Abstract

Aim

To describe the first year of operation of a novel pharmacy service, developed from a pharmaceutical needs assessment.

Design

An analysis of data routinely collected from patient contacts.

Subjects and setting

All patients who accessed the pharmacy service at the Healthy Hoose, a “first-stop” drop-in health centre in Aberdeen, between 8 June 2002 and 30 May 2003.

Outcome measures

Reason for consulting the pharmacist, service required by the patient, pharmaceutical care issues identified and addressed during the consultation, and referrals made by the pharmacist.

Results

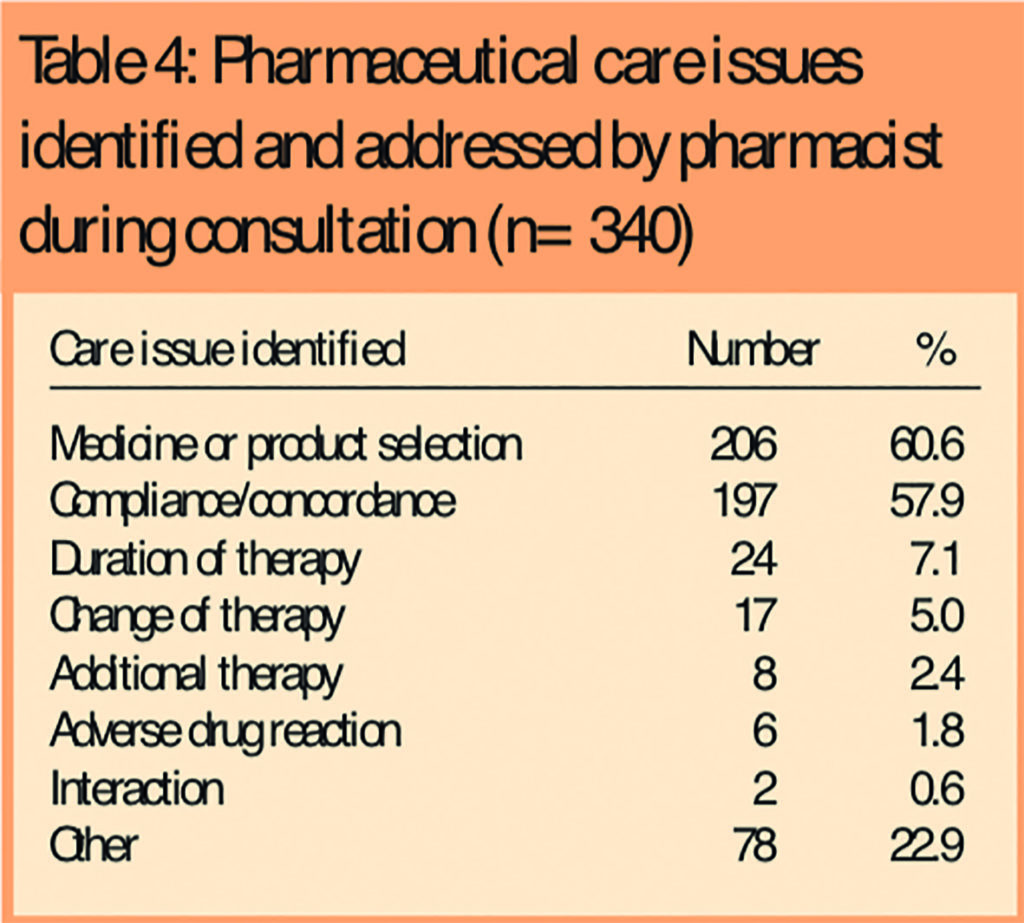

There were 340 consultations with the pharmacist. The most common reasons for consultations were head lice, prescription collection and smoking cessation. Most consultations resulted in the provision of advice or the supply of a medicine or both and could be managed by the pharmacist without referral to other health professionals. The selection of the most appropriate medicine was a care issue in six out of 10 consultations, closely followed by compliance and concordance.

Conclusions

The provision of needs-based pharmacy services can increase access to health services. The supply of a limited range of treatments for minor ailments free of charge to patients who do not normally pay prescription charges can reduce the demand for GP consultations that result from the limited ability of these patients to afford over-the-counter medicines. Many of the services provided by the pharmacist have wider public health benefits.

