Key points

- Urinary tract infections are one of the most common conditions seen in female patients in general practice accounting for 1–3% of all GP consultations each year in the UK.

- Diagnosis of a UTI is primarily based on the presentation of typical signs and symptoms. Routine urine culture is unnecessary in uncomplicated lower UTIs unless diagnosis is in doubt.

- Over-the-counter treatments for UTIs currently available in community pharmacy only attempt to relieve the symptoms and do not address the bacterial infection.

- The Grampian project provided treatment of uncomplicated lower UTIs through community pharmacies by means of a Patient Group Direction for trimethoprim supported by a local protocol based on national guidance.

- The review of the various stages of this service development and subsequent roll-out suggests that community pharmacists are able to respond in a timely manner to UTI symptoms, with appropriate use of trimethoprim.

Introduction

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are one of the most common conditions seen in female patients in general practice (GP), accounting for 1–3% of all GP consultations each year in the UK[1]

. Symptomatic UTIs will affect 50% of women at least once in their lives, and the incidence increases with age[2]

. A patient who has three or more episodes of an acute UTI each year is said to have ‘recurrent’ UTIs[2]

and more than a quarter of women who have had a UTI will experience a recurrence[3]

. UTI is the second most common clinical indication for empirical antimicrobial treatment in primary and secondary care, and urine samples constitute the largest single category of specimens examined in most medical microbiology laboratories[4]

.

UTIs can be classified as either lower or upper UTIs. Lower UTI occurs when the infection is localised in the bladder (cystitis) or urethra (urethritis), whereas upper UTI involves the ureters or kidneys (acute pyelonephritis)[3]

. Typical symptoms of lower UTI include dysuria, urinary frequency and urgency, haematuria and polyuria. If patients present with the first two symptoms, dysuria with frequency, the probability of a UTI is greater than 90%[3],[5]

. If nausea, vomiting, fever, or flank, loin, low back pains are present, then pyelonephritis is generally considered[3],[6]

.

Although diagnosis of a UTI is primarily based on the presentation of typical signs and symptoms, urine is the most commonly received specimen in microbiological laboratories, and urinary dipstick tests are the most commonly used near-patient tests in primary care[3],[6]

. However, routine urine culture is unnecessary in simple lower UTIs unless diagnosis is in doubt. In this case, urinary dipstick tests may be appropriate to guide treatment and establish if a UTI is present[4]

.

Antibiotic treatment is usually unnecessary, especially as uncomplicated UTIs are often self-limiting and resolve in a few days without treatment[1]

. However, if symptoms are moderate to severe, an antibiotic is recommended and can shorten the duration of symptoms by one to two days[7]

. Alternatively, a delayed prescription can be issued and used by the patient if symptoms worsen or do not resolve within a few days.

Current evidence supports the use of a three-day course of trimethoprim (200mg twice daily) or nitrofurantoin (50–100mg four times daily) for non-pregnant women of any age with signs or symptoms of acute lower UTI[4]

.

Three days of antibiotic treatment in non-pregnant women with uncomplicated UTI achieves symptomatic cure, which is similar to five to ten days’ treatment, but with a lower risk of adverse effects and better patient compliance[4]

. Longer courses of antibiotic therapy should be considered in complicated UTI (e.g. pyelonephritis, recurrent UTIs and pregnancy).

Over-the-counter (OTC) treatments for UTIs currently available in community pharmacy only attempt to relieve the symptoms and do not address the the bacterial infection. Symptomatic treatments available include alkalinising agents, cranberry products and analgesia. Although urine alkalinisation with potassium or sodium citrate has been traditionally used to relieve the symptoms of UTI, there is little evidence to support its use[6]

. Cranberry has also been found to be of no benefit in the treatment of UTI; however, high doses may have a role in the prevention of recurrent infection[6]

. Analgesics, such as paracetamol or ibuprofen, may help to relieve pain in mild to moderate cases[3],[6]

.

