Introduction

Over the past 40 years there has been significant development in clinical pharmacy in UK hospitals and the Government has published a number of documents supporting the pharmacist’s clinical role.[1],[2],[3]

The recognition of the importance of the clinical pharmacist has assumed that the pharmaceutical care provided during patient hospital stays helps reduce risk and costs associated with errors and improves outcomes, particularly those associated with medication-related issues.[4]

However, although many hospital pharmacists undertake a significant amount of practice research that shows the impact of the clinical pharmacy service on the quality of patient care, much of it is unpublished and retained locally, therefore, the evidence in the UK continues to be relatively weak.

Prescribing errors pose a threat to hospital inpatients, leading to increased morbidity, mortality and an increased economic burden to health services.[5]

In the UK the rate of prescribing errors varies widely, ranging from 0.3 per cent to 39.1 per cent of medication orders written for hospital inpatients and from 1 per cent to 100 per cent of hospital admissions.[6]

Pharmacy research has shown that prescribing on admission to hospital often contains inaccuracies that can result in patient harm, with potentially serious effects and increased risk of illness.[7],[8],[9]

Medication errors range from those with serious consequences to those that have a relatively minor impact on the patient. Therefore, the severity as well as the frequency of errors needs to be assessed.

The Nuffield Trust, an independent health charity, recently published figures showing that admissions to hospitals have risen by almost 12 per cent over the past five years, with emergency admissions now making up 35 per cent of all hospital admissions in England.[10]

This situation has led to the redesign of the emergency portal in many hospitals as a single emergency assessment unit (EAU) for all medical and surgical patients.

At the Royal Wolverhampton Hospital NHS Trust there is a single EAU, but it excludes children, orthopaedics and head injuries.

Winter pressures and a continuous need for beds at the trust mean that our EAU has a fast turnover, with 75 per cent of patients being assessed, transferred to a ward or discharged home within 24 hours.

With the staff working under such constant pressure it is not surprising that there is an increased risk of prescribing errors.[7]

Thus the emergency assessment unit is one of the main areas within the hospital where pharmacists can contribute to patient care.[11]

The impact of pharmacist involvement on prescribing and management of prescribed medicines on admissions units has been shown in a number of studies.[11],[12],[13]

However, there has been criticism that although studies have attempted to measure the benefits of pharmacist input on the emergency assessment unit, they have been few and limited in scope, and conclusions were more often drawn in terms of pharmaceutical input than in benefit to patient care.[6]

This study sets out to evaluate how pharmacist involvement enhances patient care by reducing potential risk in relation to medication-related issues. The objectives of the study were to determine:

- The number and type of prescribing errors per hospital admission

- The number of pharmacist interventions made in a representative sample of patients seen in the EAU

- The impact of the pharmacist’s intervention

- The number of interventions generated by prescribing errors as opposed to those generated by pharmaceutical care issues

- The main therapeutic groups of medicines requiring pharmacist interventions

Method

On a normal day at the trust, the admitting doctor sees patients who arrive at the EAU after referral by the walk-in centre, the accident and emergency department or a GP. The admitting doctor, after the initial assessment, takes a drug history from the patient normally based on either patient recall or the medicines that the patient has brought in. It is rare for GPs to write a referral letter that includes medication details and when they do these are often inaccurate.

The admitting doctor then writes a drug chart for each patient and, after this, the pharmacist examines the chart to ensure the medicines it outlines are safe, appropriate and cost-effective and to initiate the supply of any medicines not stocked on the ward.