Access to pharmaceutical services and addressing health inequalities are key elements of the strategies outlined in “The right medicine”1 and “Pharmacy for health”.2 Deprived areas often have limited access to health services, including doctors’ surgeries and pharmacies. Even when health care services are available they may not necessarily be those most needed or wanted by the community. Potential users of these services and barriers to their use may not be immediately recognisable. Therefore needs assessments are necessary to inform, prioritise and guide the development of health services.

Middlefield is a deprived area of Aberdeen with a population of around 2,300.3 In terms of health and overall deprivation it is among the worst 10 per cent of communities in Scotland.4 In Middlefield, a pharmaceutical needs assessment was used to guide the development and implementation of a novel pharmacy service located in a “first-stop” drop-in health centre known as the Healthy Hoose. The Healthy Hoose was established in August 1999 to provide nursing and health promotion services to the local community. At the time of the pharmaceutical needs assessment, it was staffed by a nurse prescriber, a nurse practitioner, a health promotion worker and a secretary/receptionist.5 There was not a GP either at the Healthy Hoose or based in Middlefield.

Recommendations made after the pharmaceutical needs assessment was carried out appear in Panel 1.5

Panel 1: Recommendations made after the pharmaceutical needs assessment was carried out

- A part-time, limited community pharmacy service should be introduced in the first instance, with an option to expand where need demands. If possible, opening hours should be different on different days of the week.

- The services that should be provided from the outset are advice on minor illnesses and advice on and sales of over-the-counter medicines.

- Only the most basic medicines should be stored on the premises initially.

- Appropriate security arrangements must be made for the storage of medicines.

- A prescription collection service should be introduced where prescriptions are dispensed in an existing community pharmacy and transported to the Healthy Hoose for collection.

- Drug misuse services should not be located in the Healthy Hoose but, where future work proves the need, consideration could be given to locating them in alternative premises.

In May 2002 a pharmacy service based on these recommendations started up within the Healthy Hoose. In September 2002 the premises were registered as a pharmacy.

The introduction of “direct supply” arrangements in November 2002 enabled the pharmacist to supply patients normally exempt from prescription charges with treatments listed in the Healthy Hoose formulary (see Panel 2) at no charge. Medicines supplied under these arrangements are obtained on “Stock order for drugs and appliances NHS Scotland — GP10(a)” from the community pharmacy that is contracted to provide the pharmacist’s services.

Panel 2: Healthy Hoose formulary with pack sizes held

Gastrointestinal

- Co-magaldrox 500ml

- Gaviscon SF suspension 200ml (or 100ml)

- Gaviscon tablets 24

- Ispaghula husk 3.5g 10

- Senna tablets 30

- Loperamide 2mg capsules 10

- Dioralyteoral powder 6

Respiratory/allergy

- Loratadine 10mg tablets 7

- Chlorpheniramine 4mg tablets 30

- Chlorpheniramine syrup 2mg/5ml 150ml

- Sodium cromoglicate 2% eye drops 5ml

- Beclometasone 50μg nasal spray 100 dose

- Simple linctus 200ml

- Paediatric simple linctus 100ml

- Pseudoephedrine 60mg tablets 12

- Pseudoephedrine 30mg/5ml elixir 100ml

- Xylometazoline 0.1% nasal drops 10ml

Analgesia

- Paracetamol tablets 500mg 32

- Paracetamol effervescent 500mg 24

- Paracetamol 120mg dispersible 16

- Paracetamol 120mg/5ml 100ml

- Paracetamol 250mg/5ml suspension 100ml

- Ibuprofen tablets 200mg 24

- Ibuprofen tablets 400mg 24

- Ibuprofen 100mg/5ml suspension 100ml

Infection/infestation

- Clotrimazole Combi 1

- Clotrimazole vaginal tablets 500mg 1

- Clotrimazole cream 1% 20g

- Aciclovircream 5% 2g

- Mebendazole 100mg tablet 1

- Mebendazole 100mg tablet 4

- Pripsenoral powders 2

- Malathion 0.5% lotion 50ml

- Malathion 0.5% lotion 200ml

- Malathion 0.5% liquid 50ml

- Malathion 0.5% liquid 200ml

- Phenothrin 0.2% lotion 50ml

- Phenothrin 0.2% lotion 200ml

- Phenothrin 0.5% liquid 50ml

- Phenothrin 0.5% liquid 200ml

Skin

- Benzoyl Peroxide Aquagel 2.5% 40g

- Benzoyl Peroxide Aquagel 5% 40g

- Benzoyl Peroxide Aquagel 10% 40g

- Aqueous cream 100g (or 500g)

