Abstract

Aim

To assess the appropriateness of prescriptions for tramadol hydrochloride and associated adverse effects.

Design

A quantitative, cross sectional survey.

Subjects and setting

The inclusion criteria included patients over the age of 65 years who had received a prescription for tramadol in the previous six month period. Patients were selected from three general practices using the Egton Medical Information System (EMIS) search facility. In total 222 patients were reviewed.

Results

Tramadol was shown to be prescribed in older patients. It is used for the management of pain for a range of indications although not always following expert pain management guidelines. Tramadol is associated with a wider range of adverse affects than are other weak opioids. Although no direct correlation could be made to the prescribing of tramadol, patients in this sample experienced adverse effects, including falls, while using tramadol or other concomitant treatments. Patients in the survey sample had a significant renal deficit and were taking numerous concomitant and potentially interacting medicines. The survey demonstrated a link between increasing concomitant medication and the occurrence of adverse effects.

Conclusion

The use of tramadol in older patients should be reviewed. Although there is no doubt that tramadol is an effective agent for treating mild to moderate pain it is associated with a range of adverse effects which have the potential to cause significant morbidity. There is no evidence to suggest that tramadol is any more effective than other weak opioids in the management of pain and, when considering the adverse effect profile and added cost of prescribing in comparison with codeine phosphate, its place in therapy is questionable.

Tramadol hydrochloride is an opioid analgesic used for the treatment of moderate to severe pain. It has been shown to have equal efficacy to that of other weak opioids such as dextropropoxyphene or codeine used alone or as co-codamol 30/5001 in short-term studies of chronic pain or osteoarthritis.

Opioid analgesics can be used alone or in combination with non-opioid analgesics for the treatment of moderate to severe pain. Weak opioids, including tramadol, are included at Step 2 of the World Health Organization Analgesic Ladder2 after the use of non-opioid analgesics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs at appropriate doses has failed to produce a sufficient response. Although the effectiveness of opioids in the treatment of pain is well established they can, in relatively small doses, cause constipation, nausea, vomiting and drowsiness. Pharmaceutical companies have prioritised the development of drugs which maintain an analgesic effect comparable to that of traditional weak opioids while avoiding the complicating adverse effect profile. Tramadol is one such agent and it has been available in the UK since 1994. Tramadol is indicated and effective in the treatment of moderate to severe pain3 but not effective for severe pain, when stronger opioids should be used.4,5

Tramadol exerts its effect via two mechanisms. First, it shows a weak affinity for mu-opioid receptors involved in the transmission of pain, hence its classification as a weak opioid.6 Secondly, tramadol inhibits the reuptake of noradrenaline and of serotonin while also enhancing the release of serotonin.7,8 Both transmitters are involved in the inhibition of the response to noxious stimuli within the central nervous system. The increased levels of noradrenaline and serotonin in the synapse alter nociceptive signalling pathways and so result in an analgesic effect.

Tramadol is readily absorbed after oral administration independent of whether food is present9 and undergoes first-pass metabolism in the liver. The absorption of tramadol is over 85 per cent with an absolute bioavailability of between 65 and 70 per cent; the difference in these figures is attributed to the fact that there is a 20 to 30 per cent first-pass effect. The metabolism of tramadol is mediated by the cytochrome P450 (CYP450) system and in particular the CYP2D6, CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 isoenzymes.7,10,11 The drug is metabolised by O- and N-demethylation proceeding to form glucuronide and sulphate conjugates.7 Mono-O-desmethyl tramadol (M1) is the most active metabolite, with about 200 times stronger affinity for the mu-opioid receptors than tramadol. Around 90 per cent of the administered dose is excreted in urine as metabolites via the kidneys12 with an elimination half life of about six hours. The half life remains roughly constant regardless of acute or chronic administration. The dependence on renal excretion as the main route of elimination of tramadol and its metabolites is a significant issue in relation to elderly patients with declining renal function and extensive co-morbidity.

Despite the initial marketing claims made for tramadol, postmarketing surveillance suggests that it does exhibit a significant adverse effect profile typical of an opioid analgesic.13 Dizziness and nausea are the most commonly reported effects in around 10 per cent of cases.

