Key points

- Domiciliary visits by pharmacy professionals are shown to result in better medicines safety, leading to reduced hospital admissions with associated cost efficiency.

- Similar published services have reported improved medicines safety and cost savings of £200,000—£300,000, staffed with modest-sized teams.

- Domiciliary visits benefit vulnerable people that are unlikely to access existing community pharmacy advanced services.

- An enhanced service can be commissioned, facilitating work to support the vulnerable to take their medicines more effectively.

- Assistive technology devices, such as the Pivotell Advance (Pivotell Ltd) and the MemRabel 2 (Pivotell Ltd), show promise in prolonging patient independence in taking their medicines and may reduce social care costs in certain circumstances. However, further data in this setting are required.

Introduction

As recognised in the Murray report, the main intervention used for people living with long-term conditions is medicine[1]

.

Therefore, it follows that optimised medicines will contribute to better outcomes for this group of people. The ‘NHS long-term plan’ also recognises the benefits of treating more people at home and highlights the role of technology in achieving this[2]

.

Therefore, patients across the UK — particularly vulnerable, older patients, as well as those at the interface of primary and secondary care — are increasingly receiving pharmaceutical care in their own home by pharmacy teams.

Example services include the Lewisham integrated medicines optimisation service (LIMOS), Exeter cluster pharmacy (ECP), the community complex care pharmacist and the proactive care pilot (PCP)[3],[4],[5],[6]

.

The LIMOS and the community complex care pharmacist pilot are driven by hospital pharmacists devoting time to interact with community services. They can offer an in-reach service and attend multidisciplinary team meetings where they see the patient from being an inpatient to returning home[3],[5]

. In contrast, pharmacists involved with ECP and the PCP worked in a primary care setting and attended multidisciplinary team meetings[4],[6]

.

A common feature of these services is the involvement of health and social care stakeholders. Each service reports positive outcomes from providing domiciliary visits to patients, for example, a reduction in medicines-related hospital admissions and prescribing costs following a medicine review.

The relatively small teams involved — the PCP used a part-time pharmacist 0.2 whole-time equivalent [WTE], while LIMOS used four pharmacists and two pharmacy technicians — appear to represent value for money, covering clinical commissioning group (CCG)-sized populations, while generating £200,000—£300,000 in savings[3],[6]

.

A domiciliary pharmacy service

In 2008, Portsmouth CCG commissioned a new role for a domiciliary pharmacy service — the intermediate care pharmacist. Initially tasked with looking after patients struggling with their medicine in the intermediate care period (i.e. between hospital and home), the role has since been developed.

Owing to the 2012 organisational changes in the NHS, where primary care trusts dissolved in favour of CCGs, the domiciliary pharmacy service is hosted by Solent NHS Trust and is known as the ‘medicines advice at home’ (MAH) service[7]

. Solent became the host in order to separate commissioner and provider roles with Portsmouth CCG. The name change was made in consultation with the Portsmouth CCG communications team to make the purpose of MAH clearer to the public.

The Solent NHS Trust provides community-based NHS services across a footprint that stretches from Southampton to Portsmouth. It was, therefore, a natural home for the MAH service even though the boundaries that Solent shares with Portsmouth CCG are not coterminous. Despite its home in Solent, MAH is commissioned to serve only Portsmouth CCG’s patients, of which there are an estimated 215,000 on GP lists[8]

.

The MAH service consists of one full-time and two part-time pharmacists (2.6 WTE), one full-time and two part-time pharmacy technicians (1.7 WTE), and one part-time administrator (0.5 WTE).

The service uses the principles of medicines optimisation to provide support for any individual with problems taking their medicines[9]

.

This includes: medication review, synchronising medicines, auditing medicines taken with GP-held records, compliance cards, one-off aids, monitored dosage systems (MDSs; also known as multicompartment compliance aids [MCAs]) and assistive technology.

