Source: MedSci / Alamy Stock Photo

Key points:

Pharmacy-based dry blood spot testing for blood-borne viruses:

- Can be delivered by pharmacists as a routine service after a brief training intervention;

- Is accessible to individuals with a diverse range of risk factors;

- Is accessed by people who inject drugs who are not engaged with community drug support services and who are less likely to have been tested before;

- Can identify undiagnosed cases of hepatitis C;

- Can re-engage known cases of hepatitis C who have been lost to specialist follow-up;

- Can be integrated with hepatology services to deliver prompt and convenient specialist care for positive cases.

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) affects more than 200,000 people in the UK and accounts for an increasing burden of liver cirrhosis, cancer and mortality[1]

. In recent years there have been dramatic advances in HCV treatment; the new drug regimens are shorter, better tolerated and, since more than 90% of treated individuals achieve cure, they have the potential to significantly reduce global HCV prevalence[2],[3]

. However, challenges in the provision of HCV care remain, with the most pressing being the high proportion of undiagnosed infections[1],[4]

. More than 90% of new diagnoses of HCV in the UK are in people with a current or previous history of injecting drug use and, therefore, the majority of undiagnosed cases are likely to be hidden within this population[1]

. Barriers between this group and HCV care services are well described and include both specific challenges (e.g. difficult venepuncture[5]

) and systemic problems (e.g. stigmatisation and discrimination by healthcare providers[6]

, variable and inadequate testing service provision[7]

and complex, inflexible healthcare services[5]

). Targeted case-finding initiatives for HCV have been undertaken in a range of outpatient institutions and they have been effective at increasing testing activity, identifying previously undiagnosed cases and may increase treatment uptake[8],[9]

. They are also cost-effective and likely to become more so with new treatment regimes[10],[11],[12]

.

Despite challenges, including the need for anonymity from other pharmacy clients and organisational resistance[13]

, community pharmacies are a valued resource for needle exchange[14]

and harm reduction advice for people who inject drugs (PWID), and have a positive impact on risk behaviours (e.g. increased use of clean syringes)[15]

. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), England’s health technology assessment body, recommends that community pharmacies provide these services in the UK, and specifically cater for younger PWID and those injecting body-enhancing substances — two groups who may not access services in conventional drug support settings[16]

. The provision of community testing services for blood-borne viruses (BBV; e.g. HCV) is a logical next step in community pharmacy service development and may have value in reaching at-risk individuals in rural areas, where a lack of other local services and geographical barriers prevent testing[6]

.

The Isle of Wight (IOW) is a rural, geographically isolated population off the south coast of the UK. In 2010, local pharmacists participated in a nationwide pilot of BBV and syphilis testing in community pharmacies that was supported by the Hepatitis C Trust[17]

. Nine pharmacies on the IOW took part and performed more than 100 tests, which represented the majority conducted nationally. Seven cases of RNA-positive HCV were identified, although it is not known whether they were new or existing cases. These cases were first referred to the local sexual health service and later referred to HCV services on the UK mainland (based in Southampton). Unfortunately, despite the success of the case finding, only one patient ever saw a specialist, no one received treatment and the service did not receive further funding[17]

.

Based on a comparison between clinical records and Health Protection Agency (now part of Public Health England, an executive agency of the Department of Health in the UK) prevalence estimates, up to 200 cases of HCV remain undiagnosed on the IOW. Of the known cases, only a third are actively engaged in specialist care[18]

. When this is considered alongside the changing treatment landscape for HCV, it is clear that a new service is needed that integrates, through a robust referral pathway, effective pharmacy based case finding with locally available specialist care.

Accordingly, this is a report of a nine-month pilot (September 2014 to May 2015) of a pharmacy-based testing service for HCV, other BBV and syphilis. Where necessary, a novel automated referral pathway to hepatology specialists on the UK mainland and a point-of-diagnosis pharmacy-based specialist consultation were incorporated.

