Key points

- Pharmacists are integral members of the multidisciplinary team (MDT), bringing with them a unique clinical skillset as medicines experts;

- Pharmacist polypharmacy reviews are valuable to all patients, especially for those with complex healthcare needs. In this group of patients, GPs normally spend a large amounts of time with medicine-related issues that could be dealt with by a pharmacist;

- MDT cross-referral and social prescribing can reduce GP burden;

- Many of the older, frail patients who took part in the study took a large number of medicines, many of which are no longer indicated and/or causing adverse effects; therefore, deprescribing was a significant intervention;

- Polypharmacy reviews are cost-effective, not only owing to immediate interventions such as deprescribing and medicines optimisation, but also owing to the downstream effects these reviews can have, such as reduced falls and fracture risk following the deprescribing of anticholinergics and proton pump inhibitors.

Introduction

Polypharmacy can be appropriate and beneficial for a wide range of patients, but inappropriate polypharmacy can emerge owing to several reasons, including increasing age, frailty, multimorbidity, complex medication regimens, declining kidney and/or liver function, drug–drug interactions and drug–disease interactions[1]

.

In primary care, pharmacist contributions to the care of the most complex patients can be varied, which is often dependent on the perceived need for a holistic polypharmacy review.

Some patients in the community remain unidentified by data examined using the Scottish Patients at Risk of Readmission and Admission (SPARRA) risk prediction tool and, as a result, are often omitted from cases assigned for additional pharmacy review[2],[3]

.

Complex patients, with multimorbidity and polypharmacy, are regularly in contact with their GP and out-of-hours healthcare services owing to frequent, acute presentations. However, this means that there are few opportunities for a polypharmacy review while the patient is well, resulting in little or no input from pharmacy services.

There are more than 8.6 million unplanned hospital admissions in Europe each year owing to adverse drug reactions, up to 50% of which could have been avoided. Those who take five or more medicines and patients aged over 65 years are the most affected[1]

. Each disease has national and local guidelines outlining optimal management and best practice, but there is no distinct guide on how to treat multiple morbidities and complex medication regimens[4]

. There is evidence suggesting that patients living in deprived areas are more likely to become frail 10–15 years earlier than patients in less deprived areas, which poses a risk of inappropriate polypharmacy because these patients are more likely to take medicines from a younger age[1],[5]

.

With an increasing rate of frail and older patients with complex multimorbidities and poor engagement with healthcare services, socio-economically deprived communities display the classic characteristics depicting Julian Tudor Hart’s ‘inverse care law’, which suggests that those who most need medical care are least likely to receive it, while those with least need of healthcare tend to use health services more (and more effectively)[6]

.

Govan — a district of Glasgow — is one of the most socio-economically deprived areas in Scotland, with a diverse population of more than 29,000 people served by six GP practices[7]

. All GP practices in Govan are among the 100 ‘Deep End Practices’ serving the most deprived communities of Scotland[8]

. It is recognised that these practices lack the time, links to other services, and NHS support that is needed to prevent and reduce health inequalities[8]

.

The Govan Social and Healthcare Integration Partnership (SHIP) project, supported by the Scottish government’s ‘primary care transformation fund’, commenced in 2015 and aimed to develop new ways of working between general practice and social care services to provide seamless patient care. The project was conceptualised by teams from four GP practices in Govan, which then went on to pilot the project. The two remaining Govan GP practices were not involved owing to financial and logistics constraints.

The SHIP project was developed to promote shared working among the practice’s local primary care healthcare team — a multidisciplinary team (MDT) of healthcare and social work professionals. It was envisaged that greater horizontal and multi-agency referral would enhance continuity of care and provide both supportive and preventative measures. More regular and consistent referrals would, in turn, ensure that the most appropriate professional responded to patient needs at the most appropriate time[9]

.

When each patient was identified for inclusion within the project, the project team sought verbal consent and referred each participant to a patient information notice (see Supplementary file: ‘Appendix – The Govan SHIP Project’), which was available on each GP practice’s notice board. The notice contained essential information about the project, including who was involved as well as confidentiality information. Patients were invited to ask the practice manager or project manager for further information where required.

The SHIP project used a person-centred approach to identify patients based on individual needs and within the four GP practices participating in the project, any patient with complex healthcare considerations, regardless of age, were eligible for inclusion, including:

- Frailty;

- Vulnerability;

- Complex polypharmacy;

- Medication compliance issues.

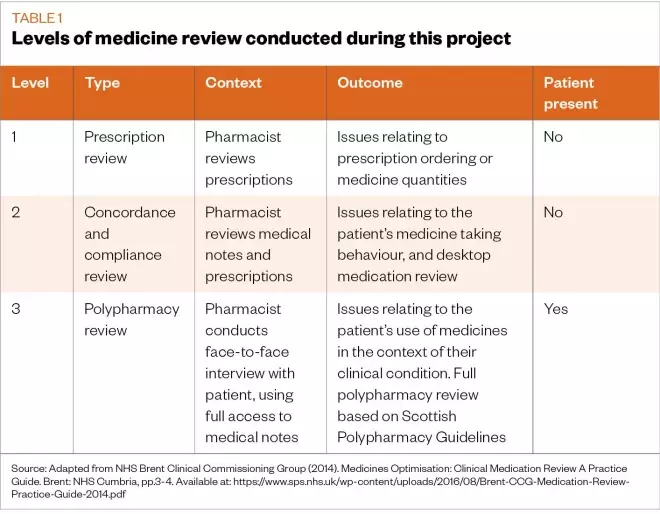

The SHIP project created opportunities to provide pharmaceutical care for patients with inappropriate polypharmacy who would otherwise have not received significant input, especially those who were housebound. The type of medication review can be described depending on the level of pharmacy input required (see Table 1). ‘Level 1’ and ‘level 2’ medicine reviews were non-patient facing and could be mostly desktop-based, with/without access to the patient’s full medication record, and could result in some technical amendments with little or no clinical involvement. ‘Level 3’ required a holistic medication review, with direct patient contact either in person or via telephone, with full access to the patient’s medical history.

