Introduction

Performance concerns among doctors have been widely studied.[1]

However, little is known about performance concerns among pharmacists.[2]

While the General Medical Council (GMC), the regulatory body for the medical profession, has the power to investigate a doctor whose performance may be “seriously deficient”, until recently the regulatory authority for pharmacy (formerly the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, now the General Pharmaceutical Council [GPhC]) has had no jurisdiction to investigate allegations of “deficient professional performance”. However, recent legislative changes under The Pharmacists and Pharmacy Technicians Order 2007 (Section 60) now allows the pharmacy regulator to investigate performance concerns, and in 2007 fitness-to-practise procedures were introduced.[3]

The function of the fitness-to-practise directorate of the GPhC is to monitor and ensure compliance with the standards of conduct, performance and fitness-to-practise set by the GPhC,[4]

and with obligations imposed on the pharmacy profession by statute. Where a person registered with the GPhC or lawfully conducting a retail pharmacy business fails to comply with those standards and legal obligations, it falls to the fitness-to-practise directorate to take action to enforce those standards and legal obligations.[1]

There is provision for fitness-to-practise procedures to involve performance assessments similar to those currently undertaken by the GMC,[5],[6]

for doctors and include: a test of knowledge; observation of the registrant in practice; examination of records (such as continuing professional development); practitioner interview, and third party interviews. At present this provision is not routinely used.

Most registered pharmacists perform to an acceptable standard but annually approximately 1 per cent come under investigation, often for problems associated with their performance.[7]

Data from the 2009 fitness-to-practise report[7] indicate that almost half of the allegations against pharmacists considered by the investigating committee originated from complaints from members of the public, with the police responsible for 10 per cent and employers and primary care organisations responsible for approximately 7 per cent of allegations. Roughly two-thirds of allegations relate to pharmacists working in the community sector, where most pharmacists (c 70 per cent) in England practise.[8]

Most of the remainder practise in the hospital sector.[8]

Currently, little is known about the identification and management of performance problems in the pharmacy profession. Hospital trusts are likely to have a structured process in place for their employees, as they fall under the NHS knowledge and skills framework (KSF). The KSF is designed to identify the knowledge and skills that individuals need to apply in their post, guide an individual’s development and provide a “fair and objective framework on which to base review and development”.[9]

The performance of employee pharmacists in the community sector is likely to be monitored by the employing organisation. The situation regarding community pharmacy owners and self-employed locum pharmacists is, however, less obvious, due to the absence of a clear management structure. However, there is little information in the public domain about how pharmacy employers in either sector identify or manage performance concerns.

Performance concerns relating to community pharmacists may also be identified and managed by primary care organisations (PCOs), which contract for and commission pharmacy services and monitor compliance with contractual obligations. We do not know, however, whether practices are uniform across all PCOs, or how issues raised and dealt with by PCOs vary, depending on the source or type of concern. No research has yet identified at what point and why a PCO might involve other bodies (eg, the pharmacy regulator) or how many cases are dealt with. Moreover, PCOs are only one of several types of organisation dealing with problems relating to pharmacists’ performance

Support for pharmacists and their employers in relation to performance concerns is available from the National Clinical Assessment Service (NCAS). Established in 2001, the service initially dealt with performance concerns among doctors and dentists, but in April 2009 the organisation’s remit was widened to include pharmacists. The NCAS helps local healthcare managers and practitioners to understand, manage and prevent performance concerns.[10]

They help to clarify the concerns, understand what is leading to them and support their resolution. NCAS aims to get involved early and, offers interventions and shared learning.

To support the NCAS in developing its specific role with pharmacists, it commissioned a study, the overall aim of which was to explore processes for the identification and management of pharmacists’ performance concerns. The work reported here centres on determining how primary care trusts (PCTs) and hospital trusts in England identify and manage different types of performance concerns of pharmacists either commissioned to provide services for them (PCTs) or employed within their organisation (hospital trusts).