Out-of-hours provision

Unscheduled care services are coming under increasing pressure to deliver timely and appropriate care to patients, and community pharmacies are a key supporting partner. One of the drivers for this research article was a 2012 analysis (unpublished data) of all NHS Grampian community pharmacist referrals to the local out-of-hours medical service, G-MED, which revealed that there were 569 community pharmacy referrals over a five-month period (April to August). Of those calls to G-MED, 13% were from patients with genito-urinary symptoms, and of these patients, 95% had symptoms related to lower UTIs, which resulted in a G-MED consultation or advice from a GP. In some instances, referrals were supported by the community pharmacist who voluntarily managed the provision of a patient’s urine sample dipstick test and communicated the results, along with other symptomatic information to the GP. In these cases, a prescription could be arranged without the patient attending G-MED.

In addition to these pharmacy referrals, G-MED itself recorded 3,219 calls (2.5% of total calls) coded as a lower UTI during the period 1 January 2012 to 31 December 2012. Attendances at accident and emergency (A&E) with a diagnosis of UTI during both the in-hours and out-of-hours periods from April 2010 to January 2013 averaged 75–78 per month (unpublished data). This activity at G-MED and A&E demonstrated the need for out-of-hours UTI diagnosis and treatment, and based on evidence from a previous study in Greater Glasgow and Clyde[1]

, NHS Grampian supported the development of a service to provide treatment of uncomplicated UTIs through community pharmacies.

Service implementation

NHS Grampian is one of the 14 regional health boards of NHS Scotland and is responsible for providing health and social care services to more than 500,000 people living in Aberdeen City, Aberdeenshire and Moray. Currently, there are 138 community pharmacies in NHS Grampian. This article describes the development, implementation and early outcomes of a community pharmacy-led service to diagnose and treat uncomplicated lower UTIs in women aged between 16 and 65 years. The service was originally developed to support unscheduled care presentations but was extended to provide care during all normal routine pharmacy opening hours.

The NHS Grampian project was developed to provide treatment of uncomplicated lower UTIs through community pharmacies by means of a Patient Group Direction (PGD) for trimethoprim, with the following aims:

- To provide safe, timely and appropriate access to treatment for uncomplicated lower UTIs in adult women aged 16 to 65 years;

- To provide triage and onward professional-to-professional referral of patients with presenting symptoms who fall outside the treatment protocol of adult women who are aged 16 to 65 years;

- To reduce the crude rate of contact with G-MED and attendances at A&E for uncomplicated lower UTIs in adult women aged 16 to 65 years;

- To demonstrate a cost-effective alternative to current treatment policy (via G-MED and A&E) of uncomplicated lower UTIs in adult women aged 16 to 65 years;

- To provide services with the appropriate assurances to antibiotic stewardship.

Method

Pilot pharmacy recruitment and training

In November 2013, 17 pharmacies made up the initial cohort to pilot the service, paperwork and treatment pathways. These pharmacies were situated in various localities across Grampian, and many had the longest weekend opening hours. These pharmacies were provided with in-house NHS Grampian face-to-face training sessions and support packs.

Around six months after the initial cohort of pharmacists had completed training, an assessment of feedback questionnaires from patients (received up to April 2014) indicated a high satisfaction score. To increase the number of patients passing through the service, and to allow a more robust assessment of outcomes, a further 24 pharmacies were recruited in April/May 2014. These additional pharmacies received the same in-house NHS Grampian face-to-face training session and support packs.

Training after pilot roll-out

The launch of a new UTI training package on the NHS Education for Scotland (NES) portal introduced an e-learning tool that supported the introduction of the service for newly recruited pharmacies from September 2016. Pharmacists who wished to provide the service now undertook the NES training pack ‘Urinary Tract (PGD training)’.

Figure 1: Pharmacy poster advising patients of the new service

Source: Courtesy of NHS Grampian

Raising awareness of the service, as well as the common symptoms of urinary tract infections, was achieved through use of posters and promotional adverts.

Treatment pathway and documentation

A protocol for the assessment and treatment of uncomplicated lower UTIs in adult women aged under 65 years, by community pharmacists, was developed. This was based on Health Protection Agency (HPA) guidance[4]

with local protocols integrated to ensure continuity and equity of care. The protocol also received approval from the Scottish Antimicrobial Prescribing Group (SAPG).