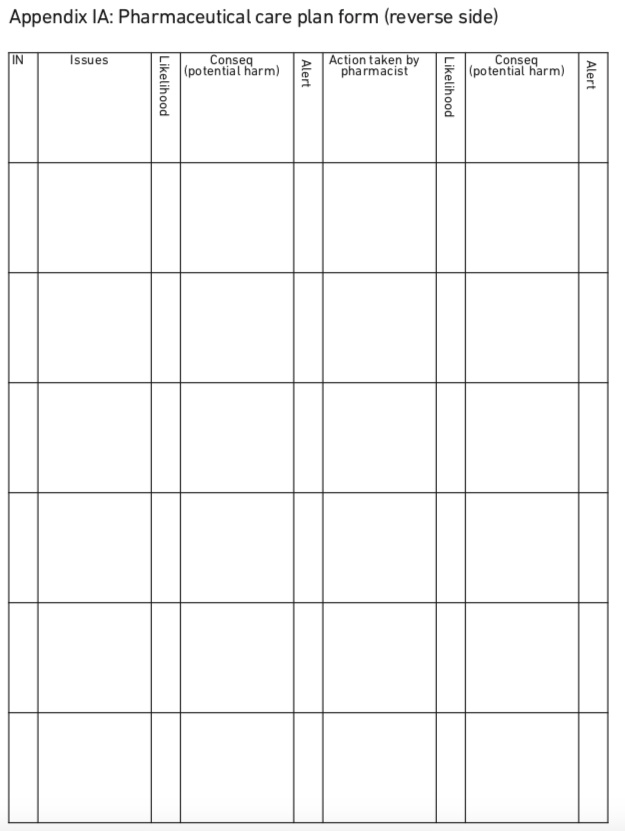

In order to evaluate the quantity, quality and clinical impact of pharmacist interventions, a pharmaceutical care plan form was developed and completed for each patient entering the study, whether or not the pharmacist had intervened (see Appendix I-IA).

Appendix IA

This plan contained all relevant clinical information and the investigator pharmacist recorded any possible drug-related issues and any action taken or suggested.

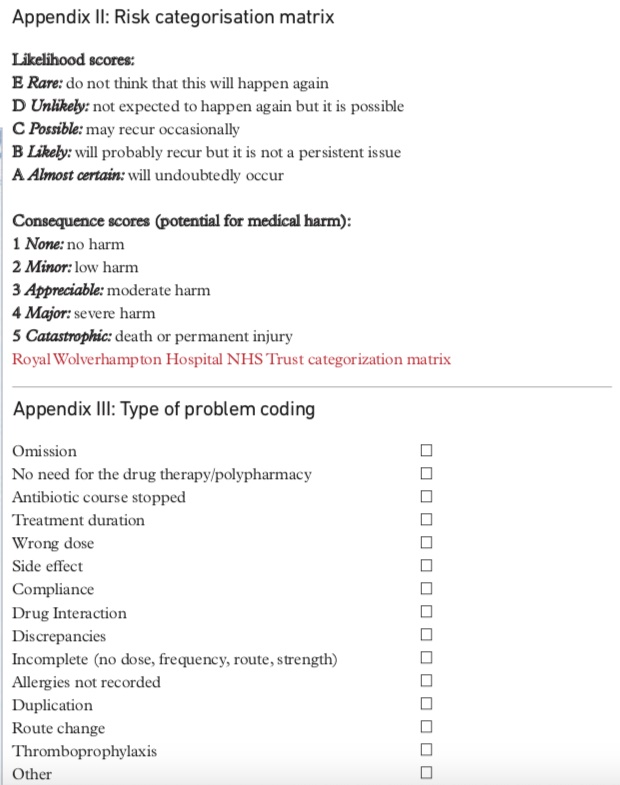

Each medication issue was risk rated according to its potential to cause medical harm using the trust categorisation matrix, which assesses the likelihood of recurrence and the potential consequences if it was not corrected (Appendix II).This risk rating was carried out before and after the pharmacist had intervened.

Appendix II & III

The trust categorisation matrix is a validated method adapted from the one used by the National Patient Safety Agency to assess critical incidents. It produces a colour-coded, traffic-light alert system for each issue depending on the risk of harm.

The colours resulting from the assessment range from green (low), yellow (moderate), amber (high) or red (serious). Using this method the investigator was able to compare the risks for each medicine-related issue before and after intervention.

