Introduction

The increasing demand in healthcare, urgent care and emergency care; the increasing numbers of frail elderly, in particular the care home population; increasing polypharmacy associated with comorbidities and evidence-based medicine protocols; along with increasing workforce pressures and demand for primary medical care services mean a new approach to the use of pharmacy services is required. This article describes recent developments within Northumberland, a county in north-east England with a population of around 320,000 people, where there has been a shift from silo-based working to a more integrated, professional, team-based approach that operates across organisational boundaries, working with other healthcare professionals and the patient at the centre of it all. The authors envisage that this fully integrated pharmacy service will improve patient care, reduce harm and increase efficiency using a sustainable model of care. This programme of work aligns to national NHS policy drivers, the ‘Five year forward view’

[1]

, ‘Next steps to the five year forward view’

[2]

, ‘Now or never’ published by the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS)[3]

, the professional leadership body for pharmacists and pharmacy in Great Britain, and their commissioned report — ‘Now more than ever’ — published by The Nuffield Trust[4]

.

Over the past 15 years, the pharmacy profession has primarily evolved in three sectors: community pharmacy, hospital pharmacy and primary care. On the whole, these three sectors have developed independently with little influence from each other.

Hospital pharmacy followed the path of clinical pharmacy, and pharmacists started to move from a supply-based function to a more clinical role. Hepler and Strand defined clinical pharmacy as “the responsible provision of drug therapy for the purpose of achieving definite outcomes that improve a patient’s quality of life”[5]

. The European Society of Clinical Pharmacy considers clinical pharmacy a health speciality, where the clinical pharmacist is responsible for developing and promoting the rational and appropriate use of medicines and services[6]

. Furthermore, Tomlin describes clinical pharmacy as a series of interrelated tasks including: medicines information, medicines reconciliation, screening prescribing, risk management, reviewing biochemistry, pharmacokinetics and biochemistry[7]

.

In 2001, the Audit Commission published ‘A spoonful of sugar’ that coined the term ‘medicines management’ in hospitals, describing a series of tasks to ensure that evidence-based medicine was being practised[8]

. Its definition of medicines management in hospitals encompasses the entirety of how medicines are selected, procured, delivered, prescribed, administered and reviewed to optimise the contribution that medicines make to producing the desired outcomes of patient care. In the past ten years especially, hospital pharmacy has also innovated — utilising the skills of pharmacy technicians and assistants — the medicines management process. Hospital pharmacy has also been quick to capitalise on the opportunities offered by pharmacist prescribing, with many specialist and generalist services being developed[9],[10]

, and is now starting to look at advanced clinical skills training for future roles, including pharmacist practitioners.

Community pharmacy services remain focused on the supply of medicines (dispensing), public health advice, self-care, signposting and the disposal of medicines. However, over the past decade, community pharmacy has started to position itself as a profession that provides clinical services — in addition to its supply-based role — in a community setting. The negotiation of a new contract and the development of the contractual framework that came into place in 2005 has enabled pharmacists to undertake advanced services including: medicines use reviews (MURs), influenza vaccinations, new medicines services, appliance use reviews, stoma appliance customisation and the NHS Urgent Medicines Supply Advanced Service[11]

. The MUR service had the potential for improving patient care through better use of medicines. Although initial uptake was erratic[12],[13]

, there were examples of good practice where individual pharmacists were using these new services to enhance the care they were giving their patients[11],[14]

. Individual pharmacists have also developed bespoke community roles, such as palliative care and opioid dependency clinics[15],[16]

. Today, community pharmacies offer a range of clinical services and these roles are likely to expand in the future[17]

. Moving forward, the NHS England Pharmacy Integration programme is developing services specifications for sustainable community pharmacy services across the country (e.g. emergency supply of medicines, minor ailments, linking to NHS 111 and out-of-hours and care homes)[18]

.

Primary care pharmacy started with supporting general medical practices with medicines management and was often specifically driven by a need to reduce medicines-related costs. In the early 1990s, GP practices started to employ practice pharmacists to support medicines management; The Village Green Surgery in north-east England was one of the first practices to do this and their pharmacist supported formulary development, clinical protocols and pathways involving medicines, while also providing patient-facing care. The primary care pharmacy role has grown organically, with a number of differing models emerging over time. There are now several primary care pharmacist models ranging from pharmacists employed by, or even partners in, individual practices, to clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) and acute trusts being the main employer. Pharmacists undertake extensive tasks from medication review to disease-specific interventions, with evidence of improvement in care[19]

. Recently, NHS England commissioned a national programme to support the deployment of pharmacists into general practices[20]

.

