THOMAS DEERINCK, NCMIR / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Mycoplasma genitalium infection can be associated with clinical disease in men and women. However, the challenge of correctly identifying it, alongside widespread overuse of single-dose azithromycin 1g for non-specific genital infections, has resulted in subtherapeutic selection pressures driving macrolide resistance.

It is vital that all healthcare professionals who may be involved in the detection and treatment of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) understand the features of M. genitalium infection and how to manage it. This article discusses the 2018 guidelines from the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) on diagnosing and treating M. genitalium infection[1]

.

What is M. genitalium?

This pathogen is a bacterium of the Mollicutes class, which is able to invade, adhere to and colonise the urethra and genital tract through sexual contact[2]

. At 580 kilobases, it has the smallest genome of any known bacterium[1]

.

The UK prevalence of M. genitalium infection is around 1.2% for men and 1.3% for women, with peak prevalence at ages 25–34 years and 16–19 years, respectively[3]

. Black men are also disproportionately affected[3]

. For both men and women, unprotected sex and higher numbers of new and total partners are strongly associated with an increased risk of M. genitalium infection[3]

.

While there is a predominance of M. genitalium infection in the lower genital tract, rectal carriage is also common without causing disease[4]

. Oral–genital transmission is possible, but studies so far have shown very low rates of pharyngeal M. genitalium

[5]

.

Although a seemingly uncommon pathogen in the general population, M. genitalium is a cause of non-gonococcal urethritis (NGU) — sometimes referred to as non-specific urethritis — in men, with a prevalence of 10–35%[6]

.

Signs and symptoms

The majority of M. genitalium infections are asymptomatic[3]

. However, when patients are symptomatic, men present with NGU (i.e. dysuria and/or urethral discharge)[7]

, while symptomatic women present with features of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID; i.e. pelvic pain and/or dyspareunia [pain during sexual intercourse] and/or post-coital bleeding)[8]

.

Complications

Athough they are rare in men, complications such as reactive arthritis and epididymo-orchitis (pain and swelling in the scrotum) owing to ascending infection have been reported[7]

. For women, stronger evidence implicates endometritis and salpingitis (inflammation of the fallopian tubes) as complications[9]

. M. genitalium infection is also implicated as a potential cause of tubal infertility and preterm birth[8]

.

Diagnosis

Historically, a lack of availability of M. genitalium testing, as well as poor test sensitivity and inadequate validation of assays, has not permitted adequate diagnosis.

M. genitalium is not visible under light microscopy. It has a slow replicative cycle with extremely fastidious growth requirements and, therefore, culture takes weeks to months. This is impractical, which means that molecular assays offer the most effective method for timely diagnosis. However, they lack both sensitivity and adequate laboratory validation and, therefore, have not been extensively used.

Newer nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) enable the detection of M. genitalium DNA or RNA from clinical samples. NAATs are more sensitive and are increasingly being implemented in UK laboratories, although they are subject to local validation[9]

. The recommended patient samples for use in testing are first-void urine in men and a vaginal swab in women that can be either obtained by patients themselves or by a healthcare professional.

Testing for M. genitalium is strongly recommended for[1]

:

- Men presenting with features of NGU;

- Women with signs and symptoms suggestive of PID;

- Anyone whose current sexual partner has confirmed or suspected M. genitalium infection.

For the majority of patients, M. genitalium does not cause disease and there is currently insufficient evidence to recommend screening for M. genitalium at the population level[10]

.

Detecting antimicrobial resistance

Global rates of resistance to macrolides are alarmingly high (see Figure 1)[7],[11],[12], [13],[14],[15],[16],[17],[18],[19],[20],[21],[22],[23],[24],[25],[26]

. Currently, the prevalence of macrolide resistance in the UK is thought to be around 40% and ranges from 30% to 100% globally[27],[28]

.

