Key points:

- Acute viral bronchitis is a benign and self-limiting illness with no specific therapy;

- ‘Red flag’ symptoms should be identified during the consultation and appropriate action taken;

- If symptomatic therapy is required, home remedies or a simple linctus provides benefit through a demulcent effect;

- Additional benefit may be obtained through pharmacotherapy with over-the-counter (OTC) medicines aimed at normalising the cough reflex.

Introduction

Acute cough is the most common presentation of illness in the community. It is responsible for more than 50% of new patient attendance in primary care and is the major source of patient consultation in pharmacy practice[1]

. Since symptomatic therapy is the mainstay of management of this generally benign and self-limiting illness, pharmacists are the main healthcare professionals involved in treatment of the condition[1]

. Because there have been relatively few clinical trials that meet high modern standards, much of the over-the-counter (OTC) therapy currently recommended in the UK is based on custom and traditional practice rather than clinical evidence. This article reviews the diagnosis and therapeutic options available for the treatment of what is perhaps the most common of all ailments[1]

.

Acute cough is the most common reason for a new patient seeking medical advice, accounting for a large proportion of GP appointments and community pharmacy consultations[2],

[3]

. Around one in five people in the UK suffers an acute cough during the winter months[4]

and there are around 2.6 million GP consultations for cough each year[5]

. It is estimated that coughs cost the UK economy about £1bn a year[3]

in lost productivity and healthcare costs.

Acute cough has been arbitrarily defined as being less than three weeks’ duration[4]

and, in otherwise healthy adults, it has an average duration of 14–21 days[6]

. Chronic cough, defined as lasting more than eight weeks, may be a symptom of a chronic respiratory or gastrointestinal disease, but in many cases it is caused by non-acid reflux secondary to oesophageal dysmotility[7]

.

Nearly all cases of acute cough are caused by viral upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs)[3]

; one of the key areas for patients seeking treatment from community pharmacy. According to the ‘Community pharmacy management of minor illness’ report, of the 377 patients recruited for the study (undertaken to look at future delivery of community pharmacy-based minor ailments schemes), 28.9% were seeking treatment for upper respiratory tract problems such as coughs, colds and sore throats[8]

. Only musculoskeletal aches and pains was a more common reason that patients sought treatment for.

Cough tends to start later, but is the longest and often most troublesome symptom of a viral respiratory tract infection[9],

[10]

. Sneezing, runny nose, nasal congestion and headache appear early in the course of the disease; cough generally appears on day two or three, emerges as the most troublesome symptom on days six and seven[9]

, and may persist for up to 25 days[10]

.

Source selection

No formal literature search was conducted. An extensive cough-related database has been developed and compiled by the author in EndNote and relevant articles were obtained in their original PDFs. Where necessary, further references were added from PubMed. Further information can be obtained from the author by request.

Outdated classification

The way that community pharmacy (and indeed the NHS authorities and the medical profession in general) manage cough is in urgent need of review. Pharmacists have long been trained to ask patients about whether their cough is ‘wet’, ‘dry’, ‘chesty’ or ‘tickly’. This approach dates back many decades and probably even longer. The Greek physician Hippocrates (c. 460 BC–c. 370 BC) and then Galen (c. 130 AD–c. 210 AD) suggested that illness resulted from an imbalance of the four humours, which included phlegm[11]

. Today, we still prescribe expectorants with very little additional evidence. In more recent times, cough classification was intended to manage conditions such as tuberculosis with considerable bronchorrhea, with emphasis on the importance of ‘coughing up’ phlegm[12]

. The amount of mucus associated with most viral coughs is, in reality, negligible, and in acute URTI there is little, if any, difference between a ‘dry’ cough and one that produces minimal amounts of sputum[13]

.

It has become increasingly recognised that an acute cough consists of just one syndrome caused by viral-induced inflammation and epithelial damage of the upper airways[14],

[15]

. Cough and its associated symptoms, including sore throat and tickle, are all explicable by increased sensitivity, or rather, hypersensitivity of these afferent sensory nerves. This increased sensitivity is of the sensory nerves of the tenth cranial nerve (the vagus) and has been termed ‘cough hypersensitivity syndrome’[14],

[15]

.