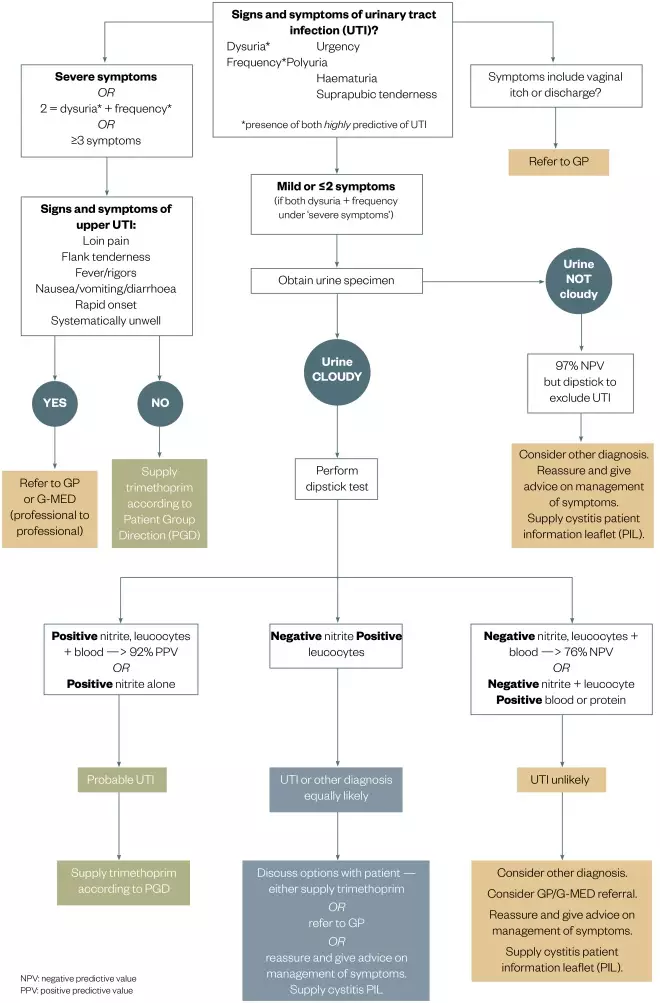

An example of a poster informing patients of the pharmacy service can be seen in Figure 1. Women who presented with an uncomplicated UTI with no previous treatment for this particular episode could be treated for three days with trimethoprim (as assessed by the agreed criteria), the antibiotic of first choice in the Grampian Joint Formulary. Women deemed not to have a UTI were offered general advice (see Figure 2: Community pharmacy treatment flow chart).

Figure 2: Community pharmacy treatment flowchart for the management of suspected urinary tract infection (UTI) in non-pregnant females aged 16-65 years

Source: Courtesy of NHS Grampian

Patient Group Direction (PGD) for the supply of trimethoprim for the treatment of uncomplicated UTI by nurses and pharmacists within NHS Grampian. Only to be used if patient has no exclusions under PGD.

Results

Pilot audit of patient opinion

As part of the initial service implementation, a small audit of patient views and opinions was undertaken. All patients presenting to the pharmacies in the pilot phases of the service (n=41) were asked if they would be prepared to complete a confidential 16-question audit questionnaire (click here to see the ‘Patient feedback form’) after they had the consultation with the pharmacist. Completed anonymised questionnaires were returned in sealed envelopes directly to the Pharmacy and Medicines Directorate so patients could provide any comments without fear that their local community pharmacist would know their views of the service. Data from these forms were entered into a Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) database for collation and analysis.

A total of 85 completed patient satisfaction questionnaires were received by December 2014 and analysed using SPSS. These data represent 24% of the 349 patients seen by community pharmacists to December 2014. It is acknowledged that this represents only a small sample of patients presenting for treatment and, as such, cannot be taken as representing the total treated patient group.

The audit indicated that the pharmacists saw patients quickly, with around 90% of patients seen in less than ten minutes, and some patients commented that this process was quicker and easier than getting an appointment with their GP. More than 70% of patients were seen in a pharmacy less than five miles from their home. Patients were also asked to rate the service on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being excellent. The median score and mode was 10 (range 7–10).

Of the 85 patients who returned patient satisfaction questionnaires, 87.1% (74 patients) had received a supply of trimethoprim to treat an uncomplicated UTI. When asked ‘Where would you have gone if this service had not been available?’, the majority of respondents indicated they would have gone to their GP. A breakdown can be seen in Table 1.

| Patients (n) | Patients | |

|---|---|---|

| GP | 42 | 49.4% |

| Pharmacy | 12 | 14.1% |

| G-MED/Accident & Emergency | 8 | 9.4% |

| NHS24 | 7 | 8.2% |

| Unsure | 7 | 8.2% |

| Self-treat at home | 5 | 5.9% |

| No response | 4 | 4.7% |

| Total | 85 | 100% |

Initial service provision analysis of pilot phases

The results below relate to forms and questionnaires for claims received up to December 2014 for the pharmacies (n=41) in the pilot phases of the service.