Referrals to the MAH service come from GPs, social workers and allied healthcare professionals. Patients started on new MCAs are also referred by local hospitals to facilitate continuation at their usual pharmacy. There are no age constraints on patients referred to the service.

Portsmouth Clinical Commissioning Group ‘concordance’ community pharmacy local enhanced service

Currently, community pharmacy is expected and able to make reasonable adjustments to help a person with their medicines, in accordance with the Equality Act 2010[10]

. However, regular ongoing patient support, which is not within the regular NHS terms of service, has often been identified as the best option for many scenarios. This support may include the provision of medicine administration record (MAR) charts or MCAs with additional monitoring for individual patients. In recognition of this, Portsmouth CCG commissioned a locally enhanced service to pay for additional activity from community pharmacies, supporting the work of MAH.

Known locally as the ‘concordance’ service, it was developed to facilitate the MAH team to provide enhanced support for individual patients in taking their medicine[11]

. The service remunerates the ongoing supply of medicine recording charts and MCAs from pharmacies, against a 28-day prescribing period, for patients who have been appropriately assessed as in need of this level of support. From the CCG perspective, a reduction in the number of 7-day prescriptions, with the assurance that patients are assessed consistent with the Equality Act, are welcome outcomes.

The concordance service remuneration system for participating pharmacies has payment levels that reflect the costs associated with supplying different compliance aids and the varying need for ongoing patient support. The community pharmacy receives referral paperwork from the MAH service, which describes the support required and enables the pharmacy to claim its fee via the PharmOutcomes platform. The levels are as follows:

- Level 1 — requests the pharmacy to provide MAR charts to support the patient or their carer;

- Level 2 — requests provision of MCAs. The fee can be claimed if it is dispensed against a 28-day prescription (weekly supply can still be requested by MAH against the 28-day prescription);

- Level 3 — requests provision of medicines in a Pivotell Advance (Pivotell Ltd) automatic pill dispenser, for the pharmacy to regularly re-supply. Fees increase in proportion with the frequency of supply and are not tied to prescription duration.

At inception, all community pharmacies in Portsmouth signed up to provide the Level 1 and Level 2 locally enhanced service. Level 3 was subsequently designed and offered by geographic spread to a smaller number of providers who expressed an interest to supply. Fewer providers were commissioned to concentrate the expertise needed to deal with more complex devices, thereby mitigating any associated risks with supply, bearing in mind the proportionally small number of people referred.

‘Medicines advice at home’ service

Most patients referred to the MAH service receive an initial visit from a pharmacist to discuss how to optimise their medicines.

Follow-up visits are arranged as necessary with the pharmacist or technician to check how the patient is coping with the initial intervention(s). Pharmacy technicians verify and manage the process of any changes to medicines by communicating with prescribers and the patient’s usual pharmacy. The technicians also make follow-up visits to any new patient with an MCA discharged from hospital because their prescriptions have already been screened by a hospital pharmacist. Reports are written to the patient’s GP and the original referrer is kept up to date. The patient is discharged after appropriate follow-up and referred onward when necessary or if MAH interventions are unsuccessful.

Assistive technology

The benefits of using assistive technology to support patients with taking their medicines were explored by Portsmouth City Council in a small unpublished pilot. The commissioners decided that assistive technology devices have the potential to reduce a burden, which would otherwise fall on people caring for a patient, in either an official (funded) or unofficial capacity.

Various AT devices have been used as part of the MAH service since its inception. As a result of experience and patient feedback, only two devices are currently in use: the MemRabel 2 (Pivotell Ltd)[12]

and the Pivotell Advance[13]

. These remain the property of MAH and are issued on loan to those patients who may benefit from their use.

Aims

This study aimed to evaluate the MAH service.

Methods

Patient demographics

Throughout the 2017/2018 calendar years, details of all referrals to the MAH service were recorded in an Excel spreadsheet stored on a network drive for all members of the team to access. Once the patient had been visited, data about the consultation was entered contemporaneously to record the initial state of their medicines and a risk rating was assigned. The captured information includes patient demographics, the number of medicines they are prescribed and how complex the regime is to take (defined as ≥5 medicines in multiple doses per day or >12 doses per day in total).