Hypersensitivity of the cough reflex occurs during a URTI: the body’s natural cough reflex becomes hypersensitive, causing the urge to cough[14],

[15]

. With a cold, for instance, bouts of coughing can occur as the result of minor environmental changes, such as a drop in temperature or exposure to cigarette smoke, perfumes or aerosols[16]

. This explains why people with acute cough experience coughing when stepping out into the cold. The molecular mechanism for this hypersensitivity has now been identified and resides in hot and cold sensory receptors known as TRP receptors[17]

. The archetypal TRPV1, or capsaicin receptor, is a hot receptor as well as a cough receptor; hence the use of capsaicin in cough-challenge tests[15]

.

Cough reflex hypersensitivity induced by a virus is a fundamental phase of URTI. In evolutionary terms it enables the viruses to spread by droplet transmission[18]

. Indeed, viruses that do not provoke cough may not pass to the next host. A reduction in cough sensitivity will not only help to relieve the symptoms of people suffering from a cough, whether ‘dry’ or ‘chesty’, but it may also inhibit contagion. If we believe ‘coughs and sneezes spread diseases’, it follows that this will inhibit transmission and diminish person-to-person spread[18]

. As all common colds are driven by cough-reflex hypersensitivity, the goal of therapy should be to reduce this hypersensitivity and to normalise the cough reflex.

It is time we recognised that using the old ‘wet/dry’ classification is not the best way to help patients with acute cough symptoms. As such, international experts have recently called for removal of this classification and development of a new pathway that will enable healthcare professionals to provide more effective advice to individuals suffering from acute cough[19]

.

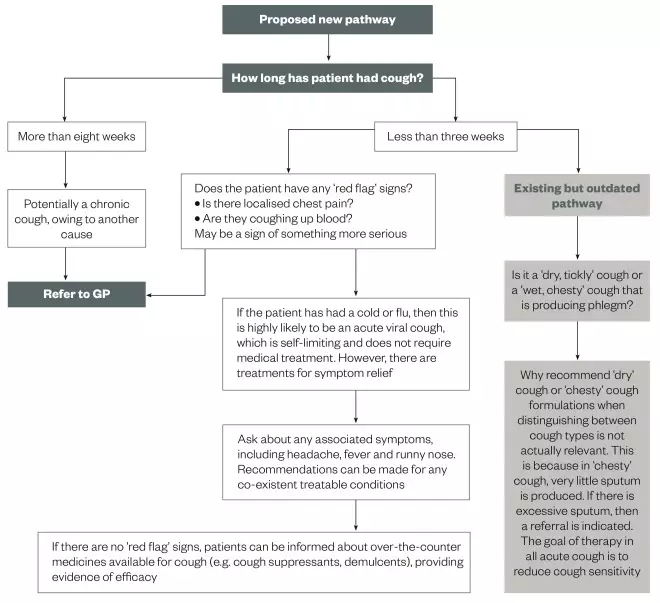

New pathway

A new proposed treatment pathway for cough is outlined in Figure 1. This should be further developed and refined with input and help from community pharmacists, as it will need to address key questions and points to allow pharmacists, technicians and medicines counter assistants to provide patients seeking advice for cough with appropriate advice. These include:

- How long have you had the cough?

- If it is less than three weeks, then it is highly likely to be an acute cough related to a respiratory tract infection;

- Although disruptive, an acute cough associated with a URTI is self-limiting and rarely needs significant medical intervention, particularly the use of antibiotics. Individuals can be reassured and advised of a range of options for symptom relief;

- Are there any associated symptoms, such as headache, fever or runny nose?

- If so, pharmacists and pharmacy assistants have the opportunity to adjust their recommendations according to any co-existent treatable symptoms;

- Having addressed these points, pharmacists and pharmacy assistants then have an opportunity to advise on OTC drugs currently available for cough, providing evidence of efficacy where it exists;

- The consultation should include a discussion about other symptoms. Crucially, are there any ‘red flag’ symptoms, such as localised chest pain or coughing up blood, which potentially indicate more serious pathology? For instance, pleuritic chest pain (which may be described as pain on inspiration localised to the chest, worsening when coughing, sneezing or moving around) may be a sign of pneumonia, and a consultation with the doctor leading to an x-ray should be sought. Any such ‘red flag’ signs, or a cough persisting for longer than eight weeks (i.e. a chronic cough), require at least a GP referral.