The data analysis was based on 349 patient assessment forms completed by community pharmacists. Patient forms and pharmacy claims were received from 28 (68%) pharmacies of those signed up to the PGD. On follow-up with pharmacies where low numbers or no patients were treated, it was apparent that while a small number of patients were presenting with UTI symptoms, they frequently fell outside of the inclusion criteria (e.g. >65 years, or male patients). Consequently, a patient assessment form was not completed.

The number of pharmacist assessment forms completed and submitted does not represent the total number of patients presenting with UTI symptoms in these community pharmacies during this time period. Some patients aged >65 years and men had been excluded, before any required paperwork was completed.

Of the 317 patients seen, 90.8% were registered with Grampian GPs, 16 patients (4.6%) were registered with other Scottish Health Board GPs and 3 patients (1.1%) were registered with GPs in other parts of the UK. The mean age of patients seen was 38.37 years.

Patients presented more often on a Friday and Saturday, as the documented time and day of the consultation shows (see Table 2). This was to be expected from the target patient group in this pilot. A greater number of consultations took place in the afternoon and after 6pm than in the morning. Missing data may in part be due to data being incomplete when submitted but also due to obliteration of the day/time columns when obscuring the patient details to ensure confidentiality.

| Time | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day | Not stated | AM | PM | After 6PM | Total |

| Not stated | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Monday | 2 | 15 | 21 | 3 | 41 |

| Tuesday | 5 | 9 | 24 | 3 | 41 |

| Wednesday | 3 | 12 | 21 | 2 | 38 |

| Thursday | 3 | 11 | 17 | 6 | 37 |

| Friday | 9 | 28 | 27 | 3 | 67 |

| Saturday | 6 | 36 | 47 | 4 | 93 |

| Sunday | 0 | 11 | 19 | 0 | 30 |

| Total | 30 | 122 | 176 | 21 | 349 |

A treatment flow chart was provided to support pharmacists in their clinical decisions (see ‘Figure 2: Community pharmacy treatment flow chart’). In respect of the protocol, urine sample testing is not required if the patient presents with both dysuria and frequency, as this represents a probability of a UTI of > 90% (see Table 3 for the presentation frequency of these two symptoms). A total of 283 patients (81.1%) presented with this combination of symptoms, indicating that urine testing was not required. However, 204 patients (58.5%) provided a urine sample, which was dipstick-tested using Multistix® SG (Siemens). Of those urine samples tested, 64.3% were reported to be cloudy (12% not stated), 73.5% were positive for leucocytes, 33% positive for nitrites and 71% positive for blood.

This was a new service in pharmacies and while there was not a requirement under protocol, if the patient provided a sample, pharmacists felt obliged to dipstick it both for their own and the patient’s reassurance. We did not analyse the effect of dipstick versus no dipstick on decisions to treat. The project was not undertaken as a formal clinical trial with rigorous data collection around decision-making so it has, therefore, not been possible to fully evaluate these aspects of the service.

| *Dysuria defined as: patient experiences pain, burning or discomfort upon urination | |||||

| Frequency of micturition present (numbers of patients) | |||||

| Not stated | No | Yes | Total | ||

| Dysuria symptoms present* (numbers of patients) | Not stated | 1 | 0 | 4 | 5 |

| No | 0 | 7 | 41 | 48 | |

| Yes | 1 | 12 | 283 | 296 | |

| Total | 2 | 19 | 328 | 349 | |

Table 4 shows the number of patients who were provided with a course of trimethoprim by the pharmacy. A total of 299 (85.7%) were treated with trimethoprim.

| Number of patients | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 299 | 85.7% |

| No | 40 | 11.5% |

| Not stated | 10 | 2.8% |

| Total | 349 | 100% |

Table 5 shows the disposition of the patients and whether they were referred on for other treatment. The difference between the number of patients treated by community pharmacy and the number of patients receiving trimethoprim reflects the pharmacist providing treatment for a non-UTI condition.

