Key points

- Providing pharmaceutical care in the emergency department (ED) facilitates safer, more appropriate patient care, while also being more efficient to pharmacists when resolving clinical queries and less disruptive to clinicians if undertaken later in the inpatient stay.

- Pharmaceutical care in the ED improves governance around prescribing and promotes greater adherence to hospital guidelines.

- Including pharmaceutical care in the ED may help increase the use of patients’ own drugs and the onward transfer of patients’ drugs to wards, meaning less re-dispensing of drugs, a reduction in pharmacy workload, reduced costs, timelier drug administration and a reduction in missed doses.

- Pharmacists working in the ED require a good knowledge of evidence-based medicine combined with well-developed interpersonal skills to ensure they are effective in successfully influencing changes in prescribing behaviour and practice.

- The service pharmacy provides to the ED is highly valued by clinicians of all grades and they consider that it contributes significantly to their medical education.

Introduction

The NHS is currently facing a range of complex pressures driven by the changing health and social care needs of the population, mainly owing to rising levels of chronic and complex conditions, and an increasing number of older people requiring long-term care[1]

.

In 2018, an average of 67,000 people attended a hospital emergency department (ED) in England each day; an increase of 3.9% compared with 2017. Furthermore, in 2018, an average of 12,835 people were admitted to hospital via an ED each day. This is an increase of 6.7% from 2017 and an increase of 22.9% from 2013[2]

. Consequently, many hospitals are struggling to cope with increasing demand for ED services — a situation that is particularly severe during the winter months. Bed occupancy rates in hospitals continue to rise year on year, and the ambulance service is also under significant stress[3]

.

In 2000, a government policy was launched requiring that 95% of patients attending EDs must be seen, treated and either discharged or admitted within four hours of arrival. As a result, some organisations established new pharmacy services to provide pharmaceutical care and optimise medicines use in EDs in an effort to meet this target. Other drivers for new services include patient-group directions, non-medical prescribers, National Patient Safety Agency alerts (including safer use of injectable medicines), National Institute for Health and Care Excellence requirements to implement medicines reconciliation on admission, and pharmacy technician assessment of patients’ own drugs (PODs) and stock management[4]

.

Therefore, pharmacy services within EDs have been developing since the early 2000s[5]

, with the first full-time clinically oriented ED pharmacist post being created in Nottingham in 2002[6]

. This was later followed by funding for ten full-time pharmacists in Northern Ireland in 2004; one in each ED[4]

. By 2008, the role of clinical pharmacists in EDs (based on a UK-wide 40-hospital site questionnaire) demonstrated that pharmacists were supporting clinicians with guideline development and review, patient group directions, provision of training, provision of advice and taking drug history[7]

. More recently, evidence from conference proceedings at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust showed that clinical pharmacists in the ED has broadened their roles to include earlier medicines reconciliation (including allergy confirmation), reducing missed and delayed doses, supporting safer prescribing in a high-risk environment, avoidance of adverse drug reactions, and the provision of timely medicines information and advice[7]

. Several examples of good practice in UK EDs now exist, including those at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in London, Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, and Lewisham and Greenwich NHS Trust in London[7]

.

However, while the value of clinical pharmacy services in reducing inpatient length of stay, reducing drug costs, improving the quality of prescribing and reducing readmissions have been demonstrated[4]

, the impact of these services in EDs is less well established. In the United States, pharmacists working in EDs have been shown to reduce prescribing errors by up to 67%[8]

. Recently published research from Greenwood et al. at the University of Manchester sought to define and describe the role of pharmacists working in ED, including those managing patients in a more enhanced medical role[9]

. A stated aim of the research is to develop methods to evaluate the impact of pharmacists working in EDs on patient outcomes, including reducing medicine errors, improving prescribing appropriateness and reducing length of stay[8]

.

While it is essential that patients in EDs receive the same standard of care as other inpatients[4]

, there remain geographical variations in the provision of pharmacy services in EDs. For example, until recently, pharmacy services in EDs in Wales were not well developed. However, partly with an awareness of the success of the ED service at Morriston, in the winter of 2018–2019 the Welsh government funded an all-Wales evaluation of pharmacy services in EDs, with the aim of informing future developments prospectively.

