Medicines information (MI) has been a well established service in the UK since 1969, handling over half a million queries each year. There is evidence from regular, national user-satisfaction surveys that the MI service is appreciated by enquirers, but little published work exists evaluating the direct impact of UK NHS MI enquiry answering services on patient care.

A systematic review of the clinical and economic impact of MI services on patient outcome included six papers from the UK, the US and Canada.[1]

Five of the studies used questionnaires or interviewed enquirers retrospectively, while one was prospective in design. Enquirers’ accounts of events were the main source of information about outcomes. One study corroborated this subjective description by referring to medical records and another evaluated the effect on patient outcome independently by involving an expert panel. All of them attempted to evaluate the impact of MI on patient care, but few used a rating scale. Most used questionnaires asking if the information was useful or had a positive impact, but without commenting on the seriousness or significance of that impact. Each study reported favourable results, but the authors concluded that the impact of MI consultation on patient care had not been investigated rigorously enough to provide conclusive evidence of direct patient benefit.[1]

The aims of the study were:

- To measure the proportion of queries from healthcare professionals where information or advice provided by MI is used by enquirers in the management of patients

- To identify the actions taken by healthcare professionals as a result of the information or advice provided

- To assess whether the information or advice has a direct impact on outcome

- To measure the proportion of queries from healthcare professionals where the enquirer is waiting for an answer from MI before he or she can proceed with the care of the patient

- To propose a minimum expected level of uptake of MI enquiry answers by health-care professionals

Method

Data were collected prospectively in two MI centres at a teaching hospital over a period of two weeks. Requests for information from healthcare professionals regarding patient-specific issues were included, with the exception of those from NHS Direct. At the time enquiries were initially taken callers were asked:

- If they were waiting for an answer before proceeding with treatment

- Where they would go for an answer to their enquiry if the MI service did not exist

- What they expected the patient outcome to be at this stage

Enquirers were contacted between seven and 28 days later; semi-structured interviews were conducted to determine what patient outcome resulted and to ascertain whether they used the information provided and, if so, how it was implemented. Information used in this context refers to the enquiry answer which could consist of information, a recommendation or advice offered by MI staff.

The study was a service evaluation and did not require research ethics committee review.

Results

During the recruitment period, 40 enquiries met the inclusion criteria: 17 (43 per cent) from pharmacists, 16 (40 per cent) from doctors, six (15 per cent) from nurses and one (3 per cent) from a dentist.

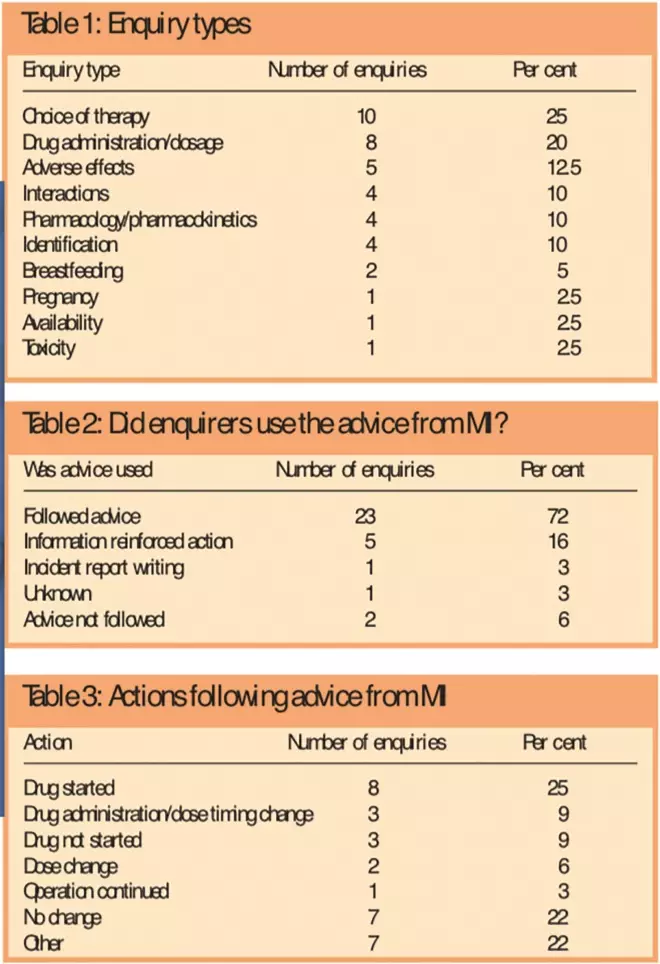

The most common enquiries were for information about choice of therapy (10, 25 per cent) followed by drug administration or dosage (8, 20 per cent) and adverse effects. (5, 12.5 per cent) (see Table 1).

Tables 1, 2 and 3: Enquiry types; Did enquirers use the advice from MI?; and Actions following advice from MI

A high proportion (32, 80 per cent) of enquirers were waiting for an answer from MI before continuing, five (12.5 per cent) were managing their patients’ problems but needed confirmation of their action plans or help to optimise treatment, one enquirer was uncertain, and one enquirer’s patient had died so the information was only needed for reflection. The remaining enquirer requested the information to write an incident report.

Alternative sources enquirers might use if the MI service was not available yielded 48 responses: 12 (25 per cent) stated they would look on the internet (no sites specified), 10 (21 per cent) would approach another member of the pharmacy team such as a ward pharmacist, or one in the dispensary, nine (19 per cent) would ask another professional colleague (not pharmacy), nine (19 per cent) would look in books (none specified), seven (15 per cent) would use other MI sources (either use the references in the MI office or call a different MI centre), five (10 per cent) would contact the drug manufacturer and five (10 per cent) mentioned other resources. Of these, two respondents did not know where else to look.