Note that the proposed treatment pathway (see Figure 1) only focuses on the treatment of adults and children aged over 12 years. Younger patients (aged 12 years and under) are not included in this new pathway. Further information relating to their management should be obtained from the British Thoracic Society guidelines[20]

.

Figure 1: Assessment of acute cough in adults and children 12+ years in pharmacy

A suggested starting point for a new pathway for discussion with pharmacists for full development

Lack of evidence for OTC preparations

Different types of products have traditionally been recommended for different types of cough (‘dry’, ‘tickly’ or ‘chesty’). Expectorants have been used for ‘chesty’ (‘productive’) coughs while suppressants are routinely recommended for ‘dry’ (‘non-productive’) coughs[12]

.

However, it is the opinion of this author that distinguishing between ‘dry’ and ‘chesty’ cough has more to do with brand diversification than rational antitussive pharmacology. The vast range of OTC cough preparations now available is likely to cause confusion among patients coming into the pharmacy, who are clearly looking for symptom relief, but often do not know which formulation would provide the most benefit.

Cough medicines are big business, but much of the evidence used to support claims of effectiveness comes from clinical studies that were conducted decades ago, against a backdrop of an outdated ‘wet’ or ‘dry’ cough classification[21]

: this leads to understandable doubt as to their efficacy. Despite major expenditure on medicines for acute cough (amounting to nearly £100m in the UK in 2014[22]

) there is a worrying lack of good modern evidence to support their effectiveness. Until recently, no new drug had been licensed for acute cough for more than 30 years, which explains why the research supporting licensed indications for current OTC medicines is poor by current standards.

Studies often used subjective measures; sometimes simply asking patients if they thought their cough had improved, and many long-established preparations obtained their license on this basis[1]

. However, claims made of antitussive activity that are based solely on subjective criteria do not provide enough evidence of efficacy; a view supported by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the body responsible for evaluating the safety and efficacy of medicines in the United States[1]

.

The studies supporting current OTC medications generally used too few patients[23],

[24],

[25]

. Perhaps more importantly, many studies were conducted in an inappropriate patient population and in patients with a mixture of different diseases, from chronic bronchitis to lung cancer[1],

[23],

[25]

. In the current era of evidence-based medicine, antitussive claims for many traditional antitussive preparations do not stand up to scrutiny; hence the negative perceptions of OTC cough remedies reported in the media and by regulators[23]

. There may be some efficacy in our current pharmacopoeia, but this has not been proven to modern standards, and since the products are off patent, there is no financial advantage in demonstrating efficacy because any proven claims will also be adopted by competitors.

Objective measures of cough

Key objective measures designed to assess cough more rigorously include cough challenge and cough counting. Cough challenge was introduced more than 50 years ago as an accurate tool for assessing cough reflex. The inhalation cough challenge facilitates the quantification of cough and the assessment of antitussive effects of specific therapies. To do this, tussive agents such as citric acid or capsaicin (the pungent extract of the Capsicum chili pepper genus) are delivered as nebulised solutions to determine cough reflex sensitivity. The effect of a drug on their cough reflex sensitivity is then compared with that of placebo. Two methods are used: single dose (administering one concentration of the tussive agent) and dose-response using incremental dosing[26]

.

The cough challenge methodology is frequently used in the development of new therapies and is recommended by the FDA as part of the submission portfolio[1]

, but the problem is that it does not always correlate with subjective measures. For instance, while morphine has been shown to be significantly effective in suppressing chronic cough in some patients, it does not appear to alter cough reflex sensitivity[1]

. By contrast, the most commonly prescribed OTC drug for cough, dextromethorphan, has been clearly demonstrated to suppress cough reflex hypersensitivity by cough challenge experiments[27]

. Thus, the methodology used in an individual experiment may determine whether there is a positive or negative outcome.

Researchers have attempted to quantify the amount of coughing per unit time by one method or another for more than 50 years[1]

. The process can be done aurally, which is highly laborious but has demonstrated efficacy with one agent: dextromethorphan[28],

[29]

. The first cough-monitoring systems developed were basic non-ambulatory mains-supplied tape recorders with microphones, but now ambulatory systems use digital technology to count coughs over a 24-hour period[30]

. As yet, these have been of limited use in OTC research because so few current medications have been studied. Recent experience of newly developed antitussive medications, such as AF 219, have shown that cough counting is highly accurate and confirm that a balance of subjective and objective measures is needed to evaluate antitussive activity and provide a complete picture of efficacy[31]

.