Risk matrix

Upon follow-up and discharge, the patient’s risk rating was recalculated and recorded in the Excel spreadsheet for comparison via pivot tables (to provide tables and graphs).

Within MAH, the effectiveness of interventions were rated based on the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) risk descriptors used by LIMOS, ECP and the PCP[14],[15]

. Unlike the work of Dilks et al. or Dowell, a second person/higher band sample review of the ratings was not extrapolated to the results as a whole, primarily owing to the number of referrals seen by the MAH service[4],[6]

. Noting that agreement upon review had been reported by others as high, albeit on a small sample, it was decided to report figures with no adjustment. The MAH service pharmacists each had at least 15 years of practice experience and were expected to rate the risks accurately.

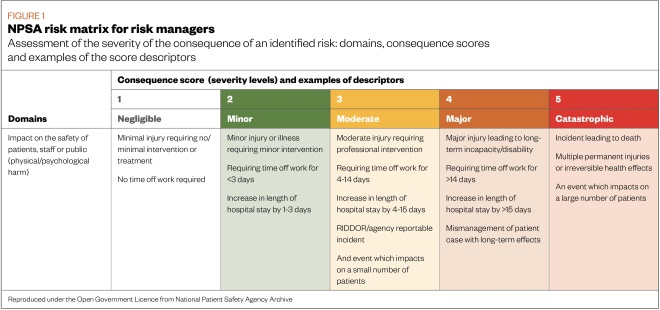

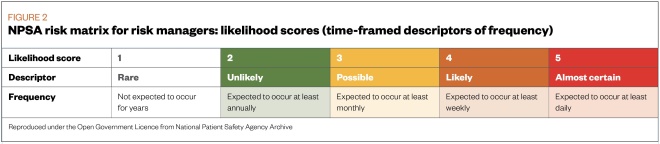

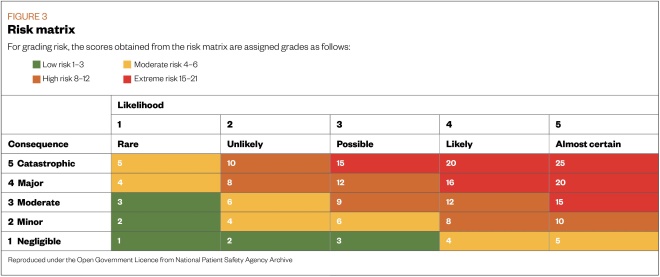

To determine a patient’s risk score, the NPSA risk descriptors were used. First, a ‘severity of impact’ score of 1 to 5 (where 1 is negligible and 5 is catastrophic) is assigned (see Figure 1). Second, a likelihood of occurrence score (where 1 is rare and 5 is almost certain) is assigned (see Figure 2). The two scores are then multiplied together, with the product number being stratified to further descriptors (i.e. low-extreme; see Figure 3). Put simply, risk is the consequence multiplied by the likelihood of it happening.

Figure 1: NPSA risk matrix for risk managers

Figure 2: NPSA risk matrix for risk managers likelihood scores

Figure 3: Risk matrix

The same method of Dilks et al. was used[2]

. In their method, they approximated that patients whose risk score was reduced from ‘extreme’ (score ≥ 15) to a lower category (score <15) were likely to have had an admission to hospital prevented[2]

. Their tool is not validated, but it provides a useful indication of the service value. The ‘Fit for frailty: part 2’ document discusses how it is difficult to practically measure the effect of intervention in section 3 of the guidance[16]

.

Assistive technology

The two devices used in MAH to support patients with taking their medicines are:

MemRabel 2— a talking alarm clock. It runs the Android operating system and occupies the footprint of a digital photo frame. It must be plugged in at the mains to function. Up to 20 daily alarms can be set to provide a verbal prompt to the patient to take their medication.