Other aspects of the study have been reported elsewhere.[11],[12]

Methods

Based on a review of the literature and semi- structured interviews with community pharmacy stakeholders,[11]

a questionnaire was developed to explore the identification and management of performance concerns. Respondents were asked to rank the most common route by which they became aware of performance concerns from a predefined list. The questionnaire also contained a series of 24 statements relating to aspects of pharmacists’ performance which may be cause for concern. Respondents were asked, using the traffic light system outlined in Panel 1, how they would manage these concerns in (for PCT respondents) community pharmacists providing commissioned services in the PCT locality or (for hospital trust respondents) in hospital pharmacists working in the trust. The traffic light system was adapted from one previously used with GPs in a PCT in England.[13]

The questionnaire also included questions about the use of appraisals for revalidation, which has been published elsewhere.[14]

The questionnaire was piloted with a small number of pharmacists who were working in either PCTs or hospital trusts and minor changes to the wording were made. The study was classified as service evaluation and development by the National Research Ethics Service, so formal ethics committee approval was not required.

Traffic light system

The traffic light system for dealing with performance issues is as follows:

Green — isolated or resolved episode of minor concern, can be dealt with by signposting to appropriate group for learning development and outcomes

Amber — performance giving cause for concern but can be remedied at a local level, such as through a performance advisory group, a local pharmaceutical committee or occupational health services, with advice from external bodies (eg, the National Clinical Assessment Service)

Red — performance is significantly and repeatedly below that which is expected, concerns requiring local investigation that may be addressed with the benefit of advice or assessment from an external organisation (eg, NCAS)

Fitness-to-practice (FtP) issue — performance considered serious enough potentially to call into question the pharmacist’s fitness to practise, refer to regulator

The questionnaire was sent to clinical governance leads in all 152 PCTs in England and to a random sample of clinical governance leads in 50 per cent of acute hospital trusts in England (n=85) in October and November 2009. Two reminders were sent at intervals of four weeks and 10 weeks after the original mailing. Subsequent telephone calls were made to PCTs to try to identify named clinical governance or medicines management leads, who were then sent a further survey. Questionnaires were also sent to chief pharmacists in non-responding acute trusts. Medicines management leads and chief pharmacists were approached following feedback from the earlier mailings suggesting that performance concerns were often delegated to these professionals. Data were analysed using SPSS Version 16 and descriptive statistics are reported. Responses from PCTs and hospital trusts are presented alongside each other to aid comparison. However, due to the small sample size, inferential statistics were not possible.

Results

Sixty-nine PCT and 32 hospital trust questionnaires were completed and returned, giving an overall response rate of 43 per cent and individual response rates of 44 per cent and 33 per cent, respectively.

How are performance concerns identified?

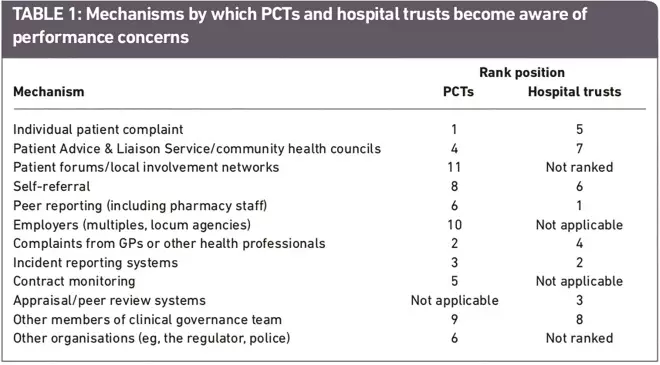

PCT respondents reported that they most commonly become aware of performance concerns about pharmacists through individual patient complaints, complaints from GPs and through incident reporting systems, which were ranked in the top three most often (Table 1). Hospital trust respondents most commonly became aware of performance concerns about pharmacists through peer reporting, incident reporting systems and appraisal or peer review systems, which were ranked in the top three most often.

Table 1. Mechanisms by which PCTs and hospital trusts become aware of performance concerns

How are performance concerns managed?

