Abstract

Aim

To adapt and validate the general level competency framework to be relevant for primary care and community pharmacists. To compare the framework with the Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s “Competencies of the future pharmacy workforce” document.

Design

Literature review, consensus development panels, expert panel, mapping.

Subjects and setting

Members of the consensus development panels were representatives from primary care trusts, multiple pharmacy organisations, key stakeholder organisations and individual community pharmacists.

Results

The literature review identified 78 behavioural statements, reduced to 69 statements by the expert panel review. These 69 statements were mapped onto a framework previously developed for secondary care. Amendments and additions were made and agreed by the consensus development panels. The adapted framework consisted of 104 behavioural statements organised into four clusters: delivery of patient care, personal, problem solving and management and organisation. When this framework was mapped against the 266 statements listed in the Society’s report, 218 could be located in the adapted framework.

Conclusions

This study has adapted the general level framework for pharmacists working in primary care and community pharmacy. The framework is evidence-based, grounded in the literature and validated by expert and individual pharmacist opinion. A controlled trial to test the effectiveness of the adapted general level framework as an educational intervention to improve the competence of primary care and community pharmacists is currently under way. The framework complements the Society’s initiative and has the potential to turn the “Competencies of the future pharmacy workforce” into a format that could usefully be adopted as a performance enhancement tool.

Recent reports and subsequent policy have emphasised the need for health care professionals to have relevant and up-to-date skills and expertise. In particular, the Kennedy Report in 2001 emphasised the need for regulation aimed at maintaining the competence of professionals and the importance of periodic performance appraisals, coupled with continuing professional development (CPD).1 These drivers, along with an increasingly well informed and sceptical public, make clear the need for a strategy that will develop practitioners who are fit for purpose.

In January 2005, CPD became a professional requirement for all practising pharmacists. CPD is expected to become mandatory by the end of 2005 so that pharmacists will be required to submit their CPD records to the Royal Pharmaceutical Society for review every three to five years in order to maintain their practising rights. A CPD record can demonstrate how learning from mistakes, appraisal, peer review, critical incidents, audit and other key activities feeds into the pharmacist’s learning. However, one of the major barriers to the successful implementation of CPD is the lack of a system to help pharmacists identify their learning needs, since many in primary care and community pharmacy work in isolation and are not subject to regular performance appraisal. Success in needs assessment is dependent on knowledge of the competencies required to undertake a job effectively. In addition, CPD is not a measure of competence, in that participation in the CPD process does not ensure that a person is able to carry out the tasks expected of them in their role.

Competence can be defined as ability based on work or job outputs.2 A competency is an underlying characteristic of an individual that is causally related to effective performance3 and behavioural statements describe the behaviours that would be observed when someone demonstrates competency. A competency framework is a complete collection of the competencies that are thought to be needed for effective performance: closely related behavioural statements are organised into competencies and related competencies are grouped together in clusters. A successful competency framework must be usable and fit for its purpose, should include indications of performance outcome and it must conform to the following quality standards:2

- Involve the people who will be affected by the framework

- Be clear and easy to understand

- Be relevant to all staff who will be affected by the framework

- Take account of expected changes, eg, in the organisation’s environment, new technology, future work practices

- Have discrete elements, ie, behavioural statements do not overlap

- Be fair to all affected by its use

The pharmacy profession has grasped the competency issue with great enthusiasm and to such an extent that currently there are available a number of different approaches to competency specification. A recent addition is an initiative from the Society’s policy development unit defining the competencies of the future pharmacy workforce.4,5 Competencies were identified from a review of over 70 government policy documents, pharmacy degree accreditation criteria and the preregistration training performance standards and registration examination criteria. While this work provides extensive descriptor terms, the Society recognises that this work is not yet in a format that can usefully be used for testing performance or as a performance-enhancing tool and that further work is needed to put the competencies into operation.5 In addition, the list has been “reality tested” on pharmacists working in new or evolving roles, which may not be representative of the general population of GB-registered pharmacists.