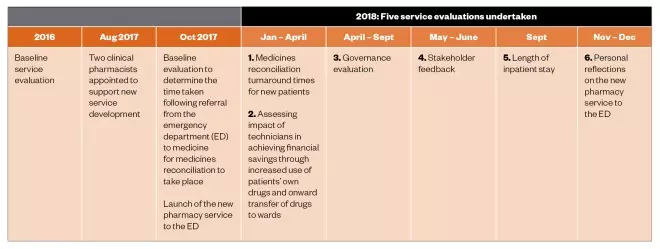

This paper describes the development of the new pharmacy service to a single ED in Morriston Hospital (an acute, tertiary-referral hospital) managed by Swansea Bay University Health Board in Wales, through provision of traditional clinical pharmacy roles already established for inpatients at ward-level, and evaluates the impact of the new service. A timeline of this evaluation is detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Timeline for the implementation and subsequent evaluation of the new pharmacy service to the emergency department at Morriston Hospital, Wales

Background

The economic environment that the NHS finds itself in is challenging. Consequently, there is an increasing emphasis on reducing the length of hospital inpatient stay for medical patients. As well as being better for patients, reducing length of stay releases capacity in the system that can be used for other patients and enhances patient flow[10]

. Furthermore, the impact of reducing length of stay on the workload of pharmacy, in addition to patient monitoring and the provision of advice during an inpatient stay, is substantial[11]

.

With 722 beds and around 70,200 emergency admissions each year (unpublished data on file), the ED at Morriston Hospital is the largest in the health board and one of the busiest in Wales. Data from April 2018 onwards suggest that 200 patients are admitted as an inpatient under the care of an ED medical consultant each week, with an average length of inpatient hospital stay for each patient of eight days. While pharmacists at Morriston Hospital had participated in consultant post-take medical ward rounds (PTWR) for many years and provided a very limited service to the ED during office hours, there was increasing recognition that the pharmacy service had to change and adapt to meet the increasing demands being placed upon it.

In order to meet the unprecedented demand in unscheduled care, there was a requirement to work more efficiently. The aim was to redesign the pharmacy service to provide pharmaceutical care as close to patient admission in the ED as possible and, ideally, before the time of first senior clinical review.

Baseline evaluation

In 2016, a baseline service evaluation was undertaken by pharmacists to try to ‘quantify’ the pharmaceutical care provided to patients referred to medicine following admission from the ED. These range from complex patients with multiple comorbidities to patients needing admission while greater provision is made to assist them in the community.

Overall, 309 patients referred to medicine from the ED were prospectively reviewed by pharmacists to establish if, following clerking by the medical team, the patient required any clinical contributions from the pharmacy team in relation to drug omissions, prescribing errors, therapy optimisation, drug selection or drug monitoring. The results of the baseline evaluation showed that a pharmacist made a clinical contribution to patient care in 83% of cases in the acute setting:

- Patients requiring at least one intervention from pharmacy (i.e. either drug omissions, prescribing error) or clinical contributions made) = 255/309 (83%).

- Patients with at least one drug omitted = 133/309 (43%).

- Patients with at least one prescribing error = 69/309 (22%).

- Patients with at least one pharmacy contribution to care = 188/309 (61%).

Ensuring that interventions were actioned by medical staff in a timely manner proved challenging. Following admission, the junior doctor responsible for the ongoing care of the new patient was often not involved in the discussions and clinical decisions made on admission. As a result, there was often justifiable reluctance for the junior doctor to make further changes to the treatment plan following consultant review. Furthermore, these conversations were often conducted by telephone, with the doctor located on a different ward from the patient in question, and often interrupted the doctor during their own consultant ward round, making actioning suggestions and requests difficult.

Subsequently, a review of 53 patients showed that the average time following referral of a patient from the ED to medicine for medicines reconciliation to be undertaken was 12 hours and 15 minutes.

As a result of this analysis, it was decided that the service should be redesigned to improve the efficiency when undertaking medicines reconciliation and actioning pharmacists’ clinical contributions to care, which could bring benefits to the pharmacy, doctors and, most importantly, patients.

New service

In October 2017, the pharmacy service to medical patients changed to a new way of working that enabled earlier medicines reconciliation and earlier clinical contributions to patient care in the ED.