Behavioural and professional attitudes

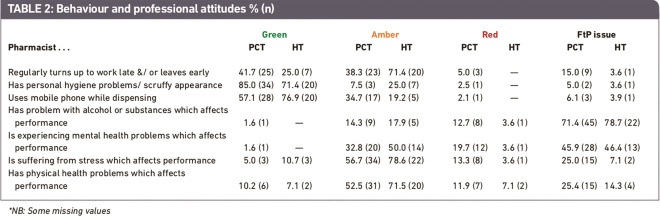

The data in Table 2 suggest that most PCT and hospital respondents regarded issues such as lateness, hygiene problems and use of mobile telephones as relatively minor performance concerns, which could be dealt with at a local level (green). Issues around stress and physical health were also considered best dealt with at a local level, albeit with the involvement of others, for example, a performance advisory group, local pharmaceutical committee, occupational health or advice from an external agency such as the NCAS (amber).

Table 2. Behaviour and professional attitudes % (n)

Pharmacists who were experiencing mental health problems were regarded as requiring a firmer approach but respondents were split as to whether this required local investigation with advice or assessment from an external agency such as the NCAS (amber) or referral to the regulator. Problems with alcohol or other substances, however, were considered to require such referral by the majority of respondents.

These data also suggest that PCT respondents were more likely than their hospital counterparts to refer performance concerns relating to stress and physical health to the regulator.

Communication

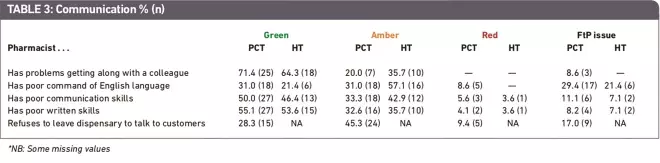

Most PCT and hospital trust respondents regarded all communication issues as concerns that could be dealt with at a local level (green or amber). However, concerns with pharmacists’ poor command of the English language were more likely than other communication issues to be treated as a serious concern and be referred externally. Moreover, a higher proportion of PCT clinical governance leads appeared to regard having problems with the English language as a red or fitness-to-practise issue than hospital clinical governance leads (Table 3).

Table 3. Communication % (n)

Dispensing and advice-giving

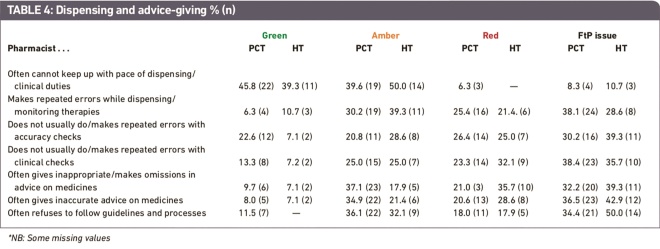

Most PCT and hospital respondents regarded performance issues around dispensing and advice-giving as major concerns, to be managed with the assistance of external organisations or the involvement of regulators. The exception to this was failure to keep up with the pace of dispensing, which was regarded as remediable at a local level (Table 4).

Table 4. Dispensing and advice giving % (n)

There appeared to be a tendency for hospital trust respondents to deal with a number of these performance concerns as red or fitness-to-practise issues than their PCT counterparts.

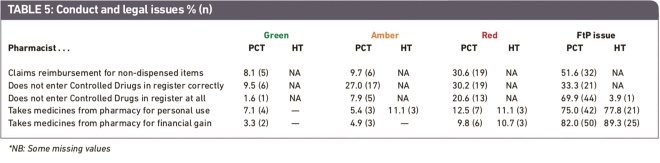

Conduct and legal issues

More than three-quarters of both PCT and hospital trust respondents regarded the taking of medicines from the pharmacy for personal use and particularly for financial gain as being a fitness-to-practise issue which would require external or regulator involvement (Table 5).

Table 5. Conduct and legal issues % (n)

As pilot work with hospital pharmacists had suggested that the remaining three conduct and legal issues were not of relevance to them, hospital respondents were only asked to comment on two of the five concerns in this category. PCT respondents thought that failure to enter Controlled Drugs in the register and claiming reimbursement for non- dispensed items that could only be dealt with through external involvement, possibly including the regulator.