- Emulsifying ointment 100g (or 500g)

- Eurax cream 30g

- Hydrocortisone cream 1.0%1 5g

Nicotine replacement therapy

- Nicotine patch 21mg/24hour 7

- Nicotine patch 14mg/24 hour 7

- Nicotine patch 7mg/24 hour 7

- Nicotine lozenges 4mg 72

- Nicotine lozenges 2mg 72

- Nicotine gum 4mg 96

- Nicotine gum 2mg 96

The aim of the work reported here was to use routinely collected data to describe the patient consultations during the first year of operation. In years 2 and 3, there were several changes in record systems, and movement to a single data collection tool for all consultations and health professionals working in the Healthy Hoose. Records from these consultations were not sufficiently detailed or categorically compatible for in-depth analysis.

Methods

Advice on minor illness, advice on and sales of OTC medicines, and a prescription collection service were the services initially provided at the Healthy Hoose pharmacy. As the services developed, the pharmacist also performed medication reviews for patients over 75 years of age registered at the local GP surgery, produced medication charts for a local intermediate care facility that mainly catered for patients recently released from hospital, and delivered an educational session for children and their parents at a local primary school. The last of these was excluded from this analysis.

Data were recorded after each consultation with the pharmacist from 8 June 2002 until 30 May 2003. A standard data collection form was completed by the pharmacist delivering the service. The data included the presenting complaint, the pharmaceutical advice provided, care issues identified by the pharmacist and whether the patient was referred to another health care provider. Demographic data were collected for patients who consulted the pharmacist for anything other than the purchase of a simple OTC medicine. Demographics were analysed on a patient basis rather than a consultation basis.

The last day of data collection, ie, 30 May 2003, was used to calculate the age of patients, regardless of consultation date. Data were recorded in a Microsoft Access database and the analysis was undertaken using tools available within that software, eg, count (frequency) and average.