The aims of the new service are to:

- Reduce medicines reconciliation turnaround times for new patients;

- Increase the use of PODs, and onward transfer of PODs and individually dispensed patients’ drugs to wards;

- Improve the quality of prescribing (including ensuring a thromboembolism risk assessment is undertaken and the allergy section of the inpatient chart is completed);

- Improve adherence to hospital guidelines (including antibiotics guidelines);

- Improve identification of possible medicines-related admissions;

- Improve timeliness of medicines administration, especially critical medicines;

- Enhance education of junior and senior doctors relating to factors underpinning any prescribing advice offered (e.g. drug selection decisions, drug interactions, evidence-based practice, adverse effects, therapeutic drug monitoring).

A team of four pharmacists and two pharmacy technicians provide clinical pharmacy services to new patients at, or shortly after, admission (i.e. around the time of clinical decision-making and the prescribing of drugs for newly admitted patients) from 08:00 to 16:00, five days per week. The pharmacy team divides its time between the ED, the acute medical-admission wards and other clinical commitments, depending on the workload in the ED.

‘Front-loading’ pharmaceutical care is the process of collating and resolving as many pharmaceutical issues relating to a patient’s medicines as early as possible following admission to hospital. This includes undertaking medicines reconciliation; clarifying all the medicines a patient is prescribed and taking (or not) on admission to hospital; rectifying any prescribing errors made following admission and initial clerking; documenting intentional changes to prescribed therapy; and optimising therapy by contributing to therapeutic decision-making through the proactive provision of clinical advice.

Prior to the change in service delivery, the Morriston Hospital ED had not previously employed a pharmacy technician to work in the department. In addition to assisting with medicines reconciliation, pharmacy technicians undertake several additional roles to assist in the smooth running of the ED. These include processing take-home prescriptions, obtaining stock and non-stock items from pharmacy, identifying and prioritising the supply and administration of ‘critical drugs’ (e.g. anticoagulants and anti-epileptics), and improving governance in relation to medicine storage.

As part of the medicines reconciliation process, technicians liaise with patients and their partners/carers to maximise the utilisation of PODs through requests to bring medicines into hospital for drugs not required urgently. Furthermore, technicians also help ensure PODs and individually dispensed items are transferred with the patient when they are moved from the ED to a ward. Both activities help avoid the need to redispense medicines, thus saving money and reducing pharmacy workload while also ensuring the medicine is available for timely administration.

Methods

In 2018, five service evaluations were undertaken to assess the impact of the new service, comprising:

1. Medicines reconciliation turnaround times for new patients

A medicines reconciliation pro forma (see Supplementary file 1) was designed for use in the ED to document a complete list of medicines being taken by a patient on admission (including over-the-counter and herbal medicines), any compliance issues identified by the pharmacy team and any other drug-related information considered relevant to the admission. The sources of information used to collate this are listed on the pro forma.

The pro forma is either used to inform the admitting doctor face-to-face of any medicines and medicine-related issues regarding patients on admission, or it is inserted into the medical clerking pro forma for later reference by clinicians.

Between January 2018 and April 2018, an evaluation was performed to determine the average time needed to undertake medicines reconciliation for new patients. This was determined as the time from the patient’s referral from the ED to medicine (as documented in the ED medical notes) to the time a member of the pharmacy team undertook the medicines reconciliation.

2. Assessing the impact of pharmacy technicians in achieving financial savings through increased use of patients’ own drugs and onward transfer of drugs to wards

An analysis of the ad hoc work performed by pharmacy technicians in the ED was undertaken over a six-week period between January 2018 and April 2018. This was to quantify the savings realised by technician activity in increasing the use of PODs and onward transfer of drugs to wards from the ED.

Pharmacy technicians maintained a list of medicines and quantities that they would have had to supply from pharmacy to the ED or medical admissions units (MAUs) if they had not undertaken this activity. The costs of supply (had supplies been made) were then calculated. The total time that pharmacy technicians spent in ED was also used to calculate the cost saving per hour.