Discussion and conclusions

The findings from these surveys have offered novel and useful insights into how PCTs and hospital trusts view the seriousness of different types of performance concerns among pharmacists working in the community or hospital sector.

There are a number of possible limitations to the study, which must be taken into account when considering the findings. The response rates to the two surveys were under 50 per cent and we cannot therefore know whether the responses provided are generalisable to the wider population of PCTs and hospital trusts in England. The low response rate may be attributable to a number of factors, including a national postal strike that coincided with the first mailing, the length of the questionnaire and the fact that it was not possible to send the questionnaire to named individuals. As a result of the response rates and the relatively low sample sizes it has not been possible to do any comparative statistical analysis of PCT and hospital responses. Notwithstanding these limitations, these data still have value as it is the first time, to our best knowledge, that the processes relating to identifying and managing pharmacists’ performance concerns in England have been studied.

The findings suggest that while certain behavioural issues are likely to be dealt with internally, issues relating to alcohol or substance misuse or mental health problems are more likely to be viewed more seriously and escalated more readily, possibly through referral to the regulator. Although a higher proportion of PCT than hospital trust respondents would deal with physical health problems and issues around stress with the help of external agencies, such as the NCAS, statistical testing of these differences was not possible and the majority of both sets of respondents regarded these issues as internal matters. From the responses to this part of the survey it could be argued that that behavioural performance concerns caused the greatest ambivalence among those responsible for overseeing the management of hospital and community pharmacists’ performance.

Concerns around communication were largely dealt with internally, even in the case of problems with the English language. evidence for whether substandard English language skills cause problems, with potential implications for patient safety, are currently anecdotal. However, research is currently under way to explore the experiences of internationally trained pharmacists and analysis of interviews with EU-trained pharmacists suggest that communication caused anxiety to many and that they struggled with dialects, colloquialisms and differences in terminology and jargon.[15]

Although the registration of pharmacists who qualified outside Europe involves additional training and proof of language skills this requirement is not in place for European pharmacists who enter the register under European equivalence of qualifications legislation.[16]

This leaves the onus for language testing with employers, yet many do not seem to realise this.[17]

The types of performance concerns most likely to be treated as fitness-to-practise issues by both PCT and hospital trust respondents related to alcohol and substance abuse and conduct and legal issues. A high proportion of both sets of respondents also regarded performance concerns related to mental health issues in this way. investigations into the risk factors for referral to the pharmacy regulator’s fitness-to-practise committee[18]

and the characteristics of the first pharmacists referred to the NCAS support these findings.[19]

Although it was not possible to test for statistical differences in the two samples because of the small sample sizes, there was some evidence to suggest that PCT and hospital respondents might respond differently to certain performance concerns. This is perhaps to be expected however, because the roles of PCTs and hospital trusts in relation to pharmacists are greatly different. As the direct employer of a pharmacist a hospital trust is better placed to deal with issues internally and may also become aware of problems at an earlier stage than a PCT. PCTs, as mentioned previously, in most circumstances do not directly employ the community pharmacists who provide services in their locality. There is also evidence from this study to suggest that the route by which PCTs and hospital trusts become aware of performance concerns may vary. This might affect the type of performance concern reported or the stage at which an intervention occurs. This is something that would merit further study. Significant changes to the way in which services are commissioned, most notably the planned decommissioning of PCTs in England in 2013 and the handing over of commissioning responsibilities to GPs is likely to result in significant changes to the way in which performance concerns are identified and managed, and this is a topic that will clearly require further investigation.[20]

To our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind to explore how NHS organisations deal with performance concerns about individual pharmacists. Further research is needed to gain a greater understanding of the processes involved.

Future research in this area should include qualitative explorations with pharmacists themselves to obtain first-hand information about how their own performance concerns have been managed and rectified. Records of referrals to the NCAS, the regulator and other support services could be interrogated to examine risk factors and the processes and outcomes associated with different types of cases.

Finally, researchers should aim to observe the real-life decision-making processes if possible, so that contextual factors can be taken into account.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Clinical Assessment Service. it was undertaken by the authors, all at the university of Manchester, and the views expressed in the publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of NCAS.

