Abstract

Aim

To identify and describe governance and performance management activity in primary care trusts in England relating to the provision of pharmaceutical services.

Design

A self-completion questionnaire.

Subjects and setting

All PCTs in England.

Results

The response rate was 74%. 55% of PCTs knew the names of clinical governance leads for all community pharmacies in their locality. Respondents estimated that, by the end of June 2006, 55% of community pharmacies would have been visited to monitor attainment or maintenance of essential service specifications and clinical governance requirements. National templates have been produced for 10 of the 19 enhanced services, but use of these has so far been low. Training and accreditation requirements and the setting of targets for service activity levels both varied considerably between individual enhanced services and PCTs.

Conclusions

Progress on monitoring the new contract for community pharmacy has so far been variable and many pharmacies have still not received a monitoring visit.

Setting standards and monitoring performance activity are central to the delivery of quality and equitable health services. Clinical governance was introduced through NHS policy in the late 1990s as part of a wider agenda to improve quality within the NHS. The clinical governance framework was designed to guarantee that minimum standards of care were met and to promote continuous improvement.1

Following the publication of “A first class service: quality in the new NHS”,2 which set out the proposed clinical governance framework, resources were made available to assist NHS organisations to execute their clinical governance function. With relation to pharmacy policy, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society published its strategy for clinical governance in pharmacy.3 “Pharmacy in the future” then made recommendations to support clinical governance in community pharmacy4 and pledged to encourage and reward quality pharmacy services, and the Department of Health published guidelines for implementing clinical governance in community pharmacy.5 The strategy required primary care trusts to fulfil a number of actions by April 2002, including identifying a PCT community pharmacy clinical governance lead and ensuring that clinical governance requirements were built into services commissioned locally.

Thus, before the new contractual framework for community pharmacy was introduced, PCTs were already responsible for certain clinical governance functions, but there were no official requirements for community pharmacies to participate in the arrangements, although voluntary activity was encouraged. Clinical governance has continued to evolve and respond to developments in the wider health agenda such as the focus on a patient-centred NHS. Strategies such as “Building a safer NHS for patients”6 make clear a requirement for professionals to be accountable for their work.

More recently, the new national contractual framework for community pharmacy sets out requirements for all essential and advanced services via the service specifications. The contract is supported by a clinical governance infrastructure which underpins the provision of all services. This framework incorporates a number of components, including the requirement that every community pharmacy must have an identifiable clinical governance lead.

PCTs have had responsibility for monitoring the implementation of essential and advanced services since 1 October 2005. This is usually expected to be carried out through an annual visit to each community pharmacy. The NHS Primary Care Contracting team produced a guide to assist PCTs undertaking these “monitoring visits”.7 National templates have been developed to assist PCTs with the process of commissioning services locally through the enhanced services tier. These templates provide service descriptions and aims and suggest appropriate quality indicators, but do not specify standards. They exist for PCTs either to follow, or to adapt as appropriate when commissioning services locally. To date, templates have been developed for 10 of the 19 enhanced services.8

The aim of this paper is to identify and describe governance and performance management activity in PCTs in England relating to the provision of pharmaceutical services. Training and accreditation requirements for the providers of services and the setting of targets for service activity levels were used as indicators of clinical governance activity and performance management activity.

Method

A questionnaire about the commissioning of community pharmacy services was sent to all PCTs in England in March 2006. Detailed descriptions of the research method, sample and topics covered have been provided previously.9

This paper presents findings from the questionnaire relating to clinical governance and performance management activity. Respondents were asked to state the number of community pharmacies for which the name of the clinical governance lead was known to the PCT and the number visited to monitor attainment or maintenance of essential service specifications and clinical governance requirements. Figures for the monitoring visits were collected at three different points in time — the end of December 2005, the end of March 2006 and the end of June 2006. The survey was distributed in March, so responses to these questions were based on visits that had taken place, as well as the number of the visits that the PCT planned to undertake at a future date (some of the March figures and all of the June figures).