One of the most troublesome and dose limiting effects of weak opioids is constipation, particularly in the elderly. Tramadol was initially promoted as causing less constipation but reports suggest it is an issue for anything between 1 and 10 per cent14 of patients. Hallucinations, convulsions and confusion have all been reported at therapeutic doses as have very rare cases of dependence and withdrawal-like syndrome. In 1996, the Committee on Safety of Medicines issued guidance to suggest that tramadol should be used for short-term or intermittent treatment only. It should not be used in patients with a history of dependence, or those prone to seizures or using drugs which lower the seizure threshold.13

There is little convincing clinical evidence to suggest that tramadol is more effective than other weak opioid analgesics. Although extrapolation of data obtained from patients with specific types of pain, such as post surgical, cancer pain or from single dose studies is not necessarily reliable, the data seem to suggest that tramadol is no more effective than other weak opioids. When considering this, the potential adverse effect profile and additional prescribing costs of tramadol its routine use for pain control should be questioned.

Methods

This survey was conducted in collaboration the local primary care trust, and ethical clearance was not deemed necessary.

Three general practices from within the PCT area were randomly identified to be included in the survey; they were designated practice 1 (7,502 patients), practice 2 (5,299 patients) and practice 3 (6,470 patients).

Patients were selected from each practice using the EMIS computer system search facility. All patients over the age of 65 years who had received a prescription for tramadol hydrochloride in the preceding six-month period were included. This was independent of the duration of prescribing before the point of issue of the last prescription.

Age, sex, indication for use, dosage and eGFR were recorded recorded for all patients in relation to tramadol. Data were considered for each practice and collectively as a whole.

Patients’ records were examined to identify concomitant medicines that could cause an adverse effect when taken with tramadol. To focus the search the following therapeutic classes were included: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, other antidepressants, hypnotics, antiepileptic drugs, other opioids and anxiolytics.

A list of “other medication” was created if a particular drug with the potential to interact with tramadol but did not fit into the above therapeutic classes appeared in the prescription record.

Any adverse effects reported by patients were recorded, in particular, the incidence of falls. Where possible this also included the side effects reported when patients were taking other weak opioids either before or after tramadol.

Results and discussion

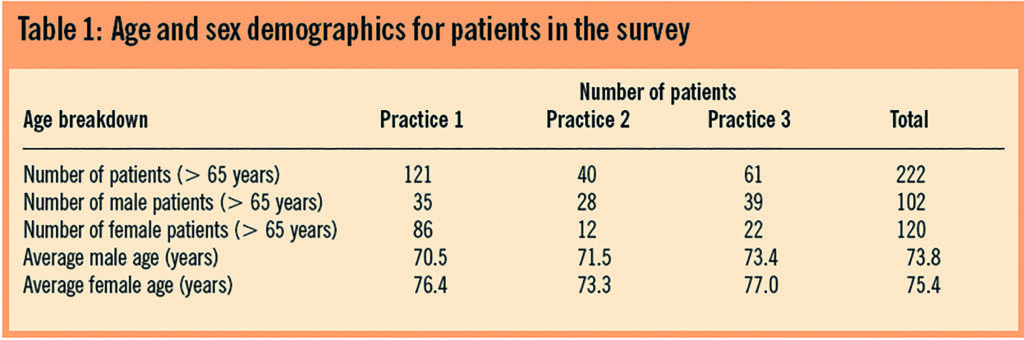

The survey included 222 patients from three NHS general practices. The age/sex demographic is shown in Table 1.

Practice 1 accounted for 121 (55 per cent) of the sample, practice 2, 40 (18 per cent) and practice 3, 61 (27 per cent). In terms of the overall size of the practice in relation to the number of patients prescribed tramadol practice 1 comprised 0.05 per cent of the overall practice population, practice 2, 0.007 per cent and practice 3, 0.009 per cent.