Acknowledgements

We thank all those individuals in primary care trusts and hospital trusts who took the time to complete and return the surveys which form the basis for this article.

About the authors

Liz Seston, PhD, is research fellow, Karen Hassell, PhD, is professor of social pharmacy, Sally Jacobs, PhD, is research fellow, Helen Potter, MRPharmS, is a PhD student, Julie Prescott is research associate and Ellen Schafheutle, PhD, MRPharmS is lecturer in law and professionalism in pharmacy, all at the University of Manchester

Correspondence to: Ellen Schafheutle, Centre for Pharmacy Workforce Studies, School of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Manchester, First Floor, Stopford Building, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PT (email ellen.schafheutle@manchester.ac.uk)

References

[1] Cox J, King J, Hutchinson A, McAvoy P. Understanding doctors’ performance. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing; 2006.

[2] Seston EM, Schafheutle EI. A literature review on factors influencing pharmacist performance. London: National Clinical Assessment Service; 2010.

[3] Statutory Instrument. The Pharmacists and Pharmacy Technicians Order 2007. No 289. Available at: www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2007/ 289/contents/made (accessed 29 July 2011).

[4] Standards and quality. General Pharmaceutical Council. Available at: www.pharmacy regulation.org/regulatingpharmacy/ standardsandquality/index.aspx (accessed 13 January, 2011).

[5] Southgate L, Cox J, David T, Hatch D, Howes A, Johnson N, et al. The assessment of poorly performing doctors: the development of the assessment programmes for the General Medical Council’s Performance Procedures. Medical Education 2001;35(Suppl 1):2–8.

[6] Department of Health. Good doctors, safer patients. Proposals to strengthen the system to assure and improve the performance of doctors and to protect the safety of patients. A report by the Chief Medical Officer. London: Department of Health; 2006.

[7] Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. Fitness to practice — Annual report 2008. London: RPSGB; 2009.

[8] Seston EM, Hassell K. Pharmacy workforce census 2008: Main findings. London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain; 2009.

[9] Department of Health. The NHS Knowledge and Skills Framework (NHS KSF) and the Development Review Process. London: HM Stationery Office; 2004.

[10] National Clinical Assessment Service. Helping ensure safe pharmacy practice. London: National Patient Safety Agency; 2009.

[11] Hassell K, Jacobs S, Potter H, Prescott J, Schafheutle EI, Seston EM. Managing performance concerns about pharmacists: A report for the National Clinical Assessment Service. London: NCAS; 2010.

[12] Jacobs S, Seston EM, Hassell K, Potter H, Prescott J, Schafheutle EI. Defining and identifying performance concerns in community pharmacy. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2010;18(Suppl 2):29–30.

[13] Cox SJ, Holden JD. Presentation and outcome of clinical poor performance in one health district over a five-year period: 2002–07. British Journal of General Practice 2009;59:344–8.

[14] Schafheutle EI, Jee S, Hassell K, Noyce PR. What could the NHS appraisal system contribute to revalidation in pharmacy? Pharmaceutical Journal 2011;286:82.

[15] Ziaei Z, Schafheutle EI, Hassell K. Language proficiency of European trained pharmacists in Great Britain. Pharmacy Practice 2010;8(Suppl 1):57–8.

[16] EEA-qualified pharmacists. Available at: www.pharmacyregulation.org/regulating pharmacy/registration/registeringasa pharmacist/eeaqualifiedpharmacists/ index.aspx (accessed 15 January 2011).

[17] Rivers F. Who should test the English language skills of European pharmacists? Pharmaceutical Journal 2009;283:204–5.

[18] Tullett J, Rutter P, Brown D. A longitudinal study of United Kingdom pharmacists’ misdemeanours — trials, tribulations and trends. Pharmacy World and Science 2002;25:43–51.

[19] National Clinical Assessment Service. A review of the extension of the National Clinical Assessment Service to pharmacists: April 2009—June 2010. London: National Patient Safety Agency; 2010.

[20] Department of Health. Equity and excellence: Liberating the NHS. London: HM Stationery Office; 2010.