Method

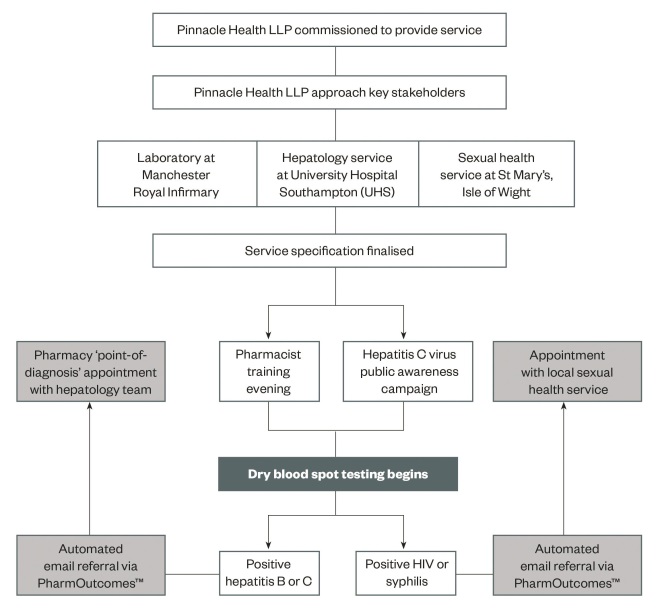

Service development and implementation

Pinnacle Health LLP, an agency specialising in developing health services, was commissioned by the IOW local authority to design and implement the service; the step-by-step service guide is available in the supplementary information (see online supplementary information, ‘Appendix 1’). All 31 community pharmacies on the IOW were given the opportunity to participate in the service. In total, 22 community pharmacies enrolled in the initiative, which provided at least one testing pharmacy within every town on the IOW. In general, participating pharmacies had previously been engaged in local service development, had an experienced full-time pharmacist, and had expertise in the delivery of needle exchange and opiate substitution therapy.

A four-hour training event was held for pharmacists on pre-test and post-test counselling, as well as the practical aspects of conducting a dry blood spot (DBS) test (see online supplementary information ‘Appendix 1’ for more detail). The event also featured sessions by allied professionals on the clinical aspects of HCV, hepatitis B virus (HBV), syphilis and HIV. At the outset of the initiative, pharmacies not offering the test were visited to ensure they were equipped with the necessary information to advise and signpost individuals to a testing site.

Pharmacists were trained to offer testing to anyone attending for needle exchange and opiate substitution therapy. In addition, an island-wide advertising campaign, entitled “Are you one of the missing 200?”, was undertaken by pharmacy and local hospital services (see ‘Supplementary Figure 1: A bus side advertisement’). This campaign incorporated radio interviews, bus side banners and local press editorials, and aimed to highlight the range of risk factors for HCV and encourage self-referral for pharmacy-based testing.

Each patient underwent pre-test counselling with a trained pharmacist. This included a description of the test procedure, follow-up arrangements and verbal consent for onward referral. The DBS sample (Abbott Architect) was taken by the pharmacist and sent to the Manchester Royal Infirmary (UK) where a positive test for HCV antibody prompted in-house polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for RNA and genotyping. Any individuals testing positive for HCV RNA or HBV surface antigen received an automatic secure email referral via PharmOutcomesâ„¢ software to the local hepatology service. Follow-up appointments were typically seven days later (see ‘Figure 1: The design and implementation’).

In the event of a positive test for HBV surface antigen or HCV RNA, a member of the hepatology team attended the pharmacy for a point-of-diagnosis consultation with the patient and testing pharmacist. This included further blood tests, clinical examination and, where appropriate, referral for liver imaging and HCV treatment. Positive tests for HIV and syphilis were referred to the local sexual health service (see ‘Figure 1: The design and implementation’).

Figure 1: Service design and implementation

The design and implementation of a pharmacy dry blood spot testing service for blood-borne viruses and syphilis on the Isle of Wight

Funding

The IOW local authority funded the service, including the pharmacist’s time to collect samples, DBS kits and the testing of samples at Manchester Royal Infirmary. Each pharmacy received £30 per test, which was split into £15 for sample collection and the entry of results into PharmOutcomes, and £15 for the delivery of the results to the client. The hepatology team were funded jointly by a National Institute of Health research (NIHR) fellowship and a GILEAD LTD fellowship. Funding for a specialist hepatitis nurse based at St Mary’s Hospital on the IOW was secured from the local clinical commissioning group. This specialist role has outreach capacity built into the service specification and job plan and, therefore, gives sustainability to the integrated service in its current form.