Lack of validated data

Despite the attempt to introduce accurate measures, and taking into account existing research, it remains difficult to evaluate overall effectiveness of OTC medicines. Indeed, this is the conclusion of a major Cochrane review that analysed 29 trials involving 4,835 patients[23]

. The review identified a broad range of studies, undertaken over five decades, of different types of preparations, used at different dosages in children and adults. The randomised controlled trials (RCTs) compared OTC cough preparations with placebo in individuals suffering from acute cough in community settings and considered all cough outcomes, including severity, frequency and amount of sputum. The review also considered different measurement methods, such as cough counting, patient questionnaires and physician assessment[23]

.

The largest amount of data reviewed was for antitussives (six trials involving 1,526 adults and four trials involving 327 children), but the researchers also examined the evidence for expectorants, mucolytics, antihistamine-decongestant combinations, antihistamines and honey (which was shown to improve symptoms among children)[23]

. Most studies (21 of 29) reported on adverse events but none was serious[23]

.

As Smith et al. point out[23]

; their finding that there is no good evidence for or against the effectiveness of OTC medications in acute cough confirms findings from two previous studies[24],

[25]

. They nonetheless suggest that the results of their systematic review need to be interpreted with caution as the number of trials in each group was small and it was difficult to compare the trials directly, given the significant differences between the studies[23]

. Not surprisingly, the authors found that most studies failed to provide quantitative data on cough. The authors concluded that the “overall quality of trials is dubious and there are conflicting results between trials in each medication group”[23]

. The opinion of this author is that this document is an illustration of the problem of performing this sort of analysis on such a diffuse and disparate subject. What we need are fresh, correctly performed studies

Antitussive drug efficacy

In an attempt to promote rational prescribing, this author, along with colleagues has reviewed the evidence for frequently used treatments in acute cough[1]

. They examined three aspects of drug efficacy on acute cough: the effect of the cough reflex using cough challenge; and objective (cough recording) and subjective (for example, symptom scores or specific quality-of-life tools) clinical outcomes. Also see ‘Table 1. RCT-proven efficacy of antitussives by three different cough measurement methods in acute bronchitis’.

| Subjective clinical symptoms | Cough challenge test | Objective cough recording | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Codeine | – | – | – | No convincing evidence of efficacy |

| Dextromethorphan | + | ++ | + | Well characterised in objective studies |

| Diphenhydramine | ++ | ++ | – | Broad clinical use |

| Menthol | – | + | – | Vapour antitussive via TRPM8 receptor |

Dextromethorphan

Only dextromethorphan has been demonstrated to significantly suppress acute cough using objective measures. In six studies, reproducible cough suppressant effects were demonstrated after a single 30mg dose of dextromethorphan compared with placebo, using objective measures of cough counts, latency and total effort[28]

.

Dextromethorphan was also revealed to have a relatively slow onset of action, peaking after around two hours. The slow penetration, through the blood–brain barrier and consequent nervous system retention, may give the drug prolonged antitussive activity, still being significantly better than placebo after 24 hours[32]

.

Codeine

Although codeine is widely used and is often considered the archetypal antitussive, there is very little clinical evidence supporting significant antitussive action for orally administered codeine. Some studies have reported a small but significant effect[21]

while others report no effect on cough challenge or the sensation of urge to cough[21]

.

Both overdosing and underdosing are concerns with codeine because it is not possible to predict the degree of opiate effects in anyone who has not previously used the drug. Codeine is bio-activated by CYP2D6 into morphine, which then undergoes further glucuronidation[33]

. Rates of metabolism can vary dramatically owing to marked genetic differences in cytochrome P450-dependent monooxygenase activity. Some patients are fast metabolisers, converting the most of the codeine to morphine at first pass through the liver. However, in slow metabolisers, very little of the drug is converted, which makes efficacy an issue for slow metabolisers and toxicity a potential problem for fast metabolisers[31]

. Children who are fast metabolisers have been observed to have dangerous levels of sedation and suppression of respiration[34]

, and this author believes this is not just a problem in the young, and would argue that the dangers of codeine far outweigh its very limited evidence of efficacy in clinical trials.