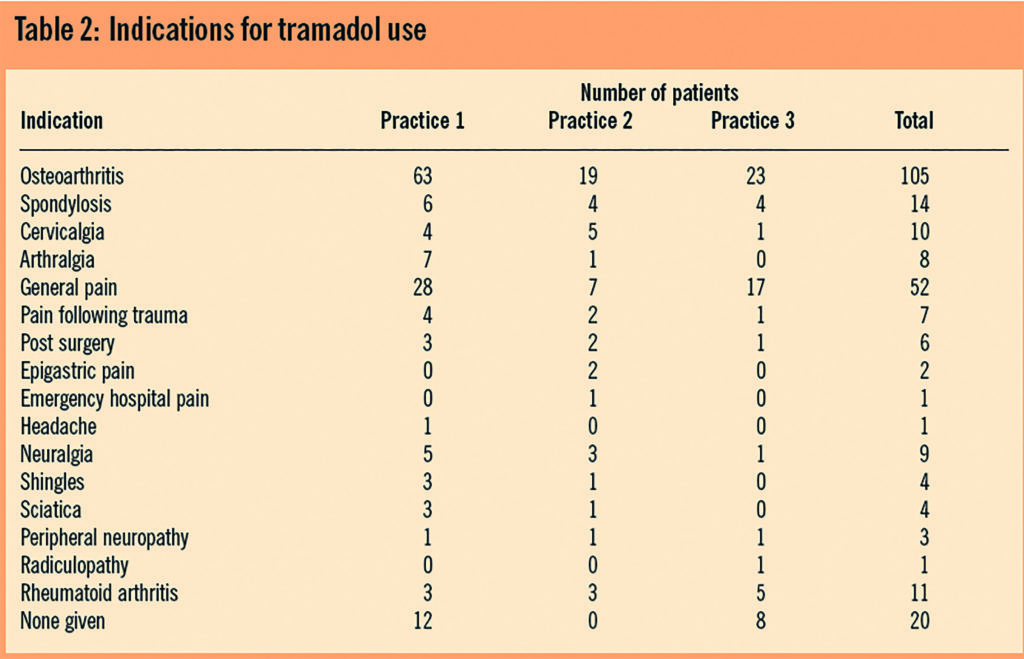

Indication for use is shown in Table 2; the information collected from patients’ notes in some instances gave more than one indication for the prescription of tramadol. As such the totals in Table 2 do not directly tally with the number of patients reviewed. The total number of indications is shown as was recorded in the patients’ clinical record. This was thought to be an appropriate strategy, bearing in mind that the clinical decision to prescribe tramadol could well be influenced by a patient presenting with more than one source of pain. In some instances the clinical record did not specify the exact diagnosis and these patients were grouped under the heading of general pain.

Tramadol was prescribed to treat the pain associated with numerous conditions. The BNF indicates the use of tramadol for the management of moderate to severe pain.4 Because pain can be a symptom of numerous conditions, this indication is open to interpretation since the only criteria are the level of pain that the patient is in and the patient’s own perception of its severity. We can classify pain in terms of the associated pathology as in Table 2 to allow us to comment on the appropriateness of use. Clearly this is subject to patient-based variation and individual clinical judgement but nevertheless should comply with generally accepted good practice and expert opinion.

The most frequent indication for the use of tramadol was osteoarthritis (OA) both in the combined group, 105 (53.1 per cent), and the individual surgeries, 63 (55.9 per cent), 19 (55.8 per cent) and 23 (44.4 per cent) for practices 1, 2 and 3, respectively. The BNF states that pain associated with OA and soft-tissue disorders should be treated following the WHO guidelines; tramadol has its place in these guidelines for moderate pain. Various studies have shown that tramadol has produced a significant decrease in pain and symptoms such as disturbed sleep and limitation in movement associated with OA when treated with tramadol.15–23

General pain was the second largest indication in this study used for 69 (26.4 per cent) patients overall, and 36 (25.2 per cent), 14 (25.0 per cent) and 19 (30.2 per cent) for the three practices, respectively. Different patients will have differing pain thresholds and respond differently to analgesics, making treatment difficult to regiment. However, when considering the types of pain classified in this group such as post-surgical, trauma, headache and the overall general pain class, it is questionable as to why tramadol has been chosen. It is likely for example that post-surgical pain is treated with a standard set of discharge medicines and the patient instructed to use the tramadol if pain worsens. The use of the drug in this instance rather than codeine is highly questionable based on accepted evidence that tramadol shows no clinical superiority to other weak opioids.1

During the survey we discovered that 20 patients (7.8 per cent) had no record of a specific indication for the use of tramadol although some assumptions could have been made where the co-morbidities were noted. Practice 2 was the only practice to have an indication noted for all patients who were being prescribed tramadol, 12 (8.3 per cent) patients in practice 1 and eight (12.7 per cent) in practice 3 had no indication noted. For this group of patients it is impossible to assess the appropriateness of prescribing based on the information available. Incomplete information in clinical notes can result in difficulties when carrying out medication reviews, particularly if the initiating prescriber is not carrying out the review.