At the time enquiries were submitted, it was ascertained that 14 enquirers (55 per cent) predicted the patient would improve, 11 (38 per cent) aimed to maintain the patient’s state of health, four (12.5 per cent) claimed prognosis was unknown at this stage and two (5 per cent) thought the patient would deteriorate. One patient had died.

A total of 32 (80 per cent) follow-up telephone surveys were completed. Sixteen enquirers (40 per cent) were available on first contact, seven (17.5 per cent) on second contact and nine (22.5 per cent) on third or fourth contact. Eight (20 per cent) were unavailable after four attempts and were considered lost to follow-up. Three of these were followed up by e-mail at their request.

Patient outcome descriptions were reported at the follow-up. Respondents indicated that 19 patients (59 per cent of outcomes) matched the expected outcome, three (9 per cent) had improved when it was expected that they would remain the same or deteriorate or the expected outcome was unknown and six (19 per cent) remained the same when they had been expected to improve. Four outcomes (13 per cent) were unknown. Therefore, for all the known outcomes the patient’s health remained the same or had improved.

Enquirers used the information or advice provided by MI in 30 out of the 32 enquiries (94 per cent) followed up (Table 2). Recommendations from MI prompted various actions by the enquirers in the management of their patients. Most commonly, MI advice led to therapy initiation (Table 3). There were two enquirers (6 per cent) who did not use the information provided and the reasons given for their decisions were that MI was unable to provide additional information and information was for future reference.

Discussion

Our results suggest that in the opinion of healthcare professionals, MI does have an impact on patient care, and the vast majority of the enquirers used the information provided. Although the internet has rapidly developed as a source of information, MI pharmacists continue to play a key role in providing objective, evidence-based advice, which is accepted and acted upon by healthcare professionals to optimise care.

Details of patient outcomes here were limited to enquirers’ opinion of short-term patient response, with no independent confirmation of the patient’s clinical picture. Future studies could employ an independent panel to reduce bias.[2]

Although it was useful to learn the expected clinical outcome of patients at the onset of the MI enquiry and their progress two weeks later, the survey question did not prompt a detailed enough response to be able to verify that MI influenced the changes. Causality cannot be determined. However it was reassuring to note there was only a small proportion of patients whose health did not improve as expected.

This is in line with a previous literature re-view which found that MI services resulted in improved patient outcome.[2]

A German study of user satisfaction and potential positive patient outcomes from their national drug information service identified positive patient outcomes in 42 per cent of cases.[3]

Themes identified in this work on patients’ clinical progress and the actions taken by enquirers will be helpful in future work to develop questionnaires and rating scales to assess MI’s impact on patient care. Details of how the recommendations from MI were applied in practice, and the reasons for advice not being followed, could be used to evaluate the quality of the service provided.

Other studies have found that 76–94 per cent of enquirers followed advice given by MI, which corroborates the results found here.[4],[5]

Before this study, uptake of advice from MI was not routinely measured. On the basis of this, the MI services at the participating departments have now set a preliminary standard for 90 per cent of patient-specific enquiry answers to be accepted by health-care professionals and used for patient management. Specific questions from this project have been incorporated into the MI user satisfaction survey to ascertain if collation of this type of data is feasible on a larger scale.

Conclusion

In conclusion, most MI answers to patient-specific queries are needed by healthcare professionals before further therapeutic decision making. In the opinions of MI service users the advice from MI has a favourable impact on patient care in a large proportion of cases. Further study is needed to detect the significance of this effect on patient care.

This paper was accepted for publication on 5 November 2008

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to pharmacy staff and enquirers in the MI departments at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, and to Alison Innes, principal MI pharmacist at Northwick Park Hospital.

Diane Bramley, MRPharmS, is senior pharmacist medicines information,

Champa Mohandas, MRPharmS, is a pharmacist, Satpal Soor, MRPharmS, is principal pharmacist, medicines information, David Erskine, MSc, MRPharmS, is director of the London and South East Medicines Information Service, and Alice Oborne, PhD, MRPharmS,is principal pharmacist, medicines use research at the department of pharmacy. All at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London

Correspondence to: Diane Bramley, Department of Pharmacy, St Thomas’ Hospital, Lambeth Palace Road, London

SE1 7EH (tel 020 7188 5018, e-mail Diane.Bramley@gstt.nhs.uk)

References

[1] Hands D, Stephens M, Brown D. A systematic review of the clinical and economic impact of drug information services on patient outcome. Pharmacy World and Science 2002;24:132–8.

[2] Spinewine A, Dean B. Measuring the impact of medicines information services on patient care: methodological considerations. Pharmacy World and Science 2002;24:177–81.

[3] Bertsche T, Hammerlein A, Schulz M. German national drug information service: user satisfaction and potential positive patient outcomes. Pharmacy World and Science 2007;29:167–72.

[4] Cardoni AA, Thompson TJ. Impact of drug information services on patient care. American Journal of Hospital Pharmacy 1978;35:1233–7.

[5] Golightly LK, Davis AG, Budwitz WJ, Gelman CJ, Rathmann KL, Sutherland EW, et al. Documenting the activity and effectiveness of a regional drug information center. American Journal of Hospital Pharmacy 1988;45:356–61.