A problem coding form with a list of possible issues with potential to cause medical harm was developed to facilitate the analysis of the types of interventions (Appendix III).

To prevent operator bias the lead consultant for the unit and a senior pharmacist with a high level of clinical experience assessed the pharmacist’s interventions independently. The assessing pharmacist and doctor undertook their assessments using the same risk categorisation matrix independently and each was blinded to the other’s assessment.

The impact of pharmacist intervention was assessed by calculating the intervention rate, or number of interventions made per individual hospital admission, and whether the assessors considered the intervention to be necessary.

If the assessors considered the intervention to be unnecessary it was recorded as having no potential for medical impact.

Minor interventions (such as prescribing medicines by brand rather than generic name), failure to adhere to standards (such as prescribing guidelines) or clarification of additional instructions (such as before meals) were not recorded by the pharmacist.

inclusion criteria Any medical or surgical patient admitted to the emergency assessment unit could be recruited for the study provided he or she had been seen post-take by a consultant so that the consultant had an opportunity to review the admission notes (usually from the A&E department, where medicines reconciliation is not a priority) and could amend or clarify drug charts if necessary before they were added to the study.

Exclusion criteria No patient was excluded from the study other than those not already seen post-take by a consultant. Ethical approval was not needed because patients and staff were not subjected to any additional intervention other than normal care. Agreement from the emergency assessment unit manager and the clinical director was obtained to undertake the study. It was also notified to the clinical governance department.

The project was carried out in the EAU of the Royal Wolverhampton Hospital NHS Trust, between October 2009 and January 2010. Doctors were not informed of the study, to avoid changes in behaviour.

The study involved 190 patients.The sample size was determined primarily by the practicalities of doing the study over a defined period according to the time available to collect the data.The margin of error defined by a sample size of 200, 6.9 per cent (95 per cent confidence interval) was considered to be reasonable and was used as a guide for the study.

Results

Of the 190 patients included in the study 13 (6.8 per cent) were under surgical care and 177 (93.2 per cent) under medical care. Fifty-two per cent were male, with a mean age of 69.4; 48 per cent were female, with a mean age of 72.8 years.

Rate of interventions

During the four months of the study, the pharmacist intervened for 159 of 190 patients (83.7 per cent), giving rise to 360 interventions (mean, 1.9 per patient). Of these, 16 (4.4 per cent) took place within 24 hours of admission, 290 (80.5 per cent) within 36 hours, 36 (10 per cent) more than 48 hours after admission and 18 (5 per cent) more than 72 hours after admission. The pharmacist made no intervention for 31 patients (16.3 per cent).

Outcome

For all the interventions, the consultant and the pharmacist assessed the potential patient outcome differently. Tables 1 and 2 show the risk rating of the medication issues by both external assessors before and after the pharmacist intervention.

| Table 1: Before intervention Risk rating of medication issue before pharmacist intervention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessor | Red | Yellow | Amber | Green |

| Consultant | 54 (15%) | 124 (34.4%) | 146 (40.5%) | 36 (10%) |

| External pharmacist | 134 (37.2%) | 177 (49.3%) | 46 (12.8%) | 3 (0.8%) |

| Table 2: After intervention Risk rating of medication issue after pharmacist intervention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessor | Red | Amber | Yellow | Green |

| Consultant | 0 (0%) | 4 (1.1%) | 8 (2.2%) | 348 (96.7%) |

| Change from before intervention | -15% | -33% | -38.3% | +86.7% |

| External pharmacist | 7 (1.9%) | 13 (3.6%) | 3 (8%) | 337 (93.6%) |

| Change from before intervention | -35.3% | -45.6% | -4.8% | +92.8% |

Type of intervention

Of the 360 interventions, 32 were not related to a prescribing error; eight related to drug education and the failure to give the patient information about change of medication on admission which, if it continued, could have resulted in patient harm. The remaining 320 interventions related to advice given to a doctor on prescribing and monitoring of drugs. Table 3 provides a breakdown of the type and number of interventions by the clinical pharmacist.