Butamirate

These preparations are widely used in Europe as OTC antitussives, but previous studies demonstrating efficacy were not placebo-controlled[35]

.

A recent placebo-controlled, six-way randomised, cross-over study did not demonstrate any greater cough reflex suppression than placebo[36]

. None of the 34 subjects who completed the study experienced any significant efficacy from any of the four doses. The dextromethorphan control, however, was superior to placebo. Butamirate is an example of a drug that has been licensed on the basis of studies in inappropriate disease categories that had no objective measures of efficacy. Butamirate is not licensed in the UK.

Ambroxol

As an active metabolite of bromhexine, ambroxol is the most popular drug on the German OTC cough market. In 2015, it accounted for 24% of the expectorant market share with an additional 1.7% for bromhexine (IMS OTC 2015 report)[37]

. Only one randomised, double-blind, controlled study has been published to examine the effectiveness of ambroxol as a treatment for acute cough in adults[38]

. This one RCT proves its symptomatic efficacy versus placebo for cough. This drug has been included as an example of the misclassification of potentially effective antitussives. Although not available in the UK, in Germany it is marketed as an expectorant even though current evidence suggests that it is effective in decreasing cough hypersensitivity rather than having any ‘expectorant’ effect. Indeed, to the best of my knowledge, there is no evidence that any expectorant aids expectoration.

Pholcodine and guaifenesin are also widely used as expectorants.

Menthol

Produced by the plant Mentha arvensis, menthol has become a stock ingredient of many OTC preparations, although few clinical studies have been performed.

A small study showed that menthol vapour resulted in a decrease in capsaicin-induced cough[39]

. Another study demonstrated that menthol via the inhaled route was highly effective in suppressing cough challenge with citric acid[40]

. Recent research has shown that menthol vapour may act largely by providing a cooling sensation in the nose[16],

[41]

. We now know that menthol is not just a flavouring, it also activates a specific TRP receptor, the cold receptor TRPM8, which responds to a number of stimuli, including cold. When these receptors are activated they trigger depolarisation of sensory nerves[16]

. In the case of TRPM8, this appears to initiate an antitussive effect along with mild anaesthesia and a cooling sensation[42]

.

At last, our understanding of the pharmacology appears to be catching up with traditional thinking for this valuable agent.

Diphenhydramine, ammonium chloride and demulcents

Diphenhydramine is a first generation H1 antihistamine that has been approved in some countries (including the UK and the United States) as an OTC antitussive[1]

. It has been reported to reduce heightened cough reflex sensitivity in subjects with URTI-associated cough[43]

.

Ammonium chloride is an acid-forming salt that is thought to exert an ‘expectorant’ effect by loosening sputum[43]

. It is usually used in combination with other expectorants and cough mixtures.

Demulcents are thought to reduce cough and cold symptoms by an action hypothesised to be a soothing effect on the mucus membrane[44]

. At the 5th American Cough Conference held in Washington in 2015, the demulcent effect was extensively discussed, but while most of the delegates agreed that clinical practice suggested efficacy, there is no trial that unequivocally demonstrates such an effect, and the term demulcent does not have a precise clinical definition. However, almost all OTC antitussive medications come in the form of syrups.

Emerging evidence: the ROCOCO trial

Unicough, a pharmacy-only P medicine (CS1002) designed to treat all common coughs by tackling cough-reflex hypersensitivity, was the first antitussive to be studied in a rigorous ‘modern’ setting[45]

. This formulation contains diphenhydramine, ammonium chloride and levomenthol in a cocoa-flavoured demulcent. Unlike older cough medicines, the formulation has been evaluated in a real-world, randomised, controlled, multi-centre study[45]

. The ROCOCO study is the largest clinical trial of a cough medicine conducted in the UK, and used an active comparator (simple linctus), while using validated end points in the correct population.

The multi-centre study of 163 patients recruited from 14 pharmacies and GP surgeries, found clear superiority for Unicough over a simple linctus — a widely used and often recommended remedy[44]

. The Unicough group had a statistically significant reduction in sleep disruption throughout the eight-day trial, and there was a statistically significant improvement in cough frequency on days three, four and five[45]

.

Perhaps more importantly, 29.3% of patients in the Unicough group achieved cough resolution by day four, compared with just 17.3% of those taking the linctus[45]

. While 24.4% of those receiving Unicough were able to stop taking their medication by day four because their cough had got better, only 10.7% of the linctus group were able to stop taking their medication at this stage[45]

. However, this also highlights the challenges of investigating a condition that can improve rapidly owing to natural recovery.