| Number of patients | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Treated by pharmacy (urinary tract infection (UTI) & non-UTI) | 302 | 86.5% |

| Referred for treatment (non-UTI) | 13 | 3.7% |

| Referred for treatment (UTI) | 21 | 6% |

| No referral made | 5 | 1.4% |

| Not stated | 8 | 2.3% |

| Total | 349 | 100% |

G-MED referrals

Referrals to G-MED from the initial 17 pilot pharmacies were analysed for the months of January to May 2014 to determine what type of referrals were being undertaken and if they were appropriate (see Table 6). As expected, referrals reflected the exclusion criteria from the service specification and trimethoprim PGD but qualitative analysis also indicated referrals for potential systemic illnesses or upper UTIs with symptoms of fever.

| Reason | Number |

|---|---|

| Female patients aged over 65 years | 2 |

| Male patient | 1 |

| Child (under 16) | 1 |

| Previous UTI in past 6 months | 4 |

| Pregnant patient | 1 |

| Reduced kidney function | 1 |

| Trimethoprim not indicated | 1 |

| Pharmacist not signed up to Patient Group Direction (PGD) | 5 |

| Treated on PGD and not resolved | 1 |

| Symptomatic, dipstick negative | 1 |

| Other symptoms/complications | 1 |

| Total | 19 |

Updated service provision analysis

Following the initial pilot phases, the service continued to be rolled out to additional pharmacies which expressed an interest in participation. This was made easier by the introduction of the e-learning module. The anonymised patient treatment assessment forms, which support the diagnostic process, continue to be submitted as proof of service provision. The data analysis described below is based on 1,464 patient forms submitted during the six months from March 2016 to August 2016, the details from which were entered into a SPSS database. Patient forms and pharmacy claims were received from 72 pharmacies during this period.

Of the patients seen in community pharmacies, a total of 1,373 patients (93.8%) were registered with a Grampian GP practice, and 26 patients (1.8%) were registered with other Scottish Health Board GPs or with GPs in other parts of the UK. A total of 64 patients (4.4%) did not state their GP practice or it was not visible on the assessment form. One patient was noted not to be a UK resident. The mean age of patients seen was 42.8 years.

From the documented time and day of the consultation it can be determined that there was generally an even spread of consultations across the week, with an increased number after the weekend. This is in contrast to the initial results which showed a greater peak of presentations on a Friday and Saturday. This was to be expected as the service changed from an out-of-hours focus to a general ‘anytime’ service. There are more consultations in the afternoon and after 6pm than in the morning.

As mentioned earlier with regard to the protocol, urine sample testing is not required if the patient presents with both dysuria and frequency; 1,123 patients (76.7%) presented with this combination of symptoms, indicating that urine testing was not required. However, 883 patients (60.3%) provided a urine sample that was dipstick-tested using Multistix® SG (Siemens). The additional urine testing may be a function of the community pharmacist wanting to ensure correct diagnosis in the early stages of the introduction of a new service, along with patient expectation where they had already presented to the pharmacist with a urine sample. Of those urine samples tested, 70% were reported to be cloudy, 83.6% positive for leucocytes, 34.3% positive for nitrites and 69.2% positive for blood.

A total of 1,063 patients (72.6%) were documented as being treated with trimethoprim, 336 patients (25%) were not treated by the pharmacy for a UTI and there were missing data for 35 patients (2.4%). Patients who were not treated by community pharmacy for a UTI included those referred for a medical assessment, those who were assessed as not requiring any treatment for their symptoms, or those had symptoms suggestive of alternative diagnosis (e.g. vaginal thrush). A total of 265 patients (18.1%) were referred for further treatment, either to their own GP practice or to out-of-hour services.

As part of the evaluation of the pilot, it was important to identify any potential risks resulting from pharmacists providing trimethoprim for the treatment of UTIs. Analysis of the pharmacist assessment forms (by an antibiotic pharmacist and the author of this article) indicated that there had not been any inappropriate supply of trimethoprim, or over-referral. More urine dipstick testing may have occurred than was required under the protocol, but this has not resulted in samples being sent to the laboratory for further testing.