Development of the integrated pharmacy team

Northumberland was chosen as one of the national vanguard sites in early 2015, in response to the Five year forward view initiative as a ‘Primary and Acute Care System’ (PACS)[1]

. A PACS system links general practice, hospital, community and mental health services in order to improve the physical, mental, social health and wellbeing of its local population. The Northumberland PACS focused particularly on service integration and examined new potential workforce models, including pharmacy, in order to come up with solutions to address the needs of its population and potential workforce shortages. The lead partners in the Northumberland Vanguard are: Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, NHS Northumberland CCG and Northumberland County Council.

The Northumberland Vanguard model of care provided the impetus to think differently about how pharmacists and pharmacy technicians could work across the three sectors of community, hospital and primary care. The purpose of the vanguard programme was to generate new clinical models to improve patient care and outcomes while reducing cost, accident and emergency attendances, and hospital admissions and readmissions[21]

. All vanguard interventions were required to realise one or more of those indicators. Prior to the vanguard, clinical pharmacy services were provided by a range of providers in a variety of settings: in acute and community hospitals; a small CCG-commissioned service for hospital pharmacists and technicians to work in care homes; in community pharmacy; and in general practice (pharmacists and technicians). There were also commissioning pharmacists working at the CCG who did not provide clinical services.

The first step to a more integrated service was to ensure that newly appointed pharmacists and technicians were working in both hospital and primary care settings. Job plans were also changed to allow existing hospital teams to work in primary care and for primary care-based teams to start working with acute hospital teams. Teams were asked to ‘think across the system’ and not in silos, as had been the case previously.

Primary care pharmacy is most often based around the general medical practice, with each practice receiving a quota of pharmacy time. The Northumberland Vanguard approach was to adopt a community nursing model, where the pharmacy teams are based in geographical hubs serving a patient population of 30,000 to 40,000 people (registered to four to six general medical practices). The first ‘hub’ was set up in Blyth, a town in south-east Northumberland with a population of around 38,000, where this new team’s potential to provide clinical services to patients was tested. The team was co-located with other healthcare professionals (i.e. community nursing, general medical practitioners, social care), noting that the community services team were part of the Trust’s clinical portfolio, and managerial relationships were already strong with a good understanding of what the community team could offer. Initial work by the new pharmacy team focused on building good relationships with existing primary care and social care teams, as well as developing links with community pharmacy and local community hospitals.

As with any new service, particularly when provided at some scale, there was a risk of destabilising the local hospital pharmacy team. Two strategies were used to mitigate against this; first, to create integrated pharmacist and technician roles as described and, second, to develop a foundation pharmacist programme for newly qualified pharmacists whose availability in numbers was not constrained by workforce pressures.

The foundation training programme allows newly qualified pharmacists to develop clinical skills in hospital and general practice, and within three years will lead to the creation of a new clinical pharmacist prescribing workforce. Pharmacists spent blocks of time in general practice and hospital, learning clinical and consultation skills. This was supported by a training programme and mentoring/support from senior pharmacists and general practitioners. The first year of the programme has been evaluated by all key stakeholders (general practices, managers), as well as the foundation pharmacists[22]

. The key findings of this evaluation demonstrated that pharmacists were able to successfully develop their foundation practice while rotating across care settings. Social media was a key component for developing a professional network and informed the boundaries of practice. It is envisaged that these pharmacists will develop quickly into advanced generalists supporting patients with complex medicines needs.

The Northumberland Vanguard pharmacy service has spread from Blyth to three other hubs, with each hub being led by senior clinical pharmacists, specialist pharmacists and technicians. Importantly, each team is part of the wider enhanced care team at each hub: community nursing, social care and general practice. The teams work across traditional organisational barriers, have access to clinical systems from primary, secondary and social care, and provide seamless care for patients. A directory of services ensures that all pharmacist and pharmacy contact details are available to the wider team, enabling enhanced conversations about patients.

The team collects information on every intervention made to each patient using a specially constructed database. This has allowed the models to be tested against the vanguard metrics and key performance indicators, supporting service development and ensuring sustainability.