| Table 3: Types of intervention | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type of intervention | Number | Percentage |

| Omission | 82 | 22.8 |

| No need for drug | 15 | 4.2 |

| Abx stopped | 7 | 1.9 |

| Duration | 2 | 0.5 |

| Wrong dose | 43 | 11.9 |

| Side effect | 7 | 1.9 |

| Interaction | 9 | 2.5 |

| Discrepancies | 19 | 5.3 |

| Incomplete | 16 | 4.4 |

| Allergies | 65 | 18 |

| Duplication | 5 | 1.4 |

| Route change | 3 | 0.8 |

| Thromobophrophy | 25 | 6.9 |

| Other | 59 | 16.4 |

| Percentages do not total 100 due to rounding |

As the consultant assessor gave the most conservative risk ratings to the medication-related issues this rating was used in the more detailed analysis of specific types of intervention.

Inaccurate or incorrect taking of a patient’s drug history was the most common reason for intervention by the pharmacist. Of these 82 related to unintentional omission, with 34 considered to have a major potential for medical harm (amber and red alerts).These concerned the omission of antidepressants, benzodiazepines, antidiabetics, antiparkinsonian drugs or muscle relaxants in patients with multiple sclerosis, and cardiac drugs.

A further 43 related to wrong dose, of which, seven were graded as having a major potential for medical harm. One example was the prescribing of phenobarbital at a strength 100 times higher than the patient’s usual dose; 16 related to incomplete prescriptions, of which two were rated as having major potential for medical harm and involved no dose for enoxaparin in patients diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome

Allergies

In 62 instances it was thought there was a major potential for medical harm if allergies were left unresolved.

Thromboprophylaxis

All medication issues related to thromboprophylaxis were considered to have major potential for medical harm if the pharmacist had not intervened.

Discrepancy

There were discrepancies between what was written on the patient record and what was prescribed on the treatment chart. Four discrepancies were considered to have major potential for medical harm.They included failure to initiate nitrates in a patient who came with unstable angina and failure to stop metformin in a patient admitted with acute left ventricular failure.

Side effects

Four side effect issues were considered to have major potential for medical harm and were the cause of admission. Examples included the continuation of two non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medicines in a patient admitted with gastrointestinal bleeding and the continuation of a high dose of atenolol in an elderly patient admitted with collapse and low pulse.

Polypharmacy

Four instances of polypharmacy were considered to have a major potential for medical harm, an example being the continuation of treatment on admission of an elderly patient after a fall who was taking 23 tablets a day, including antihypertensive agents, antidepressants and sleeping tablets.

Unjustified duration of treatment

Long courses of antibiotics were inappropriate in seven instances and were stopped as a result of pharmacist action, but were rated as having little potential for medical harm.

Interactions

All drug interactions were considered to have a major potential for medical harm. An example was the prescribing of clarithromycin to an elderly patient on aminophylline without previously halving the dose or determining levels, or the prescribing of clarithromycin without withholding the co-prescribed statin in view of the increased risk of myopathy.

Patient compliance

One patient compliance was considered to have a major potential for medical harm.

Duplication

Two instances of drug duplication on the treatment chart were rated as having major potential for medical harm, an example being prescribing both paracetamol and co- codamol at their maximum doses.

Change of route

Switching from unnecessary Iv to oral administration happened on three occasions (for paracetamol, tramadol and phenytoin). In all of these, the patient was able to swallow and drug absorption was not compromised by any illness.

Other interventions

Fifty-nine interventions (16.4 per cent) did not fit within any of the categories outlines above. Of these, 20 were judged to have major potential for medical harm, and included the prescribing of vigam infusion incorrectly and the prescribing of certain Iv antibiotics without taking renal function into consideration.