ROCOCO is an exemplar of a real-world study design of an OTC antitussive. It was randomised and controlled with an appropriate placebo, and used extensively validated end points as a measure of efficacy. It was also performed in the appropriate study population; those with the common cough in a real-world setting, in mostly community pharmacies. It is the first study to challenge the idea that different types of cough require different medicines; offering evidence that the traditional method of classifying common coughs as ‘wet’ or ‘dry’ is outdated and unhelpful.

Development of a formulation such as Unicough, which is designed to have an impact on all types of cough, also symbolises progress. Unicough is the first pharmacy-only cough medicine to be licensed in 30 years[12]

; it is clinically proven and is the only pharmacy-only medicine authorised by the Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Agency, which regulates medicines and medical devices in the UK, for ‘relief of common coughs’[12],

[46]

.

Indeed, it is the opinion of this author that this approach is the way forward for the treatment of common cough, as it focuses on controlling cough hypersensitivity, which is key to our understanding of how to reduce the urge to cough.

For many years, the lack of quality data associated with most current OTC cough medication has held us back and encouraged healthcare professionals to cling on to the unhelpful and out-dated ‘wet’ and ‘dry’ cough classifications. This reflects the way OTC cough medicines are marketed, rather than relying on any proven efficacy based on clinical evidence. In this author’s view, the key assessment points for cough are duration (to establish whether it is acute or chronic) and associated symptoms (to ascertain whether a GP referral and/or further assessment are required). That is why it is important for pharmacists to routinely ask patients about any ‘red flag’ signs.

Conclusion

The ‘wet’ or ’dry’ classification for cough has been ingrained in our approach to managing cough for far too long. There is one trigger for common cough: increased sensitivity of the nerve endings in the throat[14],

[15]

.

It is clearly time to abandon the ‘wet’ and ‘dry’ classification of cough, recently described by international experts as ‘an anachronism from the era of rampant tuberculosis’[19]

. These arbitrary categories are based on what was once best practice for the treatment of tuberculosis and chronic bronchitis, and have no place in the modern-day real world where there is no danger of the, previously fit, patient with acute cough drowning in their own phlegm.

Acute cough is caused by viral bronchitis for which there is no specific treatment and, although self-limiting, it can cause considerable distress, so it is important to provide the right symptomatic relief, aid cough resolution, and reduce sleep disruption, cough frequency and severity. There is currently a wide range of OTC cough remedies from which to choose, but they are not all supported by proven clinical efficacy and are divided into unhelpful ‘wet’ and ‘dry’ categories. Our treatment advice must be based on normalising the cough reflex.

Our understanding of the cough reflex and the factors leading to cough hypersensitivity has increased considerably over the past decade[19]

but there remain gaps in our knowledge of acute cough therapy. There is a need for a better understanding of the changes in airway sensory nerves and the pathways that underpin the hypertussive state.

Importantly, our improved understanding of the mechanism of cough hypersensitivity brings rational treatment choices a step closer. Now, clear guidelines need to be developed with the regulatory authorities for the validation of any new cough treatments.

The development and testing of new formulations in well-designed RCTs using validated modern methodology demonstrates a clear way forward. This and the new proposed model should help us to re-evaluate the way we think about cough and provide healthcare professionals with the information needed to provide the best evidence-based advice on the treatment of acute cough.

A new model and way of working holds the promise to make assessment of cough easier and, importantly, is evidence-based. Instead of questioning patients whether their cough is ‘wet’ or ‘dry’, the important thing to identify is whether the cough is ‘acute’ or ‘chronic’.