Results

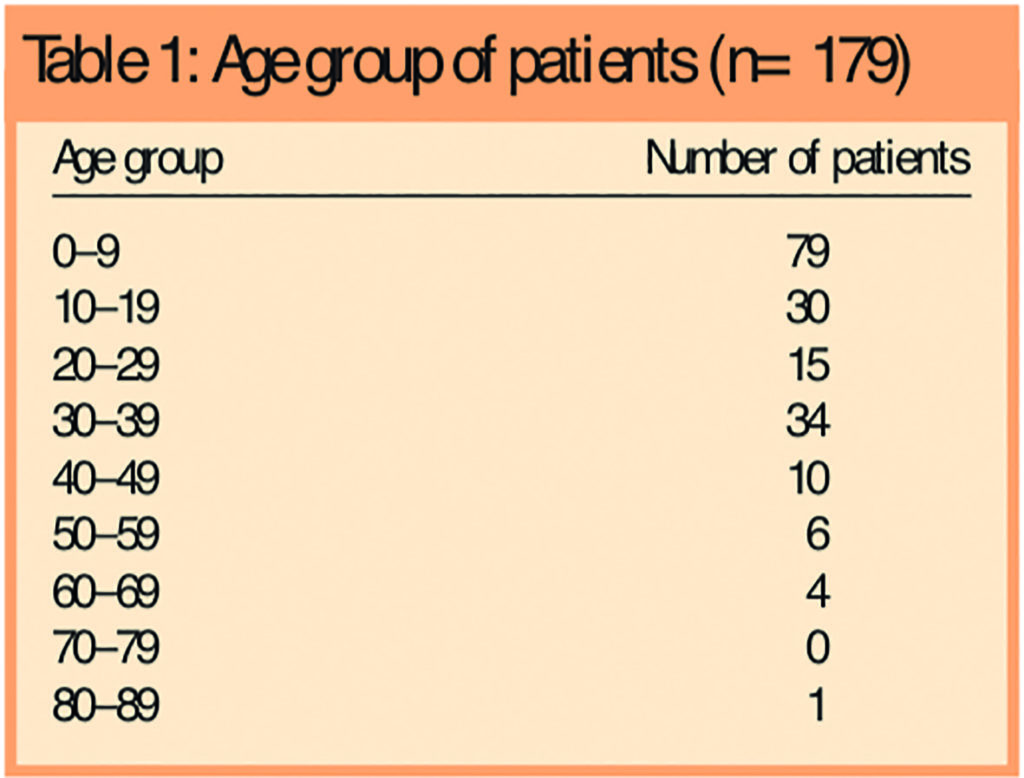

In the first year of the service there were 340 consultations with the pharmacist, including 26 requests to purchase OTC medicines where no patient demographic data were collected. An analysis of the remaining 314 consultations showed that there were 179 patients involved in these consultations. Most patients (118) consulted the pharmacist only once, however, one patient attended 12 times. Four out of five (144) patients were female. Patients ranged in age from three months to 81 years. Small children and those in their fourth decade comprised the biggest user groups (Table 1).

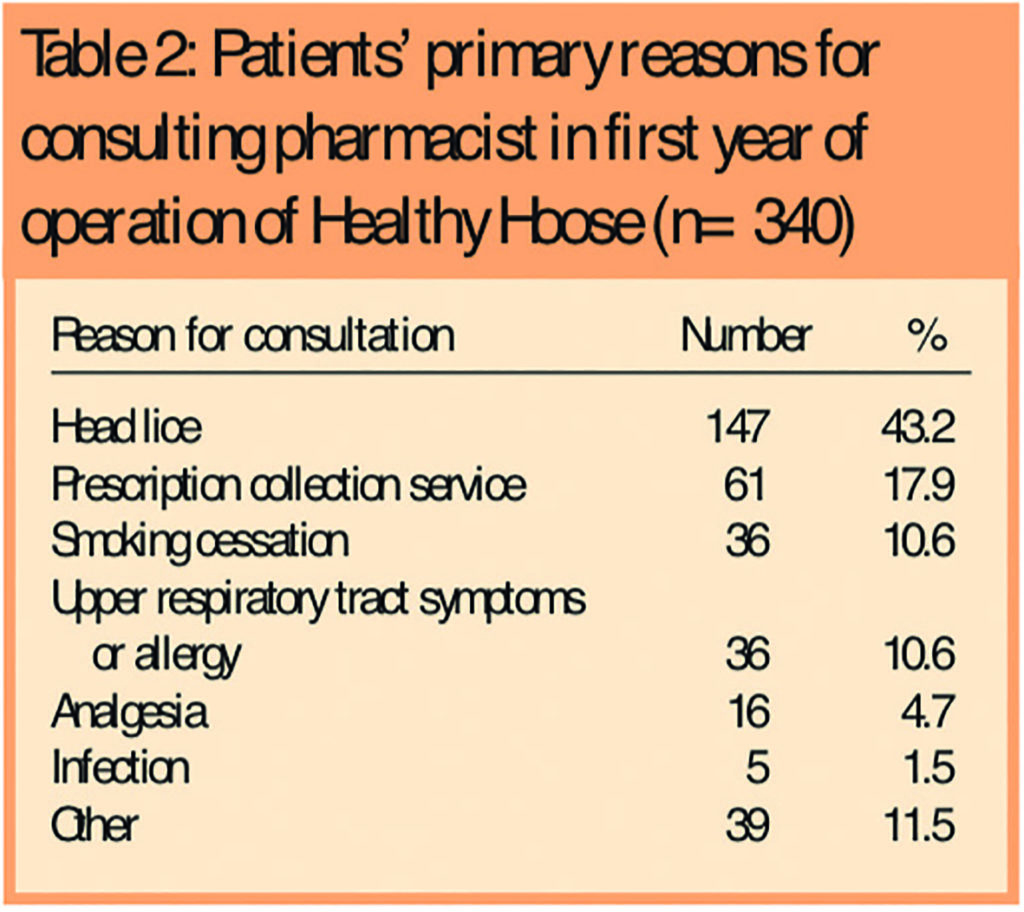

Headlice was the most common presenting complaint followed by the desire to give up smoking (Table 2).