For each enhanced service commissioned, respondents were asked to state whether the national template had been used. Details were also collected on whether service providers were required to undertake training, needed to be accredited or assessed, and whether targets for service activity levels had been set for each service.

Data were entered into SPSS v13.0 for analysis and explored using frequency counts and basic descriptive statistics.

Results

Two hundred and sixteen PCTs returned completed questionnaires, giving a response rate of 74 per cent.

Monitoring essential and advanced services

In total, the names of 5,324 community pharmacy clinical governance leads (70 per cent) were known to PCTs. One hundred and thirteen PCTs (54.9 per cent) knew the names of the clinical governance leads for all community pharmacies in their locality, while 23 (11 per cent) knew none.

By the end of December 2005, a total of 591 community pharmacies across all respondent PCTs (8 per cent) had been visited to monitor attainment or maintenance of essential service specifications and clinical governance requirements. Respondents estimated that by the end of March 2006 the figure would be 2,362 (31 per cent) and, by the end of June 2006, 4,168 (55 per cent).

In terms of PCT monitoring activity, eight PCTs (4 per cent) had visited all their local community pharmacies by the end of December 2005. The figures for March and June 2006 were 42 (20 per cent) and 94 (44 per cent), respectively. At the end of December 2005, 174 PCTs (81 per cent) had not undertaken any monitoring visits. The estimated respective figures were 89 PCTs (42 per cent) for March 2006 and 37 (17 per cent) for June 2006.

Use and non-use of national templates for enhanced services

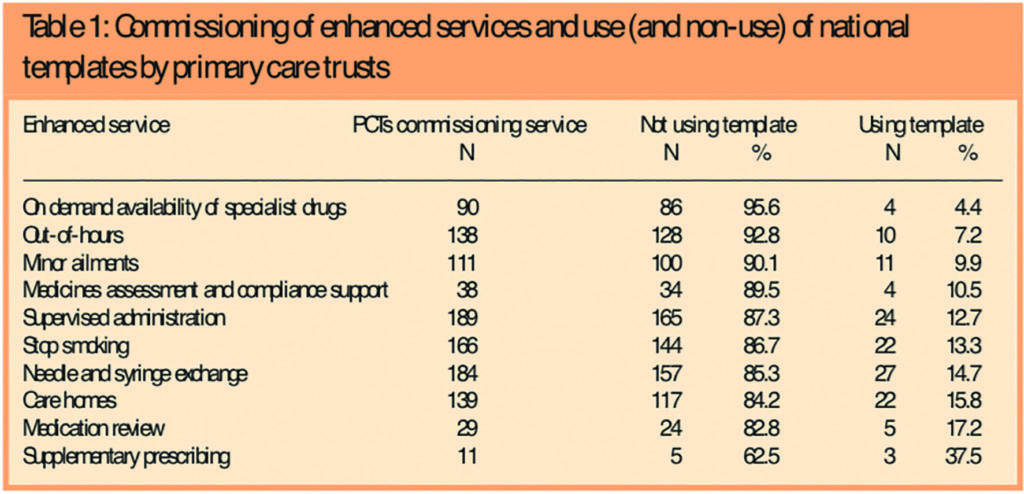

Table 1 shows the number of PCTs that had commissioned each enhanced service for which a national template was available, and the number of PCTs using and not using this.

Non-use of templates was high, with a mean figure across all services of 86 per cent. On-demand availability of specialist drugs services had the highest figure, with 96 per cent of PCTs not using the national template, while the lowest figure was for supplementary prescribing, at 63 per cent. The average number of these services commissioned per PCT was five, with a range of one to 10. The proportion of commissioned services for which a PCT had not used templates ranged from zero to 100 per cent and the mean was 78 per cent.

In general, the more commonly commissioned services had slightly higher levels of template use than the less frequently commissioned ones, with the notable exceptions being supplementary prescribing and medication review services, which were the least commissioned services, but with the highest proportions of PCTs using templates (27 per cent and 17 per cent, respectively).