Neuropathic pain, comprising neuralgia, shingles, sciatica, peripheral neuropathy and radiculopathy, represented the smallest group of patients being prescribed tramadol. The total number of patients overall for this group was 21 (8.1 per cent) and, individually, practice 1, 12 (8.4 per cent), practice 2, six (11.5 per cent) and practice 3, three (4.8 per cent).

Neuropathic pain is notoriously difficult to treat not least because the drugs used as first line treatment, such as tricyclic antidepressants and antiepileptic drugs, are associated with adverse effects that can seriously limit their use and the tolerable effective dose prescribed. The Cochrane Library includes a systematic review on tramadol and its use in neuropathic pain as an alternative to the conventional treatments. It concludes that there is a place for tramadol in the treatment of neuropathic pain and that it displays efficacy similar to that of tricyclic antidepressants and anticonvulsants. It was acknowledged that adverse effects were also present when using tramadol but that they were more tolerable than those associated with tricyclic antidepressants and anticonvulsants, and that they are reversible on ceasing treatment.24 Although this evidence supports the use of tramadol in this instance, care should be taken when combining other medicines with tramadol that are likely to alter its elimination, reduce seizure threshold or increase drowsiness. Patients being treated for neuropathic pain are likely to be taking such concomitant medication.

Rheumatoid arthritis was indicated in 11 (4.3 per cent) patients, comprised of practice 1, three (2.1 per cent), practice 2, three (2.1 per cent) and practice 3, five (7.9 per cent). Rheumatoid arthritis is an inflammatory condition associated with the immune response and as such its mainstay of pain relief is with NSAIDs alongside control of the underlying condition with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs).4 There is no evidence to suggest that tramadol has any anti-inflammatory activity and so the use of it in treating the pain associated with RA is questionable. The use of tramadol as an analgesic for RA patients is acceptable, notwithstanding the fact that evidence suggests it shows no superiority to other weak opioids.1

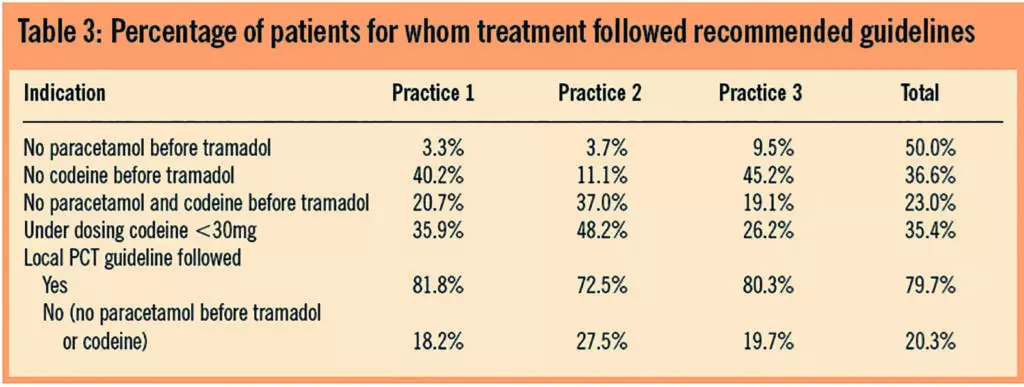

As well as the indication for use, the prescribing patterns of tramadol were reviewed in terms of how patients’ pain had been treated in relation to the WHO and local PCT pain guidelines. This is of significant interest in terms of how frequently patients are started on the drug first line or without having used appropriate dosages of drugs indicated at a lower stage of the guideline for a reasonable time period. Table 3 shows these prescribing patterns.

Local guidelines require that paracetamol is used first-line at a regular dose of 1g four times daily to treat pain. Also included is the option to introduce tramadol 100mg four times daily or codeine phosphate at step 2 when paracetamol alone has failed. It is accepted that neither the WHO nor local pain guidelines differentiate the weak opioid group in terms of stating which individual drugs should be used first after an appropriate consideration has been given at step 1. However, evidence already discussed clearly suggests that codeine and tramadol are of equal efficacy, the use of tramadol shown in Table 3 either before paracetamol or codeine at an appropriate dose is questionable.