While this may take up more of the pharmacist’s time, it does not represent any clinical risk, and may provide reassurance to the pharmacist and patient on the diagnosis obtained from the clinical discussion. The cost of an additional strip for testing was minimal and patients were asked to take their urine samples home for disposal via their own toilet.

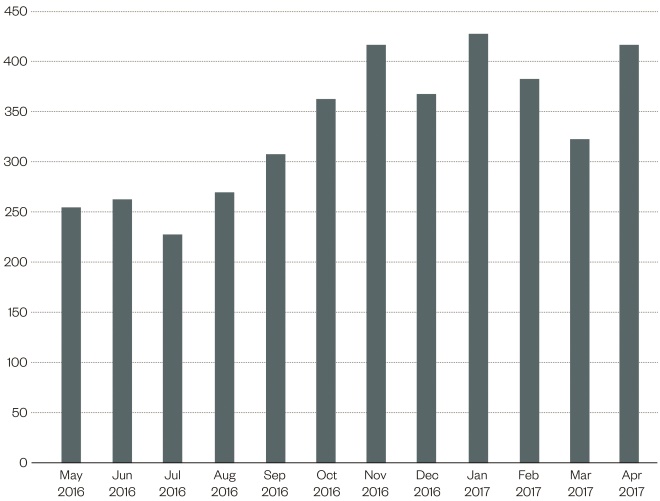

The number of patients treated by community pharmacy continues to increase, evidenced by increasing claims for payment. Figure 3 shows the payment claims received from May 2016 to April 2017, where claimants increased from 33 pharmacies to 71 pharmacies. Not every pharmacy offering this service treats a patient every month, thereby treatment-related claims are not submitted for each pharmacy for a patent every month. During May 2016 to April 2017, a total of 4021 patients were seen and treated by community pharmacists. This is likely owing to an increasing awareness of the services, increasing numbers of participating pharmacies, and some referral from out-of-hours services and GP practices.

Figure 3: Patients treated in community pharmacy for urinary tract infection (UTI) between May 2016 and April 2017

Source: Courtesy of NHS Grampian

The graph shows the payment claims received from May 2016 to April 2017, where claimants increased from 33 pharmacies to 71 pharmacies.

Analysis of prescribing information system data and subsequent antibiotic usage

A further audit was carried out in September 2016, using the NHS Scotland Prescribing Information System (PIS) prescribing data. Patient-level data were analysed for patients who had received a prescription for trimethoprim via a community pharmacy to determine whether they also received another antibiotic from their GP in the same or next month; 341 of 446 patients (76.5%) treated January to April 2016 had a Community Health Index (CHI) capture. The CHI is a population register that is used in Scotland for healthcare purposes and the CHI number uniquely identifies a person on the index. Of those 341 patients, 30 patients (8.8%) had received an antibiotic prescription after the pharmacy treatment, which for 25 patients (7.3%) were in the same or next month.

Analysis of the prescriptions for these 25 patients indicated that 18 patients (5.3%) were retreated for the same UTI infection. When cross-referencing CHI for these 18 patients against the NHS Grampian microbiology results database, it was noted that 11 patients had a record of a urine sample being sent for culture and seven of the treated patients did not have any records of urine samples being sent to the laboratory. Where samples were tested, four patients (out of 11) were noted to be trimethoprim-resistant. Seven patients received trimethoprim (of which two were for long-term treatment), eight received nitrofurantoin, one ciprofloxacin, one doxycycline and one co-trimoxazole.

Discussion and conclusion

The review of the various stages of this service development and subsequent roll-out suggests that community pharmacists are able to respond to UTI symptoms with appropriate use of trimethoprim. Re-treatment levels did not appear to be high when assessed using PIS data and were lower than those observed and reported in similar local audits of GP prescriptions (unpublished data). This gives some reassurance that re-treatment was not occurring very frequently, although the patient cohorts are likely to be different.

One of the greater risks of this service is the potential to miss a more serious diagnosis that should have been referred as a matter of urgency. The limited G-MED referral information does suggest that appropriate referrals were being made and there are no reports, to date, of patients who have presented elsewhere having been treated inappropriately by the pharmacist.

Patient numbers in the pilot study were not sufficient to be able to demonstrate any decrease on unscheduled care appointments or other benefits to GPs/G-MED or A&E, although the G-MED referrals indicate that only complex or non-protocol UTIs were being passed for further medical review and that pharmacies were dealing with significant numbers of symptomatic patients eligible for treatment.