Training, accreditation and target-setting for enhanced services

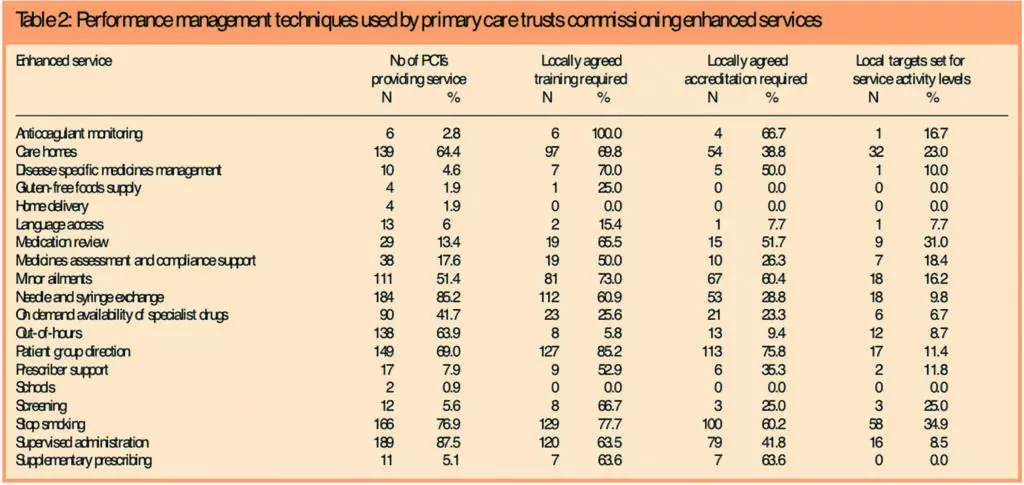

Table 2 shows the number and percentage of PCTs which had commissioned each of the 19 enhanced services, and the extent of use of locally agreed training for providers, accreditation of pharmacies and setting of service activity targets for each service.

Across all services, the average proportion of PCTs requiring providers to undertake local training was 56 per cent. The highest proportion (100 per cent) was found for anticoagulant monitoring.

On the whole, PCTs had fewer requirements for accreditation and assessment than for provider training, with a mean of 35 per cent across all services, while patient group directions (PGD) had the highest figure at 76 per cent.

Service activity level targets were not routinely set for the majority of commissioned enhanced services. The highest proportion was for stop smoking services, for which 35 per cent of PCTs had set targets (mean 14 per cent).

Across PCTs, the proportion of commissioned services for which PCTs required providers to be trained and accredited ranged between zero and 100 per cent, with the averages being 59 per cent and 41 per cent, respectively. The results of the survey showed that the setting of targets for service activity levels ranged from zero to 80 per cent, with an average of 15 per cent.

Training and accreditation requirements and the setting of targets for service activity levels varied between and within the 19 commissioned services. All services except home delivery and schools services had at least one of the three measures in place in some PCTs, but no service had consistent levels of all three in place.

Discussion

Progress on monitoring the essential services in the new contract for community pharmacy has so far been variable. Nine months after becoming responsible for monitoring the contract, most community pharmacy clinical governance leads had been notified to PCTs, and visits had been conducted at over half of all pharmacies within the respondent PCT areas. However, 3,406 pharmacies were yet to be visited, and 17 per cent of PCTs had not begun the process. Previously, we have reported that PCT capacity, in terms of staff numbers, was a major barrier to the commissioning of pharmaceutical services.10 As a result, commissioning staff may have found it difficult to meet the monitoring demands of the new contract. A comparison can be drawn with our findings and an earlier study of clinical governance in primary care, which identified a lack of sufficient staffing as a barrier to the successful implementation of clinical governance.11 The authors contend that effective management of new directives in health care do not happen quickly but need realistic timescales. PCTs have only been required to monitor the new contractual framework for community pharmacy for just over 10 months. Therefore there is considerable scope for monitoring and governance activity to develop over time as the new contract beds down.