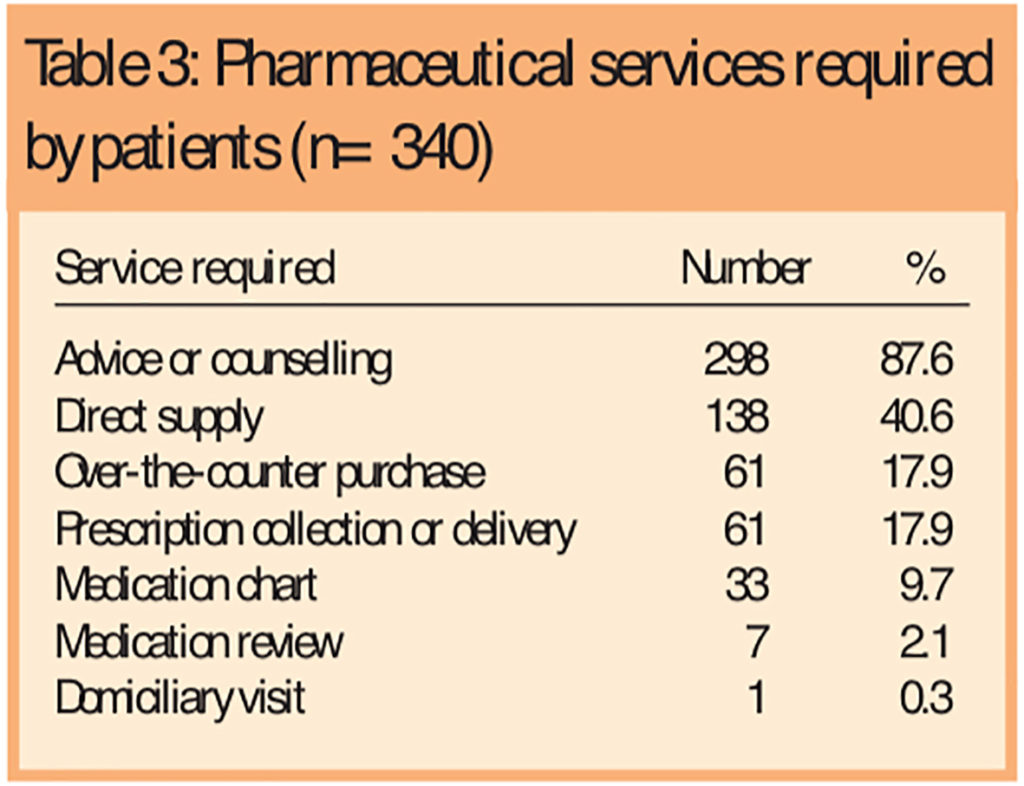

Consultations were usually for advice, supply (either direct to the patient or through OTC sales) or a combination of these (Table 3) with the pharmacist frequently providing advice on the most appropriate treatment (Table 4) and its use.

Lifestyle counselling was provided, either in response to a direct request or opportunistically, to half the patients.