Data analysis

PharmOutcomes software routinely collected data on those individuals undertaking a test at the community pharmacy. This was compared with individuals tested at the island recovery integrated service (IRIS) across the same time period. Data analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel (2011) and P values for significance were calculated using the GraphPad QuickCalcs[19]

.

Results

Service outcomes

Between September 2014 and May 2015, a total of 88 individuals underwent pharmacy-based testing. A range of testing activity was documented at the 22 participating pharmacies; three pharmacies accounted for 55% of tests and five undertook no testing at all.

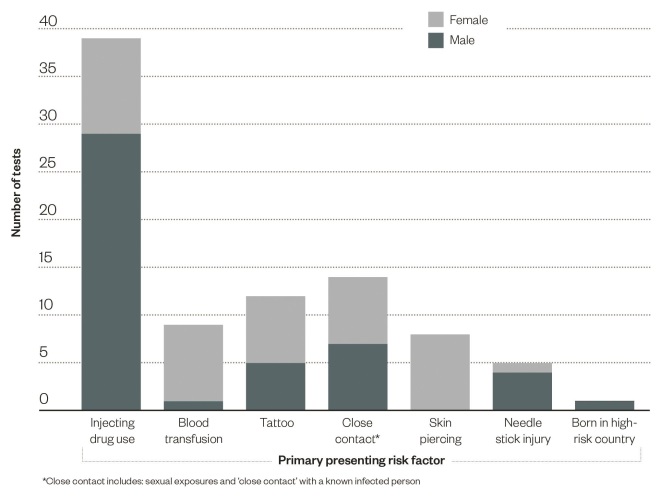

Of those patients tested, 54% were male and the average age was 40 years (range 22–71 years). A range of indications for testing were also present, these are summarised in ‘Figure 2: The disclosed primary risk factor for persons undergoing a community pharmacy blood-borne virus and syphilis test’.

Figure 2: Primary risk factors disclosed during testing

The disclosed primary risk factor for persons undergoing a community pharmacy blood-borne virus and syphilis test

There was heterogeneity in the primary presenting risk factor for testing between males and females. A significantly greater proportion of males disclosed a history of injecting drug use (62%, P <0.01), whereas a significantly greater proportion of females reported a historical blood transfusion (20%, P =0.01) and a skin piercing in a high-risk environment (20%, P <0.01) (see figure 2).

Overall, 16 (18%) of tested individuals presented as a result of the publicity campaign, with the remainder of patients directly recruited by pharmacists. Of those responding to the public health campaign, the primary risk factor was very varied: five patients reported having a skin piercing in a high risk environment, three patients (19%) reported a tattoo in a high risk environment and three patients (19%) disclosed close contact with a person known to be infected with a BBV. Just two patients (13%) reported injecting drug use. This was significantly different from those recruited directly by the testing pharmacist, 36 (50%, P <0.01) of whom reported injecting drug use.

Overall, injecting drug use was the most common reported risk factor. These individuals were significantly more likely to have a history of incarceration (55%, P <0.01) and to have had a test in the past three years (62%, P <0.01), compared with those reporting an alternative risk factor (Table 1-A). In total, 17 (44%) of patients who reported previous injecting drug use were not engaged at the IRIS centre. Compared with those PWID who did attend the centre, they were significantly less likely to report a test in the past three years (41% vs 77%, P =0.04) (Table 1-B).