Table 1: Levels of medication review conducted during this project

Methods

Pharmacist polypharmacy reviews

Patients were identified for review by individual need and vulnerability based on the judgement of the healthcare professional from the participating practices rather than by traditional search tools, such as SPARRA or the electronic frailty index[9]

. This was a novel approach used to test a new way of working, contrary to a similar study by Nightingale et al. where patients were identified by medicine burden[10]

.

The authors found that some patients in need of polypharmacy review were “missed” from traditional search tools as they may not fulfil the criteria (e.g. number of medicines, age or frailty).

An experienced pharmacist with a qualification in independent prescribing was introduced to work across the four SHIP surgeries (0.5 whole-time equivalent) to provide polypharmacy input for patients identified by the MDT. The MDT for each participating GP practice comprised existing healthcare professionals within the practice, such as GPs, nurses and district nurses. For the purposes of the SHIP project, the MDT was further extended with the addition of representatives from the children and family support team, social care team, a community links practitioner, a dedicated pharmacist and a physiotherapist.

Patient screening

The pharmacist involved in the project from January 2018 to August 2018, had access to the medical records of all participating patients and proactively screened each patient referred. As their presence became more established within the MDT, further direct referrals from other members of the MDT for patients who required specific pharmacy input were received.

The pharmacist screened each patient and carried out level 1 and level 2 medication reviews, depending on the information required (see Table 1). These were non-patient facing desktop reviews using available prescription information (level 1) and medical records (level 2)[11]

.

Factors considered during the desktop reviews were risk of falls, based on falls history and current medicine; complex medication regimens; medicine toxicity; frailty; evidence of poor medicines compliance; and having limited mobility with little contact with the practice.

From the level 1 and level 2 reviews, the pharmacist was able to outline the patients’ pharmaceutical needs, allowing prioritisation for patients who required further pharmacy input. All patients taking medicines were invited for a review. Although patients were treated equally, those with higher perceived risk of harm were contacted first, based on the pharmacist’s clinical judgement from the desktop review. All eligible patients (i.e. those who required further pharmacy input) were then contacted to arrange level 3 reviews, involving a dedicated face-to-face polypharmacy review, either at the GP practice or during home visits for housebound patients. If patients were unable to attend, the pharmacist would consider a telephone review if appropriate, based on the complexity of their medicine.

Tools and resources

Resources, such as the Scottish polypharmacy guidelines and local disease-specific guidelines, were used to ensure a holistic polypharmacy review was performed[7]

. Furthermore, the pharmacist focused the review based on what was important to the patient. Patients were asked to bring all their medicines to the appointment, including anything bought over the counter, herbal medicines and supplements.

Medicine packaging can change over time, so it is important to make sure that patients could identify the medicines they were taking, which formed a basis for assessing current and future requirement for the medicine. This also helped the pharmacist to assess compliance because they were able to calculate over/under-ordering based on the medicine’s most recent issue date compared to the number of tablets remaining. Inhaler technique was assessed in all patients with asthma and COPD.

To assess the current requirement of medicine versus risks, tools such as the screening tool of older people’s prescriptions (STOPP), screening tool to alert to right treatment (START) and the anticholinergic burden (ACB) calculator were used and, if appropriate, dose reduction and deprescribing was discussed with the patient[12],[13],[14]

. To identify unmet needs, tools such as QRISK and the fracture risk assessment tool (FRAX) were used where appropriate[15],[16]

. Once these assessments were carried out, the pharmacist could authorise changes to the medicines where required, refer the patient to colleagues within the MDT and/or refer onwards to the community pharmacy for access to services, such as the minor ailments service (MAS), ‘Pharmacy First’ scheme and smoking cessation service.

Referrals

The pharmacist discussed non-pharmacological options with patients, where appropriate, with referrals made to services such as physiotherapy, rehabilitation and the mental health team. Networks were formed with the social care team, community links practitioner, and children and families support workers, which ensured the option of social prescribing.

Relevant members of the MDT could be contacted directly on an ad hoc basis, as well as at monthly MDT meetings. Each practice held its own monthly MDT meeting comprising of the practice team and the SHIP pharmacist and physiotherapist. All patients referred to the SHIP project were discussed at these meetings and new referrals could be added.

Data recording

After an invitation for review, patient engagement was assessed by recording attendance rates at appointments. Then, after each review, intervention data were recorded on a spreadsheet created by a senior prescribing support pharmacist in South Glasgow. Once medication changes were confirmed and actioned on the patient medical records system, the pharmacist made an entry reflecting this on the spreadsheet. A follow-up via telephone, further appointment or home visit was arranged depending on the complexity of the intervention.

