Abstract

Aim: To investigate pharmacy students’ use of, and attitudes towards, Facebook and professionalism.

Design: A quantitative, online anonymous surveySubjects and setting: 91 pharmacy students at a UK university completed the online survey.

Results: Most students completing the survey were female and most had a Facebook account which they logged onto daily. Results suggest pharmacy students need and want more guidance on online professionalism.

Conclusion: Although the sample size of the study is small, the findings are nevertheless interesting and insightful and warrant further investigation. The findings indicate that there is a need for students to be more aware of online professionalism, and that they require clear guidelines on online professionalism. These issues may best be dealt with through their undergraduate education in order to prepare students for their careers as healthcare providers.

Introduction

“The internet blurs the line between what is personal and what is professional, as well as between self-disclosure and transparency”

[1]

The younger generation is growing up online and leaving a digital footprint[2]

. This digital footprint may consist of information and behaviour individuals would not openly share as professionals. There have been reports in recent years in the US, the UK and across Europe of students being disciplined or dismissed as a result of posts on Facebook[3]

. There have also been reports of doctors being declined for positions due to information employers have found on Facebook[4]

. Discussion about the ethics of using social networking sites (SNSs) has started to appear in the lay and academic literature. Research on medical student’s use of SNSs tends to suggest that students do not alter their default privacy settings and therefore their Facebook accounts are accessible to the public. Recently, Finn et al found medical students struggle with negotiating their personal and professional identities both on and offline[5]

.

Research suggests there is a need for students in the professions to be more aware of the potential consequences of making information visible and accessible to the public, and how to be more professional online[6]

. Many students who use Facebook have been found to show little concern about privacy despite knowledge of the privacy settings available[7]

.There have been a number of recent studies conducted in the area of student doctors’ use of SNSs, with many concluding that there is a need for clearer guidelines about online professional behaviour[2],[8],[9]

. These studies also suggest a need for more education for student professionals with regard to e-professionalism, and the impact images and information placed on SNSs such as Facebook can have on their professional reputation and identity. It is also suggested that creating unprofessional content online can reflect poorly on a profession itself[8]

.

With regard to pharmacy students there is a paucity of research in the area of online professionalism and social networking sites. Cain puts forward the notion of e-professionalism and asks whether pharmacy schools in the US should be educating students on the issue of social networking and their future careers as professionals[10]

. Pharmacy organisations are increasingly using social networking sites with the aim of improving both communication and the dissemination of information[11]

. For example the American Pharmacists Association launched a Facebook group in 2008 and to date has over 13,000 followers. The issue of e-professionalism will continue in the digital age as professionals and student professionals increasingly continue to communicate via online networks. This online communication blurs the boundaries between public and private life. In the US Cain et al. developed a 13-item questionnaire for pharmacy students[9]

. The study found that students were opposed to authority figures’ use of Facebook for judgements on character and professionalism. Interestingly, more than half of the pharmacy students in a US study intended to make changes to their online posting behaviour after receiving an e-professionalism education session, highlighting the potential benefits of educating professional students on the issue.

The aim of this study was to gain a deeper understanding of Facebook use and attitudes towards online professionalism and guidance by pharmacy students at one university in the UK.

Methods

An anonymised online survey was devised and emailed to 350 pharmacy students at a UK university. No incentives were offered for the completion of the survey. Question topics included the use of Facebook, privacy settings and online professional behaviours. Results were analysed by SPSS (version 19). Ethical approval was received from the University of Central Lancashire research ethics committee.

Results

In total, 91 students completed the survey (a response rate of 26 per cent). Most participants were female (69 per cent), which reflects the general population of the cohort group and most were in the 21–24 years (42 per cent) and 18–20 years age ranges (36 per cent). With regard to ethnic origin, most described themselves as white British (37 per cent) followed by Indian (28 per cent) and Pakistani (20 per cent). Students who completed the survey were from across all years of study (first year, 30 per cent; second year, 20 per cent; third year, 25 per cent and fourth year 25 per cent).