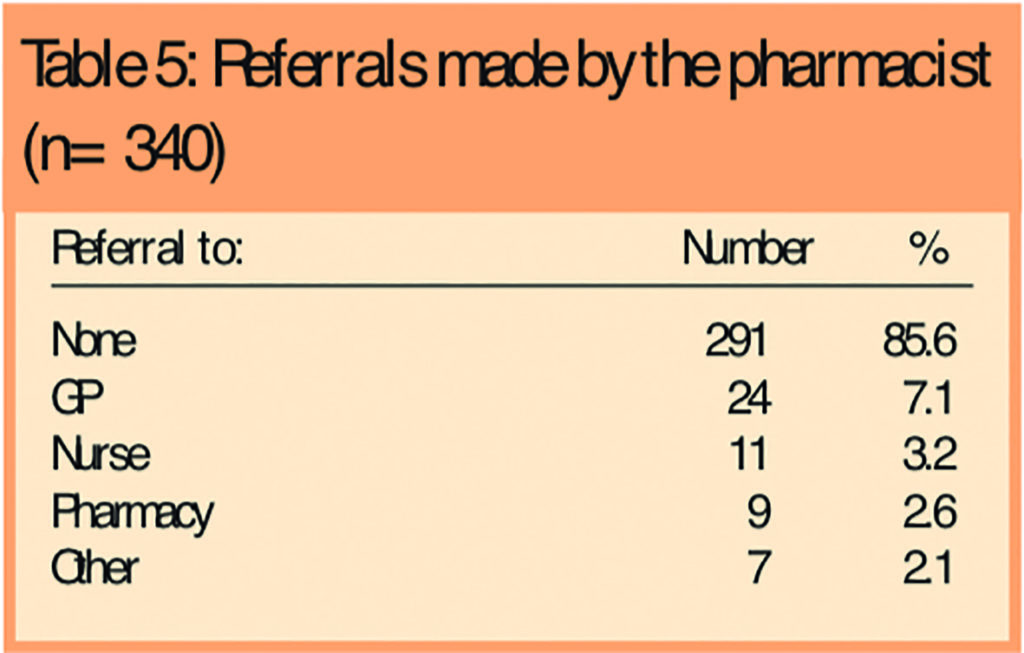

The pharmacist managed most of the consultations (85.6 per cent) without the need for referral to other health practitioners or agencies (Table 5).

Owing to the limited stock of medicines kept at the Healthy Hoose a referral to a community pharmacy to obtain an OTC medicine was sometimes required. No referrals were made to hospital.

Discussion

Using routinely collected data we have quantified pharmacy contacts at a “drop-in” pharmacy service. Most clients were either small children or were in their 30s and many returned for further advice over the period. Most were managed by the pharmacist without the need to refer on to other professionals.

A weakness of this retrospective study is the limited insight into the effectiveness of the intervention, or comparisons with other providers. However while, ideally, service innovations should be evaluated using the best methods, eg, a randomised controlled trial, in practice it would not be cost-effective to do this. Simpler approaches, as described in this paper, show the potential from analysing routinely collected data to monitor a service and inform its future development.

The pharmacist’s room in the Healthy Hoose is now a registered pharmacy but it is not a dispensing pharmacy. This is because the pharmacy service was designed and established to meet the needs of the population that were identified in the pharmacy needs assessment (see Panel 15).

The initial pharmacy service was almost identical to that outlined in the recommendations of the needs assessment. This included the prescription collection service with prescriptions dispensed in an existing community pharmacy and transported to the Healthy Hoose for collection — an aspect of the service that aimed to address concerns about security and the storage of drugs on the premises. The only variation to the recommendations was a minor one: the pharmacy opened four mornings per week (Monday to Thursday). This was done to avoid the confusion associated with varying opening times.

One of the initial recommendations was that the pharmacy should provide advice on minor illness and sales of over-the-counter medicines. Most community pharmacists would be familiar with the reasons why patients at the Healthy Hoose consulted the pharmacist (Table 2); however the way the pharmacist dealt with these is somewhat more unusual.

The physical structure of the “pharmacy” is a consulting room. Here the pharmacist focuses on professional services, eg, providing advice and promoting health. In addition to this, the pharmacist can supply a range of medicines direct to the patient at no charge, removing the need for patients to visit their GP in order to get a prescription for an OTC medicine because they cannot afford to buy it. Given the deprived nature of the Middlefield area it is likely that this service saved over 100 GP visits.

Before the Healthy Hoose opened, patients had to travel outside the Middlefield area to obtain medical or pharmacy services. This resulted in both direct and indirect patient costs, for example, time and inconvenience, especially for parents trying to negotiate bus travel with children and pushchairs. The Healthy Hoose is within walking distance for most of the Middlefield population and there is no need to make an appointment. Here, in line with current policy, we have secured substantial improvements in access.

There is a current policy driver to empower patients and encourage them to take control of their own health. In the Healthy Hoose time is taken to explain OTC and prescription medicines so that patients have a better understanding of their use. Reactive and opportunistic educational advice is provided so that patients learn how to self-manage the minor illnesses and symptoms they present with, and understand important health issues and small changes to their lifestyle, eg, in weight, exercise and smoking status, that could have long-term benefits.