| Table 1: Demographics of individuals tested for blood-borne viruses and syphilis at community pharmacies on the Isle of Wight during the nine-month pilot period (September 2014 to May 2015) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | |||||||

| Pharmacy non-PWID (n=49) | Pharmacy PWID (n=39) | P value | Pharmacy PWID IRIS client (n=22) | Pharmacy PWID non-IRIS client (n=17) | P value | Pharmacy all tests (n=88) | IRIS centre (n=34) | P value | |

| Age (years) | 40 | 40 | 1 | 40 | 40 | 1 | 40 | 35 | 0.1 |

| Previous test in past three years (%) | 8(16) | 24(62) | <0.01 | 17(77) | 7(41) | 0.04 | 32(36) | 19(56) | 0.07 |

| Prison history (n*) | 3(47) | 17(31) | <0.01 | 10(19) | 7(12) | 1 | 21(78) | 12(34) | 0.26 |

| IDU main RF (%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 36(41) | 29(85) | <0.01 |

| Positive HCV RNA (%) | 1(2) | 5(13) | 0.08 | 2(9) | 3(18) | 0.63 | 6(7) | 3(9) | 0.7 |

| Positive patients seen by specialist (%) | 1(100) | 5(100) | 1 | 2(100) | 3(100) | 1 | 6(100) | 0(0) | <0.01 |

A) Comparing pharmacy-tested individuals with and without a history of injecting drugs use. B) Comparing pharmacy-tested individuals with a history of injecting drug use who are and are not clients at the island recovery integrated service (IRIS) drug support centre. C) All pharmacy-tested individuals compared with those tested at the IRIS drug support centre during the same period.

HCV: Hepatitis C virus; IDU: Injecting drug use; RF: Risk factor; PWID: people who inject drugs, IRIS: Island integrated recovery service

*Ten pharmacy clients declined to give details of previous incarceration | |||||||||

Overall, 34 tests were undertaken at the IRIS centre during the same nine-month period. These individuals were younger (35 years, P =0.01), more likely to have had a previous test (56%, P =0.07) and a larger proportion reported injecting drug use as their primary risk factor (85%, P <0.01) (Table 1-C).

A similar proportion of pharmacy and IRIS centre tests were positive for HCV (7% and 9%, respectively), with the greatest proportion of positive pharmacy tests being in PWID not engaged at the IRIS centre (Table 1-B). All individuals from the IRIS centre and community pharmacies had genotype 3 HCV (the most treatment-resistant and most aggressive type of HCV), with the exception of two cases of genotype 1 virus (the most common virus form) diagnosed at the same pharmacy. These two patients were in a sexual relationship and admitted sharing drug injection paraphernalia.

Patients positively identified in community pharmacies attended a point-of-diagnosis consultation with the testing pharmacist and hepatology specialist from the UK mainland. All patients had baseline investigations and remain actively engaged in the HCV care pathway, where two patients have now commenced treatment. Of the three patients who tested positive at IRIS, all were appropriately referred but, at the time of acceptance for publication, none have been seen by a hepatology specialist. During the pilot a single positive test for HBV surface antigen was obtained from one patient that went on to be spontaneously clear. No positive cases of HIV or syphilis were identified.

Discussion

This article describes a nine-month integrated HCV care initiative between community pharmacies on the IOW and specialist hepatology services. It is, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, unique in medical and pharmaceutical practice.

The provision of pharmacy-based testing more than trebled the number of tests for HCV undertaken in community open access settings during the pilot period and provides additional capacity for testing in the future. DBS testing for BBV and syphilis avoids the challenges of venepuncture and it was possible for community pharmacists to conduct the procedure as a routine service after a short training intervention[20]

. DBS testing has been successfully implemented in a variety of other community locations in the UK, but we have demonstrated that pharmacies are able to reach patients with more diverse risk factors, who are not engaged with, and are therefore less likely to have been tested at, other services[21],[22],[23]

. This may be because of the inherently non-stigmatising nature of community pharmacies and the co-provision of a range of other services, such as routine prescriptions and needle exchange.

Of the 22 pharmacies enrolled into this service, three conducted the majority of tests, raising questions about whether the delivery of such a service is a realistic prospect in all pharmacies. Testing activity did correlate closely with needle exchange activity, but may also reflect the experience of the pharmacist, engagement with testing training sessions, staff turnover and the availability of facilities (e.g. a private treatment room). Accordingly, future service provision should target ‘flagship’ pharmacies with enthusiastic, experienced staff and adequate resources. In non-testing pharmacies, a focus should be placed on raising awareness about who is at risk from BBV and where they can be signposted for testing.