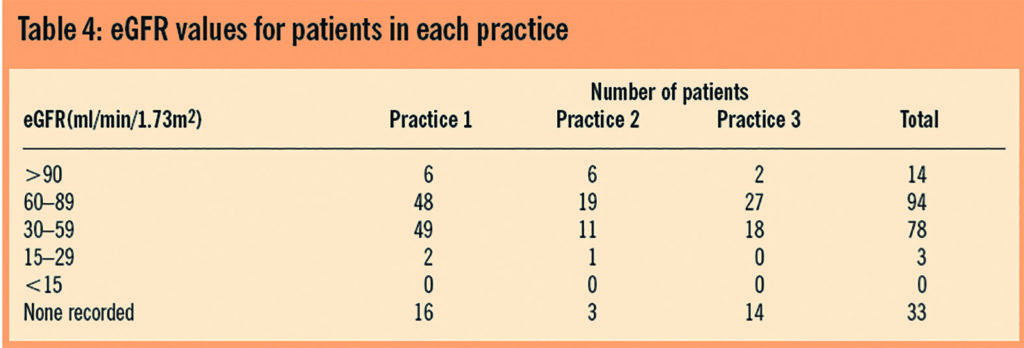

With reference to the adverse effect profile of tramadol, and considering the pharmacokinetics of the drug, the renal function of patients could be of particular importance when making a prescribing decision. As such the last available eGFR reading for each patient was recorded to observe the range of renal function within the sample and potentially identify those patients where renal function may not be adequate. Table 4 shows the distribution of patients through the range of eGFR. Normal renal function is classified as being in the range 60–200ml/min/1.73m2, below this level there is a possibility of impaired clearance of drugs. This is of particular importance with drugs such as tramadol which are excreted as active metabolites.

In total 81 patients (36.5 per cent) fell below the bottom threshold of the normal renal function range. A significant number had no reading recorded in their notes and as such could have contributed further to the size of this group.

Reduced renal function results in the active M1 metabolite accumulating, extending the half-life up to two-fold necessitating potential dosage adjustment or increasing dosage interval25. In patients with end stage renal function and an eGFR of below 15ml/min/1.73m2 the dose of tramadol should not exceed 50mg every 12 hours.26 The summary of product characteristics for Zamadol 50 capsules26 suggests that patients with creatinine clearance of less than 30ml/min should be the subject of dosage adjustment.

At therapeutic doses tramadol has been shown to cause less respiratory depression than the traditional opioid analgesics; however as the M1 metabolite accumulates it may exceed the therapeutic plasma concentration and cause adverse effects. Barnung et al27 support this theory. They reported that an elderly male (75 years) with impaired renal function received 100mg tramadol four times a day and suffered from severe respiratory depression but suffered no adverse effects with a dose of 100mg three times a day. This clearly indicates the dose-response relationship of tramadol affects both the adverse effects and the analgesic effect. This is an individual case report and as such does not generalise to the population at large. Raffa et al28 also found that patients with a creatinine clearance of less than 80ml/min displayed a decreased rate and extent of excretion of the active M1 metabolite.

Accumulation of pharmacological agents has implications in treating older people, potentially increasing adverse effects. As one of the adverse effects of tramadol is drowsiness there is a likelihood of older people falling, causing injuries that impact on their mobility and subsequent health.29 Turnheim30 suggested that all elderly patients should be treated as having renal impairment due to the decline in renal function being directly related to the incidence of adverse drug reactions in the older patient. Dosing of tramadol in older patients should reflect their physiological changes, it is recommended that the dose of tramadol is started low (50mg) and titrated upwards until an analgesic level is found that does not cause adverse effects, the option of increasing the dosage interval could also be considered. Clearly this is not only an issue affecting tramadol. All other weak opioids should be prescribed with care in patients with a significant renal deficit.