This testing has split the competencies into core competencies required by all pharmacists and additional sector specific competencies (community, hospital and primary care). The competencies required by, for example, community pharmacists include “emergency supply” and “supply/sale of over-the-counter medicines”. However these are job descriptions for community pharmacists. Competencies, per se, are the underlying characteristics of the individual that allow them to be able to complete these job tasks effectively. Therefore, to make an emergency supply, or an OTC sale, a community pharmacist must use appropriate questioning, apply legal and ethical requirements and make a decision based on the information gathered. These behavioural competencies are needed for the job tasks of all sectors of the profession. A unified competency framework could, therefore, address the needs of all sectors of the profession. Indeed, there is a danger that a lack of a uniform approach will fail to provide a clear and logical career pathway for pharmacy practitioners.

A new contractual framework for community pharmacists has been introduced to be effective from April 2005. The new contract will allow community pharmacist to develop patient centred medicines management services, and will take the focus away from dispensing prescriptions. In order to provide advanced services under the new contract, pharmacists must become accredited by undertaking a competency-based assessment through a higher education institution. This is to assure the quality of the service by ensuring the competence of the pharmacists providing the service.

The competency framework for the assessment of pharmacists providing medicines use review (MUR) and prescription intervention services was published in January 2005.6 The framework does not contain all the competencies that might be required to provide MUR, but those that can be assessed in a robust and reliable manner. Pharmacists do not have to undertake training in preparation for the assessment, but many may choose to do so. In order to provide a high quality service, pharmacists will need to be able to identify and address their learning needs in all the areas of competency required for MUR.

The need for a competency framework that will help develop pharmacists who are fit for purpose is clear. A competency framework that describes the skills, knowledge, attitudes and behaviours for pharmacists, rather than the job outputs, can be applied to all sectors of the profession and to all job outputs including MUR. A hybrid competency framework that allows performance to be rated and compared against a standard can be used as a performance enhancement tool by helping pharmacists identify their learning needs for CPD. To be successful this framework must comply with the quality standards described earlier and it could form part of an overall pharmacist development strategy.

Research by our group in secondary care has led to the design and evaluation of a competency framework for facilitating the development of pharmacists at a general level of practice (the general level framework).7,8 The performance of the individual is assessed using a rating scale, which provides a significant formative stimulus. In a controlled study, use of the general level framework produced an improvement in individual performance that was sustained over a 12-month period. The benefits were related directly to the framework’s explicit and structured description of the required competencies, and the assessment ratings allowed the pharmacist to compare their performance against a prespecified standard.

This general level framework is one element of an overall strategy for pharmacist development from a newly registered pharmacist to, potentially, a consultant.9 An evidence-based approach to the development of pharmacy practitioners who are fit for purpose would make use of the existing, validated general level framework and to develop it to capture the activities undertaken in other areas of the profession, rather than designing a new framework for each discipline. This will allow one framework to address the broader needs of the profession.

This paper describes the adaptation the general level framework7 to support primary care and community pharmacists. The research was undertaken at the same time as the Society’s initiative on the competencies of the future pharmacy workforce,4 hence the latter could not be included in the initial adaptation of this competency framework. However, the aim of the research was to produce an evidence-based framework and hence take account of work such as that of the Society’s policy development unit’s. In addition, the research described here complements the Society’s work and could be used to put their competencies into operation. Therefore, this paper goes on to compare the competency framework with the “Competencies of the future pharmacy workforce”.4

Methods

The methods used to adapt, validate and compare the general level framework are summarised below.

Adaptation and validation of the framework

A literature review of NHS policy, professional body strategy and research documents relating to the current and future roles of primary care and community pharmacists was undertaken. Medline was searched using the search terms “competence”, “competency”, “community pharmacy”, “primary care pharmacy”, and “role”. In addition the internet sites of the Department of Health, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society and the National Prescribing Centre were searched for relevant strategic and policy documents, and the internet and manual searching identified current competency frameworks for pharmacists. These documents were analysed to identify a list of behavioural statements that could describe the competencies expected of primary care and community pharmacists.

The next stage convened an expert panel of pharmacists, with expertise in community practice, primary care pharmacy and research and education, who reviewed this list of behavioural statements to identify any overlap and omissions.

The behavioural statements corroborated by this expert panel were then incorporated into the existing general level framework.7 Amendments and additions to the framework were made and a draft framework produced that included the behaviours identified for pharmacists working in primary care and community pharmacy.