3. Governance evaluation

A pharmacist (for this part of the evaluation, the pharmacists were band 6 and 7) in the two MAUs reviewed inpatient treatment charts to determine if:

- The allergy status had been documented on the inpatient chart;

- A thromboembolism risk assessment had been conducted (assessed by the prescription of thromboprophylaxis or documentation to indicate thromboprophylaxis was inappropriate or not required);

- For patients prescribed antibiotics:

- The indication for the antibiotics was stated;

- The intended duration/review date for the antibiotics was stated;

- The prescribed antibiotics were chosen in accordance with Swansea Bay University Heath Board guidelines (or if non-adherence to guidelines was detected, whether non-adherence had been clinically justified).

Data were collected prospectively and consecutively as part of clinical duties and when possible around other work commitments permitted.

4. Stakeholder feedback

In May 2018, a paper questionnaire was circulated to medical clinicians working in the ED requesting their views and attitudes regarding the new pharmacy service provided by the pharmacy team in the ED.

The questionnaire asked 12 questions with a 5-point Likert scale, where ‘1’ indicated ‘strongly disagree’ and ‘5’ indicated ‘strongly agree’. The questionnaire also included two free-text questions that requested clinicians provide comments about the new service (e.g. anything particularly good or bad, or ways in which the pharmacy service could be improved) and was completed anonymously.

5. Length of inpatient stay

Where data were available, patients included in the governance evaluation (service evaluation 3) were reviewed to determine their average length of hospital inpatient stay (i.e. from ward transfer to discharge) and their average length of stay in the ED (i.e. time from presentation in the ED to ward transfer).

Data were obtained retrospectively (between April 2018 and September 2018) from the hospital computer system and reflected the time from hospital admission to discharge.

Results

1. Medicines reconciliation turnaround times for new patients

The evaluation of the new service was performed on days when the service was fully staffed between January 2018 and April 2018. Overall, the time taken to undertake medicines reconciliation was reviewed for 285 patients. For these patients, the average time taken to undertake medicines reconciliation was two hours. This is a reduction compared with the baseline evaluation, where a review of 53 patients showed that the average time taken to undertake medicines reconciliation was 12 hours and 15 minutes.

Medicines reconciliation information is now often available before the patient has been formally medically clerked and, crucially, is available to the consultant at the time of the first consultant review (i.e. when planning decisions about prospective therapy or considering medicine-related causes for admission).

2. Assessing the impact of pharmacy technicians in achieving financial savings through increased use of patients’ own drugs and onward transfer of drugs to wards

During a six-week period in early 2018 (exact dates not recorded), pharmacy technicians spent a total of 52 hours working in the ED, during which time the value of PODs obtained from home was £409.20 and the value of drugs transferred to wards from the ED was £359.71. This resulted in a total saving of £759.91 (£14.61 per hour worked), meaning that the activity of technicians in the ED in preventing unnecessary drug supply and additional workload almost pays for their costs alone, with the additional benefits outlined above being effectively free. There are no data to show how many patients these savings came from.

3. Governance evaluation

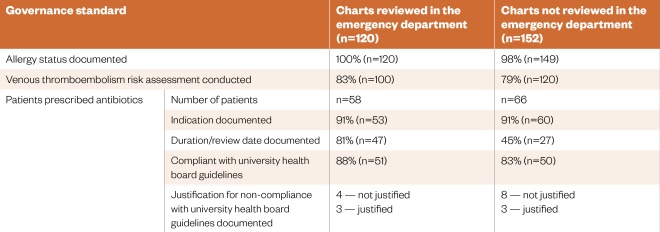

During April 2018 to September 2018, 272 patients were evaluated by a pharmacist in the two MAUs.

Overall, 120 patients had drug treatment prescribed on an inpatient chart that had been reviewed by a pharmacist in the ED before being transferred to the MAU, while 152 patients had been transferred to the MAU without a review by a pharmacist in the ED. These 152 patients formed the control group.

The data demonstrate an improvement in most of the governance standards assessed (see Table 1).

Table 1: Governance standards used to assess the quality and safety of prescribing on inpatient charts reviewed/not reviewed by pharmacists in the emergency department

4. Stakeholder feedback

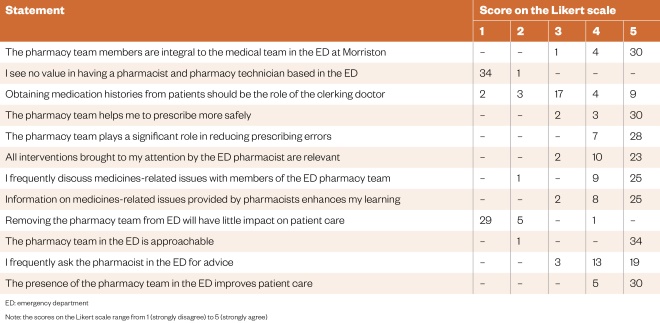

In total, 35 paper questionnaires were returned by consultants (n=11), registrars (n=8) and junior doctors (n=16).