The SHIP pharmacist also contacted and liaised with community pharmacies with the aim of building better relationships. Informal feedback was sought from pharmacy teams.

Multidisciplinary team feedback form

At the end of the project in August 2018, members of the MDT who were involved with the care of the SHIP patients and had worked with the pharmacist were invited to provide anonymous, formal feedback on pharmacy involvement using an online survey. The link to the survey was emailed to each practice’s lead GP, practice nurse and prescribing support pharmacist. To receive feedback from the stakeholders, members of the MDT were invited to provide feedback based on their involvement with the SHIP project and patients. The following questions were asked:

- How did you find pharmacy input to the SHIP project? ‘Excellent’, ‘good’, ‘satisfactory’ or ‘not effective’?

- Was pharmacy input into MDT meetings useful? Yes or no?

- Would you like to give any other feedback?

Seven out of eight MDT members responded to the survey. To make the form quick and easy to use, only three questions were asked. These questions were asked to gain a basic level of insight into MDT feedback for pharmacist involvement and interventions. Although there was informal feedback offered by patients, this was not recorded.

Ethical considerations

Verbal consent from each patient was obtained during the consultation with the original healthcare professional who, using their clinical judgement, felt the patient was eligible for a MDT review. At this stage, the referring healthcare professional explained why the referral to the MDT was required and what details would be discussed. Printed notices in each SHIP surgery explained the nature of the project and the inclusion of an anonymous service evaluation (see Supplementary file). All participants were able to opt out of the project at any point if they wished and each practice consented to anonymised data collection for purposes of service evaluation. The local Research Ethics Committee stated that formal clearance was not required as the study was an evaluation of a service.

Results

Patients

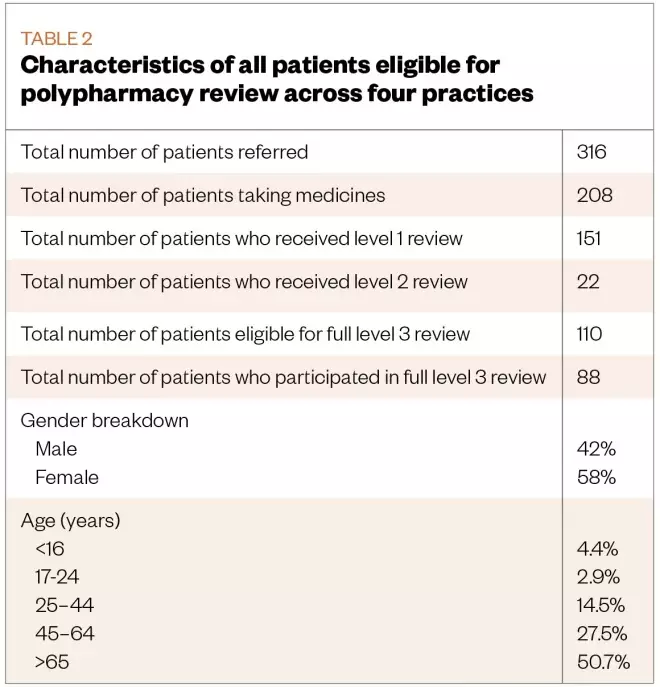

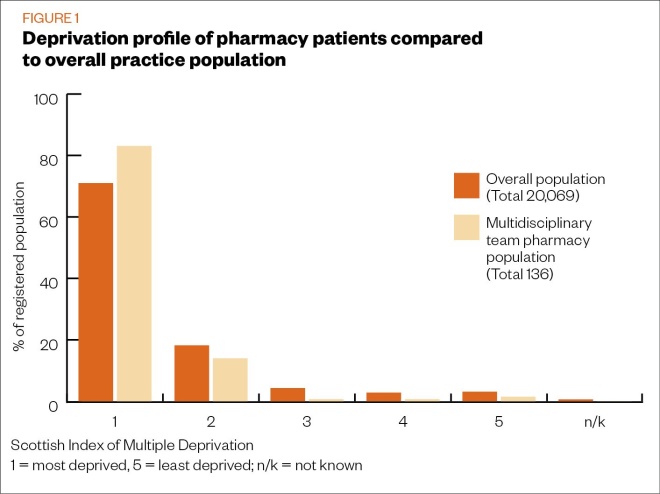

Table 2 shows characteristics of all patients screened. A total of 110 patients were eligible for polypharmacy review (see Table 2). It was found that 66% (n=209) were on between 1 and 24 repeat medicines (median 9.2). Patients with no medicines were screened for unmet needs and 82% (n=259) of all referred SHIP patients were from the most deprived quintile of socio-economic status (see Figure 1), as defined by the 2016 Scottish Index for Multiple Deprivation (SIMD)[17]

. Of the 88 patients who participated in a full level 3 review, 73% [n=64]) were female and 63% (n=55) were aged over 65 years old.

Table 2: Characteristics of all patients eligible for polypharmacy review

Figure 1: Deprivation profile of pharmacy patients compared to overall practice population

Following screening, 151 patients underwent level 1 with 22 patients undergoing level 2 review, with each of these considered for a level 3 face-to-face polypharmacy medication review. A large proportion of patients were housebound, therefore, 22% (n=33) of all reviews (n=151) were home visits. Patients unable to attend a face-to-face review were provided with a telephone consultation (23% [n=35] of the 151 patients) if the pharmacist deemed it appropriate, based on the complexity of their medicines.