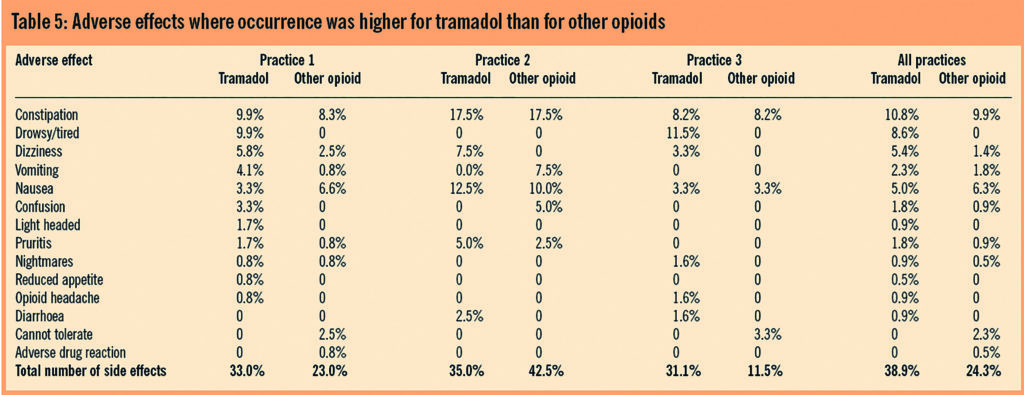

Table 5 shows the percentage of patients in terms of the whole sample reporting individual side effects with tramadol and with other weak opioids, per practice and as a whole. The reference to an ADR in the Table is following a documented report by the medical practitioner which was recorded in notes as such.

Drawing a definitive conclusion or statistical relationships from this Table is difficult because the number of patients reporting adverse effects has not been quantified in terms of the number of prescriptions issued for each group. It is true to say that patients have clearly experienced a range of adverse effects from tramadol which appears to be greater than that experienced from using other opioids. It is significant that these data are similar across the three practices and are not limited to one practice. In particular the occurrence of constipation from our sample is consistent with and similar to that from other opioids.

The lack of or low incidence of recording for drowsiness, sedation or confusion for the other opioids group seems to be anomalous. All opioids cause drowsiness and sedation and so the lack of reporting of such affects for opioids other than tramadol found in this survey should be viewed with caution. The adverse effects for tramadol across all three practices were, in percentage terms, similar although significant variation was demonstrated for the other opioids group. This raises the question of possible elevated awareness among the prescribers in terms of recording adverse effects reported for tramadol.

Polypharmacy is an issue with this group of patients owing to their advancing age, and associated co-morbidity evidence of significant drug-related hospital admission has been demonstrated in the literature.31 Patients were found to be taking multiple medicines, some of which clearly had the potential to interact with tramadol. These interactions may cause similar adverse effects to that of tramadol such as drowsiness, sedation, confusion, decreased mental and cognitive function, antimuscarinic effects, including constipation, reduction in seizure threshold, nausea, vomiting and dizziness with varying degrees of severity.

Some specific problems can occur with some drugs and use with tramadol should be avoided if possible or an alternative analgesic used. Tricyclic antidepressants, antihistamines, neuroleptics, anxiolytics and hypnotics are CNS depressants and increase the risk of enhanced sedation or respiratory depression. SSRIs have the potential to cause serotonin syndrome and inhibit the isoenzyme CYP2D6, which is responsible for the metabolism of tramadol. Tricyclic antidepressants and neuroleptics increase the risk of CNS toxicity and convulsions by lowering the seizure threshold while carbamazepine reduces the effect of tramadol as it is an enzyme inducing drug.