Discussion

The pharmacist made 360 interventions on a total of 190 admissions. In 330 cases (91.7 per cent) the pharmacist’s intervention was accepted. In 30, the recommendation was not accepted or was not productive. In most cases the risk alert was reduced after intervention by the pharmacist; in 91 per cent when assessed by the external pharmacist and in 95 per cent when assessed by the doctor. In no case was the risk of harm increased after pharmacist intervention.

There was agreement on coding in 54.2 per cent of interventions; in general the assessing pharmacist rated the interventions as having greater impact on potential patient outcome than the doctor. There have been some similar studies in the literature that have shown that different healthcare professionals’ assessment of the impact of medication errors differs and often depends on personal experiences.[13],[14]

In this study there was only one member of each discipline and therefore it is difficult to know if the differences were due to individual assessors or to their clinical profession. Perhaps this could be investigated further, with two members of each discipline assessing each intervention instead of one. The agreement on coding could therefore be explored both intra- and inter-professionally.

Some 83.7 per cent of patients in the study were found to have at least one drug-related issue that needed pharmacist input. Although this figure may look higher than the figures quoted by other workers, it is important to bear in mind that in this study the denominator is hospital admissions while most of the studies done in the UK, such as the one carried out by Dean et al are based on the total number of medicine orders written and, therefore, their figures will appear smaller.[8]

This study also differs from many other published studies in that it attempted to measure the potential medical impact of the pharmacist’s interventions with regard to drug- and pharmaceutical care-related issues and not solely those generated by prescribing errors.

In this study the pharmacist interventions relating to prescribing errors accounted for 91.1 per cent of the total, whereas in another recently published study only 52 per cent of pharmacist interventions related to a prescribing error.[15]

This difference could be because the latter study was conducted in a 28-bed general surgery ward, whereas this study was conducted in an emergency assessment unit.

Thus the patient population in this study was different, being primarily medical patients (177 medical versus 13 surgical) who usually present with multiple co-morbidities and would probably be on more regular and varied medication than the surgical patients. Furthermore, the turnover of patients in the EAU is faster than in a surgical ward thus increasing the risk of prescribing errors.

Another published study carried out in a similar environment to ours identified 740 prescribing errors in a total of 235 acutely ill medical patients with the mean number of errors being 3.06 per patient,13 which is higher than our intervention rate of 1.9 per patient. However, the proportion of pharmacist interventions relating to prescribing errors in study (91.1 per cent) is similar to that in a published study in a psychiatric hospital (93.4 per cent).[16]

Although the setting where the study was conducted was different, the definitions of prescribing error used by the authors were the same as ours, meaning that the potential errors would have been measured in the same way.

The results from this study showed that most of the care issues identified related to prescribing errors originating in the process of writing the prescription rather than in the prescribing decision: 228 versus 100 (69.5 per cent versus 30.5 per cent).These results are similar to those reported in other studies.[7],[8],[16]

In this study, the highest error rate related to poor medication history-taking and prescribing.The medication history taken by the doctor during the initial clerking was compared with that taken by the pharmacist on review.

Some 48.4 per cent of patients admitted to the EAU had at least one error in their medication histories giving an average of 1.5 errors per patient. These figures are lower than in other studies, such as the one carried out by McFadzean et al,[9]

where 65 per cent of the patients admitted to the admission unit had errors in their drug history.

However, in the McFadzean study the definition of a prescribing error was different from ours. It included actions such as the use of lower case letters when writing the prescription, abbreviations of micrograms or units and omission of the prescriber’s signature as prescribing errors, whereas we did not record these as errors.

Inaccuracies were more often seen with certain medicines: inhalers were most likely to be omitted or incorrectly prescribed (16.3 per cent of the 141 prescribing errors under this category), followed by analgesics (9.9 per cent), calcium supplements (9.2 per cent), diuretics and levothyroxine.These medicines have also been identified in other UK studies as being associated with more errors.[7],[17]

In this study some therapeutic or pharmaceutical groups of medicines were commonly involved in the pharmacist’s intervention for different reasons, such as prescribing the wrong dose, wrong strength or wrong frequency, or not prescribing it at all.