Interventions

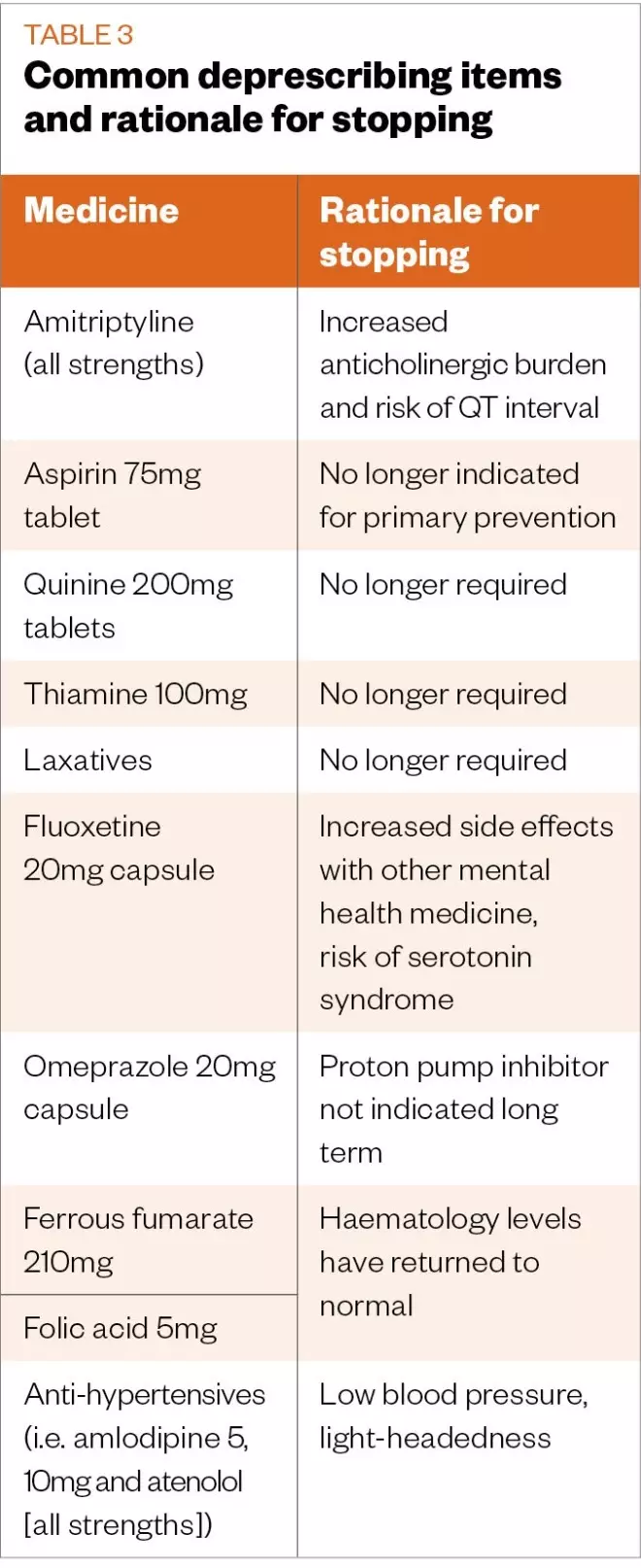

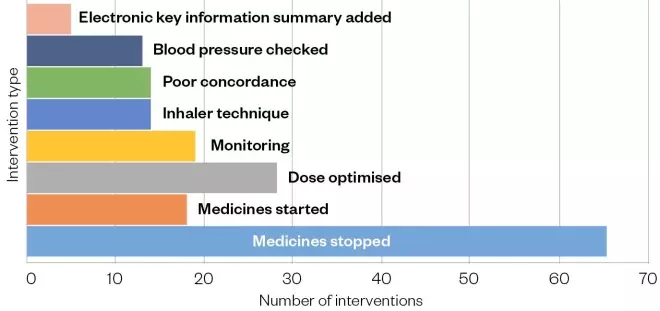

Following the reviews, a total of 65 medicines were stopped, 28 doses were optimised or reduced, and 18 new medicines were started (see Figure 2). There were several reasons as to why medicines were no longer required and considered for discontinuation. The most common deprescribing interventions were for patients where there was evidence of side effects and harm, such as increased risk of falls and toxicity (see Table 2). Overdue monitoring was identified in 17% of patients (n=19) and appropriate tests requested.

Table 3: Common deprescribing items and rationale for stopping

Figure 2: Summary of interventions resulting from pharmacist review (n=88)

The electronic Key Information Summary (eKIS) is an important source of information relay from primary to secondary care in the event of an unplanned admission or contact with unscheduled care services. When essential information relevant to anticipatory care (e.g. complex medication regimens) or social care arrangements (e.g. power of attorney) was found as a result of the face-to-face meeting with the patient it was added to eKIS by the pharmacist. The pharmacist updated eKIS information for five patients.

The pharmacist judged concordance to be poor in up to 13% of patients (n=14). Proactive blood pressure (BP) checking was undertaken in 12% of patients (n=13) and revealed that two patients had untreated hypertension; these patients were later started on appropriate medicine. Inhaler technique was checked in all patients with prescribed inhalers and the reviews revealed that 69% of all patients (n=15) with inhalers displayed inappropriate technique.