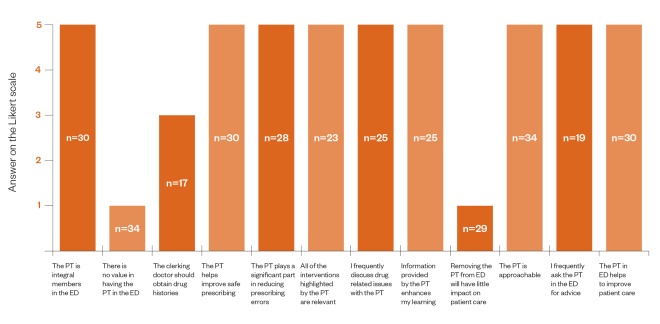

Results from the questionnaire showed that the pharmacy team is an integral part of the medical team in the ED, with 97% (n=34) of respondents strongly disagreeing with the statement “I see no value in having a pharmacist and pharmacy technician based in ED” (see Table 2, Figure 2 and Supplementary file 2). The pharmacy team is considered approachable for advice and clinicians agree that its clinical contributions lead to safer prescribing and improvements in patient care. Clinicians of all grades value the service in terms of contributing to their medical education.

Table 2: Feedback about the new pharmacy emergency department service at Morriston Hospital from 35 stakeholders, including 11 consultants, 8 registrars and 8 junior doctors using a five-point Likert scale

ED: emergency departmentNote: the scores on the Likert scale range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree)

Figure 2: Mode responses about the new pharmacy emergency department service at Morriston Hospital from 35 stakeholders, including 11 consultants, 8 registrars and 16 junior doctors using a five-point Likert scale

ED: emergency department; PT: pharmacy team Note: the scores on the Likert scale range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree)

While the small number of respondents does not permit statistical analysis of any differences in the answers given by different grades of clinician (consultants, registrars and junior doctors), there was uniformity in the responses given to each question using the rating scale.

Although not all respondents to the questionnaire chose to answer the free-text questions (questions 13 and 14), all responses to the two supplementary questions were positive with no negative comments (see Supplementary file 3). A selection of the comments verbatim are shown below:

Question 13: Please outline any positive or negative experiences of working with the pharmacy team in the ED.

Comments from consultants (n=7):

- “Our pharmacy colleagues are knowledgeable and frequently help with complex drug-related issues and obtaining patient drug information. I do believe they help with minimising drug errors significantly and also reduce workload for doctors by assisting us with medication-related issues while the doctor is dealing with other aspects of patient care.”

- “Less errors, easier decision making on post-take ward round.”

-

“Positive. [The team has]

have been a huge help in ED. In fact, on one of my PTWRs, I have had several useful discussions which then led to several discussions and teaching opportunities for the juniors present.”

- “It has been a positive experience all around and an educational one too.”

Comments from registrars (n=7):

- “I learn something useful every time I work with them on PTWRs.”

- “Hugely valuable service. Critical to patient care.”

- “Critically important in reducing drug errors/interactions early in admissions.”

Comments from junior doctors (n=14):

- “Always approachable, incredibly helpful and educationally excellent.”

- “Very approachable and knowledgeable. A great help when clerking or post-taking.”

- “It has always been beneficial to have the pharmacy team in the ED.”

- “I have found it very useful to have the pharmacists in the department and have often been waiting for them on arrival after nights!”

Question 14: Please provide any other feedback you consider appropriate.

Comments from consultants (n=3):

- “Excellent initiative to improve patient care and reduce prescribing errors.”

-

“[The team has]

been a great addition to the PTWRs and streamline the process. It’s good to have them highlight any potential interactions — and hence implications to patient care.”

Comments from registrars (n=4):

- “Fantastic service and helpful on PTWRs. Please keep it up.”

- “I would be very disappointed and concerned if this role was reduced/removed.”