Patient acceptability for this service has been very high and the short waiting times of around ten minutes observed in the pilot for most patients offers a service responsiveness that is unmatched by other providers.

As of 17 April 2017, a total of 200 pharmacists in 104 pharmacies (78.8% of pharmacies in Grampian) are signed up to the PGD. Patient numbers have increased as more pharmacists sign up to the PGD and patients become aware of the service. On average, in excess of 300–400 patients per month were managed by the pharmacy service as the project moved forward into 2017. Further patient satisfaction audits will be undertaken to determine how the service can be maintained and improved, and NHS Grampian is looking to how this service can be built upon to further support unscheduled care, be it within core hours or outside.

In developing the protocol for the treatment of women with a UTI, cognisance was taken of the risk factors for more complex or resistant disease. Exclusion of older and younger women, as well as those with an indwelling catheter, some pre-existing disease and recurrent infection was intended to reduce the risk of pharmacists treating patients with potential resistant organisms or where further investigations would be required. We know that UTIs are the most common cause of Escherichia coli bacteraemia, and while the cohort of women treated by community pharmacists is not in the highest risk groups for bacteraemia, prompt treatment may help to prevent some bloodstream infections.

The service was designed primarily to improve access for women and take pressure off GP practices at a time of increasing concerns over GP capacity. The protocols developed are similar to those that would be followed in GP practice. It has not been possible to determine, to date, any effect on GP appointments and further work would be needed to assess changes in behaviour of patients.

As with any use of an empirical antibiotic, there is the risk that the organism being treated may not be sensitive to trimethoprim, but some of the follow-up work suggests that this has not been a major issue, although further analysis will be required in the future to ensure that this remains the case. Trimethoprim resistance is being seen locally in laboratory samples of urine sent for testing, but there are no robust local data to indicate what proportion of women being treated empirically for a UTI are carrying resistant organisms. The delicate balance between providing timely and effective care for patients and maintaining good antibiotic stewardship will always be difficult.

Improving access to treatment via community pharmacists has been a key part of NHS Scotland policy as encompassed by the Community Pharmacy Minor Ailments Service. This allows eligible patients to register with, and use, a community pharmacy as the first port of call for the treatment of minor ailments. The addition of the treatment of uncomplicated UTIs by community pharmacists provides a logical extension to this existing service.

A community pharmacist UTI treatment service has now been picked up by the Scottish government as part of a national service provision by community pharmacies.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the following people for their contributions, which have helped facilitate this article: Gillian Macartney, specialist antibiotic pharmacist; Kate Livock, project manager — unscheduled care; Ann Smith, lead pharmacist; Leah Dawson, corporate communications officer; Deidre O’Brian, consultant microbiologist; Linda Harper, associate director of nursing (practice nursing); Claire Milne, administrative assistant; and Marie Livingston, administrative assistant.

Financial and conflicts of interests disclosure

The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. No writing assistance was used in the production of this manuscript.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] Booth JL, Mullen AB, Thomson DAM et al. Antibiotic treatment of urinary tract infection by community pharmacists: a cross-sectional study. Br J Gen Prac 2013;63(609):e244–e249 doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X665206

[2] Al-Badr A & Al-Shaikh G. Recurrent urinary tract infections management in women: A review. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 2013;13(3):359–367. PMCID: PMC3749018

[3] Car J. Urinary tract infections in women: diagnosis and management in primary care. BMJ 2006;332(7533):94–97. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7533.94

[4] Health Protection Agency. Guidance for primary care on diagnosing and understanding culture results for urinary tract infection (UTI). Updated 2014. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/urinary-tract-infection-diagnosis (accessed January 2018)

[5] Bent S, Nallamothu BK, Simel DL et al. Does this woman have an acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection? JAMA 2002;287(20):2701–2710. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.20.2701

[6] Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. SIGN 88: Management of suspected bacterial urinary tract infection in adults. A national clinical guideline. Updated July 2012. Available at: http://www.sign.ac.uk/sign-88-management-of-suspected-bacterial-urinary-tract-infection-in-adults.html (accessed January 2018)

[7] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Urinary tract infection (lower) — women. July 2015. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/urinary-tract-infection-lower-women (accessed January 2018)