Most respondents (84 per cent) had a Facebook account, and of those, 78 per cent per cent logged on to Facebook daily. Only 8 per cent of participants used any other social networking site, and only 7 per cent used a professional networking site such as LinkedIn. Most of the students (92 per cent) said they were aware of the privacy settings available on Facebook, with 85 per cent claiming to use these settings to limit public access to their information on Facebook.

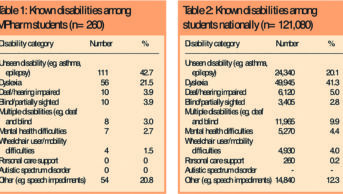

Table 1 shows what information the students had on their Facebook account and what information is available to the public. Most students have their Facebook account listed under their real name (93 per cent) and available to the public (90 per cent). Other information such as photographs, date of birth, contact details and views, although on their Facebook accounts, were not publicly available.

The top three main reasons for using Facebook were to keep in touch with friends (75 per cent), keep in touch with family (45 per cent) and share photos (34 per cent). Fifty-five per cent of respondents said that they were not members of professional pharmacy-related groups on Facebook. A high percentage (40 per cent) had accepted a friend request from someone they did not know well and 26 per cent admitted that they had photographs of themselves on Facebook they found embarrassing.

With regard to professionalism, half (51 per cent) reported that they had seen what they would describe as unprofessional behaviour by their colleagues on Facebook. Most (70 per cent) believed that a student should be accountable for an illegal act discovered through a Facebook posting, and half (52 per cent) thought students should be accountable for unprofessional behaviour discovered through Facebook. Half (51 per cent) believed that the information posted on Facebook affects people’s opinions of them as professional healthcare providers. Just over half (58 per cent) indicated they would continue to have a Facebook account in their name once they qualified as pharmacists, with 28 per cent not sure. Students were asked how much they agreed or disagreed with four statements relating to Facebook, with a particular focus on fitness-to-practise guidance. The statements were adapted from Garner and O’Sullivan’s study of medical students to apply for pharmacy students[12]

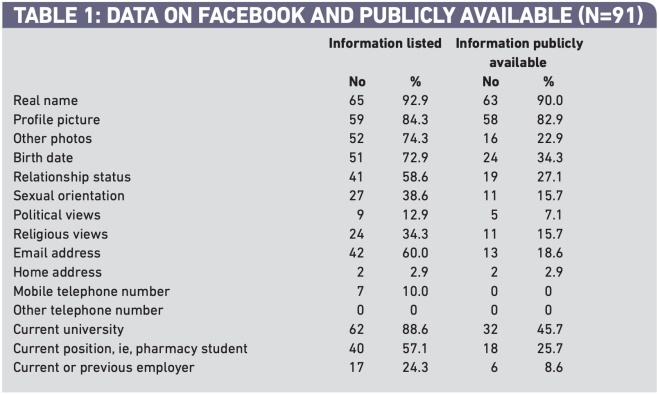

. The responses are presented in Table 2.

Discussion

Our results may appear positive in that pharmacy students are starting to make the information about themselves less available to the public, but it seems they still tend to use their own name and have a profile picture in the public domain. A large percentage of the pharmacy students in the current study also intend to keep their Facebook account once they qualify. The survey showed a large majority of the respondents were aware of the requirements of professional behaviour, with 91 per cent aware of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society fitness-to-practise guidance on personal and professional behaviour, and 95 per cent understanding what the pharmacy school would classify as unacceptable behaviour. Most pharmacy students (83 per cent) agree that what happens outside the university could impact upon their fitness to practise. However, the results suggest a difference of opinion among the students. Although a third of students (33 per cent) disagreed with the statement that “what happens on sites such as Facebook is separate from what happens in University”, half (52 per cent) agreed with the statement. The findings from this study suggest that some students think Facebook is part of their private lives and therefore separate from their professional lives. This suggests that students need to be more aware that information made public online via SNSs such as Facebook could impact on their careers.