This draft framework was reviewed by three consensus development panels to ensure its relevance for pharmacists working in primary care and community pharmacy. Panel members comprised representatives from key stakeholder organisations, primary care trusts, local pharmaceutical committees, multiple pharmacy organisations and individual community pharmacists.

Each panel was facilitated by a pharmacist with expertise in primary care and community pharmacy, and with knowledge of the framework. Panel members were asked to reach consensus on the relevance of each behavioural statement for general level primary care and community pharmacists, or recommend amendments and inclusions to the framework if necessary.

The expert panel reviewed the findings of the consensus panels. Each revised competency cluster was reviewed in order to ensure consistency of terminology, overall content, and compatibility with the general level framework for secondary care, and the framework was reviewed as a whole to ensure it met the quality standards described earlier.2 The framework was sent to the consensus development panel members and the National Prescribing Centre for a final consultation.

Comparison with “Competencies of the future pharmacy workforce”

The competency framework produced was compared with the Society’s “Competencies of the future pharmacy workforce”4 with particular focus on the design, usability and content of the documents.

This comparison also aimed to ensure the adapted general level framework encompassed the relevant competencies from the Society’s work.

Results

Adaptation and validation of the framework

The literature review identified 15 policy and strategy documents published by the NHS and pharmacy organisations and 19 other relevant articles relating to the role of community and primary care pharmacists. In addition, nine research documents were found on the Society’s website that related to the expanding role of community pharmacists. Four existing competency frameworks were used in the review:

- National Prescribing Centre/NHS Executive. Competencies for pharmacists working in primary care (2000).

- London, Eastern and South East Specialist Pharmacy Services. Clinical Pharmacy: a competency framework for pharmacy practitioners, general level (2003).

- London, Eastern and South East Specialist Pharmacy Services. Clinical Pharmacy: a competency framework for pharmacy practitioners, advanced level (2003).

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society. CPD plan and record. Appendix 4: Key areas of competence.

In total 78 behavioural statements were identified from the literature review and content analysis of the four frameworks. These 78 statements were reviewed by the expert panel for overlap and the final list used to adapt the existing general level framework contained 69 behavioural statements.

The development and content of the framework for pharmacists in secondary care has been described previously.7 It contains three competency clusters: delivery of patient care, personal competencies and problem solving competencies. The mapping of the behavioural statements from the literature review and expert panel confirmed the importance of these three existing competency clusters, although some amendments were necessary to include additional behaviours (Panel 1) and to ensure the language used was universal for all areas of the profession. The most significant amendment to the general level framework was the addition of a fourth cluster to describe the management roles of community and primary care pharmacists: the management and organisation cluster. This draft of the framework was reviewed by the consensus development panels.

The panels agreed changes to some competency titles, behaviour headings and descriptors for clarification purposes and that the order of the competencies within the patient care cluster needed to be revised the better to reflect a consultation approach to patient care. Amendments to the framework included:

- Addition of behaviours around patient consent and knowledge of the legislation affecting patient care in the patient care cluster

- Addition of an overarching statement relating to professional accountability in the personal cluster

- Addition of behaviours relating to problem identification and understanding the mechanisms of drug-drug interactions in the problem solving cluster

- Addition of behaviours relating to ensuring a safe working environment, risk management and mentoring to the management and organisation cluster

The expert panel agreed to the majority of amendments and additions proposed by the consensus development panels and was happy that the adapted framework maintained its applicability to those pharmacists working in secondary care. No further amendments were made as a result of the final consultation. The final competency framework consisted of 104 behavioural statements, organised into four clusters. A concise overview of the framework is given in Panel 2. For the purpose of this paper the final framework will be referred to as the adapted framework.

Comparison with “Competencies of the future pharmacy workforce”

Two hundred and eighteen of the 266 Royal Pharmaceutical Society competencies were located in the adapted framework. Of those not found, 14 competencies were considered to represent advanced practice. The remaining 34 competencies were too broad or ambiguous to be able to map to the adapted framework, with five of these associated with working in different settings. The Society’s competencies mapped onto all but one in the adapted framework. This behaviour was “inspires confidence”.