Figure 1: Worldwide prevalence of macrolide and quinolone-resistant Mycoplasma genitalium

MR: Macrolide resistance; QR: Quinolone resistance

Int J Circumpolar Health

11

, Sex Transm Infect

12

, PLoS One

13, Int J STD AIDS

14, Clin Infect Dis

15, BMJ Open

16, J Antimicrob Chemother

17, Sex Transm Infect

18, PLoS One

19, J Clin Microbiol

20, Emerg Infect Dis

21, Sex Transm Dis

22, Clin Infect Dis

23, Emerg Infect Dis

24, J Clin Microbiol

25, J Clin Microbiol

26, Clin Infect Dis

27

The prevalence of quinolone resistance in the UK is currently unknown; however, one UK study investigating antibiotic-resistant M. genitalium in NGU identified one patient infected with a strain demonstrating genotypic resistance to fluoroquinolones[27]

.

M. genitalium develops resistance to macrolides via mutations emerging in region V of the 23S rRNA gene, particularly at nucleotide positions 2058 and 2059, which inhibit the binding of macrolides and thus are associated with treatment failure[29],[30]

. Alongside identification of the organism, the clinical sample should be tested for the presence of these macrolide resistance-associated mutations where possible. Commercial molecular macrolide susceptibility genotyping assays can determine the macrolide-sensitivity of the M. genitalium strain[9]

, which allows for resistance-guided treatment to be offered. However, most UK centres do not have access to resistance assays.

Treatment

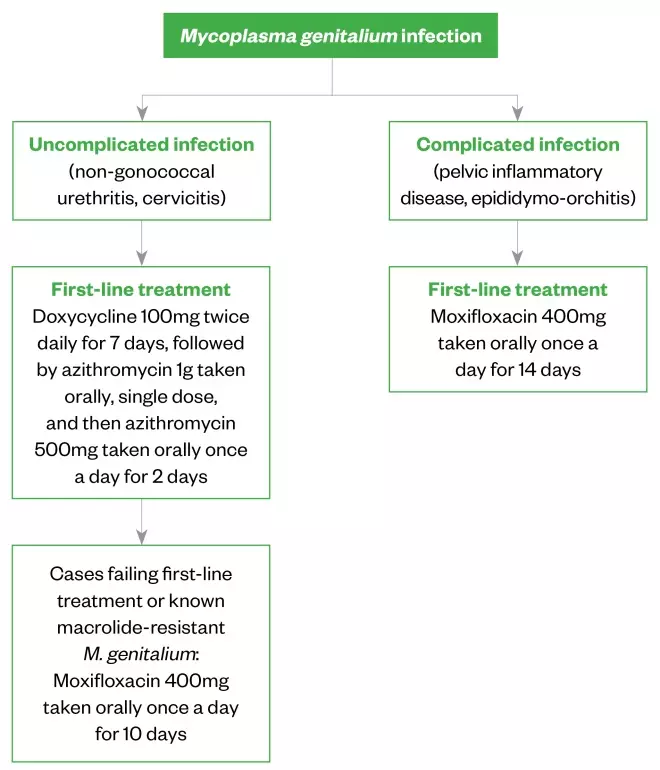

If baseline resistance data are unavailable, the choice of treatment should be determined by the severity and presentation of infection (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Recommended treatment regimens for different presentations of Mycoplasma genitalium infections

British Association for Sexual Health and HIV

1

Azithromycin

This is the first-line treatment; however, resistance is increasing, likely owing to the inappropriate use and overuse of single-dose azithromycin 1g to treat chlamydia and non-specific genital infections, such as NGU. Azithromycin 1g is insufficient to clear M. genitalium given its slow replication.

Although high doses of azithromycin are poorly tolerated, if an organism is known to be macrolide-sensitive, it is likely that a higher dose in divided doses should clear the infection and be less likely to be selected for macrolide-resistance. However, substantial evidence for this is lacking[7]

.

Azithromycin therapy should not be repeated following treatment failure because it is likely that the organism will have developed resistance to treatment. Furthermore, single-dose azithromycin 1g should no longer be used for empirical treatment of STIs.

Doxycycline

This has a poor clearance rate of M. genitalium when given as monotherapy (around 30–40%)[7]

. However, doxycycline reduces bacterial load and may improve treatment success when followed by azithromycin[7],[23]

. Doxycycline has now been adopted as first-line management for urethritis (see Figure 2). Most individuals will be given doxycycline intially, as this is standard for uncomplicated genital infection. A repeat course of doxycycline is therefore unnecessary in cases confirmed to have M. genitalium; azithromycin should be given immediately after (but within two weeks of) the final doxycycline dose.