Interestingly a large percentage (68 per cent) of the pharmacy students in the current study want to see more guidelines on online professionalism. Respondents could express any opinions and comments in a free text box at the end of the survey. Thirteen did so. Two main themes were apparent from the comments: that students think their Facebook account is separate from their professional life and career, and that guidance is needed. For example:

- Professional guidance is desperately needed in this increasingly used arena. I will probably not use Facebook at all as a pharmacist unless I have clear guidance from my governing body.

- Facebook is a very personal matter for many people where they are free to share extensive information about their lives. For employers/university to expect perfection and professionalism from these people at all times is unrealistic.

- The implications of what happens on Facebook should be highlighted to students studying any medical degree during their inductions. Examples should be highlight to ensure they understand the serious consequences that could occur.

Conclusion

Although the sample size is small, the findings are interesting and insightful and warrant further investigation. In October 2011, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society issued guidance encouraging pharmacists to “use social media and social networking responsibly and with the same high standards that they would apply in real world interactions”[13]

. Our findings indicate that there is a need for students to be more aware of online professionalism, and that they require clear guidelines on online professionalism. These issues may best be dealt with through their undergraduate education in order to fully prepare students for their careers as healthcare providers.

About the authors

Julie Prescott, PhD, is research associate, Sarah Wilson, PhD is lecturer in social pharmacy and Gordon Becket is professor of pharmacy practice at the University of Central Lancashire School of Pharmacy.

Correspondence to: Julie Prescott (email: jprescott@uclan.ac.uk)

Acknowledgements

We thank the School of Pharmacy and Biomedical Sciences at the University of Central Lancashire for its funding support for this project.

References

[1] Zur O, Williams MH, Lehavot K et al. Psychotherapist self-disclosure andtransparency in the Internet age. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 2009;40:22–30.

[2] Mostaghimi A & Crotty BH. Professionalism inthe digital age. Annals of Internal Medicine 2011;154:560–562.

[3] Read B. Think before you share. Students’online socialising can have unintended consequences. Chronicles of Higher Education 2006;52:38–41.

[4] Du W. Job candidates getting tripped up by Facebook. 2007. Available at: www.msnbc.msn.com/id/20202935/ (accessed 9 February 2012).

[5] Finn GF, Garner J & Sawdon M. “You’re judged all the time!” Students’ views onprofessionalism: a multicentre study. Medical Education 2010;44:814–825.

[6] Gross R & Acquisti A. Information revelationand privacy in online social networks (theFacebook case). ACM Workshop on Privacy in the Electronic Society (Alexandria, VA, 2005), ACM Press.

[7] Jones H, Soltren JH. “Facebook: threats to privacy”. Project MAC: MIT Project on Mathematics and Computing 2005. Available at: http://www-swiss.ai.mit.edu/6.805/student-papers/fall05-papers/facebook.pdf (accessed February 2012).

[8] Greysen SR, Kind T & Chretien KC. Onlineprofessionalism and the mirror of socialmedia. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2010;25:1227–1229.

[9] Cain J, Scott DR & Akers P. Pharmacy students’Facebook activity and opinions regardingaccountability and e-professionalism. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 2009;73(6):1–6.

[10] Cain J. Online social networking issueswithin academia and pharmacy education. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 2008;72(1):1–7.

[11] Mattingly JT, Cain J & Fink JL. Pharmacists on Facebook: online social networking and theprofession. Journal of the American Pharmacist Association 2010;50:424–427.

[12] Garner J & O’Sullivan H. Facebook and theprofessional behaviour s of undergraduatemedical students. The Clinical Teacher 2010;7:112–115.

[13] Social media and social networking. Professional support bulletin no 7. The Pharmaceutical Journal 2011;287:508.