Other case finding initiatives for HCV have been successful in identifying large numbers of new or previously ‘lost to follow-up’ cases of HCV, however, engaging patients with specialist follow-up has proved challenging[22],[24]

. The referral software PharmOutcomes was successful in automatically and reliably sending a secure email to the hepatology team, notifying them of the positive result along with a date and time for the pharmacy-based consultation. In reality, however, the team were not always able to attend on the nominated day and so liaised directly with the pharmacy to plan an alternative appointment. This was easily achieved in all positive cases and highlighted to the medical team how readily pharmacists can communicate with and access positively-identified patients. The majority of new cases identified in this pilot were PWID, a group who are particularly difficult to engage with hospital services[4],[6]

. Their apparent willingness to attend a pharmacy for a point-of-diagnosis consultation was striking and highlights the potential utility of local pharmacies as venues for community-based HCV treatment in the future. Such a service could perhaps be integrated with other pharmacy services, including opiate replacement therapy and needle exchange.

Moving forward, this integrated service can be implemented more widely. On the IOW it identified and engaged new cases of HCV, while in more urban and ethnically diverse communities it could have value in identifying individuals with HIV and HBV. However, to introduce the service elsewhere there will need to be local ‘buy in’ and flexibility from hepatology and sexual health services, as well as enthusiasm from the local pharmaceutical committee (LPC). Furthermore, there will need to be provision of adequate financial resources from local healthcare commissioners.

Conclusion

This pilot has demonstrated that pharmacy-based testing for BBV and syphilis is accessible and acceptable to individuals with a wide range of infection risk factors, and can identify previously undiagnosed cases of HCV. The pilot has also shown that pharmacists and hepatologists can work collaboratively to provide readily accessible, community services for patients with HCV and thereby secure patient engagement at the beginning of their care pathway. If implemented more widely, this strategy has the potential to identify, engage and cure patients with HCV across the UK and, therefore, contribute to the wider fight against liver-related morbidity and mortality.

Ryan Buchanan is hepatology registrar, Department of Hepatology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton and hepatology research fellow, Public Health Sciences & Medical Statistics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton. Pembe Hassan-Hicks is pharmacist at Regent Pharmacy, Isle of Wight. Kevin Noble is managing partner, pharmacist at Pinnacle Health LLP, Isle of Wight. Leonie Grellier is consultant gastroenterologist, Department of Gastroenterology, St Mary’s Hospital, Isle of Wight. Julie Parkes is associate professor Public Health, Public Health Sciences & Medical Statistics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton. Salim I Khakoo is professor of hepatology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton. Correspondence to: ryan.buchanan@nhs.net

Financial and conflicts of interest disclosure:

Salim I Khakoo and Ryan Buchanan received funding from Gilead Ltd. Kevin Noble is one of two managing partners in Pinnacle Health LLP who are responsible for the PharmOutcomes system. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. No writing assistance was utilised in the production of this manuscript.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] Public Health England. Hepatitis C in the UK. 2014. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/hepatitis-c-in-the-uk (accessed July 2016).

[2] Webster DP, Klenerman P& Dusheiko GM. Hepatitis C. The Lancet 2015;385(9973):1124–1135. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62401-6

[3] Bennett H, McEwan P, Sugrue D et al. Assessing the long-term impact of treating hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected people who inject drugs in the UK and the relationship between treatment uptake and efficacy on future infections. PLoS One 2015;10(5):e0125846. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125846

[4] McGowan CE & Fried MW. Barriers to hepatitis C treatment. Liver Int 2012;32:151–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02706.x

[5] World Health Organisation. Barriers and facilitators to hepatitis C treatment for people who inject drugs: A qualitative-study. 2012. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/179750/Barriers-and-facilitators-to-hepatitis-C-treatment-for-PWID-A-qualitative-study-June-2012-rev-5.pdf?ua=1 (accessed July 2016).