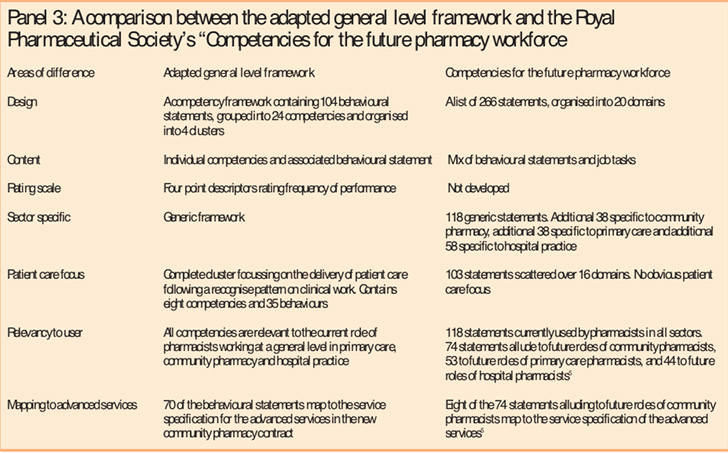

Panel 3 provides a brief comparison between the Society’s competencies and the adapted framework. The documents differ in design: while the adapted framework is a typical competency framework2 as described earlier, the Society’s initiative is a list of competencies and tasks organised into domains. Table 1 summarises the mapping of the competencies to the adapted framework and clearly illustrates that a degree of congruence exists.

Discussion

We have modified the general level framework originally designed for pharmacists working in secondary care to support pharmacists working in primary care and community pharmacy. The adapted framework was produced following an established approach and is evidence-led, grounded in the literature and validated by expert and individual pharmacist opinion. No member of the consensus development panels expressed concerns about the approach adopted, or that the overall aims of the research were inappropriate. The support and enthusiasm for the research demonstrated by the members of the consensus development panels confirmed the need for a competency framework such as this.

The behavioural statements identified from the literature review mapped onto the original general level framework with few amendments. This validates the original general level framework and ensures that the adapted framework maintains applicability for secondary care.

The main addition to the framework was the introduction of the management and organisation cluster, which the expert panel deemed to be relevant for secondary care as well as primary care and community pharmacy.

The general level framework in its original form has been tested in secondary care and is shown to be effective in improving the competence of general level pharmacists.8 It has now been implemented in approximately 70 hospital trusts. A controlled trial to test the effectiveness of the adapted framework as an educational intervention to improve the competence of primary care and community pharmacists is currently under way. The framework is being tested in community pharmacists, locum pharmacists and pharmacists working on a sessional basis providing medication reviews for PCTs or GP surgeries. These pharmacists are using the framework to identify their learning needs for CPD. The results of this trial, due at the end of 2005, will demonstrate whether the adapted framework is effective at developing the competence of pharmacists in primary care and community pharmacy.

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s competencies and the adapted framework were developed with a different focus and used different approaches to the work. Nevertheless there is considerable congruence between the documents. This is supported by the fact that 218 of the 266 Society competencies were located in the adapted framework, and that these 218 competencies mapped onto all but one of the competencies in the adapted framework.

Although it seems from the comparison that there are areas in the Society competencies that are not covered in the adapted framework, these are explained by a number of the Society’s competencies being more applicable to advanced practice or future roles. Fourteen of the Society’s competencies that do not map to the adapted framework are advanced level competencies and are embraced in the advanced level framework10 developed by our group.

Work by the Society has identified 74 competencies from its document that are currently not used by community pharmacists and 53 that are not used in primary care (Panel 3). These have been identified through judgement on the Society’s part about the future roles of community and primary care pharmacists.5 Interestingly, when these competencies were compared with the activities required of community pharmacists providing advanced services under the new contract, a gap still remains: only eight of these competencies map to the service specification for advanced services (Panel 3).

The adapted framework better reflects the current status of pharmacy practice and that intended under the new pharmacy contract (Panel 3).