In its normal state, the clock can be set to display a combination of day, date, time and time descriptor. This can help orient a person to date and time, which is helpful in forgetful patients, patients with dementia or patients in whom strict adherence to a regimen is important.

Pivotell Advance— a circular, plastic, clamshell device containing the electronic and mechanic capability to present medication to a patient at predetermined times. Within the clamshell, a multicompartment carousel is inserted containing sequential doses.

At programmed alarm times, the device rotates the due dose to a shutter in the lid of the device. A sensor detects that the device has been tipped upside-down to obtain the medication and tipped back upright, which closes the shutter until the next dose is due.

A ‘Tipper’ device is also available, which functions as a spring-loaded cradle to assist patients lacking the manual dexterity or strength to tip the device themselves (e.g. patients with Parkinson’s disease). The Pivotell Advance can be useful in situations where the patient may have a history of being unable to manage a traditional MCA (e.g. inadvertent over-use) because it prevents accidental extra doses.

However, a trial period should always be carried out because patients are still able to pry or break the device open. Unfortunately, not all patients who might benefit are able to demonstrate they can use the device safely during a trial.

Results

Patient demographics

There were 600 referrals to the MAH service in 2017 and 754 referrals in 2018. Referrals to the MAH service were from GPs, social workers and the allied healthcare professionals. Patients started on new MCA were also referred by local hospitals to facilitate continuation at their usual pharmacy. There were no age constraints on patients referred to the service. However, 85% of referrals were for patients aged over 60 years. These vulnerable patients were often housebound or unlikely to be able to visit their community pharmacy. A proportion of referred patients had dementia with attendant difficulty in managing medication.

However, the numbers of complete records are lower than the raw referral numbers, owing to various reasons, including duplicate referrals (e.g. from a GP and a mental health nurse for the same patient) and patient refusal. Therefore, 512 complete records were made in 2017 and 555 complete records were made in 2018.

In 2017, referrals were most frequent in patients aged 80–90 years. As the age bands descend, so too did the frequency of referral. Of the 536 patients initially seen, 61% (n=327) were female, which may reflect more females reaching advanced age within the population. At least 59% (n=318) patients lived alone, 37% (n=199) patients were housebound and 4% (n=20) unable to get out without help. Similar proportions are seen in the 2018 data, giving an overall impression of the vulnerabilities seen in the CCG population.

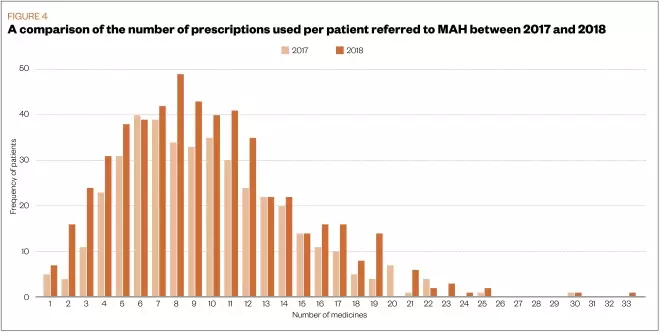

The number of medicines used by patients at the point of an initial visit from MAH ranged from 1 to 30 in 2017 data and 1 to 33 in 2018. In a plot of the number of patients versus the number of medicines they were taking, distributed along a skewed bell, the mode was six medicines in 2017 and eight in 2018. The frequency of patients having more prescriptions than this begins to decrease above ten items per patient (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Comparison of the number of prescriptions used per patient referred to MAH 2017 and 2018

Polypharmacy contributed to complex regimens that were difficult to manage for the vulnerable people referred to the MAH service. Overall, 54% of the patients were noted as having a complex regimen in 2017 and 52% in 2018.