Moxifloxacin

This should be used first-line in cases of confirmed M. genitalium with complicated infection, such as PID and epididymitis, as these require prompt and effective treatment. Typically, a 10-day course is preferred, as treatment failure rate following 7-day regimens is marginally higher[31]

; a 14-day course may be recommended with complicated infection.

Moxifloxacin has shown excellent efficacy in Europe[23],[32]

, but high rates of quinolone resistance have been observed in the Asia-Pacific area, where moxifloxacin use is greater (see Figure 1). Therefore, to reduce the risk of quinolone-resistant M. genitalium developing, moxifloxacin should not be used first-line in M. genitalium urethritis unless there is known or suspected macrolide resistance.

Alternative regimens

Following macrolide and quinolone failure, therapeutic options for M. genitalium are limited.

Pristinamycin, a streptogramin antimicrobial that has been used to treat Gram-positive organisms in osteo-articular infections, has been used successfully for the treatment of macrolide- and quinolone-resistant M. genitalium infection. However, the drug is expensive, needs to be given four times per day and is not easy to access in the UK[33]

.

For other alternative regimens, see the 2018 BASHH guidelines and seek expert help[1]

.

Side effects and contraindications

Doxycycline, azithromycin and moxifloxacin can cause gastrointestinal side effects, most commonly nausea. However, the side effects from azithromycin are more common in patients taking doses higher than 1g. Caution should be taken when prescribing either azithromycin or moxifloxacin to patients who are already taking medicines that prolong the QT interval (e.g. some anti-arrhythmics, certain antihistamines). Patients should stop treatment with quinolones if they experience side effects relating to muscles, tendons, bones or the nervous system.

Hepatotoxicity is very rare. The only absolute contraindication to moxifloxacin is hypersensitivity to quinolones. In November 2018, a European Medicines Agency alert was issued advising that quinolone use be restricted. Subsequently the status of these drugs in many guidelines has been downgraded[34]

. However, given the severely limited viable treatment options for M. genitalium, moxifloxacin remains important and close attention should be paid to the development of any toxicity in patients.

Pregnancy

There is a paucity of data around pregnancy outcomes with M. genitalium, but it has been associated with a small increased risk of preterm delivery and spontaneous abortion[35]

.

Azithromycin use during pregnancy, even at 500mg orally once daily for two days, is unlikely to increase the risk of birth defects or adverse pregnancy outcomes[36]

.

For pregnant women who have a macrolide-resistant infection, treatment options are limited. The use of moxifloxacin is contraindicated and there are no data regarding the use of pristinamycin in pregnancy. An informed discussion should take place to explain to the patient the risks associated with the use of these medicines in pregnancy, the risks of adverse outcomes associated with M. genitalium infection and, where possible, that treatment should be delayed until after pregnancy.

Follow-up

All patients receiving treatment for M. genitalium infection should have a test of cure five weeks (and no earlier than three weeks) after the start of treatment[37]

. This is vital to ensure that treatment has been successful at eradicating M. genitalium. It is currently unclear whether symptomatic resolution correlates with microbiological cure and, therefore, symptoms cannot be reliably used as an indicator of resolved infection. There have been cases of men receiving treatment for NGU becoming clinically asymptomatic, and subsequently testing positive for persistent M. genitalium

[38],[39]

. There is also an association with persistent M. genitalium infection and antimicrobial resistance[38],[39]

.

Role of the pharmacist

Pharmacists are ideally placed to help reduce the risk of transmission of M. genitalium and the development of antimicrobial resistance. They can:

- Be aware that M. genitalium is a recognised and treatable cause of NGU and PID;

- Explain M. genitalium infection to patients, with particular emphasis on the long-term implications for their health and that of their partner(s);

- Promote consistent condom or femidom use;

- Advise patients to contact their sexual partners for testing;

- Signpost patients to a sexual health or genitourinary medicine clinic;

- Encourage regular STI testing for those at risk;

- Promote the practice to not use azithromycin 1g as empirical treatment for STIs and non-specific genital infections to colleagues;

- Promote antimicrobial stewardship.