- “The pharmacy team helps make the medical take more efficient and therefore safer.”

Comments from junior doctors (n=3):

- “Great service.”

- “Needs to be kept. Love the team.”

- “Continue providing pharmacy team service in the ED.”

5. The length of inpatient stay

Patients in the governance evaluation (n=272) had their length of inpatient stay reviewed. In total, 56 patients were excluded from the analysis because their hospital inpatient stay exceeded their ‘fit for discharge’ date, implying that their discharge was delayed for non-medical reasons (e.g. waiting for a nursing home placement or carers to be organised in the community). Analysis of the remaining 216 patients showed that patients who had received pharmaceutical care from a pharmacist in the ED had an average hospital inpatient stay of 7.21 days (n=98) compared with an average hospital inpatient stay of 6.31 days (n=118) for patients who had not been reviewed by a pharmacist in the ED (patients having moved directly to the MAU).

All patients (n=272) in the governance evaluation were also reviewed to determine their average length of stay in the ED. Data were available for 251 patients. The analysis showed that patients reviewed by a pharmacist in the ED stayed almost twice as long in the ED (17 hours and 41 minutes; n=111) when compared with patients moving directly to MAU without pharmacist review (9 hours and 30 minutes; n=140).

Discussion

Data show that the pharmacy service to the ED provides earlier medicines reconciliation, which can facilitate safer, more appropriate patient care. Furthermore, the service improves governance around prescribing and there is greater adherence to hospital prescribing guidelines.

Following the success of the medicines reconciliation pro forma, the format has now been incorporated into the medical clerking pro forma used by the clerking doctor.

The service has increased the use of PODs and onward transfer of patient’s drugs to wards, meaning less redispensing of medicines, a reduction in pharmacy workload, reduced costs, timelier medicine administration and a reduction in missed doses.

The service is highly valued by clinicians of all grades and, in their opinion, contributes to their medical education and makes a significant contribution to patient care. The feedback received from stakeholders in this service evaluation is similar to a previous evaluation, which assessed the satisfaction with, and confidence of, a range of staff (including 13 nurses and 11 doctors) in the pharmacist service to an ED at a large teaching hospital in England[12]

.

The increase in length of inpatient stay was an unexpected finding and may have occurred as a result of the small number of patients studied. Furthermore, correlation does not imply causation: it may have been caused by unmeasured confounding, meaning that patients reviewed by pharmacy in the ED are possibly ‘different’ from those that move from the ED to the MAUs without pharmacist review. Based on personal experience of working with medical patients in EDs over many years, one hypothesis to explain these findings could be that patients reviewed by pharmacy in the ED are usually more unwell and, therefore, spend more time in the ED before being transferred to an MAU. Patients in an ED have immediate access to doctors and nurses, which means that very unwell patients can be intensively treated by doctors, with close monitoring from nursing staff. Out-of-hours medical cover for medical wards is more limited and there are usually fewer nurses available to undertake the intensive monitoring necessary to safely manage extremely unwell patients. Consequently, patients who are more unwell tend to remain in the ED environment for longer, while less unwell patients who are medically stable (and therefore require less medical intervention and monitoring by nursing staff) are transferred to an MAU at an earlier time to release capacity in the ED.

It is also important to note that the pharmacy team provides cover for the ED from 08:00 to 16:00. At 08:00, the ED hosts a disproportionate number of patients who are more unwell awaiting senior review on the PTWR, having not been transferred from the ED overnight. Therefore, through being resident in the ED, patients who are more unwell receive earlier pharmaceutical care from pharmacists working in the ED. Between 08:00 and 16:00, the impact of this effect (more unwell patients remaining in the ED longer than less unwell patients) is not as pronounced because pharmacists work in the ED to review all patients.

This hypothesis is supported by the data showing that patients reviewed by pharmacy in ED were resident in ED for almost twice as long when compared with patients who moved to MAU without pharmacist review. While this does not provide proof of the hypothesis outlined above, it supports the belief that ‘front-loading’ pharmaceutical care first thing in the morning ensures that the most unwell patients receive pharmaceutical input at the earliest opportunity (i.e. at the time of clinical decision-making by the senior consultant), while patients in an MAU (who are usually less unwell) are reviewed by pharmacy a little later in the morning. However, additional data are necessary to confirm or refute this.