Risk matrix

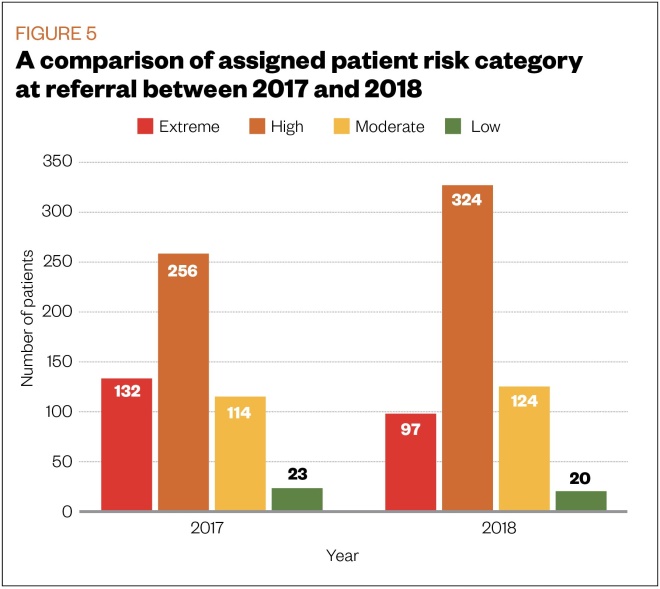

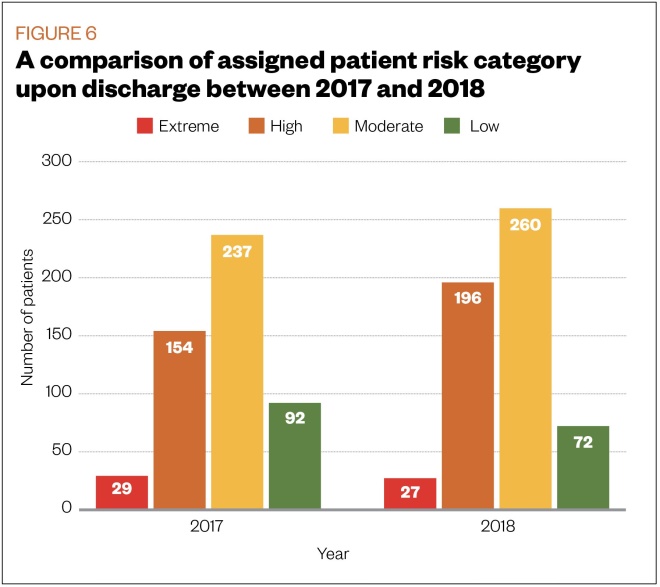

Figures 5 and 6 show that during both 2017 and 2018 the MAH interventions were effective in reducing risks to the patients from their medicines. Overall, the ‘extreme’ and ‘high-risk’ columns were reduced, while the ‘moderate’ and ‘low-risk’ columns increased at discharge compared with referral.

In 2017, 20% (n=103) of the total number of patients (n=512) that were scored twice began with an extreme risk that was reduced (i.e. 20% of patients referred and seen were prevented from a likely admission; 1% [n=7] of the patients who were scored twice used Pivotell). In 2018, 13% (n=70) of the total number of patients (n=555) that were scored twice, began with an extreme risk that was reduced (i.e. 12% of patients prevented from hospital admission; 1% [n=5] of the patients who were scored twice used Pivotell). Figure 5 illustrates that fewer patients in 2018 were assessed by the MAH service at an initial extreme risk rating (with a commensurately larger number of ‘high-risk’ patients) than in 2017.

By considering only the patients initially rated as extreme, the effectiveness of MAH intervention between 2017 and 2018 appears more comparable. Overall, out of 132 patients rated as having an extreme risk at referral in 2017, 78% (n=103) patients had their risk reduced, while out of 97 patients with extreme risk at referral in 2018, 72% (n=70) patients had their risk reduced.

Figure 5: Comparison of assigned patient risk at referral

Figure 6: A comparison of assigned patient risk category upon discharge

Assistive technology

The number of people using MemRabel 2 (n=35 in 2017; n=25 in 2018) is larger than that of Pivotell (n=14 in 2017; n=18 in 2018), however, they are a relatively small proportion of patients referred to MAH overall.