The two case studies in the Box give examples of how to manage patients presenting with M. genitalium infection.

Box: Case studies

Case 1

A 21-year-old heterosexual woman presented to a sexual health clinic complaining of abdominal pain and dyspareunia. Following examination, the patient was diagnosed with pelvic inflammatory disease.

A self-taken vaginal swab was sent for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae testing. She was prescribed ceftriaxone, doxycycline and metronidazole.

Nine days later, the patient tested negative for both Chlamydia and gonorrhoea, but re-presented with persistent symptoms. She reported full adherence to the medicines initially prescribed and provided another vaginal sample, which was tested for Mycoplasma genitalium.

Five days later, the patient sample was reported as positive for M. genitalium. The patient was recalled and a day later, was started on moxifloxacin 400mg orally once daily for 14 days.

At the test of cure (TOC) visit, the patient had become asymptomatic. She reported full adherence to treatment and abstained from sexual contact during this time. The vaginal sample taken at that visit subsequently was found to be negative for M. genitalium.

Learning points: In symptomatic women, M. genitalium infection can present as pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). As per the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV guidelines, this patient was prescribed moxifloxacin, which successfully treated the patient’s infection[1]

.

This case highlights the importance of being aware of M. genitalium as a cause of PID, as well as highlighting that this patient should have been tested for M. genitalium at the initial visit, enabling a more timely diagnosis, fewer unnecessary antibiotics to be prescribed and a shorter clinical journey for the patient.

Case 2

A 30-year-old heterosexual man presented to a sexual health clinic complaining of dysuria and urethral discharge. Examination revealed a clear urethral discharge and microscopy of a urethral specimen showed numerous polymorphonuclear leucocytes, but no gonorrhoea. A first-void urine sample was sent for C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhoeae and M. genitalium via nucleic acid amplification techniques. The patient was prescribed doxycycline 100mg twice daily for seven days[40]

.

A week later, the patient re-presented complaining of symptoms despite reporting full adherence to the course of doxycycline. His test result for M. genitalium was positive, but negative for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae. The patient was given 1g azithromycin orally as a single dose, followed by 500mg given orally once-daily for two days. He was booked in for a TOC 5 weeks later and partner notification was completed.

At the TOC visit, the patient was still symptomatic, but had taken the full course of treatment and abstained from sexual contact during this time. His sample subsequently returned a positive result.

The patient was recalled and prescribed moxifloxacin 400mg orally once a day for ten days. Five weeks later, the patient reported full resolution of symptoms and TOC was negative for M. genitalium.

Learning points: Male urethritis is a common presentation of M. genitalium and this patient has non-chlamydial, non-gonococcal urethritis — the most common cause of which is M. genitalium.

This patient experienced treatment failure of M. genitalium most likely because he had a macrolide-resistant strain of the organism and, for this reason, azithromycin therapy should not be repeated. Although this patient’s infection was successfully treated, the patient attended the clinic five times before achieving a microbiological cure. His clinical journey could have been reduced if the initial sample was also sent for detection of macrolide-resistance mutations.

References

[1] Soni S, Horner PJ, Rayment M et al. 2018 British Association for Sexual Health and HIV national guideline for the management of infection with Mycoplasma genitalium. 2018. Available at: https://www.bashhguidelines.org/media/1198/mg-2018.pdf (accessed August 2019)

[2] McGowin CL, Ma L, Martin DH & Pyles RB. Mycoplasma genitalium-encoded MG309 activates NF-kappaB via Toll-like receptors 2 and 6 to elicit proinflammatory cytokine secretion from human genital epithelial cells. Infect Immun 2009;77(3):1175–1181. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00845-08

[3] Sonnenberg P, Ison CA, Clifton S et al. Epidemiology of Mycoplasma genitalium in British men and women aged 16–44 years: evidence from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). Int J Epidemiol 2015;44(6):1982–1994. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv194