Non-pharmacological options were also considered — the pharmacist referred 29% of patients (n=37) to non-GP members of the MDT. Dependent on need, some patients required multiple referrals (i.e. social work and referral to the rehabilitation team). Of all 37 referrals made by the pharmacist, 40% (n=15) were for community pharmacy to ensure patients were utilising all available pharmacy services, such as the MAS and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), or for the dispensing of medicine compliance aids (MCAs). Community links practitioners provided a good source of social prescribing and 21% of patients (n=8) were deemed suitable to access community links practitioner services. Referral was made for the district nurse for 21% of patients (n=8) because they are regularly in contact with housebound patients. The social work team was contacted for 11% of patients (n=4).

Multidisciplinary team survey

Pharmacy input into shared patient care was rated as excellent by 71% and good by 29% of all respondents (n=7). Pharmacy input into the MDT meeting was rated as ‘useful’ by 100% of respondents. An open question was asked for “any other feedback” and the feedback was perceived by the author as being positive. Example responses included:

“Excellent relationship with the pharmacist benefiting the patients and the practice in equal measure.”

“Pharmacy input was extremely helpful and became a valued member of our SHIP meetings.”

Changes to referrals

Reviews were generally carried out in response to screening from the pharmacist during the early stages of the project. This was potentially due to the MDT not being accustomed to having a pharmacist as part of the team. As pharmacist presence became more established within the MDT, there was an increased number of direct referrals made from different members of the MDT. This helped identify patients requiring pharmaceutical review that otherwise may have been missed via traditional search tools, such as SPARRA.

Discussion

Deprescribing

It is estimated that up to 5% of all hospital admissions are medicine-related and up to 50% of these are owing to adverse drug reactions that could have been prevented[18]

. People aged over 65 years and taking five or more medicines are at highest risk of medicine-related hospital admission[19]

. Level 3 polypharmacy reviews (n=88) were performed within the SHIP project, with 63% (n=55) undertaken with patients aged over 65 years taking an average of eight medicines each.

A working definition of deprescribing has been proposed by Reeve et al, describing it as a “process of withdrawal of inappropriate medication supervised by a healthcare professional with the goal of managing polypharmacy and improving outcomes”[20]

. During the review, each item was discussed with the patient and medicines that were no longer indicated or required were considered for discontinuation.

Deprescribing should not be undertaken without careful consideration; therefore, the benefits and risks of each medicine were discussed with the patient considering up-to-date guidelines[21]

. Owing to the importance of patient input, side effects as well as positive and negative experiences were discussed in each review. Tools such as the ACB calculator and STOPP/START were utilised to identify risks, and numbers needed to treat was used as a tool to help demonstrate the effectiveness of the drug[1],[13],[14]

.

If they agreed to stop a medicine during a review, patients were reassured that it would be done in a controlled and step-wise approach, with follow-up as appropriate. Patients were generally open and agreeable to recommendations for stopping certain medicines, especially as it meant a reduced tablet burden, reflecting similar findings from recent research[22]

. Deprescribing was found to be one of the most common interventions made during the polypharmacy reviews, with a total of 65 items being stopped. The medicines deprescribed ranged from the relatively straightforward, ineffective medicine that was no longer needed or caused side effects, to more complex cases where secondary care were contacted if required (see Table 3).

Concordance

Compliance and adherence are important patient factors to ensure optimal therapeutic response. It is now recognised that patient–healthcare professional relationships are an important factor in ensuring concordance, thereby improving compliance and adherence[23],[24]

. In developed countries, only 50% of patients with chronic illness follow their treatment as prescribed[25]

. It has been previously demonstrated that patients with little or no knowledge of how their medicines work are more likely to miss doses. To improve patient compliance, patients need to be treated like a partner in their own care[25]

.

The SHIP project was developed to provide an opportunity for patients to gain better understanding of their medicines and ask questions about possible side effects and concerns that they had not previously mentioned to their GP. With more information about their medicines and being treated as a partner in their care, patients felt more empowered to take control of their own medicines and therefore, to be concordant with medicine regimens. Owing to project timescales, a review and follow-up of medicines compliance after the initial intervention was not always possible.

The majority of patients who received a polypharmacy review (71% [n=78]) already used an MCA to take their medicines. Some patients required a medicine prompt and/or supervision as part of their care package, where a social carer would visit them to ensure they take it appropriately. In this group of patients, adherence to medicines was found to be good and, if a dose had been missed, it was easy to notice and identify trends. However, in some patients, non-compliance was evident with regular missed doses and confusion about medicines, which lead to poor adherence. This trend was picked up during a face-to-face level 3 review. Out of the total number of patients eligible for a full level 3 review (n=110), 6% of patients (n=7) had compliance issues, these ranged from omitting medicines periodically to frequently missing doses; and nearly 3% of patients (n=3) had a new MCA arranged with a local pharmacy and new prescriptions provided for weekly dispensing following their review.