Discussion

The recent roles created in care homes for pharmacists with the pharmacy integration fund demonstrate an understanding by NHS England of how advantageous the use of the profession can be[17]

. These data show that there are many vulnerable older people still living at home who can benefit from some domiciliary pharmaceutical care.

The author notes that the characteristics or common traits of patients living in a care setting overlap strongly with those that could benefit from a domiciliary visit (e.g. vulnerability, age, frailty, polypharmacy and non-adherence). Typically, both groups would be unable to easily access the services of their local community pharmacy. Covering this gap in pharmaceutical care by sending pharmacy professionals to patients whether in a care or domiciliary setting, can only serve to improve the standard of care. The risk score reductions shown by the MAH service directly demonstrate an improvement in medicines safety.

Dilks et al. extrapolated a cost-saving of £242,642 from admission avoidance[4]

. The MAH service compares well using the same figure to extrapolate on its 2017 data of a potential saving of £250,290 from admission avoidance and £170,100 in 2018. Savings to the healthcare economy undoubtedly also accrue from prevented waste and prevented care visits. Dowell estimated an extrapolated CCG-wide saving in 2013 of £354,000 with the costs of the pilot covered by reduction in prescribing alone[6]

.

The work of others has shown “that prevention of medication-related readmissions can be cost-effective”[18]

. Acknowledging the workload pressure faced in secondary care leads to the conclusion that ‘admissions avoided’ are not cash releasing. Rather, the cost-saving figures quoted above is money more appropriately spent on patients who went to hospital.

In this context, use of a risk rating system as a proxy for admissions avoidance seems to be a reasonable method for approximating the effectiveness of pharmacy intervention. Especially considering the difficulties faced trying to measure the effectiveness of an intervention in preventing an outcome that may or may not happen when weighed against the subjectivity of the rating. A potential saving of £200,000—£300,000 from reduced hospital admissions could be achievable with relatively small numbers of pharmacy professionals.

Limitations

The limitations with the methodology have been mentioned within the text used but it is acknowledged that the risk ratings have not been validated.

Using the NPSA descriptors helped with objectivity when providing patients with a risk matrix; however, it is acknowledged that the process of risk rating can be a subjective exercise.

There is also only a small amount of data about the use of AT devices from which to draw a conclusion. Therefore, further qualitative and quantitative data are needed regarding AT devices and how much they reduce patients’ risk.

Conclusion

As the work of the local sustainability and transformation plans (STP) moves forward[19]

, there could be a case for including a role for pharmacists undertaking domiciliary visits in addition to the work underway in care homes. Work at the Northumberland vanguard has shown what this might look like with a service that also reports excellent cost-effectiveness[20]

.

Newly formed primary care networks (PCNs) within each area covered by an STP may decide to deploy their clinical pharmacists to undertake domiciliary work, depending upon the geography of the areas they cover.

Alternatively, given the population coverage achieved by the small teams cited, resources could be pooled to achieve scale. While PCNs are still in the process of getting started, it would appear to be an opportune time for pharmacy teams to engage, promote their work, and influence how pharmacy services in their locality are commissioned — including but not limited to, domiciliary visits.

The use of assistive technology devices appears to support the ‘NHS long-term plan’ and its vision of more technological interaction with the patient. In expectation of innovation and more mainstream assistive technology use, it may be easier to create an evidence base for their appropriate use in the future.

Financial and conflicts of interest disclosure

The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. No writing assistance was used in the production of this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to acknowledge our former commissioning lead Janet Bowhill (retired) of Portsmouth CCG for suggesting the methodology and my colleagues in the MAH team Judith Bruell (retired), Jenny Winfield, Janice Gunby, Sarah Newman, Angela Hughes, EmmyLou Shergold, Sue Bearman and Amanda Jennions for helping collect the data.