The content of the adapted framework has been further recognised by the influence it has had on the development of the competency framework for assessment of pharmacists providing the MUR and prescription intervention services under the new contractual framework.6

The Society’s initiative was not designed to create a tool by which performance could be measured, although this is a future application of the work. The comparison indicates how the adapted framework complements the Society’s initiative and could be used to develop the Society’s document into a useful tool for performance enhancement. The adapted framework encompasses 218 of the Society’s competencies and is usable and of a manageable size (104 statements compared with 266, Panel 3). It contains four distinct clusters focusing on the competencies needed to be an effective pharmacist. These competencies are found throughout the Society’s list in many different domains, making the document difficult to navigate (Table 1). The adapted framework contains a four-point rating scale enabling performance to be assessed for each behaviour. This design has been shown to be effective as a performance enhancement tool in secondary care,8 and is currently being tested as a tool to identify learning needs in primary care and community pharmacy.

Conclusion

This comparison highlights the high degree of congruence between the two frameworks and suggests that the adapted framework provides a useful springboard to put the Society’s “Competencies for the future pharmacy workforce” into operation. The adapted framework is part of an overall strategy for pharmacist development that will provide a competency package to progress pharmacists from general level through to advanced level and potentially to consultant pharmacist level.9 The evaluation of the adapted framework will provide evidence for the first step of this strategy in primary care.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to North West London Workforce Development Confederation and Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire Workforce Development Directorate for providing funding for this project. We thank all the members of the consensus development panels and those who have reviewed the framework for their time and input. For their support in the evaluation of the framework currently under way, our thanks to: London Pharmacy Education and Training; Essex, Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire, Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire LPCs; the PCT pharmacists in those areas who have helped with recruitment; Sue Smith from Lloyds pharmacy, Tony Cook from Moss Pharmacy and Simon Swallow from Boots Pharmacy; the facilitators for the project; and all the pharmacists taking part in the evaluation. Finally, we acknowledge the continuing efforts of the other members of the Competency Development and Evaluation Group in relation to both the general and advanced level frameworks.

This paper was accepted for publication on 3 June 2005.

About the authors

Elizabeth Mills, BPharm, MRPharmS, is primary care competency project manager, at the School of Pharmacy, University of London. Denise Farmer, BPharm, MRPharmS, is associate director of clinical pharmacy, Eastern. Ian Bates, MSc, MRPharmS, is professor and head of educational development at the School of Pharmacy, University of London. Graham Davies, PhD, MRPharmS, is academic director of clinical studies, School of Pharmacy and Biomolecular Sciences, University of Brighton, and associate director of clinical pharmacy, South East. David Webb, MSc, MRPharmS, is director of clinical pharmacy, London, Eastern and South East Specialist Pharmacy Services. Duncan McRobbie, MSc, MRPharmS, is principal clinical pharmacist, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London.

Correspondence to: Elizabeth Mills, Department of Practice and Policy, School of Pharmacy, University of London, 29–39 Brunswick Square, London WC1N 1AX (e-mail elizabeth.mills@ams1.ulsop.ac.uk)

References

- Department of Health. The report of the public inquiry into children’s heart surgery at the Bristol Royal Infirmary 1984–95. Learning from Bristol. CM 5207(1). London: Department of Health; 2001.

- Whiddett S, Hollyforde S. The competencies handbook. London: Institute of Personnel and Development; 1999.

- Spencer LM, Spencer SM. Competence at work: models for superior performance. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 1993.

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Competencies of the future pharmacy workforce. London: The Society; 2003.

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Competencies for the future pharmacy workforce: Phase 2 report. Reality testing of a draft framework of knowledge, skills, attitudes and behaviour required for future pharmacy roles. London: The Society; 2004.

- Department of Health. The new contractual framework for community pharmacy. London: The Department; 2004.

- McRobbie D, Webb DG, Bates I, Wright J, Davies JG. Assessment of clinical competence: designing a competence grid for junior pharmacists. Pharmacy Education 2001;1:67–76.

- Antoniou S, Webb DG, Davies JG, Bates IP, McRobbie D, Wright J, et al. General level competency framework improves the clinical practice of hospital pharmacists: final results of the south of England trial. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2004;12(Suppl):R22–23.

- Davies JG, Webb DG, McRobbie D, Bates I. Consultant practice — adopting a strategy for practitioner development. Hospital Pharmacist 2004;11:2.

- Meadows N, Webb DG, McRobbie D, Antoniou S, Bates I, Davies GD. Developing and validating a competency framework for advanced pharmacy practice. Pharmaceutical Journal 2004;273:789–92.