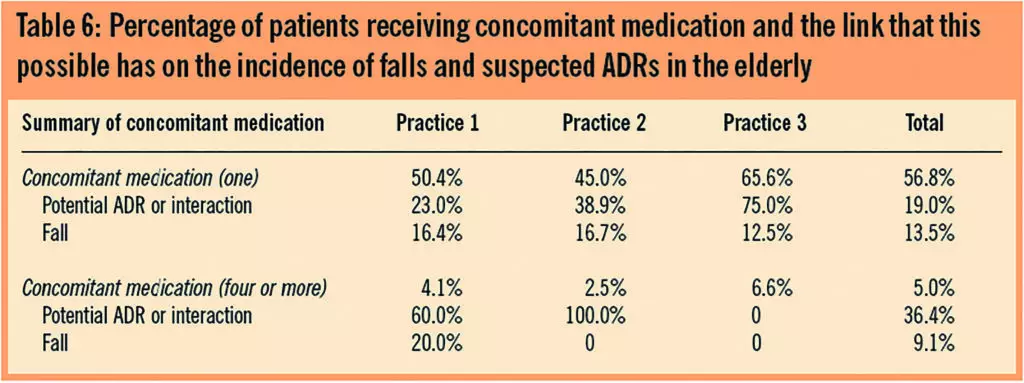

Table 6 shows the percentage of patients who took either one concomitant medicine or four or more and the potential ADRs or falls as a percentage of that group. This delineation was agreed in line with the National Service Framework for Older People, which suggests that older patients should be maintained, where possible, on a gold standard of four medicines or less in order to reduce adverse effects and the potential for drug interaction.32 This framework also states the important of avoidance of falls in elderly patients particularly in the context of medication-related falls. An attempt is made to examine the relationship between increasing number of concomitant medication and potential adverse events.

Table 6: Percentage of patients receiving concomitant medication and the link that this possible has on the incidence of falls and suspected ADRs in the elderly

The information shown in Table 6 is influenced by a range of factors other than simply interaction between medicines. As has been discussed, renal function could play a part but other significant factors such as living conditions and social support networks clearly influence how a patient can manage the daily activities. No firm conclusions can be reached from the data in this table but a potential association between increased concomitant medication and increased incidence of both ADRs and falls may warrant further investigation.

Conclusion

Evidence suggests that tramadol is an effective analgesic, equivalent in efficacy to other weak opioids such as codeine phosphate. However, tramadol demonstrates a range of adverse effects that have the potential to cause problems in a group of older patients. In many cases the data collected do not allow for absolute conclusions in terms of the level of adverse effects reported or the subsequent results of those adverse effects. What can be said from the results is that tramadol appears to cause adverse effects to a greater extent than other weak opioids. This conclusion could be further investigated to establish firm links and possible statistical significance.

The prescribing patterns observed in the survey suggest that tramadol is being used as an analgesic before other options have been suitably exhausted. In some case it is being used as a first-line treatment without any attempt to follow expert pain management guidelines. Case note review demonstrates that a proportion of prescribing is evidence- or guideline-based, while the remaining cases do not indicate any observed rationale for choice or use, or have circumvented important stages of the guidelines or accepted practice as to which drugs should be used first-line.

This survey demonstrates the drug is regularly being prescribed in older patients, most of whom have significant co-morbidity and concomitant therapy. Tramadol has been proven to cause a range of adverse effects not observed before marketing and many of these effects could contribute to significant morbidity, particularly as a consequence of falls.

This survey cannot be extrapolated to the general population of the UK. However, it does demonstrate a pattern of prescribing that may well be observed in other GP practices, namely, tramadol is prescribed where other equally effective but safer options exist.

Prescribing should be reviewed in order to ensure that appropriate pain relief is given to patients following evidence-based guidelines. Clearly the equal efficacy, relatively severe adverse effect profile and added cost of tramadol should call into question its routine use for pain control in elderly patients.

About the authors

Andrew K. Husband, MSc, MRPharmS, is principal lecturer — pharmacy practice, at the University of Sunderland, Faculty of Applied Sciences, Pasteur Building, Wharnecliffe Street, Sunderland SR1 3SD, where Barbara Heron was previously a final-year MPharm undergraduate.

Anne-Marie Bailey, DipClinPharm, MRPharmS, is a prescribing adviser at NHS South of Tyne and Wear.

Correspondence to: Mr Husband (e-mail andrew.husband@sunderland.ac.uk)

References

- National Prescribing Centre. The use of strong opioids in palliative care. MeRec Bulletin. No 22.2009.

- WHO analgesic ladder. Available at: www.mydr.com.au/ content/images/categories/cancer/WHO_Analgesic_ladder.gif (accessed 28 January 2009).

- National Prescribing Centre. The use of strong opioids in palliative care. MeRec Briefing. No 22.June 2003.

- British National Formulary. London: British Medical Association and Royal PharmaceuticalSociety of Great Britain, 2008.

- National Prescribing Centre. The withdrawal of co-proxamol: alternative analgesics for mild tomoderate pain. MeRec Bulletin 2006;16(4).