[4] Soni S, Alexander S, Verlander N et al. The prevalence of urethral and rectal Mycoplasma genitalium and its associations in men who have sex with men attending a genitourinary medicine clinic. Sex Transm Infect 2010;86(1):21–24. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.038190

[5] Bradshaw CS, Fairley CK, Lister NA et al. Mycoplasma genitalium in men who have sex with men at male-only saunas. Sex Transm Infect 2009;85(6):432–435. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.035535

[6] Taylor-Robinson D & Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium: from chrysalis to multicolored butterfly. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011;24(3):498–514. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00006-11

[7] Horner PJ & Martin DH. Mycoplasma genitalium infection in men. J Infect Dis 2017;216(Suppl 2):S396–S405. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix145

[8] Wiesenfeld HC & Manhart LE. Mycoplasma genitalium in women: current knowledge and research priorities for this recently emerged pathogen. J Infect Dis 2017;216(Suppl 2):S389–S395. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix198

[9] Lis R, Rowhani-Rahbar A & Manhart LE. Mycoplasma genitalium infection and female reproductive tract disease: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61(3):418–426. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ312

[10] Golden MR, Workowski KA & Bolan G. Developing a public health response to Mycoplasma genitalium. J Infect Dis 2017;216(Suppl 2):S420–S426. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix200

[11] Gesink DC, Mulvad G, Montgomery-Andersen R et al. Mycoplasma genitalium presence, resistance and epidemiology in Greenland. Int J Circumpolar Health 2012; 71(1):1–8. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v71i0.18203

[12] Björnelius E, Magnusson C & Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium macrolide resistance in Stockholm, Sweden. Sex Transm Infect 2017;93(3):167–168. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2016-052688

[13] Shipitsyna E, Rumyantseva T, Golparian D et al. Prevalence of macrolide and fluoroquinolone resistance-mediating mutations in Mycoplasma genitalium in five cities in Russia and Estonia. PLoS One 2017;12(4):e0175763. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175763

[14] Hokynar K, Hiltunen-Back E, Mannonen L & Puolakkainen M. Prevalence of Mycoplasma genitalium and mutations associated with macrolide and fluoroquinolone resistance in Finland. Int J STD AIDS 2018;29(9):904–907. doi: 10.1177/0956462418 764482

[15] Salado-Rasmussen K & Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium testing pattern and macrolide resistance: a Danish nationwide retrospective survey. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59(1):24–30. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu217

[16] Gratrix J, Plitt S, Turnbull L et al. Prevalence and antibiotic resistance of Mycoplasma genitalium among STI clinic attendees in Western Canada: a cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open 2017;7(7):e016300. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016300

[17] Nijhuis RH, Severs TT, Van der Vegt DS et al. High levels of macrolide resistance-associated mutations in Mycoplasma genitalium warrant antibiotic susceptibility-guided treatment. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015;70(9):2515–2518. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv136

[18] Pitt R, Fifer H, Woodford N & Alexander S. Detection of markers predictive of macrolide and fluoroquinolone resistance in Mycoplasma genitalium from patients attending sexual health services in England. Sex Transm Infect 2018;94(1):9–13. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2017-053164

[19] Hamasuna R, Le PT, Kutsuna S et al. Mutations in ParC and GyrA of moxifloxacin-resistant and susceptible Mycoplasma genitalium strains. PLoS One 2018;13(6):e0198355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198355

[20] Getman D, Jiang A, O’Donnell M & Cohen S. Mycoplasma genitalium prevalence, coinfection, and macrolide antibiotic resistance frequency in a multicenter clinical study cohort in the United States. J Clin Microbiol 2016 Sep;54(9):2278–2283. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01053-16

[21] Le Roy C, Hénin N, Pereyre S & Bébéar C. Fluoroquinolone-resistant Mycoplasma genitalium, southwestern France. Emerg Infect Dis 2016;22(9):1677–1679. doi: 10.3201/eid2209.160446

[22] Barberá MJ, Fernández-Huerta M, Jensen JS et al. Mycoplasma genitalium macrolide and fluoroquinolone resistance: prevalence and risk factors among a 2013–2014 cohort of patients in Barcelona, Spain. Sex Transm Dis 2017;44(8):457–462. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000631