These groups included common medicines such as inhalers, topical preparations, analgesics and calcium supplements, as well as medicines such as low molecular weight heparin for thromboprophylaxis, which was often not prescribed when it should have been.

Recommendations

The Medical Schools Council and the British Pharmacological Society — as a result of the evidence accumulated in different studies and concern about the poor quality of prescribing in the UK — have announced that new doctors will face a prescribing assessment from 2014 where they will have to demonstrate that are competent to prescribe.[18],[19]

The data on pharmacist intervention rates in study confirms that prescribing errors are a potential major cause of harm to patients admitted to the emergency assessment unit. However, actual harm to the patient is prevented in most cases by the action of the pharmacist. These data concur with the results of the General Medical Council’s own study on junior doctor prescribing.[11]

We found that medication history inaccuracies were the most common type of error, occurring more than twice as frequently as the next most frequent error type.This finding concurs with the analysis of all the Royal Wolverhampton Hospital NHS Trust pharmacists’ interventions where medicines reconciliation accounted for 910 out of a total of 2,010 pharmacist interventions in the quarter.[20]

The study agrees with others in that pharmacists have been shown to be better than doctors in taking accurate drug histories and, although it could be argued that patients may give more accurate information once they are questioned for the second time after the initial assessment by the doctor, pharmacists may still be the ideal people to undertake this task as they have a broad pharmacological knowledge, and this can help when discussing drug treatment and over-the-counter medicines with patients.

This study showed that in many cases (37 per cent) obtaining an accurate drug history was due to using at least two sources of information rather than one. Unfortunately, doctors in the EAU work under pressure and may not have the time to look for a second source of information. The results of this study would support the case for an independent prescriber pharmacist as an improvement in patient safety has been shown and such an appointment would free doctors’ time for carrying out other tasks.[9]

As well as errors in medication histories this study shows that a limited number of errors involving certain drugs occur repeatedly, such as the interaction between statins and macrolides. Targeted educational measures, such as monthly prescribers newsletters, have been implemented in some hospitals with success,[21]

and in our hospital feedback to groups of prescribers on common errors is being introduced.

After this study was completed, and in line with the medicines reconciliation guidelines (from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and the NPSA),[5]

the Royal Wolverhampton Hospital NHS Trust developed a new treatment chart with an additional box for pharmacy documentation such as medication history so that accurate information is transferred from one ward to another. An additional box for the recording of thromboprophylaxis only has also been added. In addition to this, the pharmacist writes the medication history, together with any changes, omissions or discrepancies.

The trust went live with electronic prescribing early in 2012. A recent study showed that electronic prescribing improved the quality of prescribing by reducing both prescribing errors and the need for pharmacists’ clinical interventions. However, some new types of error were introduced, such as selection of the incorrect product dose or frequency from a menu, and inappropriate use or selection of default doses.[15]

It would be interesting to repeat this study once electronic prescribing is fully established in the trust and to compare the number of interventions made before and after, but this is outside the scope of this study.

Limitations

Our study has a number of limitations: first, it was conducted only in the EAU at one teaching hospital. However, studies carried out in other hospitals in the same kind of setting have produced similar results.

Secondly, the prescribing error rate may be underestimated, since it is impossible to be sure that the pharmacist identified all of them. Conversely, the pharmacist in the EAU (the author) was aware of the study and may have acted differently from normal (the Hawthorn effect). However, the time spent by the pharmacist on the unit was no longer than usual and interventions were accepted in 91.7 per cent of the cases, indicating they were not unreasonable.

Finally, the consultant assessor was aware of the study and was actively involved in the unit, and this could have introduced bias.

Conclusions

The pharmacist in the EAU routinely made interventions on prescriptions over the course of the study and most of them related to preventable prescribing errors. A high proportion of interventions related to errors in medication histories and further work to improve medication history-taking on admission is needed.