Inhaler review

A review of inhaler technique was performed with each patient with asthma or COPD. Of patients with inhalers, 69% (n=21) demonstrated inappropriate technique or poor dexterity, both of which were more common in patients aged over 75 years. However, a low rate of attendance at annual respiratory reviews was also noted for all patients with poor inhaler technique. As a result, inhaler technique counselling was provided during the review. Inhaler devices were also switched in line with guidelines, where appropriate. In cases of poor dexterity, a simple switch from multi-dose inhaler (MDI) to a dry powder Easyhaler helped patients; alternatively, they were provided with spacer devices to aid MDI inhalation. By improving inhaler technique and ensuring the majority of the dose is being administered appropriately, the risk of exacerbations was reduced[26]

. With more stable respiratory symptoms, it is hoped that quality of life would also improve, while reducing attendance at GP appointments and reducing other forms of unscheduled care, such as attending an accident and emergency department.

Patient engagement

The SIMD identified Govan as being among the top 5% of the most deprived areas in Scotland[17]

. Figure 1 indicates that the greatest percentage of patients receiving pharmacy reviews were within the most deprived quintile, which is similar to the profile of the overall population of the surgeries in this study. This supports the theory that those who are requiring the most interventions are from the most socio-economical deprived communities[1],[27]

.

Despite traditional search tools such as SPARRA/STU not being used to identify patients, Figure 1 shows that appropriate patients were identified based on deprivation, and that the majority of patients were aged over 65 years. However, there was no measurement of frailty.

Patient engagement was challenging when arranging polypharmacy review appointments. From the 151 patients that were offered a pharmacist review, 5% of patients (n=7) refused and a further 8% of patients (n=12) failed to attend, despite agreeing to.

In the case of missed appointments, attempts were made to reschedule or perform a telephone consultation, if appropriate. If this was not possible, details of desktop review findings would be entered on GP medical records for information for the GP. For urgent issues, changes were made and contact with the patient made via telephone and/or letter.

Community pharmacy

The 2017 Scottish government publication, ‘Achieving excellence in pharmaceutical care: a strategy for Scotland’, stated that one of its aims was to increase “access to community pharmacy as the first port of call for managing self-limiting illnesses”[27]

. Community pharmacy is an essential provider of services and up to 10% of patients who undertook a SHIP review were referred to services such as the MAS, NRT and Pharmacy First. Within this patient group, awareness of community pharmacy services was particularly low, as stated by patients or their carers. It was also found that families with young children were commonly presenting at GP and out-of-hours services for ailments that could have been appropriately treated by their community pharmacy (e.g. conjunctivitis and rashes in children, and symptoms of urinary tract infection in mothers). To help raise awareness of community pharmacy, social work and health visitors were updated and informed of current community pharmacy services because of their frequent contact with parents and children.

To improve patient experiences with community pharmacy, it is imperative that there is good communication between GP practices and community pharmacies. During the project, local community pharmacies were visited by the SHIP pharmacist to gather feedback on their current communication with GP surgeries. The feedback showed that a common theme was lack of information when changes were made to MCAs that could result in medicine errors, which in turn could result in a patient safety risk. The most common reason for a referral to pharmacy from a GP owing to MCAs, indicating the importance of good communication between community pharmacy and GP practices. This issue was discussed with surgery teams to ensure all changes to a patient’s medicines regimen were being communicated to the community pharmacy as per existing primary care standard operating procedures.

Social prescribing

The SHIP project facilitated a closer working relationship between the different members of the MDT, resulting in a more efficient process of referring patients to appropriate healthcare professionals. The pharmacist attended monthly MDT meetings to discuss complex cases, to inform MDT colleagues of interventions made and to gain input from the medical and nursing team. This also provided an opportunity for the pharmacist to refer patients to the attention of social work or community links practitioners. This highlighted the importance of close working within the MDT and the role pharmacists can play in identifying patients for social support — effectively a ‘social prescription’[28]

.

The physiotherapist also referred patients who were taking a combination of analgesics and treatments for mental health conditions, for level 3 polypharmacy review when they noticed during consultation that the patient was not managing their medicines well or was taking several complex or high-risk medicines. Similarly, during home visits, the community links practitioner identified patients with medicine issues and refer them to the pharmacist for a review, demonstrating the important roles of all MDT members in identifying patients who may be having difficulty with their medicine. The flow of referrals meant that patients received input from appropriate members of the MDT without having to continually seek GP assessment and onward referrals. As the role of the pharmacist was established within the MDT, the number of direct referrals being received from all members of the MDT increased. This indicated that having a pharmacist as part of the team reduces barriers to communication and raises awareness of the benefit of pharmacist polypharmacy reviews.

Home visits

A large proportion of SHIP patients were housebound, therefore of those who received a level 3 polypharmacy review (n=88), 37% (n=33) were performed as home visits. Housebound patients are at the highest risk of complications and are often vulnerable and socially isolated. Practice pharmacists rarely have the opportunity to visit these patients, meaning it was particularly useful to see these patients at a time when they did not have acute symptoms. Home visits provided additional benefits because the pharmacist was able to assess issues that otherwise would not have been detectable, such as medicine storage, falls risk and social circumstances.

As a result, medicine storage advice was provided and changes to social work care packages were implemented where patients required further support with medicines. It was also found that housebound patients are more likely to have outstanding observations, tests and/or monitoring needs. The pharmacist was able to carry out a BP/pulse check and request blood tests from the district nurse, where required.