Development of the integrated pharmacy pathway

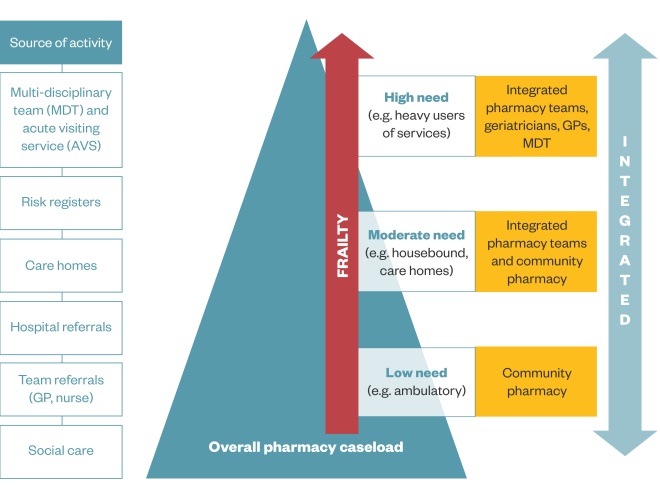

For many years, pharmacy has developed in a fragmented way, with assumptions being made about the effectiveness of service provision. A truly patient-centred approach would start with considering the needs and wishes of the patient. Most patients can manage their medicines on a day-to-day basis, and only occasionally need support. For a variety of reasons (e.g. frailty, learning disabilities) there will be a cohort of patients who have a greater need for medicines support. The Northumberland Vanguard model (see Figure 1) stratifies patients from low to high need for support with medicines, and within that model there is a role for all the previously fragmented pharmacy services to work differently together to support and clinically manage patients. It was the intention of this programme to create a truly integrated team that involved being located across care settings and professionals (e.g. community nurses, GPs).

Patients with a lower need for medicines support in this model are those on one or more regular medicines but are generally healthy, ambulatory, manage their medicines well and are likely to stay that way for many years. Patients with moderate needs include those who have polypharmacy (four or more regular medicines), are moderately frail and have more than one medical condition; hence, could potentially struggle with their medicines. These patients are often hidden from services and may rapidly deteriorate because of a sudden change in their circumstances (e.g. death of a spouse). Those in highest need of support with medicines are usually heavy users of services and have multiple professional contacts. They will usually be on many medicines and quite often medicines that are unsafe, inappropriate or unnecessary, with many being frail, in care homes and/or nearing the final years of life[23]

.

Figure 1: The Northumberland Vanguard Model: stratifying patients according to need

The Northumberland model recognises the role of pharmacy professionals across the system and across organisations

Having stratified patients according to support needed with medicines, a clinical model to meet those needs was developed. An approach using the Institute for Healthcare Improvement model for improvement has been adopted to help develop and implement the range of clinical pharmacy services necessary to support patients with varying medicines needs[24]

. The main aim has been to enhance care with medicines through the best use of the wider pharmacy team, which is integrated with the wider health and social care team. As Figure 1 indicates, the model has community pharmacy supporting the majority of patients who are ambulatory and without complex needs; as complexity increases, the Vanguard team provides greater support/input. In time, as community pharmacists become more confident in dealing with more complex cases, they will pick up a larger caseload. The Vanguard team is there to provide advice and support as required.

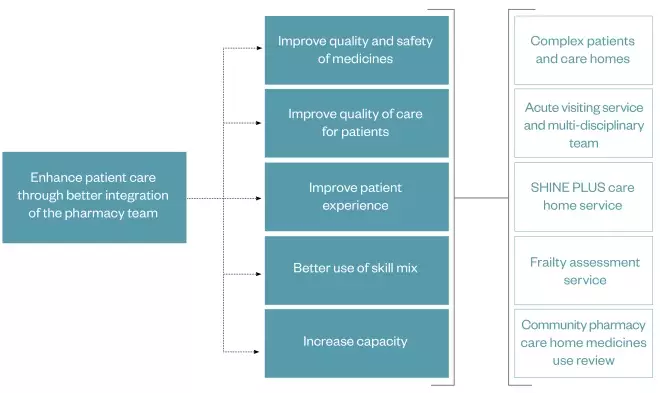

The drivers for change are to improve quality and safety with medicines; improve quality of care and patient experience; use the best skill mix; and increase capacity in the system (see Figure 2). Five key areas of work have been developed: medicines review and optimisation for patients with complex medicines needs; supporting very complex patients through multidisciplinary team (MDT) work; rapid medicines review for care home residents; supporting the frailty assessment service based in the acute Trust; and developing new care models with community pharmacy (see Figure 2).