The intervention of the clinical pharmacist significantly improved the predicted patient outcome by reducing the risk of harm in most cases.

There have been few studies that have attempted to assess the clinical impact of pharmacist interventions, so further work is needed in this area to build on the findings here.

Within the Royal Wolverhampton Hospital NHS Trust, a routine monitoring and feedback system to groups of doctors has been introduced as a learning tool, by highlighting common errors. The impact of this approach warrants further investigation.

About the authors

Maria Alonso-Jura, MSc, MRPharmS, is homecare pharmacist at Milton Keynes Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (email maria.alonso-jura@mkhospital.nhs.uk)

References

[1] Pharmacy. The report of a committee of enquiry to the Nuffield Foundation. Nuffield Foundation. 1986.

[2] American College of Clinical Pharmacy. A vision of pharmacy’s future roles, responsibilities and manpower needs in the United States. Board of Pharmaceutical Specialties. Pharmacotherapy 2000;8:991–1020.

[3] White Paper. Pharmacy in England: building on strengths, delivering the future, proposals for legislative change. Department of Health, London: Stationery Office, 2008.

[4] Campbell F, Karnon J, Czosky-Murray C et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of interventions aimed at preventing medication error (medicines reconciliation) at hospital admission. Report commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. School of Health and Related Research, University of Sheffield, 2011.

[5] National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence/National Patient Safety Agency. Technical patient safety solutions for medicines reconciliation on admission of adult to hospital. London: NICE/NPSA, 2007.

[6] Dean BD, Vincent C, Schachter M et al. The incidence of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients. Drug Safety 2005;28:891–900.

[7] Dean BD, Vincent C, Schachter M et al. Causes of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a prospective study, Lancet 2002;359:1373–8.

[8] Dean BD, Vincent C, Schachter M et al. Prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: their incidence and clinical significance. Quality and Safety in Health Care 2002;4:340–4.

[9] McFadzean E, Isles C, Moffat J. Is there a role for a prescribing pharmacist in preventing prescribing errors in a medical admission unit? Pharmaceutical Journal 2003;270:896–9.

[10] Unsustainable rise in emergency admissions is avoidable and no longer affordable. London: Nuffield Trust, 2010.

[11] Dornan T, Ashcroft D, Heathfield H. An in-depth investigation into causes of prescribing errors by foundation trainees in relation to their medical education. EQUIP study, Hope Hospital, University of Manchester Medical School Teaching Hospital, 2009.

[12] Bond CA, Raehl CL, Franke T. Clinical pharmacy services and hospital mortality rates. Pharmacotherapy 1999;19:556–64.

[13] Dale A, Copeland R, Barton R. Prescribing errors on medical wards and the impact of clinical pharmacists. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2003;1:19–24.

[14] Dean BS, Barber ND. A validated, reliable method of scoring the severity of medication errors,American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 1999;56:57–62.

[15] Donyai P, O’Grady K, Jacklin A et al. The effects of electronic prescribing on the quality of prescribing. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2008,65:230–7.

[16] Stubbs J, Haw C, Cahill C. Auditing prescribing errors in a psychiatric hospital. Are pharmacist interventions effective? Hospital Pharmacist 2004;11:203–6.

[17] Honnet R. Clinical pharmacy in acute medical admissions. Pharmacy Management 2006;22:17–21.

[18] Prescribing test to be introduced for new doctors. Pharmaceutical Journal 2009;283:672.

[19] Prescribing skills assessment. Available at: bma.org.uk/developing-your-career/studying-medicine/prescribing-skills-assessment (accessed 15 August 2013).

[20] Last quarterly medicines management report Q1 2011/12. The Royal Wolverhampton Hospital NHS Trust.

[21] Hawkey CJ, Hodgson S, Norman A. Effect of reactive pharmacy intervention on quality of hospital prescribing. BMJ 1990;300:986–9.