Financial and conflicts of interest disclosure:

The author was senior author of the Rococo study and has consulted for Infirst, the manufacturers of Unicough. The author has received consulting fees from Afferent, Boehringer Ingelheim, Infirst, Merck, Pfizer, and Proctor & Gamble; lecture fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and AstraZeneca; and grant support from Proctor & Gamble.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] Morice A & Kardos P. Comprehensive evidence-based review on European antitussives. BMJ Open Resp Res 2016;3:e000137. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2016-000137

[2] Schappert SM. National ambulatory medical care survey: 1991 summary. Adv Data 1993;230:1–16. PMID: 10166751

[3] Morice AH, McGarvey L & Pavord I on behalf of the British Thoracic Society Cough Guideline Group. Recommendations for the management of cough in adults. Thorax 2006;61 Suppl 1:i1–24. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.065144

[4] Proprietary Association of Great Britain (PAGB). Self Care Forum cough fact sheet. Available at: http://www.selfcareforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/7-Cough.pdf (accessed March 2017)

[5] Proprietary Association of Great Britain (PAGB). Making the case for the self-care of minor ailments, 2009. Available at: http://www.selfcareforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/Minorailmentsresearch09.pdf (accessed March 2017).

[6] Albert RH. Diagnosis and treatment of acute bronchitis. Am Fam Physician 2010;82(11):1345–1350. PMID: 21121518

[7] Kastelik JA, Redington AE, Aziz I et al. Abnormal oesophageal motility in patients with chronic cough. Thorax 2003; 58(8):699–702. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.8.699

[8] Community Pharmacy Management of Minor Illness; MINA Study, Pharmacy Research UK, January 2014. Available at: https://pharmacyresearchuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/MINA-Study-Final-Report.pdf (accessed March 2017)

[9] Witek TJ, Ramsey DL, Carr AN et al. The natural history of community-acquired common colds symptoms assessed over 4 years. Rhinology 2015;53(1):81–88. doi: 10.4193/Rhin14.149

[10] Thompson M, Cohen H, Vodicka T et al. Duration of symptoms of respiratory tract infections in children: systematic review. BMJ 2013;347:f7027. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f7027

[11] Source Book of Medical History, Logan Clendening, Courier Corporation, 1960.

[12] Morice AH. It’s time to change the way we approach coughs in community pharmacy. Clin Pharm 2016;8:3. doi: 10.1211/CP.2016.20200821

[13] Morice AH, Widdicombe J, Dicpinigaitis P et al. Understanding cough. Eur Respir J 2002;19(1):6–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00281002

[14] Morice AH, Millqvist E, Belvisi MG et al. Expert opinion on the cough hypersensitivity syndrome in respiratory medicine. Eur Respir J 2014;44(5):1132–1148. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00218613

[15] Dicpinigaitis PV. Effect of viral upper respiratory tract infection on cough reflex sensitivity. J Thorac Dis 2014;6(s7):S708–S711. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.12.02

[16] McGarvey L, McKeagney P, Polley L et al. Are there clinical features of a sensitized cough reflex? Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2009;22(2):59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2008.11.003

[17] McKerny DD. Chapter 13 TRPM8: The cold and menthol receptor. In: TRP ion channel function in sensory transduction and cellular signaling cascades. Liedtke WB & Heller S eds. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; 2007. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK5238 (accessed March 2017)

[18] Tyrell D & Fielder M. Cold wars: the fight against the common cold. Oxford University Press, 2002.

[19] Morice AH, Kantar A, Dicpinigaitis PV et al. Treating acute cough: wet versus dry – have we got the paradigm wrong? ERJ Open Res 2015;1:00055-2015. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00055-2015

[20] Shields MD, Bush A, Everard ML et al. on behlaf of the British Thoracic Society Cough Guideline Group. BTS guidelines: Recommendations for the assessment and management of cough in children. Thorax 2008; 63 Suppl 3: iii1–iii15. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.077370

[21] PV, Morice AH, Birring SS et al. Antitussive drugs—past, present, and future. Pharmacol Rev 2014;66:468–512. doi: 10.1124/pr.111.005116

[22] Connelly D. Sales of over-the-counter medicines in 2015 by clinical area and top 50 selling brands. Pharm J March 24, 2016. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2016.20200923

[23] Smith SM, Schroeder K & Fahey T. Over-the-counter (OTC) medications for acute cough in children and adults in community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;(11):CD001831. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001831.pub5

[24] Anonymous. Cough medications in children. Drugs Ther Bull 1999;37(3):19–21. doi: 10.1136/dtb.1999.37319

[25] Smith MBH & Feldman W. Over-the-counter cold medications. A critical review of clinical trials between 1950 and 1991. JAMA 1993;269(17):2258–2263. doi: 10.1001/jama.1993.03500170088039