The team has taken an evidence-based approach to medicines optimisation; clinical interventions are based on guidance from The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (care homes, multimorbidity), NHS Scotland (polypharmacy), national programmes for shared decision making and local initiatives[23],[25],[26],[27],[28]

.

Figure 2: Integrated pharmacy service: drivers for care

There is a range of drivers that come together to enhance patient care

Integrating within the health and social care team

Northumberland has a highly integrated health and social care system and the Vanguard programme allowed pharmacy to better integrate into this system. It is essential to note that, while a focus of this article is on the integration of all sectors of pharmacy within a team-based approach, the real success of the new model has been how the wider healthcare team has responded to and supported pharmacy integration within it (i.e. GPs, consultants, nursing, social care and community services). It was quickly recognised that to get the best from an integrated pharmacy team, the team itself had to work in a coordinated way with all the other healthcare professionals. The development of good relationships with the wider team was a priority when the new teams became hub-based; these new working relationships were an essential precursor to identifying and changing the way that care is provided to patients. Examples of new ways of working resulting from this more integrated model include the following:

- As part of the Northumberland Vanguard programme, it is envisaged that 86% of general practices will be using a single clinical system; this can be accessed by the wider enhanced care team, including pharmacy, and from several sites. Hospital pharmacists can now have read/write access to GP clinical systems, ensuring that changes to medicines can be recorded accurately in real time at the time of patient discharge, negating some of the reliance on existing systems of hospital discharge communication;

- With a better understanding of the whole health and social care system, patients can now be transitioned between settings more effectively in the knowledge that their care will be picked up by another member of the same extended team. Patients can also now be more effectively referred by social services teams to members of the associated and local healthcare team for appropriate support and/or intervention.

- An Acute Visiting Support Service has been developed where patients needing a home visit can be sent the most appropriate practitioner, including a pharmacist rather than all patients having to be seen by a GP;

- The MDT can now proactively find, assess and plan for patients who may need enhanced support. As part of this team, the pharmacy team adds patients with medicines-related issues to their caseload. This allows for better working with patients who now get contact from the most appropriate healthcare professional according to their needs;

- Clinical follow-up and handover when patients leave hospital has improved. Patients who are identified as high risk can now be referred for follow-up after discharge by the same team that is discharging them. Furthermore, rather than delaying a patient’s discharge with often important, but not urgent, changes to medicine therapy (e.g. increased dose of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor), the team can refer the patients to have these changes undertaken at home, thereby prompting immediate discharge and improving hospital flow;

- Many patients have memory problems or a confirmed diagnosis of dementia. It can provide comfort and reassurance to them and their carers that they can often see the same healthcare professionals at various stages of their care pathway. As part of the integrated vanguard model, patients are often encountered on admission to a hospital, supported through acute admission and rehabilitation within the community hospital setting, and are then supported with monitoring after discharge. Furthermore, a new initiative linked to a dementia specialist nurse in order to identify and provide MDT reviews for this high-risk group of patients. This will allow involvement in complex medication reviews and the assessment of various aspects of their therapy (e.g. compliance);

- Residents in care homes are stratified into high, moderate and low need for medicines support. High-need residents are supported through MDT working. A consultant-led geriatrician care home service proactively reviews high-risk older patients. The service is supported by community matrons, care home nurses and the pharmacy team. This integrated approach has ensured the most vulnerable patients are seen in a timely manner. Those patients with moderate needs are usually seen by the pharmacy technician, who has the option to escalate care to the pharmacist or the MDT;

- Every care home in Northumberland is linked to a community pharmacy, which is responsible for the supply of medicines to that care home. Despite some pockets of good practice, community pharmacists do not routinely undertake medication use reviews or any other sort of review of medicines. Furthermore, there are no active strategies to reduce medicines waste from care homes. This is mainly because of the way community pharmacy is funded (dispensing) and barriers faced by community pharmacists to undertaking additional clinical services (pharmacist needs to be on site for medicines to be dispensed or sold; permissions are needed for domiciliary visits; MUR payments do not cover care homes). The model allows community pharmacists to undertake medication reviews for the care home residents they currently dispense for. They are supported clinically and can escalate care to the Vanguard team for more complex patients (see Figure 1);

- Traditionally, care home medicines reviews are undertaken on a home-by-home basis where a care home may not be revisited very frequently (resources dependent). The care model aims to see every new resident for medicines review and every newly discharged resident for technician follow-up (Northumberland NHS SHINE PLUS). This ensures rapid follow-up and support for residents and care home staff.

