Gino Martini

It is “absolutely critical” that any drop in the number of clinical trials evaluations within the UK is resisted as Brexit nears, Gino Martini, chief scientist for the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS), told a parliamentary meeting.

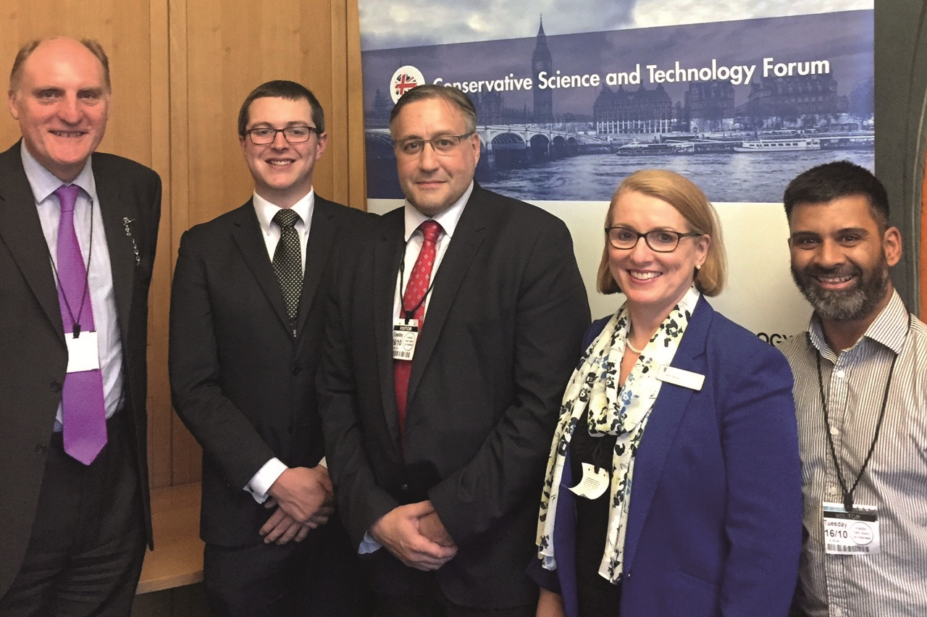

Martini was speaking at ‘What Brexit means for Pharmacy, Pharmaceutical Sciences and Medicines Innovation’ — a meeting hosted by the Conservative Science and Technology Forum and held at Portcullis House on 16 October 2018. The meeting was organised by Sibby Buckle, vice-chair of the English Pharmacy Board. Buckle and Aamer Safdar, member of the RPS English Pharmacy Board, were in attendance, as was health minister Lord O’Shaugnessy.

Drawing on his experience as an academic and pharmaceutical scientist, Martini said that ‘UK PLC’ would benefit from more incentives to attract pharmaceutical and medical investment to the country, including expansion of Seed Enterprise Investment Scheme and Enterprise Investment Scheme schemes which have helped many start-ups get off the ground and develop into small and medium enterprises.

The RPS, Martini told the forum, believes that pharmacists and pharmaceutical scientists will continue to play a prominent role in medicines development after Brexit, as long as certain conditions are met. These include adequate research funding for universities and a continued major role for the UK and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulation Agency (MHRA) in the regulatory oversight of new chemical entities.

Prior to the Brexit vote, the MHRA was undertaking more rapporteur and co-rapporteurships for new products than any other agency under the centralised procedure, Martini said.

“What now for the MHRA, now that the European Medicines Agency will move to Amsterdam? We need to make sure that the MHRA still plays a prominent role with its EU regulator colleagues.”

Pharmacists may have a role to play in ensuring consistent medicines supplies after Brexit, Martini added.

Buckle and Martini proposed that community pharmacies be given the authority to make therapeutic substitutions when dispensing prescriptions — this, they said, would be useful in the event of post-Brexit medicines shortages. “If the supply chains start to ‘creak’, it is not inconceivable that special provisions could be implemented to allow the pharmacist to make informed decisions and substitute an out-of stock-medicine with an alternative generic product or even a therapeutically equivalent product if needs must,” Martini said.

Martini also flagged the risk a ‘hard Brexit’ could pose to the implementation of the Falsified Medicines Directive (FMD) in the UK. In such a scenario, he said, the FMD database — which is stored in the EU — would not be available to UK pharmacists, so they would be unable to check the encoded verification data on medicine packs imported from the EU.

“Will this make the UK look like a weak link in Europe and attract counterfeiters to target the UK?” he asked.

”I know positive steps by the government and MHRA are in play to make sure that the UK has a secure supply chain, and much depends on the outcome of negotiations that are literally still ongoing.”

- This article was updated on 22 November to correct an error in the caption, and to add that Sibby Buckle, vice-chair of the English Pharmacy Board organised the meeting.

You may also be interested in

Long service of members

Membership fees 2022