References

[1] Murray R. Community pharmacy clinical services review. 2016. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2016/12/community-pharm-clncl-serv-rev.pdf (accessed November 2019)

[2] NHS. The NHS long-term plan. 2019. Available at: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-plan (accessed November 2019)

[3] Lai K, Howes K, Butterworth C et al. Lewisham integrated medicines optimisation service: delivering a system-wide coordinated care model to support patients in the management of medicines to retain independence in their own home. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2015;22(2):98–101. doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2014-000565

[4] Dilks S, Emblin K, Nash I & Jefferies S. Pharmacy at home: service for frail older patients demonstrates medicines risk reduction and admission avoidance. Clin Pharm 2016;8(7):217–222. doi: 10.1211/CP.2016.20201303

[5] Brown L, Gitonga N & Mayahi L. Complex care management medicines optimisation. 2017. Available at: https://www.acutemedicine.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/SOD-02.pdf (accessed November 2019)

[6] Dowell G. Pharmacists can help reduce avoidable hospital admissions in the community. Pharm J 2013;291(9):287. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2013.11128324

[7] Portsmouth Clinical Commissioning Group. Community Pharmacy South Central. 2019. Available at: https://www.cpsc.org.uk/application/files/2815/5604/0516/Concordance_Level_1__2_2019-21.pdf (accessed November 2019)

[8] Portsmouth Clinical Commissioning Group. Portsmouth Clinical Commissioning Group: who we are and what we do. 2019. Available at: https://www.portsmouthccg.nhs.uk/About-Us/who-we-are-and-what-we-do.htm (accessed November 2019)

[9] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Medicines optimisation: helping patients to make the most of medicines. 2013. Available at: https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Policy/helping-patients-make-the-most-of-their-medicines.pdf (accessed November 2019)

[10] Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. The Equality Act 2010. 2017. Available at: https://psnc.org.uk/contract-it/pharmacy-regulation/dda (accessed November 2019)

[11] Portsmouth Clinical Commissioning Group. Schedule 2 — the services. 2016. Available at: https://www.cpsc.org.uk/application/files/7115/1283/1152/ConcordanceLevel12_16_18.pdf (accessed November 2019)

[12] Pivotell. MemRabel 2. 2019. Available at: https://www.pivotell.co.uk/MemRabel+2/0_CAAA002/PRAA024.htm (accessed November 2019)

[13] Pivotell. Pivotell Advance Dispenser. 2019. Available at: https://www.pivotell.co.uk/PivoTell+Advance+Dispenser/0_CAAA001/PRAA001.htm (accessed November 2019)

[14] National Patient Safety Agency. A risk matrix for risk managers. 2008. Available at: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110223084700/http://www.npsa.nhs.uk/EasysiteWeb/getresource.axd?AssetID=7252&type=Full&servicetype=Attachment (accessed November 2019)

[15] Howes K. Medicines optimisation — an integrated approach in Lewisham. 2016. Available at: https://www.sps.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Presn_CHS_7_Jun_2016_LIMOS_MO_in_Lewisham_KH.pdf (accessed November 2019)

[16] British Geriatrics Society and Royal College of General Practitioners. Fit for frailty. Part 2: developing, commissioning and managing services for people living with frailty in community settings. 2015. Available at: https://www.bgs.org.uk/sites/default/files/content/resources/files/2018-05-23/fff2_full.pdf (accessed November 2019)

[17] NHS England. Medicines optimisation in care homes. 2019. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/primary-care/pharmacy/medicines-optimisation-in-care-homes (accessed November 2019)

[18] Barnett N & Blagburn J. Reducing preventable hospital readmissions: a way forward. Clin Pharm 2016;8(1):2–3. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2016.20200365

[19] The King’s Fund. Sustainability and transformation plans (STPs) explained. 2017. Available at: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/topics/integrated-care/sustainability-transformation-plans-explained (accessed November 2019)

[20] Bakir W, Paes P, Stoker A et al. Impact of an integrated pharmacy service on hospital admission costs. Clin Pharm 2018;10(5):155–160. doi: 10.1211/CP.2018.20204550