[26] Morice AH, Kastelik JA & Thompson R. Cough challenge in the assessment of cough reflex. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2001;52(4):365–375. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01475.x

[27] Grattan TJ, Marshall AE, Higgins KS et al. The effect of inhaled and oral dextromethorphan on citric acid induced cough in man. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1995;39:261–263. PMID: PMC136500

[28] Pavesi L, Subburaj S & Porter-Shaw K. Application and validation of a computerized cough acquisition system for objective monitoring of acute cough: a meta-analysis. Chest 2001;120(4):1121–1128. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.4.1121

[29] John A. Most common products with dextromethorphan. Livestrong.com. Available at: http://www.livestrong.com/article/199393- most-common-products-with-dextromethorphan/ (accessed March 2017)

[30] Smith JA, Earis JE & Woodcock AA. Establishing a gold standard for manual cough counting: video versus digital audio recordings. Cough 2002:6. doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-2-6

[31] Smith JA, Kitt M, Sher M et al. Profound antitussive response to P2X3 blockade with AF-219 permits correlation of objective measure of cough with improvement in patient reported outcomes. Abstract A2866 2016. Available at: http://www.atsjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2016.193.1_MeetingAbstracts.A2866 (accessed March 2017)

[32] Abdul-Manap R, Wright CE, Gregory A et al. The antitussive effect of dextromethorphan in relation to CYP2D6 activity. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1999;48(3):382–387. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00029.x

[33] Gasche Y, Daali Y, Fathi M et al. Codeine intoxication associated with ultrarapid CYP2D6 metabolism. N Engl J Med 2004;351(27):2827–2831. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa041888

[34] Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: safety review update of codeine use in children; new boxed warning and contraindication on use after tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm339112.htm (accessed March 2017)

[35] Charpin J & Weibel MA. Comparative evaluation of the antitussive activity of butamirate citrate linctus versus clobutinol syrup. Respiration 1990;57:275–279. PMID: 2095610

[36] Faruqi S, Wright C, Thompson R et al. A randomized placebo controlled trial to evaluate the effects of butamirate and dextromethorphan on capsaicin induced cough in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014;78(6):1272–1280. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12458

[37] Morice A & Kardos P. Comprehensive evidence-based review on European anititussives. BMJ Open Respir Res 2016;3(1):e000137. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2016-000137

[38] Matthys H, de Mey C, Carls C et al. Efficacy and tolerability of myrtol standardized in acute bronchitis. A multi-centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled parallel group clinical trial vs. cefuroxime and ambroxol. Arzneimittelforschung 2000;50(8):700–711. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1300276

[39] Wise PM, Breslin PA & Dalton P. Sweet taste and menthol increase cough reflex thresholds. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2012;25(3):236–241. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2012.03.005

[40] Dicpinigaitis PV, Dhar S, Johnson A et al. Inhibition of cough reflex sensitivity by diphenhydramine during acute viral respiratory tract infection. Int J Clin Pharm 2015;37(3):471–474. doi: 10.1007/s11096-015-0081-8

[41] Plevkova J, Kollarik M, Poliacek I et al. The role of trigeminal nasal TRPM8-expressing afferent neurons in the antitussive effects of menthol. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2013;115(2):268–274. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01144.2012

[42] Morice AH, Marshall AE, Higgins KS et al. Effect of inhaled menthol on citric acid induced cough in normal subjects. Thorax 1994;49:1024–1026. Available at: http://thorax.bmj.com/content/49/10/1024.long (accessed March 2017)

[43] Behera D. Textbook of Pulmonary Medicine (2nd edition). Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd. 2010:20.

[44] Eccles R. Mechanisms of the placebo effect of sweet cough syrups. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2006;152:340–348. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2005.10.004

[45] Birring SS, Brew J, Kilbourn A et al. Rococo study: a real-world evaluation of an over-the-counter medicine in acute cough (a multicenter, randomized, controlled study). BMJ Open 2017;7:e014112. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014112

[46] MHRA Public Assessment Report. Unicough 14mg/135mg/1.1mg in 5ml oral solution (diphenhydramine hydrochloride, ammonium chloride, levomenthol). Available at: http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/par/documents/websiteresources/con553668.pdf (accessed March 2017)

You may also be interested in

Pharmacy maternity smoking cessation pilot scheme discontinued owing to low referral numbers

More than 420,000 common ailments service consultations recorded in 2024