- William HJ. Tramadol hydrochloride. Something new in oral analgesia. Current TherapeuticResearch 1997;58:215–26.

- Grond S, Sablotzki A. Clinical pharmacology of tramadol. Clinical Pharmacokinetics2004;43:879–923.

- Shipton EA. Tramadol-present and future. Anaesthetic Intensive Care 2000;28:363–74.

- Liao S, Hills J, Stubbs RJ, Nayak RK. The effect of food on the bioavailability of tramadol.Pharmaceutical Research 1992;9:308

- Raffa RB, Friderrichs E. The basic science aspect of tramadol hydrochloride. Pain Reviews1996;2:249–71.

- Analgesics, antidepressants, antiepileptics and anxiolytic sedatives hypnotics andantipsychotics. Martindale 32nd Edition. London: Pharmaceutical Press.

- Broadbent A, Khor K, Heaney A. Palliation and chronic renal failure: opioid and other palliativemedications — dosage guidelines. Progress in Palliative Care 2003;11:183–190.

- In focus — tramadol. Current problems in pharmacovigilance 1996;22:11.

- Summary of Product Characteristics. Zydol 50mg capsules. Available at: www.medicines.org(accessed 2 February 2009).

- Edwards JE, McQuay HJ, Moore RA. Combination analgesic efficacy: individual patient datameta-analysis of single dose tramadol plus acetaminophen in acute postoperative pain. Journalof Pain and Symptom Management 2002;23:121–30.

- Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Single-patient data meta-analysis of 3,453 postoperative patients: oraltramadol versus placebo, codeine and combination analgesics. Pain 1997;69:287–94.

- Rauck RL, Ruoff GE, McMillen JI. Comparison of tramadol and acetaminophen with codeine for long term pain management in elderly patients. Current Therapeutic Research 1994;55:1417–31.

- Katz WA. Pharmacology and clinical experience with tramadol in osteoarthritis. Drugs 1996;52:39–47.

- Roth SH. Efficacy and safety of tramadol HCl in breakthrough musculoskeletal pain attributed to osteoarthritis. Journal of Rheumatology 1998;25:1358–63.

- Malone H, Coffiner M, Sonet B, Sereno A, Vanderbist F. Efficacy and tolerability of sustained-release tramadol in the treatment of symptomatic osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: a multicenter randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clinical Therapeutics 2004;11:1774–82.

- Burch F, Fishman R, Messina N, Corser B, Radulescu F, Sarbu A, et al. A comparison of the analgesic efficacy of tramadol contramid OAD versus placebo in patients with pain dxue to osteoarthritis. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2004;34:328–38.

- Freye E, Levy JV. The effects of tramadol on pain relief, fast EEG-power spectrum and cognitive function in elderly patients with chronic osteoarthritis. Acute Pain 2006;8:55–61.

- Xiang J, Siccardi M, Janagap C, Vorsanger G. Effects of extended-release tramadol on osteoarthritic pain in the elderly. Journal of Pain 2007;8(Suppl):S37.

- Hollinhead J, Dihmke RM, Cornblath DR. Tramadol for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006;3:CD003726.

- Mercadante S, Arcuri E. Opioids and renal function. Journal of Pain 2004;5:2–19.

- Summary of Product Characteristics. Zamadol Capsules 50mg. Available at www.medicines.org.uk (accessed 10 May 2009).

- Barnung SK, Treschow M, Borgbjerg FM. Respiratory depression following oral tramadol in a patient with impaired renal function. Pain 1997;71:111–2.

- Raffa RB, Nayak RK, Liao S, Minn FL. The mechanism(s) of action and pharmacokinetics of tramadol hydrochloride. Reviews in Contemporary Pharmacotherapy.1995;6:485–97.

- Health Education Authority. Older people — older people and accidents. Fact Sheet 2. London: HEA, 1999.

- Turnheim, K. Drug therapy in the elderly. Experimental Gerontology 2000; 39:1731–8.

- Col N, Fafanle JE, Kronholm P. The role of medication in non-compliance and adverse drug reactions in hospitalisations of the elderly. Archives of Internal Medicine 1990;150:841–5.

- Department of Health. National Service Framework for Older People. London: Department of Health, 2001.

This original paper can be read as a PDF (230K) file