Unmet health needs

Of all referred SHIP patients, 33% (n=104) were not prescribed medicines. However, during pharmacy screening, unmet health needs were considered where investigations and medicines were initiated as appropriate. As a result, two patients were prescribed medicine for previously undiagnosed hypertension and one patient resumed a medicine that had previously been started by secondary care, but had since lapsed. This finding shows the importance of regular reviews in which the pharmacist can carry out proactive observations that at the very least can be used as a baseline for future observations or could be used to pre-empt potential issues.

In 2008, Kuipers et al. found a link between polypharmacy and underprescribing whereby it was thought that when a patient is taking a large number of medicines, prescribers may be less likely to prescribe further medicine[28]

. However, the study included an older, geriatric population and, in this way, differs from the SHIP project. These findings indicate that unmet needs should always be considered in a medication review. Also, START offers a strategy to reduce underprescribing[12]

.

Transferability

One aim of the Govan SHIP project was to understand the potential for scalability and transferability. The project was explicitly set within the context of socio-economic deprivation; however, the findings suggest that this type of review process could be transferred to any locality, irrespective of demographic profile. Patient selection for screening is universal, allowing varying types of patients to be included. An experienced independent prescribing pharmacist is required and could integrate into any existing practice or local MDT. This new model of working fits well as an elective element of the new pharmacotherapy service envisaged by the 2018 General Medical Services contract in Scotland[29]

.

Clinical effectiveness

Although no formal feedback was sought from patients following their medication review, most patients volunteered informal feedback. While feedback was not recorded, reports from those involved in the project indicated that it was overwhelmingly positive. Pharmacist input was evidently valued by patients by way of informal feedback and the MDT by way of informal feedback.

Seven members of the MDT — a representative cohort of the full team — provided feedback via survey, five of whom indicated that pharmacist input was ‘excellent’. All respondents found pharmacist input into team meetings to be useful, which demonstrates that pharmacists should be fully integrated members of the MDT in order to support the healthcare team in managing complex patients. Not only did interventions increase patient safety, they also increased prescribing cost-effectiveness.

The long-term benefit of these reviews may be significant for the patient, (e.g. reduction in falls and fractures, improvement in cognition etc.); however, significance was not measurable within the scope of this project.

Limitations

This was a medium-scale local project within one locality of Glasgow and referrals were only from within the participating primary care practices. There was not enough scope or resources to allow for secondary care referral as described in the Lewisham Integrated Medicines Optimisation Service — or LIMOS — study, which was able to provide an interface between primary and secondary care, helping with seamless patient care[30]

. If more time was granted, further awareness of the project within secondary care and perhaps scope for secondary care referral would have been made. Self-referral was not considered in this study owing to concerns that the resources may be utilised by frequent attenders and as is common in deprived areas, the most in need of support are least likely to seek it[6]

.

Owing to the short duration of the project, it was not possible to evaluate the long-term effects of the reviews in certain scenarios, such as asthma exacerbations; medicines-related hospital admissions; frequency of GP appointments; and unscheduled care presentations. In addition, although this method of pharmacist intervention is transferrable, the results may not be reproducible as the impact will depend on existing prescribing practices; therefore, there may be more/less scope for intervention. The impact could be even greater in areas where there is little or no pharmacy support.

The MDT questionnaire asked three questions to make it quick and simple to use for the respondents, which also helped improve response rate. For a more thorough review of pharmacist input, more in-depth questioning may have been used. There was positive and useful informal feedback received from patients and the pharmacy teams, but this was not collated formally. Patient feedback may have provided a good indicator for impact that pharmacists can make and could be an area of further research.

Conclusion

The inclusion of a pharmacist within the SHIP project is in line with commitment two of the Scottish government’s ‘Achieving excellence in pharmaceutical care: a strategy for Scotland’, which aimed to integrate pharmacists with advanced clinical skills and pharmacy technicians in GP practices to improve pharmaceutical care and contribute to the MDT[27]

. The interventions made by the pharmacist not only addressed immediate concerns, but also contributed towards preventative care, helping to reduce GP workload and ensures that pharmacists are utilising their skills as medicines experts, reducing unwanted medicines reduces tablet burden as well as reducing risk of toxicity. Within this group of patients, deprescribing was found to be a common intervention. This is an area of current interest and requires further research. The results and feedback from patients and members of the MDT reaffirm that pharmacists have an important role in ensuring excellent pharmaceutical care for patients.

About the authors

Rizwan Din is a prescribing support pharmacist at NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Glasgow South (now NHS Lanarkshire); Colette Montgomery Sardar is part of the research and development team at pharmacy services for NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde; Graeme Bryson is the lead pharmacist at NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde, Glasgow South (now D&G); and Vince McGarry is project manager at Govan Social and Healthcare Integration Partnership project, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde

- The ‘Results’ section of this article was updated on 15 May 2020 to further clarify the number of patients analysed in each of the review populations, as well as the related percentages.