Limitations

The small sample sizes studied and lack of statistical analysis undertaken are both limitations of this evaluation.

It must be noted that while a Likert scale provides data regarding degrees of opinion, it does not provide understanding of the reason behind those numbers. Although two free-text questions were provided in the questionnaire, only a small number of respondents included more detail about their opinion of the service and why they felt it was positive.

Furthermore, the stakeholder questionnaire was only distributed to doctors. Prospectively, it would be interesting to evaluate responses from other healthcare professionals, most notably nursing staff in the ED.

Conclusion

Providing a pharmacy service to an ED is very similar to providing a clinical pharmacy service to an MAU. If a pharmacy service is at full capacity trying to manage an increasing number of unwell and frail patients, consideration should be given to providing a pharmacy service to the ED. However, there is no ‘one size fits all’ model and the service will need to adapt to the wider needs of the organisation.

Furthermore, staff providing the service will need to be selected extremely carefully. While the pharmacy role in an ED is a specialist one requiring a wide knowledge of medicines and evidence-based medicine for a variety of clinical conditions, interpersonal skills are equally as important to ensure the pharmacist is effective in successfully influencing changes in prescribing behaviour and practice.

A pharmacy service in the ED provides intangible benefits. Opportunities and further service developments will arise from closer working relationships with clinicians.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to extend special thanks to the medical pharmacy team, without whose enthusiasm, dedication and expert knowledge, none of this would have been possible, and to Roger Williams and Judith Vincent for their support.

Financial and conflicts of interest disclosure

The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. No writing assistance was used in the production of this manuscript.

References

[1] Addicott R, Maguire D, Honeyman M & Jabbal J; The King’s Fund. Workforce planning in the NHS. 2015. Available at: http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/Workforce-planning-NHS-Kings-Fund-Apr-15.pdf (accessed September 2019)

[2] Baker C. NHS key statistics: England, May 2019. 2019. Available at: http://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-7281/CBP-7281.pdf (accessed September 2019)

[3] House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts. Emergency admissions to hospital. 2014. Available at: http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201314/cmselect/cmpubacc/885/885.pdf (accessed September 2019)

[4] Collignon U, Oborne CA & Kostrzewski A. Pharmacy services to UK Emergency Departments: a descriptive study. Pharm World Sci 2010;32:90–96. doi: 10.1007/s11096-009-9347-3

[5] Henderson KI, Gotel U & Hill J. Using a clinical pharmacist in the emergency department. Emerg Med J 2015;32(12):998–999. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2015-205372.45

[6] Foreshew G. A career as an A&E department pharmacist. Hospital Pharmacist 2005;12:61–64

[7] Aiello M, Terry D, Selopal N et al. Examining the emerging roles for pharmacists as part of the urgent, acute and emergency care workforce. Clinical Pharmacist 2017;9(2):56–64. doi: 10.1211/CP.2017.20202238

[8] Pharmacy Research UK. Enhanced clinical pharmacy practice in the emergency department: what is it and what does it mean for patient care — project detail. 2016. Available at: http://pharmacyresearchuk.org/6527-2 (accessed September 2019)

[9] Greenwood D, Steinke D, Tully MP et al. Enhanced clinical pharmacy practice in the emergency department: what is it and what does it mean for patient care? 2018. Available at: http://pharmacyresearchuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Enhanced-clinical-pharmacy-practice-in-the-emergency-department-DGreenwood-VFinal.pdf (accessed September 2019)

[10] ACT Academy. Online library of quality, service improvement and redesign tools: reducing length of stay. 2018 Available at: https://www.improvement.nhs.uk/documents/2126/reducing-length-of-stay.pdf (accessed September 2019)

[11] Pegler S & Robinson S. Reducing the length of hospital inpatient stay: impact on drug expenditure and pharmacy workload. Pharmacy Management 2016;32(1):3–7

[12] Hatton K, Grice K, Morgan L & Wright D. Evaluation of the pharmacist service to the emergency department at a large teaching hospital. In Prescribing and Research in Medicines Management (UK and Ireland) Conference 2016 Health Foundation London January 29th 2016 “Ethics, Economics and the Future of Medicines — A Population Perspective”. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2016;25(S2):12–13. doi: 10.1002/pds.4019