Service development

Initially there were concerns that there would be duplication of the services provided by nurses and other staff at the Healthy Hoose with those provided by the pharmacist.5 Although this was not addressed in any formal evaluation, based on our observations, duplication is not a problem. The pharmacist has also noted that many patients were unaware of the services she could provide, especially those related to self-care and health promotion, eg, general advice on disease prevention, diet, minor ailments, and chronic diseases. We believe that an increased awareness among both staff and patients of what the pharmacist can do has meant that, as time passes, the specialist knowledge and skills of the pharmacist are better used, especially when it comes to treatment selection and advice. The nurses, who have extended prescribing rights, now consult the pharmacist for prescribing advice.

In general, the service aims for the patient’s needs to be addressed by the most appropriate health practitioner; referrals from the nurses to the pharmacist and vice-versa are not uncommon.

The data presented in detail were from the first year of the service and reflect the time required to establish the service and build patient relationships. Although initial usage was low, as more residents became aware of the service and the pharmacist’s skills, demand increased. Current demand is more than double that experienced in the first year. There were 552 consultations with the pharmacist in the second year of operation and 191 in the first quarter of the third year (personal communication, Healthy Hoose pharmacist). From January 2004 the pharmacy opened five mornings a week in order to provide a needle exchange service on Friday mornings.

Future plans

The service is constantly evolving in response to identified population needs and changes in pharmacy practice. The updating of the computer software at the Healthy Hoose will present an opportunity to capture more data including details of the information and education provided by the pharmacist, a necessary step if we are to demonstrate the full potential value of these services.

The pharmacist registered as a supplementary prescriber in June, and we hope to extend the service to include the management of chronic illness. There are good links with the nearest GP surgeries and the pharmacist has electronic access to some patients’ medication histories. Electronic access to patient records should increasingly be possible as linkage of community pharmacies to the NHSnet is rolled out. The chronic medication service should be of great benefit to residents with limited mobility or restricted transport options or both.

The knowledge gained and lessons learnt from setting up and operating the Healthy Hoose pharmacy are being used to develop other services that meet the needs of groups of people in Grampian who have poor health outcomes. The benefits to public health of this service are substantial. Future services may not necessarily use the same model of service delivery but the principle of the delivery of community pharmacy services from a non-traditional base will be repeated. A central focus of these services will be a pharmacist addressing individual patients’ problems and providing services that have wider public health benefits, eg, smoking cessation and drug misuse services, in an easily accessible manner, based on population needs.

This paper was accepted for publication on 26 July 2005.

About the authors

Michelle King, PhD, MRPharmS, is a lecturer in the department of general practice and primary care at the University of Aberdeen and public health pharmacist at NHS Grampian. Kathleen McFarlane, MPharm, MRPharmS, is the pharmacist at Middlefield Clinic, Aberdeen. Linda Juroszek, MPharm, MRPharmS, is a lead pharmacist at Aberdeen Community Health Partnership, and Christine Bond, PhD, FRPharmS, is professor of primary care in the department of general practice and primary care at the University of Aberdeen and consultant in pharmaceutical public health at NHS Grampian.

Correspondence to: Dr King at Department of General Practice and Primary Care, University of Aberdeen, Foresterhill Health Centre, Westburn Road, Aberdeen AB25 2AY (e-mail michelle.king@abdn.ac.uk)

References

- Scottish Executive Health Department. The right medicine: a strategy for pharmaceutical care in Scotland. Edinburgh: SEHD; 2002.

- Braddick L, Bryson S, Crawford F, Parkinson J, Pfleger S. Pharmacy for health: the way forward for pharmaceutical public health in Scotland. Glasgow: Public Health Institute of Scotland; 2002.

- Aberdeen City Council 2001 census. Neighbourhood statistics. Aberdeen: Aberdeen City Council; 2004.

- Office of Chief Executive. Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation 2004: analysis of Aberdeen data. Aberdeen: Aberdeen City Council; 2004.

- Porteous T, Bond C. Novel provision of pharmacy services to a deprived area: a pharmaceutical needs assessment. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2003;11:47-54.