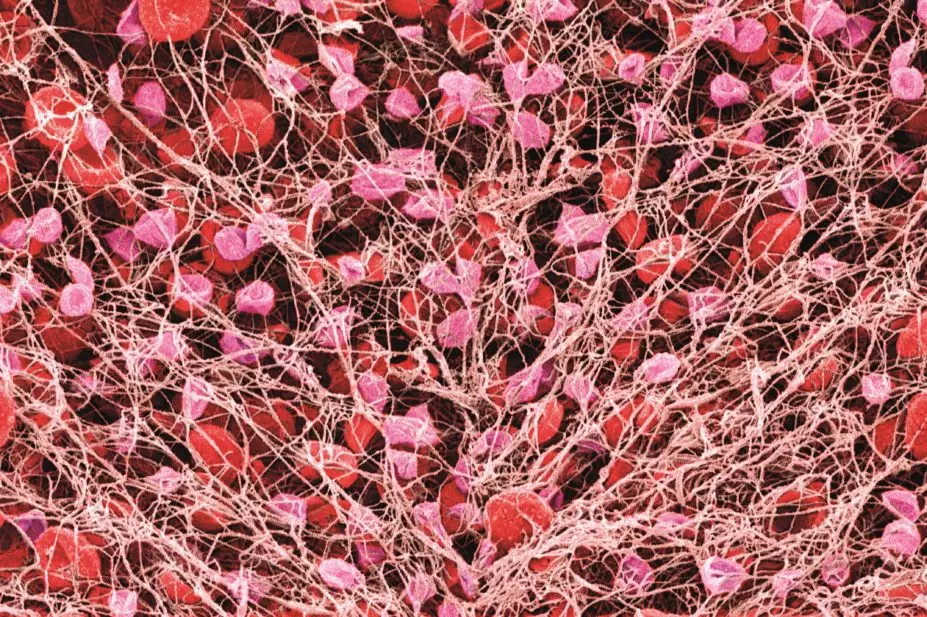

Susumu Nishinaga / Science Photo Library

People using oral blood thinning therapy such as warfarin can successfully monitor and manage their own international normalised ratio (INR) using commercially available devices, research shows.

An impressive 90% of 296 patients were still self-monitoring 12 months after buying a device, with eight adverse events reported by GPs. These included two deaths, four bleeding events, a thrombosis and a transient ischaemic attack.

Two studies published in the British Journal of General Practice were led by Alison Ward from the Nuffield department of primary care health sciences at the University of Oxford, and based on interviews and assessments of individuals who purchased a point-of-care INR monitor (Roche’s CoaguChek®) in England over a 12-month period.

The first was a prospective study[1]

looking at the effectiveness of anticoagulant monitoring in the community, while the second paper[2]

looked at the patients’ experiences of self-monitoring.

The number of patients purchasing the devices, 299 in total, is surprisingly low, notes an editorial accompanying the research. This could be explained in part by the cost; the device involves an initial outlay of around £300 plus ongoing costs for test strips, needles and batteries. The high cost would also help explain the demographics of the cohort, which mainly comprised university-educated, professional people.

In all, 45% of the patients self-monitored their INR but received assistance with dose adjustment, and 40% both self-monitored and adjusted their own medication. Nearly all participants said they had used the information book or DVD that came with the monitor, but only 46% had received in-person training, lasting for a median of just 35 minutes. The majority of this training took place in an outpatient hospital setting (62.5%), followed by primary care (36.8%).

Nevertheless, the mean time in the therapeutic range (TTR) — defined as the proportion of INR measurements within the patient’s target range, indicating optimal anticoagulation control — was 75.3%, with older age being associated with a greater TTR.

“[I]t should be noted that participants in this study were highly educated so caution should be taken with regard to generalising the findings to the broader population,” the authors remark.

In qualitative interviews with 26 of the patients, users described their experience of self-monitoring as mostly positive, although some said it was difficult or stressful at first. Patients welcomed the opportunity for training but noted that effort was required to conduct self-monitoring tests and to interpret and act on the results.

Concluding the descriptive paper, Ward and her colleagues write: “Better training and robust support systems would have helped address problems and will, therefore, be important if self-monitoring becomes more widely available.”

Maureen Talbot, senior cardiac nurse at the British Heart Foundation (BHF), said: “The BHF supports the principle of self-testing when clinically appropriate and if patients wish to adopt this approach. This practice is not widespread in the UK due to cost.

“These studies demonstrate the importance of appropriate training and support for those who choose to self-monitor the effect of warfarin on their blood clotting levels, to ensure success. If a person is self-testing at present and finding it a challenge they should seek support from their healthcare professional.”

Based on their research, the authors have developed a set of recommendations to improve training and support and other aspects of INR self-monitoring.

References

[1] Ward A, Tompson A, Fitzmaurice D, et al. Cohort study of Anticoagulation Self-Monitoring (CASM): a prospective study of its effectiveness in the community. Br J Gen Pract. 2015;65(636):e428–437. doi:10.3399/bjgp15X685633.

[2] Tompson A, Heneghan C, Fitzmaurice D, et al. Supporting patients to self-monitor their oral anticoagulation therapy: recommendations based on a qualitative study of patients’ experiences. Br J Gen Pract. 2015;65(636):e438–446. doi: 10.3399/bjgp15X685645.