[6] Harris M & Rhodes T. Hepatitis C treatment access and uptake for people who inject drugs: a review mapping the role of social factors. Harm Reduct J 2013;10:7. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-10-7

[7] Parkes J, Roderick P, Bennett-Lloyd B et al. Variation in hepatitis C services may lead to inequity of heath-care provision: a survey of the organisation and delivery of services in the United Kingdom. BMC Public Health 2006;6(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-3

[8] Aspinall EJ, Doyle JS, Corson S et al. Targeted hepatitis C antibody testing interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol 2015;30(2):115–129. doi: 10.1007/s10654-014-9958-4

[9] Chou R, Cottrell E, Wasson N et al. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection in adults. Comparative effectiveness review No. 69. (Prepared by the Oregon Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2007-10057-I.). AHRQ - Agency Healthc Res Qual. 2012;12(13).

[10] Martin NK, Vickerman P, Miners A et al. Cost–effectiveness of hepatitis C virus antiviral treatment for injection drug user populations. Hepatology 2012;55(1):49–57. doi: 10.1002/hep.24656

[11] Martin NK, Hickman M, Miners A et al. Cost–effectiveness of HCV case-finding for people who inject drugs via dried blood spot testing in specialist addiction services and prisons. BMJ Open 2013;3(8). doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003153

[12] Castelnuovo E, Thompson-Coon J, Pitt M et al. The cost-effectiveness of testing for hepatitis C in former injecting drug users. Health Technol Assess 2006;10(32). doi: 10.3310/hta10320

[13] Hammett TM, Phan S, Gaggin J et al. Pharmacies as providers of expanded health services for people who inject drugs: a review of laws, policies, and barriers in six countries. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14(1):261. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-261

[14] Yang Y, Latkin C, Luan R et al. Reality and feasibility for pharmacy-delivered services for PWID in Xichang, China: Comparisons between pharmacy staff and PWID. Int J Drug Policy 2015;27:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.05.015

[15] Lewis CF, Rivera AV, Crawford ND et al. Pharmacy-randomized intervention delivering HIV prevention services during the syringe sale to people who inject drugs in New York City. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015;153:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.06.006

[16] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Needle & syringe programmes. NICE clinical guideline PH52. 2014. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/PH52 (accessed July 2016).

[17] Hepatitis C Trust. Pharmacy-based Hepatitis testing. 2013. Available at: www.hcvaction.org.uk/sites/default/files/resources/Pharmacy-based%20testing%20for%20hepatitis%20B%20and%20hepatitis%20C%20(hep%20c%20trust).pdf (accessed July 2016).

[18] Health Protection Agency. Hepatitis C in South East Region 2011. Available at: http://www.yhln.org.uk/data/documents/Useful%20Documents%20area/Hepatitis%20C%20in%20the%20UK%20(HPA)%20Annual%20Reprt%202009.pdf (accessed July 2016).

[19] GraphPad QuickCalcs. Available at: www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/ (accessed March 2016).

[20] Craine N, Parry J, O’Toole J et al. Improving blood-borne viral diagnosis; clinical audit of the uptake of dried blood spot testing offered by a substance misuse service.J Viral Hepat 2009;16(3):219–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2008.01061.x

[21] Hickman M, McDonald T, Judd A et al. Increasing the uptake of hepatitis C virus testing among injecting drug users in specialist drug treatment and prison settings by using dried blood spots for diagnostic testing: a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Viral Hepat 2008;15(4):250–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00937.x

[22] Tait JM, Stephens BP, McIntyre PG et al. Dry blood spot testing for hepatitis C in people who injected drugs: reaching the populations other tests cannot reach. Frontline Gastroenterol 2013;4(4):255–262. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2013-100308

[23] McLeod A, Weir A, Aitken C et al. Rise in testing and diagnosis associated with Scotland’s Action Plan on Hepatitis C and introduction of dried blood spot testing. J Epidemiol Community Heal 68(12):1182–1188. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-204451

[24] Cullen BL, Hutchinson SJ, Cameron SO et al. Identifying former injecting drug users infected with hepatitis C: an evaluation of a general practice-based case-finding intervention. J Public Health (Oxf) 2012;34(1):14–23. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdr097

You may also be interested in

Everything you need to know about mpox

Norovirus and strategies for infection control