These, among other initiatives, have helped demonstrate the value of being included as part of the MDT across primary and secondary care settings, which enable patients to get maximal benefit from their medicines while maintaining the highest levels of safety. Having described the model, the final sections of this article focus on the impact and effectiveness of the programme.

Data and metrics

Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians receive patient referrals into their caseload from several sources: hospital teams, GPs, community nursing, social care, voluntary services and hub-based MDT meetings. The team collect data for each patient seen using a specially constructed database. The data are analysed and presented to NHS England.

Since July 2016, the integrated pharmacy team caseload has included 2,445 patients through their caseload across three clinical hubs. Patients are seen on average three times, with 18.7% of patients remaining on the team’s caseload on a long-term basis owing to their complexity. The team has made 5,124 interventions, with the main intervention being deprescribing; a total of 1,001 medicines have been stopped because of safety concerns, inappropriate prescribing or there was no clinical indication. In 79% of cases, the patient, family or carer were fully involved in decisions about their medicines. The SHINE PLUS care home service reviewed 96% of all new or discharged care home residents [Unpublished data].

RIO scores were used to measure impact of interventions. RIO1 meant no impact on admission or readmission; RIO2 was given to interventions that potentially prevented admission or readmission; and RIO3 was given to interventions where an admission was likely to have been avoided. The team made 1,445 RIO2 and RIO3 interventions (28.2% of all admissions), of which 63 were RIO3. It is estimated that since July 2016, we have prevented 223 admissions to hospital [Unpublished data].

The main metrics for savings were from medicines optimisation (medicines stopped and changed) and admissions avoided. Since July 2016, the estimated savings are £900,223. Strategies to manage waste in care homes have saved a further £33,000 over this period [unpublished data].

Box: Case study

A female resident from a care home in west Northumberland was taken to the emergency care hospital following a seizure.

The frailty assessment team and Vanguard pharmacist reviewed the patient in the emergency department. A decision was made to increase the patient’s anti-epileptic medication. Rather than admit the patient, the pharmacist discussed the case with the Vanguard pharmacist in the west hub, who arranged for the dose increase and worked with the GP and community pharmacists to get the medication to the care home. The patient was taken back to the care home from the emergency department.

If the patient had been admitted, it is likely they would have spent several days on the ward.

The future of the Northumberland integrated model

The service continues to evolve as the full benefits of the integrated model are tested, understood and developed. All the developments described are currently being scaled or otherwise further evaluated for sustainability.

Although the PACS framework and funding promoted a common focus on managing people with complex health needs in the community with less reliance on hospital admissions, this collective goal already existed among the health and social care partners in Northumberland. The integrated pharmacy working model developed from previous successes working in care homes and general practices and a vision to optimise medicines wherever patients present.

Integrated working does pose challenges for training and workforce development. Mobilising teams outside of the sector had the potential for missed learning opportunities within secondary care. Recognising that the team are developing to meet future service needs is important to this and support from the senior pharmacy team to balance the needs of all sectors is important. The perceived uncertainty of whether working within an integrated team will have a negative impact on future career opportunities is hopefully dispelled, but organisations looking to replicate should recognise the benefits from integrated working for all job roles and plan accordingly.

Interventional data and metrics have supported roll-out of the integrated team, but through positioning a pharmacy team within a wider service it is difficult to isolate single-service contributions to significant outcomes. Given the potential for subjectivity within the RIO scoring system, ‘possible’ admissions avoided can be viewed with scepticism.

In general practice, although skill mixing is regularly used with practice nurses, healthcare assistants and, more recently, the increased use of pharmacists, prior to this most decisions were made by the GP independently as their role demanded. As a result, inter-professional differences with some GPs can still be a barrier where the relationships have not yet been developed. However, the solution is to demonstrate that the skills within the integrated pharmacy team complement GPs and the primary care workforce, which ultimately leads to better care for patients.

As the service expands in scale and scope, so will the opportunities to do more by skill mixing within the pharmacy team, making full use of the available and future pharmacy technical workforce. The Vanguard pharmacy team already utilises the skills of the pharmacy technicians who work within it, but the opportunities to do more and, at scale, appear boundless.

