmacists should be to aim to utilise the skills unique to them, to address their needs and be linked to their continuing professional development. They need to be identify smokers easily, approach them confidently and offer help based on the need of the individual smoker.

Mechanisms for ongoing support and follow-up should be built into the training programme, because pharmacists need help to translate learning into practice and to build their skills and experience.

Training must provide practical approaches for implementing brief interventions in busy community pharmacies by using experiential learning tools such as role play, case studies and scenarios. Pharmacists who are experienced and confident in providing smoking cessation interventions could be used as peer educators to support others. Shadowing and session observation that includes providing feedback could be considered.

The knowledge base among community pharmacists in relation to nicotine replacement therapy and smoking cessation seemed to be good. Therefore annual update training focusing on new developments in the field of smoking cessation should be sufficient.

Whole pharmacy approach

Central to overcoming some of the barriers, such as time, and not knowing when nicotine replacement therapy is purchased is a whole-pharmacy approach. As the first point of contact with smokers, pharmacy assistants should be trained to ensure they have the skills needed to carry out interventions.

Electronic resources

There is a need to create time for pharmacists through the use of new technologies that minimise paperwork. The primary care trust should urgently invest in the development of electronic recording of data to assist pharmacists practising smoking cessation interventions.

GP referrals

GPs need to refer smokers appropriately: that means ensuring that smokers have a clear understanding of what to expect when they see a pharmacist. The PCT’s prescribing advisers and stop-smoking team members should promote pharmacy-based smoking cessation to GPs.

Research

There is a need for a qualitative study on smokers’ perceptions of stop-smoking advice from community pharmacists which show a client’s journey, starting from the initial recruitment to post-quit support at the end.

There is a need for research on the relationship between pharmacy assistants and pharmacy customers and assistants’ role in smoking cessation.

About the authors

Seher Kayikci, MSc was smoking cessation and prevention manager at NHS Islington Public Health Department.

Susie Sykes, MA, is public health and health promotion at South Bank University

Correspondence to: Seher Kayikci (email seher.kayikci@gmail.com)

References

[1] Department of Health. Pharmacy in the future: Implementing the NHS Plan. London: HMSO; 2000.

[2] Department of Health. A vision for pharmacy in the new NHS. London: HMSO; 2003.

[3] National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Guidance on the use of Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT) and bupropion for smoking cessation. London: NICE; 2002.

[4] Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. Pharmacy in a new age. London: RPSGB;1999.

[5] Islington Primary Care Trust. Patients Group Directions for Nicotine Replacement Therapy. London: Islington PCT; 2000.

[6] Patton M. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. California: Sage; 2002.

[7] Kitzinger J. Focus groups with users and providers of health care. In Pope C and Mays N (editors). Qualitative Research in Health Care (2nd ed). London: BMJ Books;2000.

[8] Bloor M, Frankland J, Thomas M, Robson K. Focus Groups in Social Research. Sage Publications; 2002.

[9] Mays C, Pope N. Rigour and qualitative researcher. BMJ 1995;311:109–112.

[10] Department of Health. NHS Stop Smoking Services Monitoring Guidelines. London: HMSO; 2001.

[11] Hughes K. Pharmacists and contraceptive and sexual health issues: qualitative research to inform barriers and opportunities. London: Health Education Authority; 2000.

[12] Aquilino ML, Farris KB, Zillich AJ, Lowe JB. Smoking cessation services in Iowa community pharmacies. Pharmacotherapy 2003; 23:666–73.

[13] Maguire TA. Pharmacy smoking cessation services: let’s get our act together! The Pharmaceutical Journal 2000;265:442.

[14] Anderson C, Blenkinsopp A. Bissell P, Armstrong M. The contribution of community pharmacy to improving the public’s health. Report 4: Local examples of service provision 1998–2002. London: RPSGB/PHLink; 2005.

[15] National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Brief interventions and referral for smoking cessation in primary care and other settings. London: NICE; 2006.

[16] West RD, Sohal T. “Catastrophic” pathways to smoking cessation:findings from national survey. BMJ 2006;332:458–60.

[17] Hudmon KS, Prokhorov AV, Corelli RL. Tobacco cessation counselling: Pharmacists’ opinions and practices. Patient Education and Counselling 2006;61:152–60.

[18] Department of Health. The new contractual framework for community pharmacy. London: HMSO; 2004.

[19] Armstrong M, Lewis R, Blenkinsopp A, Anderson C. The contribution of community pharmacy to improving the public’s health. Report 3: an overview of evidence-base from 1990-2002 and recommendations for action. London: RPSGB/PHLink; 2005.

[20] Ward PR, Bissell P, Noyce PR. Medicines counter assistants: role and responsibilities in the sale of deregulated medicines. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 1998;6:207–15.

[21] Purcell J, Farris K, Aquilino ML. Feasibility of brief smoking cessation intervention in community pharmacies. Journal of American Pharmacists Association 2006;46:616–8.

[22] West RD. Theory of Addiction. Blackwell Publishing; 2006.

[23] Cribb A, Dines A. Health Promotion: Concepts and Practice. Blackwell;1994.

[24] Stott NCH, Pill RM. ‘Advice yes, dictate no.’ Patients views on health promotion in the consultation. Family Practice 1990;7:125–31.

[25] Butler CC, Pill P, Stott NCH. Qualitative study of patients’ perceptions of doctors’ advice to quit smoking: implications for opportunistic health promotion. BMJ 1998;316:1878–81.

[26] Edmunds J, Calnan MW. The re-professionalisation of community pharmacy? Social Science and Medicine 2001;53: 943–55.

[27] ASH (Action on Smoking and Health) Nicotine Assisted Reduction to Stop (NARS): guidance for health professionals on this new indication for nicotine replacement therapy. London: ASH; 2005.

[28] ASH (Action on Smoking and Health) ASH Research Report on Smoking and Health Inequalities. London: ASH; 2001.

[29] BRMB. Baseline mapping study to define access to and usage of community pharmacy. Report commissioned by Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain;1996.

[30] Blenkinsopp A. Anderson C, Armstrong M. The contribution of community pharmacy to improving the public’s health. Report 2: evidence from the UK non peer-reviewed literature 1990–2002. London: RPSGB/PHLink; 2003.

[31] Anderson C, Blenkinsopp A, Armstrong M. The contribution of community pharmacy to improving the public’s health. Report 1: evidence from the peer-reviewed literature 1990-2001. London: RPSGB/PHLink; 2003.

[32] National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Research to explore training programmes in smoking cessation for pharmacists and pharmacy assistants. London: NICE;2005.

[33] Padgett DK. Qualitative methods in social work research: challenges and rewards. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage; 1998.