References

[1] Scottish Government Polypharmacy Model of Care Group. Polypharmacy Guidance, Realistic prescribing, 3rd edition, 2018. Scottish Government. 2018. Available at https://www.therapeutics.scot.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Polypharmacy-Guidance-2018.pdf (accessed May 2020)

[2] Information Services Division (ISD), NHS National Services, Scotland. 2020. Available at https://www.isdscotland.org/ (accessed May 2020)

[3] Mahmoud A. Scottish patients at risk of readmission and admission (Sparra). Int J Integr Care 2016;16(6):A216. doi: 10.5334/ijic.2764

[4] Barnet K, Mercer SW, Norbury M et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012;380(9836):37–43. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2

[5] NHS Scotland. Improvement Hub, Healthcare Improvement Scotland, Frailty and the electronic frailty index. 2019. Available at: https://ihub.scot/media/6106/frailty-and-the-electronic-frailty-index.pdf (accessed May 2020)

[6] Tudor Hart J, The Inverse Care Law. Lancet 1971;297(7696):405–412. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(71)92410-X

[7] Scottish Government Statistics. Geographical Statistics. 2018. Available at: http://statistics.gov.scot/id/statistical-geography/S13002971 (accessed May 2020)

[8] Watt G, Brown G, Budd J et al. General Practitioners at the Deep End: The experience and views of general practitioners working in the most severely deprived areas of Scotland. Occas Pap R Coll Gen Pract 2012;89:1–40. PMID: 27074888

[9] Harris F, McGregor J, Maxwell M & Mercer S. A Qualitative evaluation of the Govan SHIP, A Social and Healthcare Integration Partnership project. Nursing, Midwifery and Allied Health Profesionals Research Unit. 2017. Available at: http://www.sspc.ac.uk/media/media_587367_en.pdf (accessed May 2020)

[10] Nightingale G, Hajjar E, Swarz K et al. Evaluation of a Pharmacist-Led Medication Assessment Used to Identify Prevalence of And Associations with Polypharmacy and Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use Among Ambulatory Senior Adults With Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015;33(13):1453–1459. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.7550

[11] NHS Brent Clinical Commissioning Group (2014). Medicines Optimisation: Clinical Medication Review. A Practice Guide. 2014. Available at: https://www.sps.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Brent-CCG-Medication-Review-Practice-Guide-2014.pdf (accessed May 2020)

[12] O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S et al. STOPP/START Criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing 2015;44(2):213–218. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu145

[13] Fox C, Richardson K, Maidment ID et al. Anticholinergic Medication Use and Cognitive Impairment in the Older Population; The Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011;59:1477–1483. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03491.x

[14] King R & Rabino S. The Anticholinergic Burden Calculator. Available at: http://www.acbcalc.com (accessed May 2020)

[15] University of Nottingham & EMIS. QRISK3 cardiovascular risk calculator. ClinRisk. 2018. Available at: https://www.qrisk.org/three (accessed May 2020)

[16] Fracture Risk Assessment Tool. Centre for Metabolic Bone Disease. University Of Sheffield. Available at: https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.aspx?country=1 (accessed May 2020)

[17] Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD). Scottish Government & Ordinance Survey Data. 2016. Available at: http://simd.scot/2016/#/simd2016/BTFTTTT/14/-4.3265/55.8604 (accessed May 2020)

[18] Pirmohammed M, James S, Meakin S et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admissions to hospital; prospective analysis of 18,820 patients. BMJ 2004;329(7456):15–19. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7456.15

[19] Leendertse AJ, Egberts AC, Van Den Bemt PM et al. Frequency and risk factors for preventable medication-related hospital admissions in the Netherlands. Arch Int Med 2008;168(17):1890–1896. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.3

[20] Reeve E, Gnijidc D, Long J & Hilmer S. A systematic review of the emerging definition of “de-prescribing” with network analysis: implications for future research and clinical practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2015; 80:1254–1268. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12732

[21] Garfinkel D, Ilhan B & Bahat G. Routine deprescribing of chronic medications to combat polypharmacy. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2015;6(6):212–233. doi: 10.1177/2042098615613984

[22] Reeve E, Wolff JL, Skehan Met al. Assessment of attitudes toward deprescribing in older Medicare beneficiaries in the United States. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178(12):1673–1680. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4720

[23] Bell JS, Airaksinen MS, Lyles A et al. Concordance is not synonymous with compliance or adherence. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2007;64(5):710–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02971_1.x

[24] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Medicines adherence: Involving patients in decisions about prescribed medicines and supporting adherence. Clinical guideline [CG76]. 2009. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG76 (accessed May 2020)

[25] Brown M & Bussell J. Medication Adherence: WHO Cares? Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2011;86(4):304–314. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0575

[26] Al-Jahdali H, Ahmed A, Al-Harbi A et al. Improper inhaler technique is associated with poor asthma control and frequent emergency department visits. Allergy Asthma Clinl Immunol 2013;9(8). doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-9-8

[27] Scottish government. Chief Medical Officer Directorate Achieving excellence in pharmaceutical care: a strategy for Scotland. 2017. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/achieving-excellence-pharmaceutical-care-strategy-scotland/pages/3 (accessed May 2020)

[28] Kuipers MAJ, van Marum RJ, Egberts ACG et al. Relationship between polypharmacy and underprescribing. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2008;65(1):130–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02961.x

[29] Scottish government. Population Health Directorate. General Medical Services contract in Scotland. 2018. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/gms-contract-scotland/pages/14 (accessed May 2020)

[30] Lai K, Howes K, Butterworth C & Salter M. Lewisham Integrated Medicines Optimisation Service: delivering a system-wide coordinated care model to support patients in the management of medicines to retain independence in their own home. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2014;22(2). doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2014-000565