[23] Read TRH, Fairley CK, Murray GL et al. Outcomes of resistance-guided sequential treatment of Mycoplasma genitalium infections: a prospective evaluation. Clin Infect Dis 2019;68(4):554–560. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy477

[24] Murray GL, Bradshaw CS, Bissessor M et al. Increasing macrolide and fluoroquinolone resistance in Mycoplasma genitalium. Emerg Infect Dis 2017;23(5):809–812. doi: 10.3201/eid2305.161745

[25] Basu I, Roberts SA, Bower JE et al. High macrolide resistance in Mycoplasma genitalium strains causing infection in Auckland, New Zealand. J Clin Microbiol 2017;55(7):2280–2282. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00370-17

[26] Anderson T, Coughlan E & Werno A. Mycoplasma genitalium macrolide and fluoroquinolone resistance detection and clinical implications in a selected cohort in New Zealand. J Clin Microbiol 2017;55(11):3242–3248. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01087-17

[27] Pond MJ, Nori AV, Witney AA et al. High prevalence of antibiotic-resistant Mycoplasma genitalium in nongonococcal urethritis: the need for routine testing and the inadequacy of current treatment options. Clin Infect Dis 2014;58(5):631–637. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit752

[28] Lau A, Bradshaw CS, Lewis D et al. The efficacy of azithromycin for the treatment of genital Mycoplasma genitalium: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61(9):1389–1399. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ644

[29] Bradshaw CS, Jensen JS, Tabrizi SN et al. Azithromycin failure in Mycoplasma genitalium urethritis. Emerg Infect Dis 2006;12(7):1149–1152. doi: 10.3201/eid1207.051558

[30] Jensen JS, Bradshaw CS, Tabrizi SN et al. Azithromycin treatment failure in Mycoplasma genitalium -positive patients with nongonococcal urethritis is associated with induced macrolide resistance. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47(12):1546–1553. doi: 10.1086/593188

[31] Li Y, Le WJ, Li S et al. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of moxifloxacin in treating Mycoplasma genitalium infection. Int J STD AIDS 2017;28(11):1106–1114. doi: 10.1177/0956462416688562

[32] Anagrius C, Loré B & Jensen JS. Treatment of Mycoplasma genitalium. Observations from a Swedish STD Clinic. PLoS One 2013;8(4):e61481. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061481

[33] Bradshaw CS, Twin J, Bissessor M et al. The efficacy of pristinamycin for Mycoplasma genitalium – an increasing multidrug resistant pathogen. 2015;91:A37. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2015-052270.109

[34] European Medicines Agency. Quinolone- and fluoroquinolone-containing medicinal products. 2018. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/referrals/quinolone-fluoroquinolone-containing-medicinal-products (accessed August 2019)

[35] Padberg S, Wacker E, Meister R et al. Observational cohort study of pregnancy outcome after first-trimester exposure to fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014;58(8):4392–4398. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02413-14

[36] Bar-Oz B, Weber-Schoendorfer C, Berlin M et al. The outcomes of pregnancy in women exposed to the new macrolides in the first trimester. Drug Saf 2012;35(7):589–98. doi: 10.2165/11630920-000000000-00000

[37] Falk L, Enger M & Jensen JS. Time to eradication of Mycoplasma genitalium after antibiotic treatment in men and women. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015;70(11):3134–3140. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv246

[38] Ito S, Shimada Y, Yamaguchi Y et al. Selection of Mycoplasma genitalium strains harbouring macrolide resistance-associated 23S rRNA mutations by treatment with a single 1 g dose of azithromycin. Sex Transm Infect 2011;87(5):412–414. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050035

[39] Manhart LE, Gillespie CW, Lowens MS et al. Standard treatment regimens for nongonococcal urethritis have similar but declining cure rates: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect 2013;56(7):934–942. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis1022

[40] Horner P, Blee K, O’Mahony C; British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. 2015 UK National Guideline on the management of non-gonococcal urethritis. 2015. Available at: https://www.bashhguidelines.org/media/1051/ngu-2015.pdf (accessed August 2019)