National templates are available for 10 of the enhanced services, but their use so far has been notably low. However, as over 80 per cent of enhanced services currently being provided were commissioned before April 200512 and the templates were not produced until September 2005, this is perhaps not so surprising. Local training is required for over half of enhanced services commissioned by PCTs and accreditation of providers is also fairly common. However, the setting of targets for service activity levels is much more limited. Parallels can be drawn here with the local pharmaceutical services contract experience, where, although commissioners of LPS pilots were required to set targets for services in the contracts, most LPS pilot sites failed to meet their targets during the first 12 months of operation. Several PCTs commissioning services via the LPS contract had opted to shoulder the bulk of the financial risk for services.11 Although this survey did not address the ways in which targets had been set or how successfully they are being met, financial outlay remains a pertinent risk for PCTs when commissioning enhanced services in particular because, unlike for essential and advanced services, there is no central funding available.

Most enhanced-level services were commissioned before the implementation of the new contract.13 Generally, PCTs are more likely to require prior training and assessment of pharmacists and accreditation of providers for the services that are the most novel or involve the greatest risk. The level of inconsistency in commissioning criteria between PCTs, however, does raise questions about the quality assurance of enhanced-level services across England.

It is estimated that nearly half of community pharmacies still have to receive their first governance review related to the provision of essential services 15 months after the implementation of the new contract. Service targets have also not been set by most PCTs for the majority of enhanced-level pharmaceutical services.

Acknowledgements

We thank colleagues in PCTs who put significant effort into providing us with a huge amount of detailed data during a period of considerable turbulence. This study was funded by the Department of Health.

This paper was accepted for publication on 18 August 2006.

About the authors

Rebecca Elvey, MA (Econ), and Fay Bradley, MA (Econ), are research associates, Darren Ashcroft, PhD, MRPharmS, is director of the Centre for Innovation in Practice and Peter Noyce, PhD, FRPharmS, is professor of pharmacy practice at the University of Manchester.

Correspondence to: Rebecca Elvey, Centre for Innovation in Practice, The Workforce Academy, School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL (e-mail rebecca.elvey@ manchester.ac.uk).

References

- Department of Health. The new NHS, modern, dependable. London: The Department; 1997.

- Department of Health. A first class service: quality in the new NHS. London: The Department; 1998.

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Achieving excellence in pharmacy through clinical governance. London: The Society; 1999.

- Department of Health, Pharmacy in the future, implementing the NHS plan. London: The Department; 2000.

- Department of Health. Clinical governance in community pharmacy: guidelines for good practice for the NHS. London: The Department; 2001.

- Department of Health. Building a safer NHS for patients — implementing an organisation with a memory. London: The Department; 2001.

- NHS Primary Care Contracting. Community pharmacy assurance framework. Available at: www.primarycarecontracting.nhs.uk/114.php (accessed 18 August 2006).

- Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. Pharmacy contract. Available at: www.psnc.org.uk/index.php (accessed 19 July 2006).

- Elvey R, Bradley F, Ashcroft DM, Noyce P. Commissioning services and the new community pharmacy contract: (1) Pharmaceutical needs assessments and uptake of new pharmacy contracts. Pharmaceutical Journal 2006;277:161–3.

- Bradley F, Elvey R, Ashcroft DM, Noyce P. Commissioning services and the new community pharmacy contract: (2) Drivers, barriers and approaches to commissioning. Pharmaceutical Journal 2006;277:189–92.

- Elvey R, Ashcroft DM, Bradley F, Hassell K, Kendal J, Noyce P, Sibbald B. Setting up local pharmaceutical services — lessons for primary care trusts. Pharmaceutical Journal 2005;274:546–8.

- Campbell SM, Sheaff R, Sibbald B, Marshall MN, Pickard S, Gask L, et al. Implementing clinical governance in English primary care groups/trusts: reconciling quality improvement and quality assurance. Quality and Safety in Health Care 2002;11;9–14

- Commissioning services and the new community pharmacy contract: (3) Uptake of enhanced services. Pharmaceutical Journal 2006;277;224–6.