Financial and conflicts of interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. No writing assistance was used in the production of this manuscript.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] NHS England, Care Quality Commission, Health Education England, Monitor, Public Health England, Trust Development Authority (2014). Five year forward view. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf (accessed May 2018)

[2] NHS England (2017). NHS ‘Next steps on the NHS five year forward view’. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/NEXT-STEPS-ON-THE-NHS-FIVE-YEAR-FORWARD-VIEW.pdf (accessed May 2018)

[3] Smith J, Picton C & Dayan M, on behalf of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (2013). Now or never: shaping pharmacy for the future. Available at: https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Publications/Now%20or%20Never%20-%20Report.pdf (accessed May 2018)

[4] Nuffield Trust (2014). Now more than ever: why pharmacy needs to act. Available at: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/files/2017-01/now-more-than-ever-web-final.pdf (accessed May 2018)

[5] Hepler CD & Strand LM. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm 1990;47(3):533–543. PMID: 2316538

[6] Jorgensen F. Clinical pharmacy and pharmaceutical care — is there a difference? EJHP 2009;15(6):11–12.

[7] Tomlin M. A strategy for clinical pharmacy development. Eur J Hosp Pharm Sci 2013;20:50–53. doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2012-000134

[8] The Audit Commission (2001). A spoonful of sugar. Available at: http://www.eprescribingtoolkit.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/nrspoonfulsugar1.pdf (accessed May 2018)

[9] Baqir W, Crehan O, Murray R et al. Pharmacist prescribing within a UK NHS hospital trust: nature and extent of prescribing, and prevalence of errors. Eur J Hosp Pharm Sci 2014;22(2):79–82. doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2014-000486

[10] Baqir W, Miller D & Richardson G. A brief history of pharmacist prescribing in the UK. Eur J Hosp Pharm Sci 2012;19(5):487–488. doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2012-000189

[11] Richardson E & Pollock AM. Community pharmacy: moving from dispensing to diagnosis and treatment. BMJ 2010;340:c2298. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2298

[12] Blenkinsopp A, Celino G, Bond C & Inch J. Medicines use reviews: The first year of a new community pharmacy service. Pharmaceutical Journal 2009;278(7440):218–223.

[13] Bradley F, Wagner AC, Elvey R et al. Determinants of the uptake of medicines use reviews (MURs) by community pharmacies in England: a multi-method study. Health Policy 2008;88(2–3):258–268. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.03.013

[14] Portlock J, Holden M & Patel S. A community pharmacy asthma MUR project in Hampshire and the Isle of Wight. Pharmaceutical Journal 2009;282(7537):109–112.

[15] Ives TJ & Stults CC. Pharmacy practice in a chemical-dependency treatment center. Am J Hosp Pharm 1990;47(5):1080–1083. PMID: 2337098

[16] Todd A, Husband A, Andrew I et al. Inappropriate prescribing of preventative medication in patients with life-limiting illness: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2017;7(2):113–121. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-000941

[17] NHS England (2016). Independent Review of Community Pharmacy Clinical Services. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/primary-care/pharmacy/ind-review-cpcs/ (accessed May 2018)

[18] NHS England (2017). Pharmacy Integration Fund. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/primary-care/pharmacy/integration-fund/ (accessed May 2018)

[19] Tan EC, Stewart K, Elliott RA & George J. Pharmacist services provided in general practice clinics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Social Adm Pharm 2014;10(4):608–622. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2013.08.006

[20] NHS England. Pharmacists in general practice. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/primary-care/pharmacy/clinical-pharmacists/ (accessed May 2018)

[21] NHS England (2016). New care models: Vanguards — developing a blueprint for the future of NHS and care services. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/new_care_models.pdf (accessed May 2018)

[22] Rathbone A, Baqir W & Campbell D. The Foundation Pharmacist Project: developing new models of integrated pharmaceutical care. IJPP 2017;In Press.

[23] Baqir W, Barrett S, Desai N et al. A clinico-ethical framework for multidisciplinary review of medication in nursing homes. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2014;3(1):pii.u203261.w2538–u203261.w2538. doi: 10.1136/bmjquality.u203261.w2538

[24] Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Model for Improvement. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/HowtoImprove/default.aspx (accessed May 2018)

[25] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2014). Managing Medicines in Care Homes. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/sc1 (accessed May 2018)

[26] Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A & Edwards A. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS: lessons from the MAGIC programme. BMJ 2017;357:j1744. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1744

[27] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2016). Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng56 (accessed May 2018).

[28] NHS Scotland (2015). Polypharmacy Guidance. Available at: http://www.sign.ac.uk/assets/polypharmacy_guidance.pdf (accessed May 2018)